On a Friday afternoon, the sorting floor of the Daily Bread Food Bank is abuzz with the clattering of cans, the crinkle of plastic packaging, the rip of packing tape, and ABBA’s Dancing Queen piped in from the speakers.

In the bright, clean workspace, a small army of volunteers sifts through large bins of non-perishable donations, collected during a food drive. They discard any food that is unlabelled. Anything more than 10 months past its best before date goes straight into the waste bins, too.

For the past two-and-a-half years, Carolyn Windsor has been driving from her home in St. Catharines to volunteer here at the food bank in Etobicoke at least twice a week. The silver-haired linguistics instructor holds up a tin of soup and peers at the date printed on it. This one is good, she said, but you have to check everything.

“Some people just go into their cupboard and say, ‘Oh, I haven’t used this in four years,’ and they chuck it in,” she said.

Everything that can be used gets sorted into categories. Cartons of tea, hot chocolate powder, and coffee go into boxes labelled “Hot drinks.” Canned corn and beans and instant mashed potatoes are boxed as “Vegetables.”

These boxes are then sent to an adjoining warehouse, stocked with fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as meats and frozen foods kept in a cavernous walk-in freezer and fridge. There, a separate team of volunteers plucks them off the shelves to fill the orders of the Daily Bread’s member agencies across Toronto.

By the end of the day, roughly 150 skids, each piled about five feet high with an assortment of food, will have left the building, destined to feed those in need.

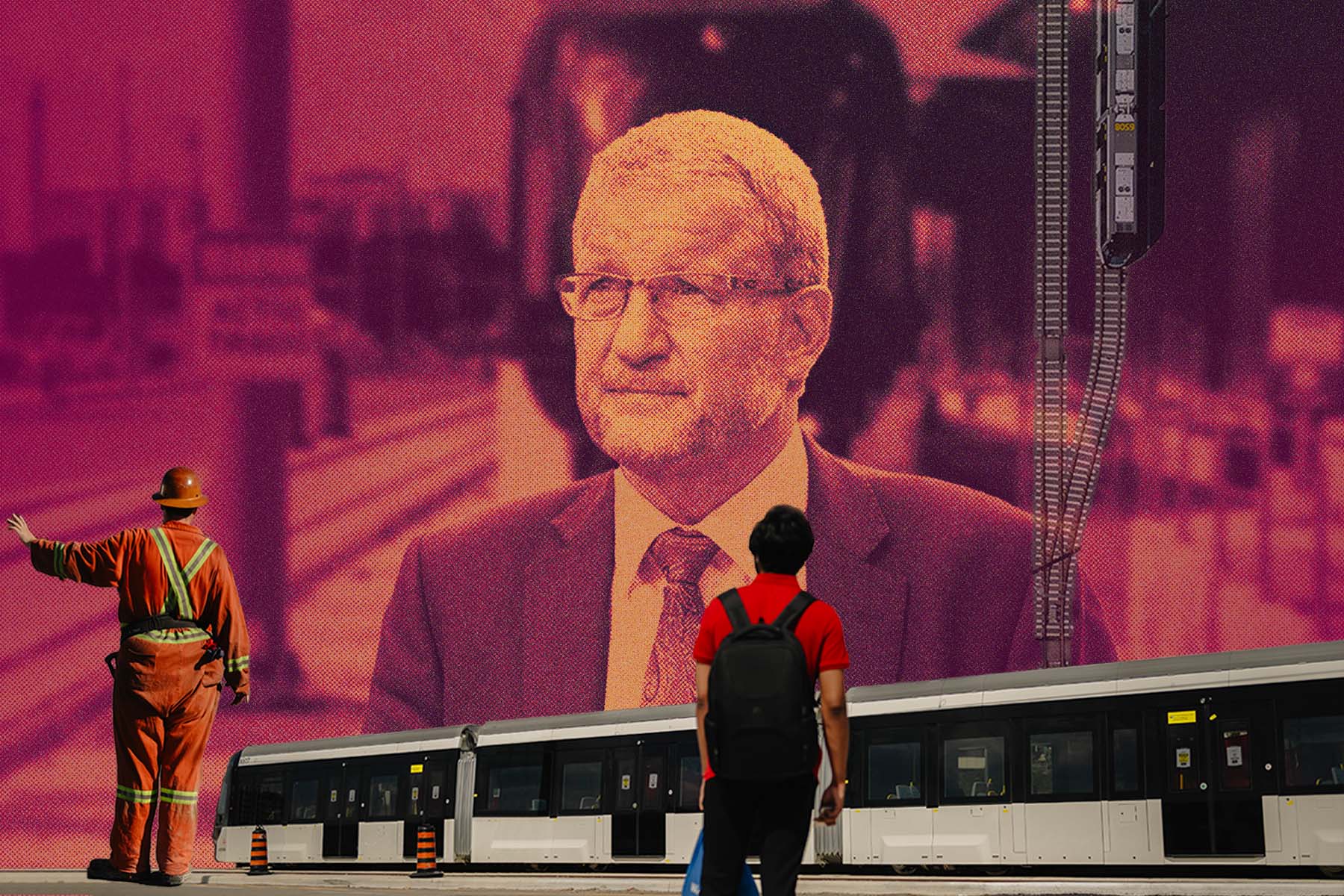

Funded by donors and powered largely by volunteers like Windsor, this 108,000-square-foot facility, almost two-and-a-half times the area of Yonge-Dundas Square, operates with the efficiency of a grocery giant. As line-ups to food banks around the city have lengthened to snake along entire blocks, the Daily Bread has ramped up its output accordingly to about 160,000 lbs of food per day, according to the organization’s chief executive officer Neil Hetherington.

“We’re going to feed the need as long as it’s there. We’ve made that commitment to the city,” he said.

The trouble is the need isn’t going away. It’s skyrocketing.

The first formal food bank in Canada was established in Edmonton in 1981 as an emergency response to feed those in need amid an economic recession. Today, food charities, including food banks, drop-in meal programs, and shelters, have become the country’s go-to answer to hunger. What started out as a temporary measure to help people during hard times has ballooned to the point where there are four times more food charities in the country than grocery stores, according to the food charity Second Harvest.

The growth of these charities and the efforts of canned food drives, fundraising campaigns and volunteers have done little to stem the demand, however. Those who work in the sector recognize giving out food doesn’t solve the fundamental problem that drives people to use food charities in the first place—the problem of not having enough money.

The most recent Statistics Canada data showed in 2021, 18.4 percent of Canadians, or 6.9 million people, across all 10 provinces lived in households that experienced food insecurity, ranging from marginal, where they worried about running out of food, to severe, where they missed meals or went entire days without food. And in the aftermath of COVID lockdowns and amid soaring costs of living, food charity operators in Toronto say the demand for their services has reached unprecedented heights. As they advocate for all levels of government to step in and prevent people from sliding into poverty, they are bracing for a worsening crisis of deprivation, and the need to rely even further on the generosity of donors and volunteers like Windsor.

“We are really filling the hole in a social safety net that is crumbling, that is fraying and breaking,” said Sarah Watson, director of community engagement at North York Harvest Food Bank, the Daily Bread’s counterpart that serves northern Toronto.

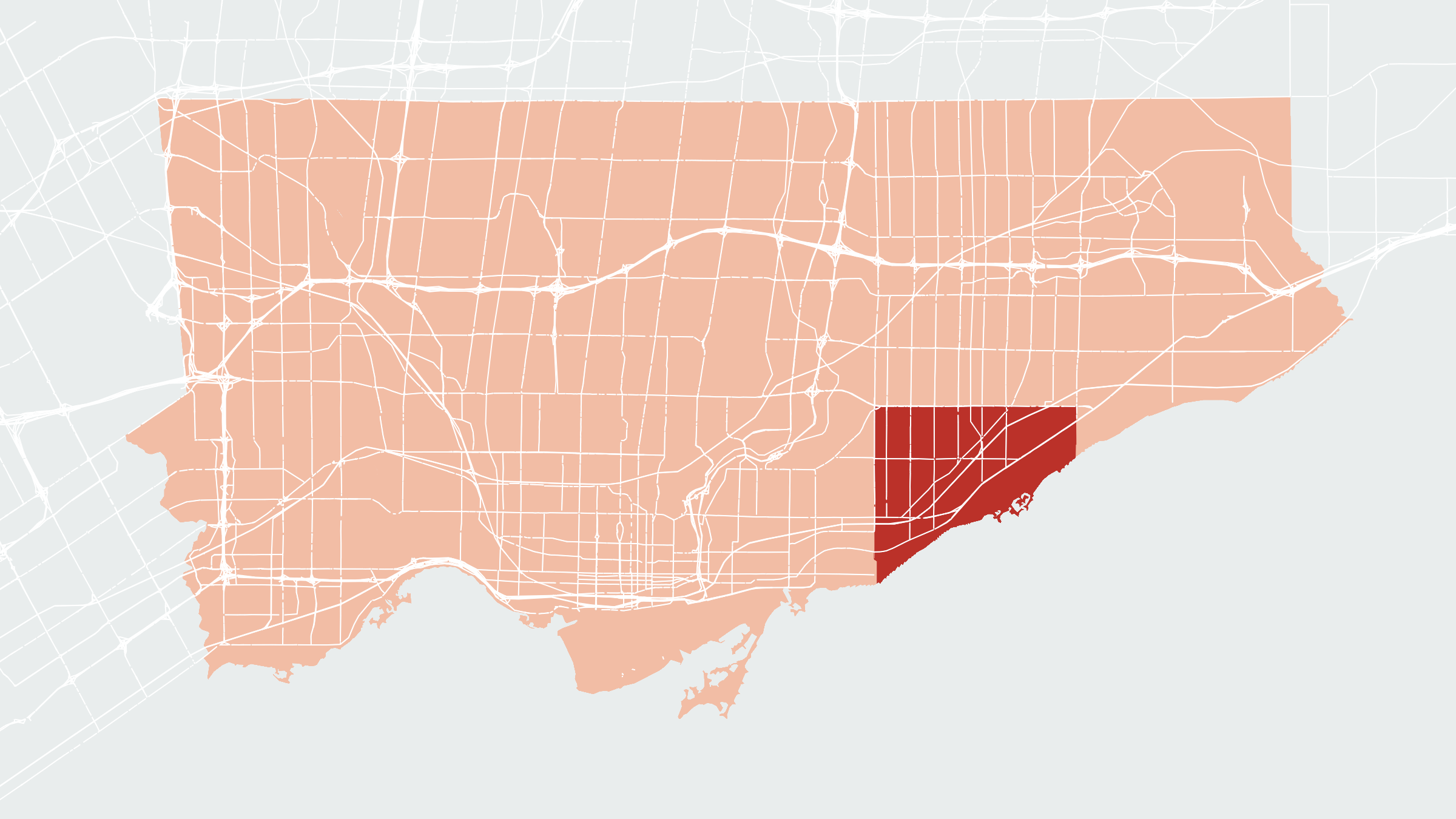

Data from these two major food banks show a dramatic spike in usage since the start of the pandemic.

North York Harvest Food Bank recorded 242,072 client visits in 2022, nearly 54 percent more than in 2019. The increase is even steeper at the larger Daily Bread Food Bank, which had more than 274,000 visits to its member food banks this August alone. That’s nearly four times the number before the pandemic.

To put these figures into perspective, imagine filling the Rogers Centre to capacity seven times.

“That’s how many people we’re serving every month,” Hetherington said.

If you look more closely at the Daily Bread’s client visit numbers, you see two distinct jumps. The first, during the first year of the pandemic, is no surprise. Many businesses were shuttered during COVID lockdowns. Schools and daycares, where children may have had access to breakfast clubs and lunch and snack programs, were closed. Workers who didn’t have paid sick days lost income if they became too ill to show up. And many people, especially those who didn’t qualify for the federal Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and Employment Insurance, quickly burned through any savings they had.

The second, sharper increase starts at the beginning of 2022, and its long tail continues upward out of sight.

To the city’s food bank operators, this, too, has not been unexpected. Even in the early days of COVID, they predicted the rising demand wouldn’t peak until later, Watson said. After the 2008 global financial crisis, food bank use didn’t reach an apex until two years after the economic crash, when many people felt life was starting to get back to some semblance of normal, she said.

“That’s what we anticipated happening through the pandemic,” she said. And sure enough, “that’s what we are seeing.”

This current surge in food bank use is the result of a confluence of factors, Watson explained. There’s a shortage of decent work, a lack of affordable housing, and high inflation.

According to City of Toronto figures posted in March 2023, the average market rent climbed to $1,538 per month for a one-bedroom apartment, up 21 percent from $1,270 in 2019. Anyone currently searching for a new place, though, may be hard-pressed to find such accommodations at that price. The average asking price of a one-bedroom apartment in October was more than $2,600, according to Rentals.ca.

Although inflation is now rising at a slower pace, the Consumer Price Index, which measures how much a figurative fixed basket of goods and services changes over time, rose 6.8 percent on an average annual basis in 2022, marking the biggest increase in 40 years, Statistics Canada reported. Grocery prices increased at their fastest pace since 1981.

The fact that one’s money doesn’t go as far as it used to has forced a lot of people who never thought they’d need to go to a food bank to now turn to them, Hetherington said.

“I used to say the person using a food bank is the person sitting across from you on a streetcar,” he said. “But now, it’s the person sitting across from you in a cubicle.”

Newsletter

Sign up to our free newsletter to get award-winning journalism delivered to your inbox.

This sounds like hyperbole, until Hetherington offers a real-life example. He recalls encountering a parent he knew in a food bank line-up, who was earning $50,000 per year at her broadcast media job, “which, you know, is a really decent salary,” he said. But after paying taxes and $2,200 a month in rent, she was struggling to afford food for herself and two children, never mind transportation, clothing, internet access, and other expenses.

“You can say: ‘Okay, there is something fundamentally broken that requires somebody who is working full-time who still has to make use of food charity,’” said Hetherington.

As worrisome as it is that a growing number of working people are struggling to make ends meet, food charities are also seeing another problem, one that some experts say is the most egregious and stubborn issue: insufficient government support is keeping society’s poorest, including those on social assistance, from climbing out of poverty.

According to a 2022 report from the Daily Bread and North York Harvest, 10 percent of food bank clients that year were temporary residents and 4 percent were refugee claimants. Food bank use among newcomers to Canada sometimes leads to inaccurate, xenophobic claims, Hetherington said. But in reality, newcomers tend to leave the food bank system quickly, he said. “The people that stay with the food banks the longest, generally, are not the immigrant population.”

“I used to say the person using a food bank is the person sitting across from you on a streetcar. But now, it’s the person sitting across from you in a cubicle.”

“I go by Nana,” said the strapping woman in a Toronto Police baseball cap, introducing herself. Her hat partially concealed a head of closely shaved, sterling hair.

Nana has been using food banks for—“Oh my God, years,” she said.

She has an easy laugh and a habit of calling strangers “honey.” She’s a straight-shooter—“Ask me anything,” she said. Nevertheless, to protect her privacy, she prefers not to have her full name published.

Despite not having much money, Nana said, food is not her main concern. She’s resourceful. She knows how to grow cucumbers, tomatoes, and strawberries. She is constantly helping other people, and receives help in return. Just the other week, she said, she gave someone homemade soup she got from a church, after they bought her some vitamin D supplements. Moreover, she’s very good at walking into a No Frills and saying to the staff, “You know what? Listen, I’ve got, like, $40. Give me a really good deal on buying whatever I can.”

Until recently, Nana rented a basement apartment, but she came to an agreement with the landlord to move out in early October because she didn’t have the money to stay. It was time to leave, anyway, she said; the apartment was an illegal rental unit, it had windows that didn’t fully close, and the landlord wanted to rent it out for $2,000.

Since then, she has been staying with her son’s girlfriend.

Nana, who has worked in all kinds of jobs, including as a private investigator, says she is on the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP). According to the province, a single person with no dependent can receive up to $1,308 a month on ODSP. A single person on Ontario Works, which provides support for people who don’t have enough money for things like food and shelter, can receive $733 a month.

A serious highway collision in 1999 left her with a broken pelvis and what she suspects is a pinched nerve that still troubles her leg and back.

More than a year ago, she found out she has skin cancer. The doctors don’t yet know how deeply the cancer has spread, she said. But she can feel it, a big lump beneath her skin. ODSP doesn’t cover the medicated cream she’s meant to use for it. It costs $250 for a 200mg tube.

In spite of her health troubles, her number one priority is finding somewhere to live, preferably for $1,100 a month or less.

“Before I can go back into work, I need to find a place. That’s the base,” she said.

Nana is a survivor. She describes herself as such. She expresses gratitude for all she does have, and she weathers whatever life throws at her with a sense of humour.

“You have to, ‘cause it’ll drag you down,” she said.

Given what she receives through ODSP, Nana would be considered in “deep poverty.” According to Hetherington, “deep poverty” means earning less than 75 percent of the poverty line. That poverty line in Toronto, he explained, is $2,302 per month for a single person.

Individuals like Nana, who rely on social assistance, don’t account for the surge in food bank client visits. They are a segment of the population that has always been there. And that, Hetherington said, is something that desperately needs to change: “It’s obscene.”

The amount of money that people receive on disability can put them as much as around $1,000 a month below the poverty line, he said. And they often don’t have much of a cushion to fall back on. Ontarians must show they are in financial need and have assets that are within certain allowable limits to be eligible for Ontario Works or ODSP.

“So you have to lose all of your savings in order to get an income, right? And then, once you get that income, you are legislated to be in poverty by a significant amount of money,” he said. “And that is fundamentally wrong.”

Even though different levels of government have boosted social programs and financial supports, such as a recent 6.5 percent increase in ODSP, and indexing the Canadian Child Benefit and seniors benefits to inflation, these measures still aren’t enough for those at the very bottom of the economic spectrum, said Valerie Tarasuk, a professor emerita in the department of nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto and principal investigator at PROOF, a research program studying policy approaches to food insecurity.

Part of the problem is these supports are not based on what people actually need, she said, noting it’s unclear what the underlying assumptions are about what people are able to buy with the amount they receive. For example, a family with an annual income of less than $30,000 and a 15-year-old child could augment their income with roughly $6,000 through the Canadian Child Benefit. However, that $6,000 isn’t enough to rent an extra room in an apartment for that child for the year, she said. It might help buy food and some clothing, perhaps.

“But what was that amount of money supposed to achieve?” Tarasuk said. “What is the logic for these benefits? What are they supposed to be buying?”

In an email, Employment and Social Development Canada provided a list of social programs and income supplements that it said helps improve Canadians’ ability to meet basic needs, including food. That list included the Canada Workers Benefit, the Canada Child Benefit, Old Age Security, and Guaranteed Income Supplement. The federal department did not, however, answer what people are meant to be able to afford to buy with those supports.

The Local did not receive a response from the Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services to questions about rising food charity use and what recipients of ODSP and Ontario Works are meant to attain for the money they receive.

When it comes to answering the question of how we got here, to a place where so many people are relying on food charities to get by, Tarasuk’s voice carries an edge of frustration.

“Somehow we’ve gone on for years and years and years with a whittling away of some basic logic for [how] we support people at the bottom end of the spectrum.”

“Charity exists where policy doesn’t. Full stop.”

In the 1980s, when Tarasuk began her research, the food charity landscape in Toronto looked very different.

Back then, the idea was that food charities were temporary, a stopgap to pick up the slack created by an economic recession, she explained.

“But all they ever did was get bigger,” she said.

The trouble is, when everyone is chipping in through charity and celebrating themselves for doing that, it doesn’t create an imperative for government responses. “How can that ever become a rallying cry for social change?” she said.

In those early days, Tarasuk added, the fact that food charities were donor-driven meant they could only give what they received, rather than responding to people’s actual needs. If all they got were potatoes, then recipients only got potatoes. If all that was donated was lettuce, then that was all they could distribute.

“And God help you if you didn’t take it because as soon as there was a rejection of food, it would be seen as a question of legitimacy of your need,” she said.

Since then, some charities have adopted ways to accommodate people’s food preferences and nutritional needs. For example, the Daily Bread buys certain foods that they don’t receive by donation. Even so, Tarasuk said, food charities don’t convert anyone who is food insecure to being food secure.

In 2021, Second Harvest published a report, titled “Canada’s Invisible Food Network,” that showed there are now more than 61,000 food charities in the country, roughly four times the 15,433 grocery stores across Canada. In Ontario, it tallied 21,502 charitable food organizations, compared with 5,368 grocery stores. These include places of worship, community and drop-in centres, schools and other programs that provide food to people who may not be able to afford to buy it.

To Second Harvest’s chief executive officer Lori Nikkel, this extraordinary ratio says two things. First, Canadians are extremely generous, she said: “When we see a problem, we will try to solve it as individuals.”

Second, she added, the country has a huge policy framework failure.

“We have built out a system of charity to manage people eating, which is outrageous,” she said. “Charity exists where policy doesn’t. Full stop.”

Nikkel paints a bleak picture of what society would look like if food charities were to disappear, without any new policy interventions. Food charities are not only necessary because they provide people with food, she said, many also provide other services, such as helping them get addiction treatment or find safety from domestic violence.

Without them, she said, “You’d just see poverty everywhere, all the time. There’s no escape.”

Even though the reasons people rely on food charities are complex and manifold, it’s not as though there aren’t solutions.

Every November, the Daily Bread and North York Harvest publish a “Who’s Hungry?” report that provides a snapshot of who in Toronto is using food banks and why. And every year, their report offers recommendations. Last year’s version included a wide range of detailed policy measures to help the working poor, provide more financial security for those with precarious employment, improve social assistance, and increase affordable housing, among others.

The challenge is in making sure these policy recommendations are implemented.

Hetherington said he meets with a lot of elected officials of all political stripes. Invariably, he said, the meetings go like this: He’ll tell them what is happening in their ward or riding. He’ll tell them where the food banks are, and will give them grim numbers. He will then explain what the situation is like in the city. They will express concern and ask what can be done to solve the problem. Hetherington will then offer policy recommendations, often many of them.

“And then, they put their arm around me and they say, ‘You’re doing a good job. I’m so grateful that the Daily Bread is here for the city.’ And then, I leave,” he said. “And so they know the problem. They know the solutions to it.”

Being told the food bank is doing a good job may be a welcome compliment. But, Hetherington said, “I need them to do a great job, too.”

In an ideal situation, Hetherington imagines that his organization’s advocacy efforts are so successful that everyone enjoys the right to food. In this vision of the future, he said, the Daily Bread building would be demolished, all 108,000 square feet of it, and replaced by affordable housing.

“I really would love there not to be a food bank,” he said. “The goal is that we’re not here.”