As a mixed Huron-Wendat, Scottish, and Irish woman living in Hamilton, reading Indigenous Toronto taught me that the city my son and I call home is the same land that my ancestors lived on.

Our reserve, Wendake, is located just outside of Quebec City. My mom moved to Hamilton to be with my Dad when she was just 19 years old. From birth I’ve always been an urban Indigenous kwe and I knew that our Wendat traditional lands, before settlers and treaties, were close by.

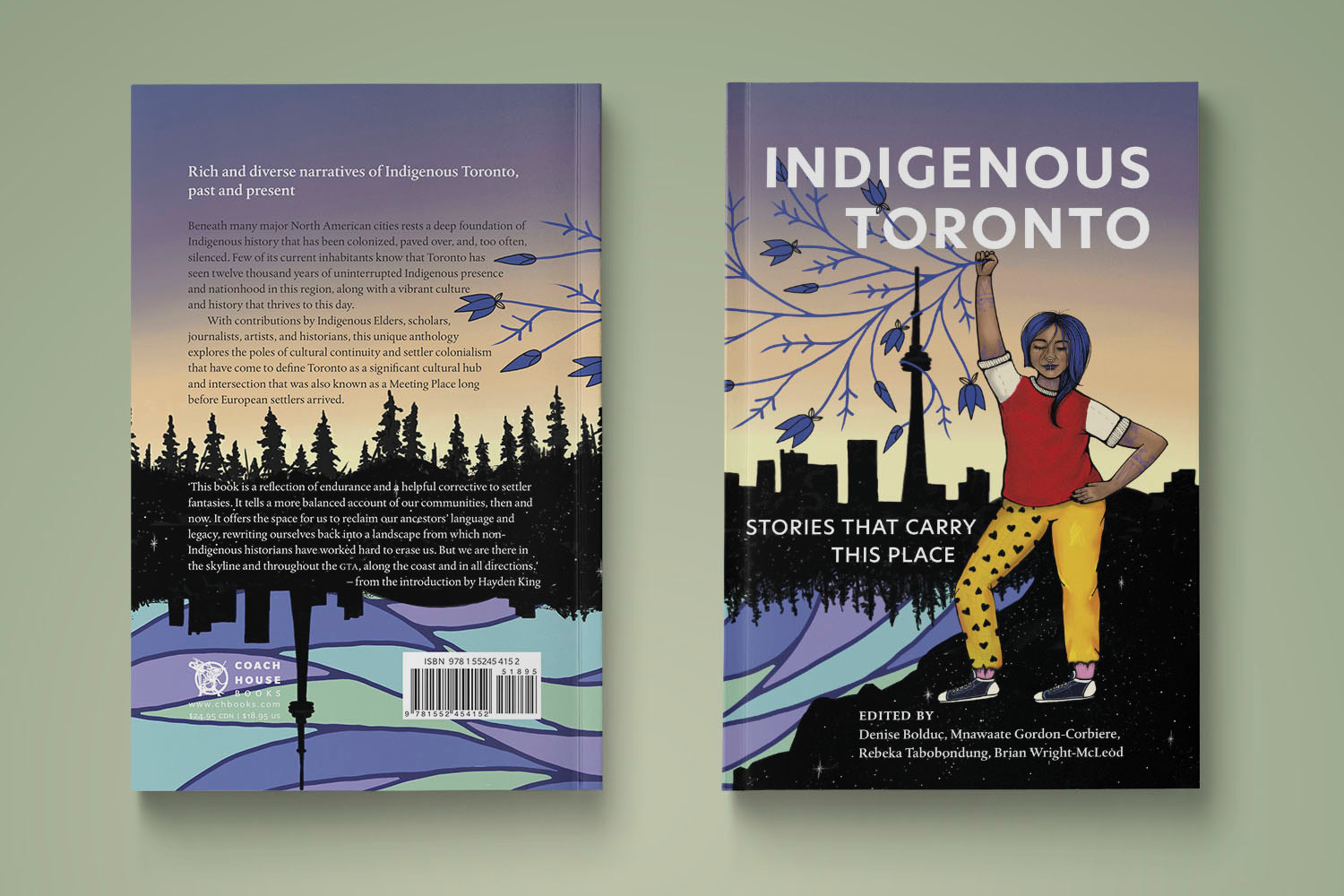

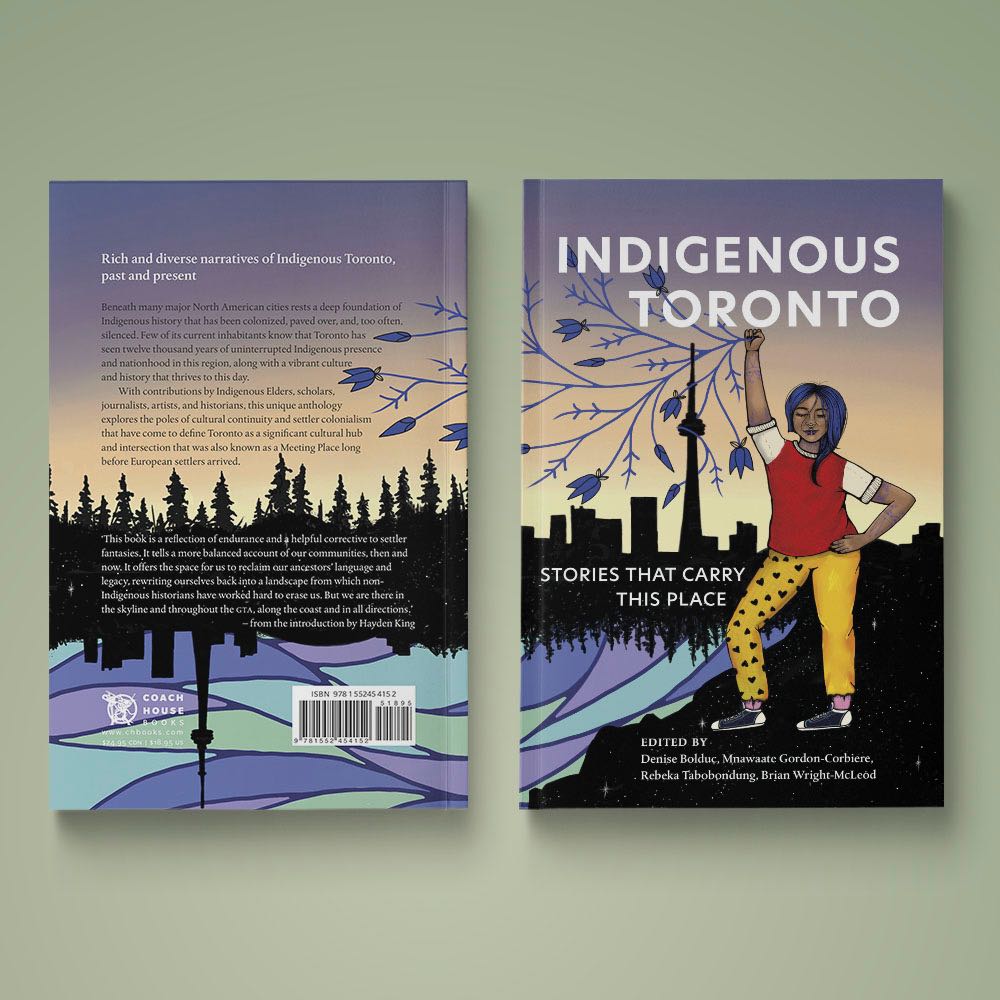

Within the first few chapters of Indigenous Toronto (Coach House Books), a new collection of essays edited by Denise Bolduc, Mnawaate Gordon-Corbiere, Rebeka Tabobondung, and Brian Wright-McLeod, I learned about how my ancestors, along with the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee, occupied the land that stretches from what is now known as Hamilton to Toronto.

Indigenous Toronto tells of the true Indigenous history, stories, people, and places of this land and territory. It starts from the beginning, when we occupied this land prior to contact, and moves to the present day—from treaties being signed, to our relations helping to shape the city into what it is today, to the Indigenous peoples that are currently living, working, and playing in Toronto.

“…it has to be acknowledged that the histories of Toronto are typically histories of violence. We endure nonetheless. This book is a reflection of that endurance and a helpful corrective to settler fantasies. It tells a more balanced account of Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Wendat communities, then and now. It offers the space for us to reclaim our ancestors’ languages and legacy, rewriting ourselves back into a landscape from which non-Indigenous historians have worked hard to erase us.” – Hayden King, “Rising Like a Cloud: New Histories of ‘Old’ Toronto”

Following an introduction written by Hayden King, an Anishinaabe sociology professor at Ryerson University, Indigenous Toronto starts out in the right way, with the first three essays going in-depth into the Dish with One Spoon Treaty, the Williams Treaties of the Anishnaabeg, and the Toronto Purchase of the Mississaugas of the Credit treaties, as well as the distinct nations of Indigenous people that resided on these lands for thousands of years prior to contact.

For Indigenous Peoples, everything starts with land. In our creation story, Creator made Indigenous peoples from the soil of Mother Earth. We are a part of the land, and without it, we would be nothing.

Reading about my ancestors on this land thousands of years ago caused a feeling I don’t think the English language could properly explain—the sense of connecting with my ancestors, of feeling and seeing everyone that came before me who called this land home. I’m sure there’s a Wendat, Anishinaabemowin or Mohawk word for the feeling, but I don’t know my language, like many of my Indigenous community members and friends.

They say that when you learn your language is when you truly learn your culture, and learn what it means to be an Indigenous person of that particular nation and ancestry. Our languages are our culture, they are the heart of our traditions and teachings, our values, and the way our ancestors viewed life.

“The Anishinaabe City: Ogimaa Mikana” by Hayden King and Susan Blight looks at the Ogimaa Mikana Project, a language revitalization campaign which brought Anishinaabemowin place names to signs, street names, paths and trails of Toronto. The project’s early works included a piece at the intersection of Queen Street West and McCaul Street, where a sign was installed that read Idle No More above the words Ogimaa Mikana (which means ‘the leader’s path’) to honour and recognize the leadership of Indigenous women in the Idle No More movement.

The project has grown, with installations from Thunder Bay to Ottawa consisting of large-scale murals, banners, countermapping initiatives, and exhibits in gallery spaces.

As King writes, what we usually see of historical signs and plaques in the city “is a Toronto—and a Canada—void of Indigenous peoples, except as criminals or ghosts.” Projects such as Ogimaa Mikana start to bring back pieces of what was taken from us when this city was built and makes a point of letting non-Native Torontonians know and recognize that, whether concrete or forest, this land is Native land, and we are still here.

In “The Dance from Cabbagetown Cones to Shiibaashka’igan Cones” Karen Pheasant-Neganigwane tells the story of her early life growing up in her urban Indigenous family. As a young teen, her mother connected with a well-known Indigenous woman, Millie Redmond, and was introduced to the Indian Centre. Pheasant-Neganigwane’s mother wanted her daughter to get more involved in activities. The result was powwow club.

“Each Tuesday, I hurried home after school for dinner, did the dishes and headed out to 210 Beverley Street to the Indian Centre. The weekly powwow club became a spiritually driven nurturing time for me. I learned the AIM song and listened to stories of those who came from the U.S. or from out west. At the same time, I read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. This was my ‘turn of the switch’ moment.”

The story resonated with me. The Hamilton Regional Indian Centre, or HRIC, was the place I truly started my journey of learning who I am as a mixed Wendat woman and an urban Indigenous woman. When my Ojibway/Anishinaabe husband and I got sober, we started going to HRIC every Wednesday night at 5:00 p.m. for Anishinaabemowin classes.

There we met our relations in the Hamilton urban Indigenous community. I learned how to dance jingle. The first pow wow I ever danced in was the Soaring Spirit Festival, which we call the Hamilton Pow Wow. I danced in that arbour for the very first time, surrounded by my community, and I never wanted it to end. Becoming a jingle dress dancer, and connecting with my community and HRIC have been fundamental parts of my healing and recovery, as well as my journey along the Red Road. Before HRIC, my husband and I were just two Natives living in the city. But now, we’re a part of an urban Indigenous community that we love and cherish. When you’re a Native living in the city, it’s so important to be able to find that community, and places like the HRIC and the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto are the perfect places to do so.

In “Kapapamahchakwew: Wandering Spirit School and the Vision of Nimkiiquay,” by Kerry Potts with Pauline Shirt, we learn about a number of supports and resources started by Indigenous Canadians in Toronto for things such as housing, health and schooling.

Anishnawbe Health Toronto, for example, is the sole provider of western medical and traditional health services to an ever-increasing Indigenous population, offering everything from access to sweat lodge ceremonial grounds, to services for mental health, addiction, homelessness, primary care, education, prenatal, and palliative care.

I’m all too familiar with how important and vital these types of services and resources are to the Indigenous population living in cities. The house that my family and I call home here in Hamilton is through Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services. Our family doctor here is at De dwa da dehs nye>s Aboriginal Health Centre.

Being Indigenous in the city isn’t all that easy, but when we have community, Native Centres, Native housing, and health and crisis supports, it makes it a whole lot easier to succeed, be healthy and happy and live mino bimaadiziwin (the good life).

What makes this book so important is that it’s written by our own people. As Indigenous people, we so rarely get our voices heard or get to have control over the settler perspective and the narrative of our own histories.

The pieces in this collection are the history, as well as the future of a city through the eyes of the people who were here first and are still here. As Indigenous people, stories have always been a fundamental part of who we are. It’s time to take back our voices, share our truths, and have our stories heard.