It took Metrolinx just a few days to clear cut a forest of 100-year-old trees in the Small’s Creek ravine. On a snowy morning this February, workers used chainsaws and wood chippers to clear the north side of the forest to make way for a retaining wall, part of the expansion of the Lakeshore East GO transit line. Despite loud protests from community members, and a motion by Toronto city council requesting construction be halted until a restoration plan was put in place, workers kept cutting, felling trees so old they creaked when they hit the ground.

For the members of Friends of Small’s Creek, a volunteer action group that had been fighting the tree removal with protests, write-ins, and community walks for over a year, the clear cutting was an outrage—a blatant breach of protocol for construction in green spaces. It ignored the ecological effects that tree removal would have on the ravine, a rare urban wetland in the Danforth that has been there since well before the first train tracks were laid.

“It was really hard to watch,” says Matthew Canaran, a member of Friends of Small’s Creek. Sheila Boudreau, an urban planner and another member of the group, called it a time of grief and tears. She listed the many ways the forest helped maintain the ecosystem of the ravine: providing shade that regulated the temperature of the water, helping purify rainfall, supporting a network of other plants and animals, and managing the damaging effects of urban heat. “Over 85 percent of the original wetlands in Toronto have been lost,” Boudreau notes. “Rare, urban wetlands like Small’s Creek need to be protected.”

While community members saw the forest as essential to the sustainability of the ravine, Metrolinx saw the trees in a different light: invasive. According to a blog post by Metrolinx, “268 trees were identified for removal, and of these, 205 were invasive species,” primarily Manitoba Maples and Norway Maples. The designation made it that much easier to move ahead with clear cutting the area. “Invasive species are capable of causing extinctions of native plants and animals, reducing biodiversity, competing with native organisms for limited resources, and altering habitats,” the agency argued.

We’ve been conditioned to use the term “invasive species” to single out the unwanted, a plant or animal species that has the ability to spread beyond our control. The language typically used in news reports and ecological studies makes it clear just how unwelcome they are. Invasive species “wreak havoc,” “preying on existing species,” and are considered a “great threat” to our biodiversity. From the sanctioned hunting of invasive animals to the use of chemical pesticides to get rid of invasive plants like dog strangling vine and garlic mustard, we’re encouraged to swiftly cut them down or kill them for the well-being of the environment, regardless of the means.

At its most extreme, the rhetoric around invasive species has parallels with a desire for genetic purity, and the need to prevent hybridization in nature. As a recent article in Vox notes, the idea that a species is not from around here, and so must be eradicated, feels not too far from the way we frame human migration. Borders are patrolled and immigrants are given temporary status in countries to determine if they are amenable to their environment. This nativist bias, when applied to plant and animal species deemed invasive, means we might be less critical of their removal, and feel justified in taking them out of the ecosystem.

In a time of accelerated climate change, however, there’s been a shift in the scientific community around how to classify and manage invasive species. From botanists to Indigenous land stewards, people are reconsidering our relationship with invasive species, and what to do about them. As cities become more densely populated and natural disasters happen more frequently, plant and animal species have been forced to migrate at a more rapid pace to adapt to the continual loss of their environments. All of the world’s ecosystems have been and will continue to be disrupted. A plant that thrived in a specific environment in the 1800s may not do as well in the climate of 2050. As a result, it’s becoming less clear what separates the native from the invasive.

Despite their label, invasive species did not invade North America on their own—we brought them here. Settlers carried them to new lands on purpose, as crops or decorative plants, or by accident, attached to cargo ships or hidden in imported goods. Today, there are 441 invasive plant species in Toronto, growing in parks, parkettes, ravines, and other green spaces. Some of the most pervasive include garlic mustard, an edible herb brought to North America in the 1800s, and European phragmites, a reed that grows in and around ponds and lakes.

These species can indeed cause harm to the plants that were here before them. Garlic mustard can produce more than 60,000 seeds per square metre, displacing native flowers like trilliums and threatening species already considered at-risk, like hoary mountain mint and white wood aster. Phragmites can reach up to six metres high with as many as 200 stems per square metre, growing so densely they crowd out other native wetland plants and reduce the habitat of frogs and turtles.

Judith Jones, an environmental consultant and botanist, has spent the last seven years working on The Manitoulin Phragmites Project to address the prevalence of the invasive reed on Manitoulin Island. “Its ability to spread is just astounding,” Jones says. In 2021, volunteers have already put in 250 hours cutting down large clusters of reeds along the shoreline, but there is still a long list of sites where phragmites have taken over.

But even for botanists like Jones, there is no one way to address the issue of invasive species, especially given the pace of climate change. The clear cutting of trees in the Small’s Creek ravine, under the guise of being invasive, speaks to this complexity, and the larger challenge of preserving Toronto’s 150 ravines. Formed during the last Ice Age, they constitute the largest ravine system in any city in the world, and are home to many of the city’s most common invasive plant species.

The ravine system, along with the 10.5 million trees on city land, are considered key priorities in the city’s overall strategy to create a more environmentally sustainable Toronto. “The ravines and tree canopy are the backbone of the city’s climate resiliency,” says Kim Statham, the Director of Urban Forestry, Parks Forestry and Recreation. With an investment of $82.5 million in the Toronto Ravine Strategy in 2021, one of the cornerstones of the city’s approach is replacing non-native plant species with native ones. Their reasoning is that native plants that have historically grown in ravines and other green spaces create better ecosystems.

But while a ravine like Small’s Creek may not be full of native species, plants that have existed for over a hundred years have nevertheless managed to create a valuable green space—a haphazard collection of Manitoba Maples and Norway Maples that support the growth of native plants like marsh marigolds and swamp asters. From an ecological standpoint, Manitoba Maples are actually native to Canada, but are classified as invasive in Ontario, complicating the lineage of the species further.

“Manitoba Maples are a funny one,” Jones says. “They grow very quickly and they spread, but I don’t know if I would consider them invasive.” She points out that though there are standard best practices for dealing with invasive species in the environmental community, often the best approach is to consider each specific ecosystem and how the species is functioning in that area.

“It depends on what it’s doing and where it is,” she says. “In some cases, the solution could be very clear: get rid of it. But in other cases, it may not be that straightforward.”

“Every plant has a purpose, whether they’re invasive or native,” says Donna Powless, Cayuga from Six Nations, and a member of the Indigenous Land Stewardship Circle (ILSC). “Even a plant like buckthorn.” An ornamental shrub brought to North America from Europe in the 1880s, buckthorn grows all over High Park today. Though it’s not a native species, Powless uses it as part of a traditional soaking mixture for seeds to get them ready for planting.

For Powless and Henry Pitawanakwat, another member of the ILSC, this approach to invasive species reflects their commitment to Indigenous land stewardship, which is built on the need for harm reduction and climate action. From their perspective, seeing value in every plant, regardless of whether they’ve been classified as invasive or native, reframes the way we understand our relationship with nature, and connects the loss of any species with the larger impact on an ecosystem.

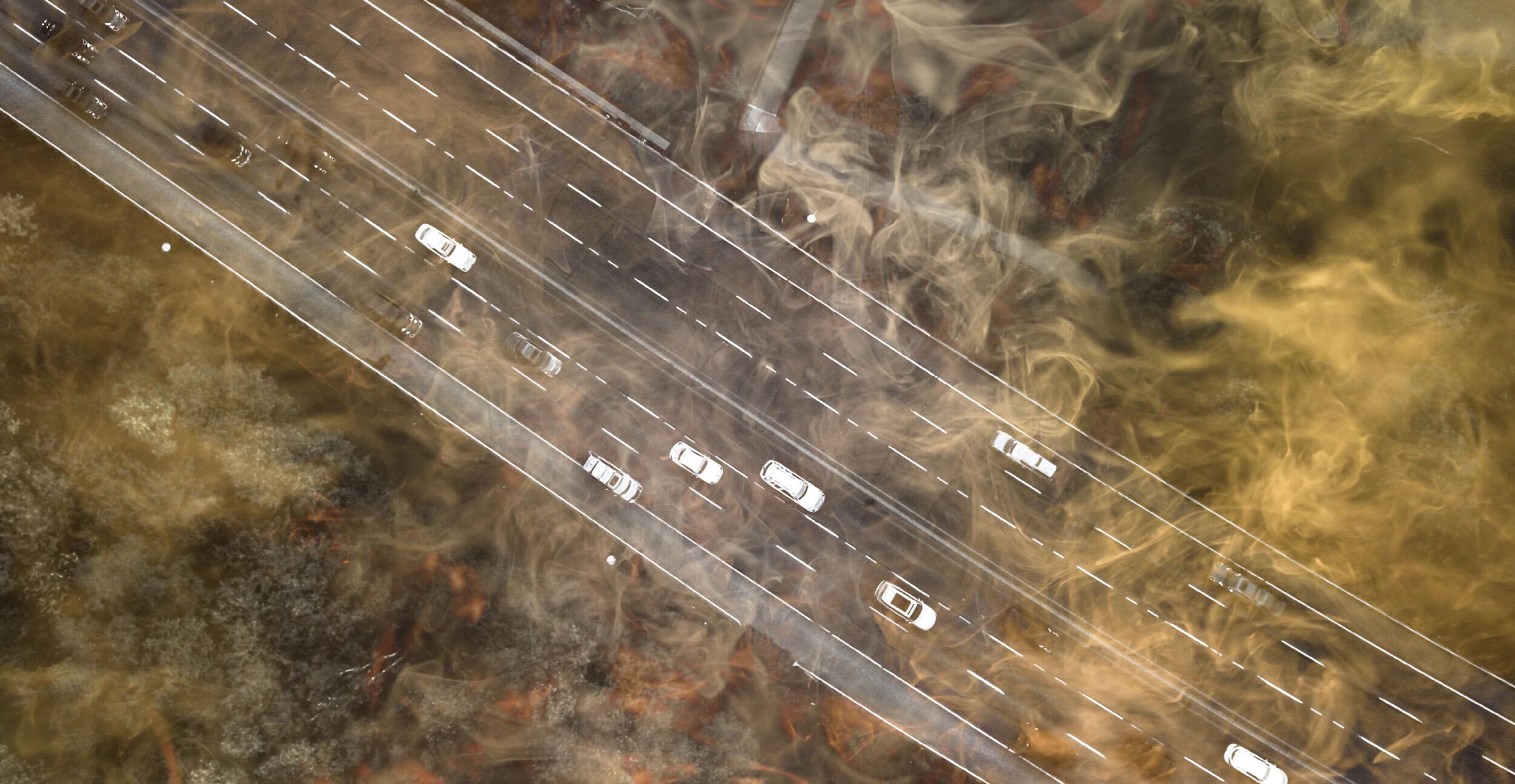

On a clear day in late May, Powless and Pitawanakwat were in High Park as thick smoke filled the air, performing the opening ceremony for the annual burn. Holding traditional drums and singing songs, they watched city workers and firemen carefully light small fires in five grassy areas, creating trails of orange flames on the bush.

Though Indigenous communities have been using controlled burns for centuries to manage unwanted species and restore the land for spring, prescribed burns have only become a more accepted form of land management in the last several decades, and this was the first time Indigenous elders were invited to participate in High Park. The park is considered a sacred space for the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishinaabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. It’s the site of the black oak savannah ecosystem, which was planted by Indigenous people thousands of years ago, creating one of the last remaining savannahs in Ontario.

“Our people have always been here,” Powless says, referring to High Park as her second home. She spends a lot of time in the park, maintaining a garden of plants commonly used in Indigenous practices and visiting her ancestors’ burial mounds scattered throughout the area. In previous years, Powless monitored the controlled burns on her own, concerned about their proximity to the burial mounds, and was relieved that this year she could be more involved in the process.

“When I look at High Park, I’m happy at least some of it was saved,” Pitawanakwat says, lamenting the many hectares of sacred land lost to development. Like Powless, Pitawanakwat is encouraged that the city is taking steps to include Indigenous land practices in their approach to restoring the landscape, though he notes that it’s a long held tradition that he still does on his own property without the use of propane or lighter fluid.

“We do this every spring, once the snow has mostly melted,” he says. “It gets rid of the old roots and in a couple of weeks, everything is green and fresh.”

A prescribed burn is a less damaging approach compared to spraying toxic pesticides in the area, a practice the ILSC opposes. The group also advocates for hand-pulling invasive plants from the root to avoid disturbing the surrounding ecosystem, a less aggressive and more thoughtful approach. Jones, who has collaborated with Indigenous land stewards in her environmental conservation work, agrees that human intervention is needed to get invasive species under control as part of our responsibility to our environment.

“Unfortunately, human beings were the ones who put [invasive species] in the ecosystem,” she notes. “It’s probably going to be up to us to address them and remove them.”

In an ever-urbanizing Toronto, green spaces aren’t just at risk of encroachment from invasive species, but also from roads, retaining walls, and pipes—what city planners call “grey infrastructure.” It’s an ongoing challenge to balance the value of, say, a forest, with that of an additional GO train station designed to get people out of their cars and onto public transit.

Statham, the Director of Urban Forestry, Parks Forestry and Recreation, acknowledges how blessed we are as a city to have a rich collection of forests, wetlands, estuaries, and the black oak savannah, resources other cities facing the ongoing challenges of climate change don’t have. She highlights the economic benefits of Toronto’s green infrastructure: a tree canopy that provides $7 million dollars in structural value by creating shaded areas, preventing soil erosion, and improving air quality, and a system of parks and waterways that save the city $822 million dollars in recreational spending per year. But she also stresses the need for grey infrastructure to allow the city to function and grow, arguing that both types play different, critical roles.

At Small’s Creek, Stratham says, the city is trying to do exactly that. “We try to mitigate the impact to the best of our ability,” she says. “The restoration is ongoing.” Part of the restoration plan, and part of the bylaws, is replacing every tree that was removed with three in its place—three native trees for every invasive species, in this case. But Boudreau and members of the Friends of Small’s Creek think a tree compensation plan is a short sighted response to the clear cutting of mature trees. Whether the trees were technically considered “native” or not, they were an essential part of a living, complex ecosystem that has now been disrupted.

As the city pours millions of dollars into the protection and preservation of wetlands and parks, the community surrounding Small’s Creek is now focused on taking care of what’s left of the ravine, trying to work with Metrolinx to ensure the rest of the construction does less harm to the area.

“Metrolinx will be here and gone, and the people who live here will stay on,” Boudreau says. “Our role as humans is to take care of these spaces for future generations. We just want the creek to thrive the best it can during our lifetimes.”

Canaran, another member of Friends of Small’s Creek, has gone a step further, collecting acorns from the native red oaks that were cut down along with the invasive maples in the ravine. He’s germinating the acorns at home in growing trays so he can care for them over several growing seasons. He plans to eventually plant them in the soil in the ravine, returning native species back into the forest.

“I’m playing the long game,” he says, noting it will likely take at least 100 years for the new trees to reach the same height as the ones that were removed. “But it will be worth it. It has to be.”