Isaac Crosby is Anishinaabe and Black, and he wants his family’s history to be seen.

“I come from two of the strongest cultures on this Earth,” said the 49-year-old lead in Urban Agriculture at Evergreen Brick Works.

I first met Crosby at an Afro-Indigenous gathering on October 2019 at the Children’s Peace Theatre. Over 20 people arrived at the event, which took place to honour people mixed with the blood of the African diaspora and Indigenous people of Turtle Island.

I’m Black and Mi’kmaw from Elsipogtog First Nation and I felt validated at the event, hearing others that looked like me talk about the anti-Black racism they face in Indigenous communities and the anti-Indigenous comments they overhear when people don’t realize they’re Indigenous.

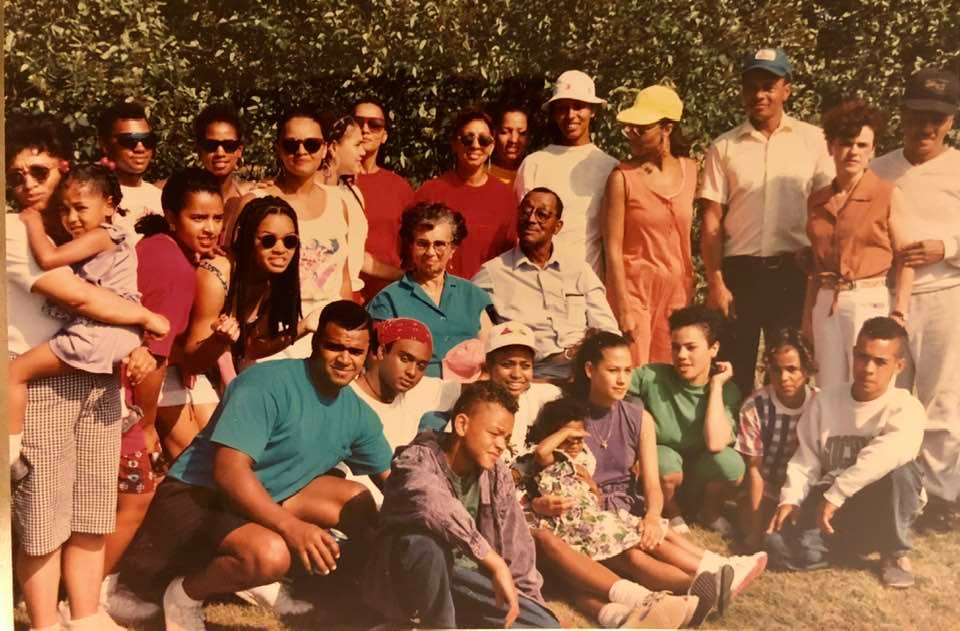

As the talking circle landed on Crosby, his smile was striking, bright, wide, and brimming with laughter. His eyes lit up as he poured out his wealth of knowledge about growing things. And as Crosby shared his story about growing up, it was a lot different than mine. As a child I thought only my sister and I shared our mix. But his entire family was also Anishinaabe and Black, and he grew up embracing both cultures. His family comes in many shades. Crosby’s mom has light skin with freckles, others come in darker hues, but they are all Indigenous.

His home community is the Ojibwe of the Anderdon near Essex county, over 300 kilometres south-west of Toronto. He prefers the term Indigenous with Black ancestry because he wants to honour his connection to the land first, but he also uses Black Indian.

Crosby lives and works in Toronto, after moving here over 20 years ago. Early on he heard outright dismissals of his ancestry and remembers a former coworker saying he had to choose one. But honouring both bloodlines is important to Crosby. Another former colleague said his ancestry was a “double whammy.”

“I don’t see it as a double whammy,” said Crosby. “I see it as a double blessing.”

Both instances caught him off guard, but they didn’t shake his love for his people. He thinks those instances of ignorance point to a larger problem—that the history of Black and Indigenous relations has largely been erased.

“When you look at the history of these two cultures and their meeting you actually see the birth of North America”

When most people think of multiracial Indigenous people, they tend to think of white-Indigenous people. Because of white supremacy, Crosby’s family’s history, the history of the Black Seminoles, the Underground Railroad ending in Indigenous communities, and the complex history of Joseph Brant have largely gone untaught.

“When you look at the history of these two cultures and their meeting you actually see the birth of North America,” said Crosby.

His work in horticulture at Evergreen Brick Works centres on helping Indigenous youth reconnect to farming traditional foods, and he thinks the patch of nature at his work is essential for all Indigenous people to stay grounded. It’s a place where people can come to hold ceremonies or just stick their feet in the dirt again.

Crosby also advocates for food sovereignty in Indigenous and Black communities. From his years of research, he knows Indigenous and Black people have helped feed the world. Coffee, watermelon, and okra originated from Africa, while tomatoes, corn, and potatoes originate from Turtle Island. And those foods helped other countries grow. He’s also seen what his cultures can create with poor quality foods and he likes to envision the cuisine they could create with full autonomy over their food supply.

Crosby’s lineage stems from his Anishinaabe ancestors taking in a blend of Shawnee and runaway slaves. The Shawnee were expelled from modern day Ohio and had already intermarried with the Black runaway slaves before they were forced north. Crosby has always been intrigued to learn about his roots, and his research findings included many ways in which Black and Indigenous people were discouraged from coupling, including anti-marriage laws between Black and Indigenous people. Other laws encouraged Indigenous nations to return runaway slaves, and the historic “one drop rule” in the United States reclassified many dark-skinned Indigenous people and those of mixed ancestry as Black. Only the white Indigenous were allowed to stay Indigenous, and Indigenous people with Black ancestry have faced that erasure since.

“We’re still here, we’re still standing up and claiming our right to existence,” said Crosby.

Crosby comes from a long line of Indigenous people with Black ancestry that settled in the Anderdon area, which is still fighting for recognition through a band creation and land claim. Crosby says when most people think of the area, they think of the Huron-Wendat, but he says his Anishinaabe ancestors were stripped of their land through colonization. According to Crosby, his family’s early community was decimated by the war of 1812. Able-bodied men joined the war, while others strong enough fled and joined other communities, leaving only the young and old. Then a local Indian agent sold their land without permission and kept their money.

But a group of Black Shawnee—Shawnee that were mixed with runaway slaves—sought refuge with the dwindling community and married into the Anderdon families. Three prominent families emerged, the Nolans, Walls and Maulders, and they started building a farming community. Crosby said each pairing had 10 to 15 children, rebuilding the nation.

After years of hardship, his family is bustling and maintains a farm homestead. Every year on August 1, they have a reunion to celebrate Emancipation day. Over 50 people still live on the farm and hundreds come from all over Turtle Island to reconnect to the land during the reunion.

“We are still farming there, our blood is still there, and we are going nowhere,” said Crosby, proud of his family’s commitment.

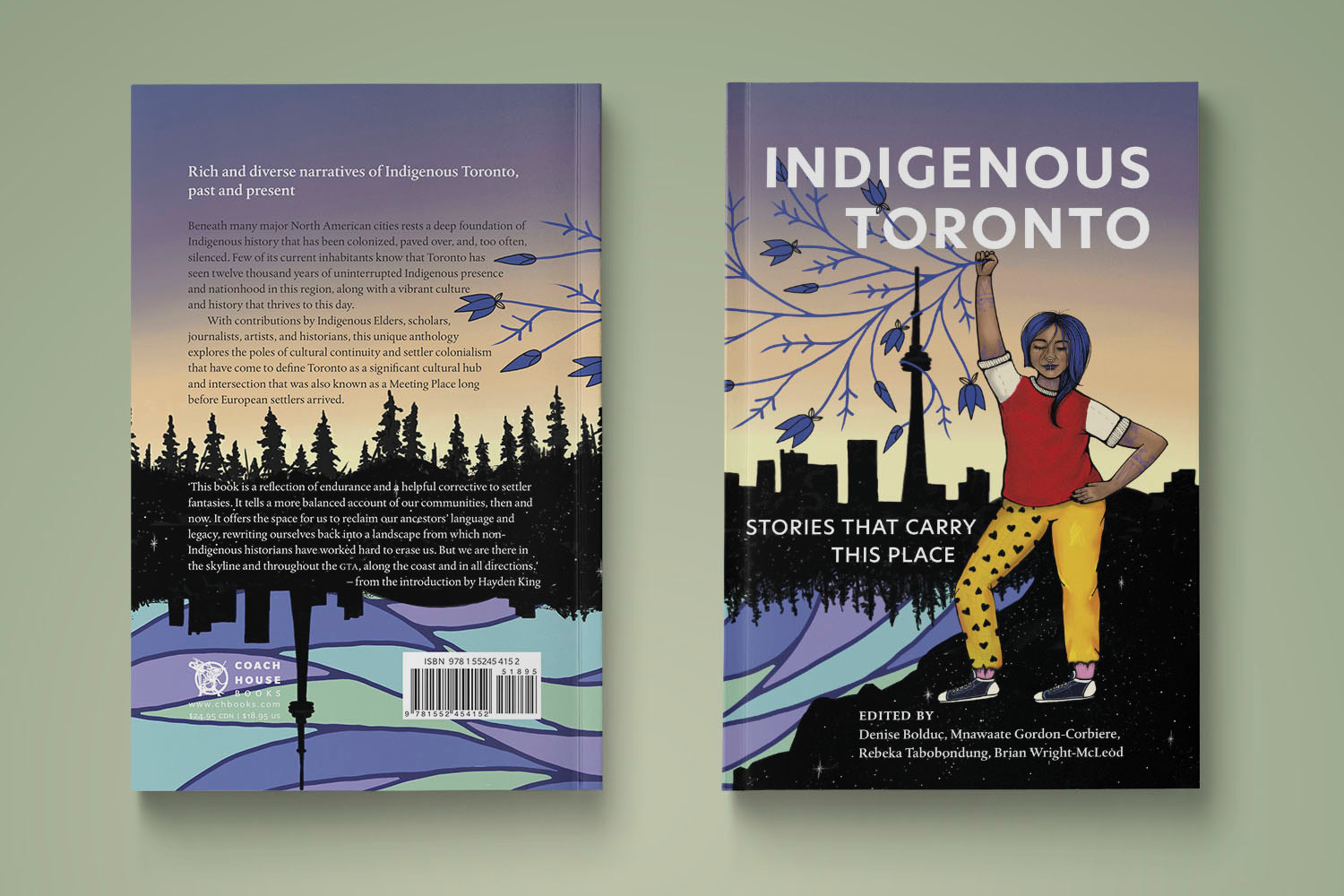

He believes that Canada and Toronto need to do more to acknowledge the historical and current existence of Black and Indigenous people. Most of the historical stories of Black and Indigenous relations are based in the U.S., but he and his family are living proof it happened in Canada. He also wants to see Toronto-based Indigenous organizations do more to celebrate Indigenous people with Black ancestry, to mark Black history month and talk about their shared history.

For allies, he’d like to see them do more to confront racism. “When you hear anti-Black or anti-Indigenous stuff, you have to step up and say something,” he said.

Crosby cringes when I mention some lingering anti-Black sentiments in my home community and jokes that if Indigenous people shake their family tree hard enough, a Black person may just fall out. In his research, darker-skinned Indigenous people were sold as slaves as well, and lingering anti-Blackness is still connected to a Eurocentric way of thinking and is linked to past trauma.

But having Black bloodlines is something to be celebrated.

“It’s a double blessing to have the blood that I have running through my veins,” said Crosby.