I can tell what society considers Indigenous art because I go to the airport and I look around in the gift shops. You’ll find woodland style designs, or Inuit stone-cut lithographs, some art from the West Coast based on symbols from totem poles. You’ll find plastic totem poles and maybe a birch-bark canoe, or little dolls of Indigenous girls or women dressed up in fake leather outfits. This is what’s considered Indigenous art in Canada. But it’s also a stereotype.

A while ago, I had an art consultant contact me looking for a huge painting for the office reception of this giant corporation, and she wanted Indigenous art. I don’t know how she got my name, and she couldn’t tell me who the company was. I have a feeling it was like an oil company, something really big. Obviously, dollar signs were flashing in my eyes.

She wanted to see some samples of my work, so I sent her some. And she said, “Well, this isn’t Indigenous art.”

My reaction was: What are you talking about? I’m an Indigenous artist. This is the type of art I create, so it’s Indigenous art.

She said, no, and described what she was looking for, and I knew she meant woodland style. That’s when it really hit home for me that Indigenous artists are being pigeon-holed, and—with some exceptions, like Kent Monkman, whose work I love—if they do anything outside of what’s accepted, it’s not considered Indigenous art.

It just makes me wonder: How can Indigenous artists in Canada break away from the stereotypes in terms of subject matter or style or even materials? I’m sure a lot of other people from a lot of other cultures have the same problem, but I find with Indigenous people, we’re really stuck right now. These stereotypes are really affecting the way people view us, whether we know it or not.

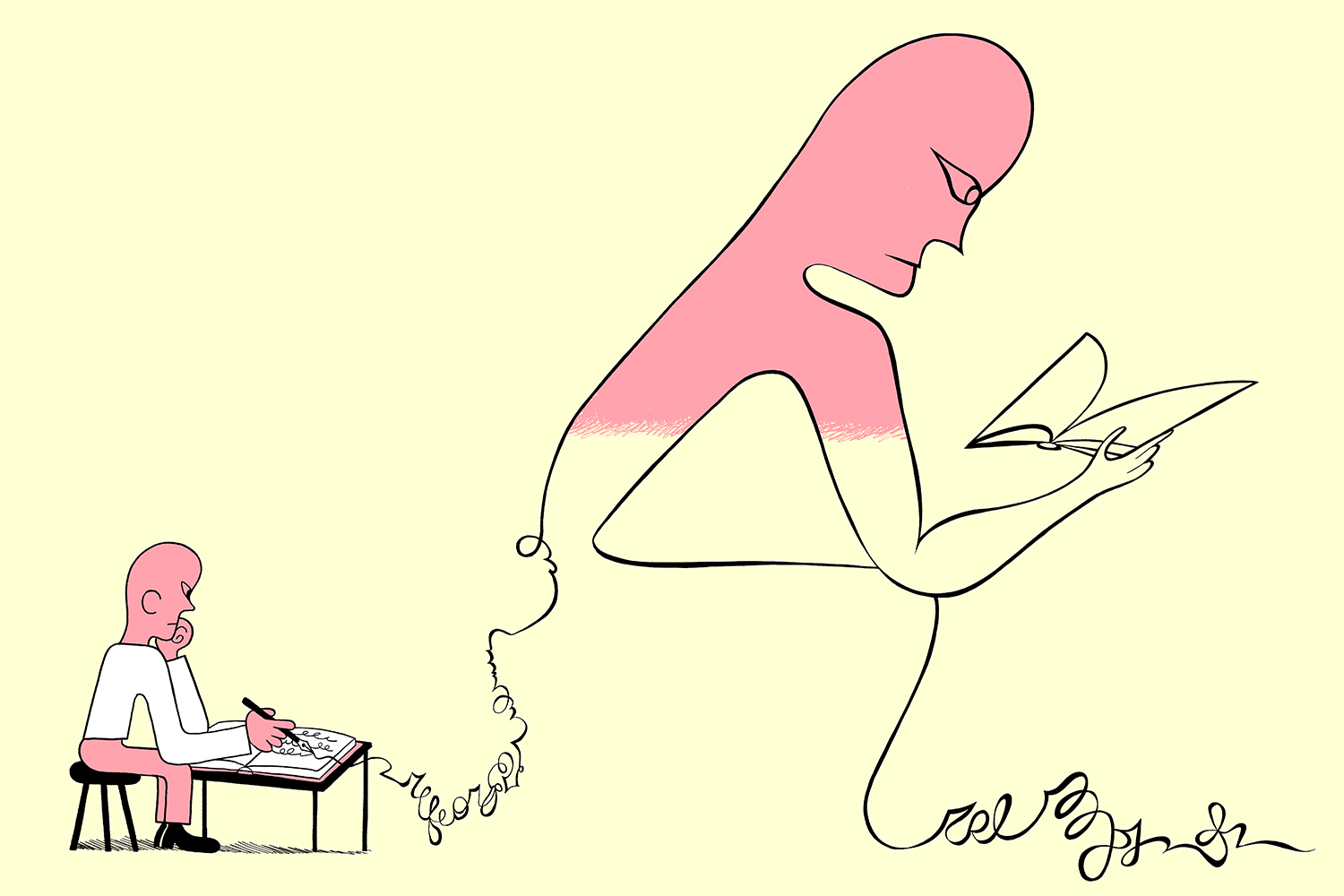

I call it an “artistic reservation” because it’s a way of keeping Indigenous artists constrained within a certain area, artistically, the same way Canada restricted the movement of Indigenous people within a physical reservation. To me, this artistic reservation is almost like a commercial force; it determines what becomes popular and what shapes the marketplace.

When I started working in fine art, I really wasn’t interested in exhibiting or even selling my work. Fine art is a way of expressing myself. It’s a way of bringing out or dealing with feelings. My auntie, she had gone to residential school and she was one of the participants in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. When they were having those interviews, I remember she came over and visited my father and the rest of the family. That was the first time I heard her stories. They affected me in a way that I can’t really explain, but they were the catalyst for a lot of my paintings.

A lot of that work was related to residential schools and different social issues, and I found it was very popular with museums. But obviously, people don’t want to put that type of work in their living rooms, so they don’t sell particularly well. And really, who wants to have a reminder of what Canada has done to Indigenous people in their living room?

I also don’t want my art to be influenced by having to make money. I’m extremely, extremely fortunate that I can teach now and make enough money to put food on the table. That way, I can keep my intention for my art pure. It’s a purity that you need to maintain.

For the York Region District School Board, I’m considered their Indigenous artist-in-residence. With the Toronto District School Board, I’m their educational partner. I don’t teach a subject as such. I work with students from about grade four to grade 8, and I’m sort of their first contact for Indigenous people, the first Indigenous person they ever meet. It’s important for me to give them this positive image because they’re going to carry that for the rest of their lives.

So I go in on the first day, I talk about myself, and my Mohawk culture, my Haudenosaunee culture, about history, treaties, the land, and about the stereotypes of Indigenous art. I talk about my own artistic style, what I create, and why I create it. And then, I’ll tell them a traditional oral story—typically, it’s the Mohawk creation story—and use it as a jumping off point for further work. Over about 10 weeks, sometimes 12, we create some form of art. Lately, it’s been a lot of mural work. We work side by side, and I like doing it that way because I’m working with small groups, and I get to know the students on a more personal level. It’s really fun. Throughout, I’m peppering them with Indigenous knowledge, so hopefully they’ll learn some of the Mohawk language, they’ll learn more about myself as an Indigenous person.

Art + Money

Subscribe to our free newsletter to get our stories delivered directly to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

When I was a kid, a long time ago, we had cough medicine that tasted really bad. So mothers would put sugar in it; that way, you’d still get the benefits of the medicine, but it was sweet, so it didn’t taste as bad. I feel that’s the role of art in Truth and Reconciliation—a way of making the bad taste of Canada’s past more palatable. You can kind of sneak in the truth by showing people some pretty art.

When it comes to breaking down stereotypes, I’m not saying that everybody thinks this way, but I think people need to realize that Indigenous art isn’t a style. It’s an expression of Indigenous experience, Indigenous history and individual thoughts. I tell my students that my art comes from my soul, from who I am—which is the same as all other artists, but my culture is the foundation of who I am. On top of that are experiences; I’ve experienced racism because of my culture, and these experiences affect me. My thoughts about my experiences are what come out as my art. So regardless of what I create, it’s going to be Indigenous art because it’s flavoured by these things.

I suppose I’m trying to say, even if the physical art piece doesn’t look like what you think Indigenous art should look like, look at the inner spirit of the art: this is what people should accept as Indigenous art, rather than the more superficial layer.

—As told to Wency Leung

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Foundation. All stories were produced independently by The Local.