Kazik Radwanski arrived in Germany in February feeling apprehensive. He was at the 2024 Berlin International Film Festival to premiere his latest feature film, Matt and Mara, but his was the only English-language film in the Encounters slate, alongside movies from Iran, Argentina, China, and Serbia. “We weren’t sure if the film would resonate with an international audience,” he recalls. “Especially because this feels like our most intimate, personal, subtle film.”

Bringing a tiny Canadian film to a world audience can be stressful enough, but it turns out even the film’s stars hadn’t seen it yet. Starring award-winning Toronto indie actress and filmmaker Deragh Campbell and BlackBerry co-writer, director and star Matt Johnson, Matt and Mara is an often comic drama about a young professor feeling itchy in her marriage when an old friend comes back into her life and the two fall into an emotional affair. The film is a tender, funny portrait of thirtysomething malaise—a story about trying to recapture some of the old excitement and promise of youth, when the future seemed brighter. “It was a strange feeling watching it with them for the first time in this setting,” Radwanski says of sitting next to the actors as the film unspooled.

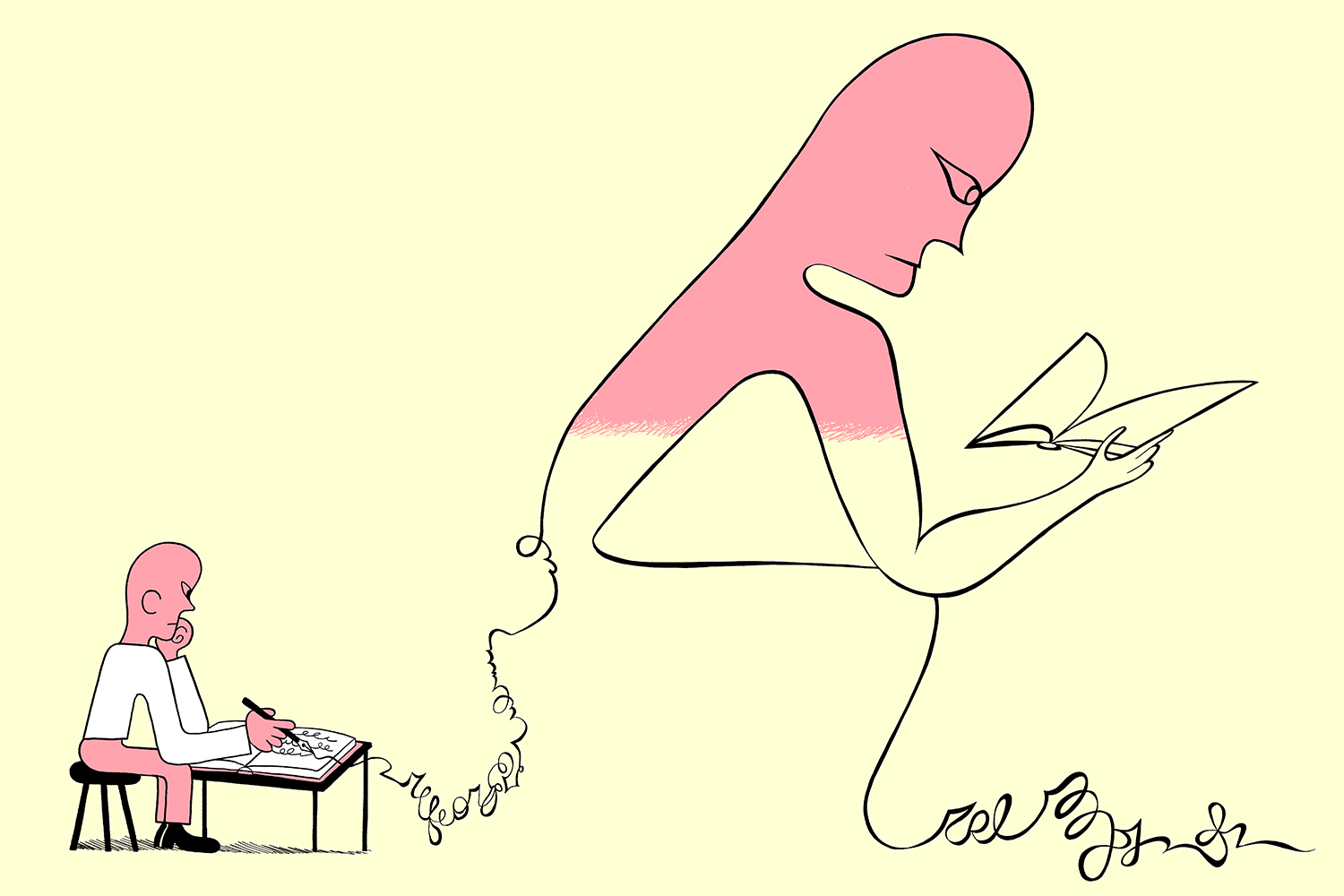

Tall yet unassuming, Radwanski emits an open and welcoming energy in conversation, happy to share the ins and outs of the filmmaking process, and even happier to wax on about the latest films he’s seen making the festival rounds. At 39-years-old, with four independent features and a number of short films under his belt, he speaks with the assuredness of experience, while maintaining the eagerness of a filmmaker whose career is still very much ahead of him.

Matt and Mara’s road to Berlin began almost four years ago, following the complicated pandemic release of Radwanski’s previous feature, Anne at 13,000 Ft., also starring Campbell. The film received stellar reviews, and won a number of awards, including the Toronto Film Critics Association’s Best Canadian Film Award in 2020. It also contained the seed that would grow into Matt and Mara. What had originally been meant as a single-scene appearance from Johnson in Anne turned into a full-fledged supporting turn after Radwanski discovered the actors’ compelling chemistry. On the next project, the filmmaker wanted to take the pairing even further. “On one level, the inspiration for (Matt and Mara) was like, Let’s make a movie for Matt and Deragh together,” Radwanski says. “Let’s get these two and let’s have them crash into each other for the whole film.”

Having an idea is one thing, but getting it made is another entirely for an independent filmmaker in Toronto. For decades, Toronto has been a major movie production outpost—together with Vancouver colloquially known as “Hollywood North.” The city has long been attractive to American producers, with its strong talent pool, lower dollar, tax incentives, and locations that can credibly pass for Anycity, USA. That stature has only grown in recent years, thanks in part to the construction of several large soundstages, making the city a premiere destination for big-budget film and TV production. The Shape of Water, Suits, Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, The Boys and many more call Toronto home, though they rarely if ever depict the city as itself.

While Toronto has had its share of notable homegrown filmmakers over the years—David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, Patricia Rozema, Don McKellar, and Sarah Polley, to name a few—a lack of funding and audience for Anglo-Canadian films has kept things relatively stagnant in the decades after the so-called ‘90s Toronto New Wave, with many aspiring filmmakers jetting off to L.A., or staying home to work on the next Star Trek series. Enter Radwanski and his cohort of young filmmakers, which includes both Campbell and Johnson, who have made waves in Canada and internationally with personal, low-budget films, often set in Toronto. A relatively close-knit filmmaking community has emerged, working together with limited resources to give the city and the country a new cinematic identity.

Art + Money

Subscribe to our free newsletter to get our stories delivered directly to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Some art, like painting, can be done relatively affordably. Movies, even small ones, cost a good deal of money.

Radwanski began his filmmaking career in the late-2000s as a student at Ryerson (now Toronto Metropolitan University) with a series of award-winning, tiny-budget short films made alongside producer Dan Montgomery. Seeking an intimate naturalism that often threatened to spill over into documentary, the filmmaker quickly carved out a space in the emerging landscape of contemporary Canadian cinema, eventually moving into feature work with 2012’s Tower. That film, and its 2015 follow-up How Heavy This Hammer, explored in uncomfortable close-ups the alienation of modern life in Toronto.

In those first features, Radwanski and his friends felt they had nothing to lose, often working for no pay to pull off whatever they could with the negligible resources they had. The digital cameras weren’t necessarily top-of-the-line and he didn’t have the budget for complicated lighting rigs, but he adopted that into his rough, realistic style. The actors often weren’t actors at all, but that became a signature, too.

At some point, however, the economic realities bore down, particularly as ambitions rose and all those friends had projects and lives of their own. “When I think of a film, I think about my main collaborators,” Radwanski says. “How can we design this to make sure that those five or six people are really taken care of?” That means making sure he can pay everyone on the film, and avoiding monopolizing their time. “We’re in our 30s now, and people are starting to have families. A big part of the budget is the work-life balance and being honest about the time commitment.”

Anne at 13,000 Ft. took things to another level, receiving acclaim at festivals, and even securing a small theatrical run in the U.S., a rarity for a tiny Canadian art film. That success got the attention of Telefilm Canada, the country’s premiere film funding body. The director’s first three features had largely been funded through various arts council grants, with budgets jumping each outing, from $50,000 on Tower, to about $300,000 on Anne—small budgets in a local industry dominated by big American television productions, but ambitious in a Canadian art house market that often struggles to reach domestic audiences, let alone international attention and solid profits.

On Matt and Mara, Radwanski’s company MDFF, which he co-founded with Montgomery, proposed a budget around $680,000, receiving a hair under half that amount from Telefilm. MDFF filled the gap mostly using tax credits, and deferred directing and producing fees. Johnson deferred his acting fee in favour of that classic Hollywood deal for points on the back end whenever the film is sold for distribution. Johnson first worked with Radwanski on 2015’s How Heavy This Hammer, where their friendship quickly blossomed. “Now, when I am offered the invitation to come work on any of his projects, I always take it,” says Johnson. “I don’t view it necessarily as working as an actor, but as an opportunity to spend time together.”

The team also received a $100,000 prize from the Toronto Film Critics Association for Best Canadian Film for Anne in 2020, which they immediately invested into the new project. “Having that was a huge blessing, just in terms of bank loans and us being able to float certain costs,” Radwanski recalls.

Watching Matt and Mara, that money is most evident in the array of locations used throughout the film: from downtown Toronto streets, to local coffee shops, university campuses, hotels, and more. Being budget-conscious about location work requires real planning, which can be tricky given Radwanski’s unique style of filmmaking. “There was no formal script. There was a framework, or I suppose, a skeleton of a script,” Montgomery explains. Much of what ends up in a Radwanski film comes out of improvisation and character work with the actors, with a lengthy editing process later on.

As in his earlier films, Radwanski peppered this one with non-actors, including bringing aboard local musician Mounir Al Shami to play Campbell’s somewhat aloof husband and provide some of his own music for the movie. For the film’s supporting author characters, Radwanski cast actual authors Emma Healey and Marlowe Granados. The idea was, the director says, “littering the film with people who have similar lived experiences,” which paid dividends in the film’s sense of realism, including in one very funny scene in which Healey goes on a righteous rant about Johnson’s certain-type-of-male-Canadian-author character.

Even in the writing stage, Radwanski was mindful of what locations would be sensible on a low-budget film, including using his own apartment for some scenes to save money. The first scenes shot for Matt and Mara take place in convenience stores where Mara is getting passport photos done. “Location scouting was going to 50 different convenience stores and like, ‘Can we come back here with a camera?’” Radwanski says. In one of those scenes, the actual convenience store owner appears in the movie, taking the passport photos.

Thankfully, the sheen on film production hasn’t worn off in Hollywood North, meaning many proprietors are very welcoming to small shoots. “Nobody in this city is thinking that these tiny, scrappy productions are cheating, or should be getting a location release or anything like that,” says Johnson. “I think it’s a real paradise for low-budget filmmakers.” Johnson would know, thanks to his experience mounting guerilla shoots for the series Nirvanna the Band the Show, his micro-budget debut feature The Dirties, and every project since.

For Toronto’s indie filmmakers, all that creativity around budgeting often means accepting that they won’t be getting paid for doing what they love. Radwanski himself doesn’t make much of a living through his art. While he’s dabbled in commercial for-hire work, as many Toronto filmmakers do, he earns most of his income from teaching at three colleges and universities around the city. He takes inspiration from South Korean director Hong Sang-soo, who long ago realized he would never make money with his tiny, personal, low-budget movies, and took to teaching—a strategy shared by indie filmmakers around the world like Kelly Reichardt (First Cow), Matías Piñeiro (Viola) and Eliza Hittman (Never Rarely Sometimes Always). “I’ve never really liked movies feeling like a job,” Radwanski says.

When Matt and Mara headed into post-production, Radwanski and his editor Ajla Odobašić hunkered down for the laborious editing process. For the better part of a year, the pair wrangled what was at one point a three-hour cut into a film that runs a brisk 80 minutes. They cut numerous scenes, subplots, and even whole characters, along with paring back talky scenes to reveal their essence in simple, quiet gestures, all while screening the film regularly for friends and family to know it was all working.

Eventually, though, a film needs to resonate beyond just family and friends. Radwanski worked with regular collaborators to lock picture and craft the film’s semi-documentary soundscape while getting the film into the festival in Berlin. Premiering at a major festival isn’t just about showing the film to audiences. “Berlin has one of the largest markets in the world,” Montgomery says.

Distributing the movie properly is extremely important to Radwanski. “The worst fear is it getting lost on [Video on Demand],” he says. It’s not uncommon for a distributor to pick up a small Canadian film and give it a perfunctory digital release, at which point the movie is effectively disappeared from public attention despite wide availability. No deals for Matt and Mara are in place just yet, but Radwanski is proud that Anne at 13,000 Feet’s U.S. distribution deal required multiple weeks in theatres in Manhattan and L.A., along with 12 other American cities. “Even though there’s not necessarily money being made there, we only want to work with a distributor that’s actually interested in exhibiting it,” he says. His goal for his films is modest, though in the wider world of blockbusters and high-profile international movies, it can sometimes feel impossibly ambitious: “I want them to exist. You know, exist in conversations, exist in terms of them being written about, and exist in terms of being screened.”

That conversation, of course, began at the film’s festival premiere in Berlin, where Matt and Mara was in competition with some of the best of world cinema. As a former video store worker and cinephile, Radwanski was thrilled to have his work at a big international festival. “Maybe it’s also the Canadian thing,” he muses. “We’re always very unsure of a film that is celebrated first in Canada; we always kind of like it when it’s celebrated elsewhere first.”

“We’re always very unsure of a film that is celebrated first in Canada; we always kind of like it when it’s celebrated elsewhere first.”

Still, there was trepidation. “You never really know with the German audience if there’s going to be laughter,” Radwanski says. He needn’t have worried. There was plenty of laughter, leading to a fun Q&A with plenty of thoughtful questions from the audience. Critics at the fest liked the film, too. The Film Stage described the movie as “a captivating watch,” while Little White Lies called it a “wry dramedy that refuses to placate us with easy answers or condescension.” Though Matt and Mara didn’t leave Berlin’s market with a big sale, the director is hopeful about its prospects given the reception and a growing international awareness of new Canadian cinema.

In general, Radwanski has seen plenty of positive signs in what has often been considered an artistically stagnant Anglo-Canadian film landscape, particularly in Toronto. Things have come a long way in the 15 years since he started making movies, when larger budget films like Men with Brooms; Bon Cop, Bad Cop; Paschendale; and Score: A Hockey Musical had been the dominant face of Canadian filmmaking.

“It’s changed tremendously,” he says. “I feel like I have contemporaries, or peers. It doesn’t feel so lonely.” Along with Campbell and Johnson, that group includes the likes of Calvin Thomas and Yonah Lewis (White Lie), Sophy Romvari (Still Processing), Antoine Bourges (Concrete Valley), Sofia Bohdanowicz (Maison du Bonheur), Chandler Levack (I Like Movies) and more, all making smaller, more personal work across a variety of genres. Radwanski applauds Telefilm getting into the micro-budget space with its Talent to Watch program, which awards emerging feature filmmakers with up to $250,000 for fiction films.

But it’s not just the money. “Audiences are more and more open to watching something Canadian again, that it’s not this burden of Canadian content being forced on you,” he says. In particular, Radwanski’s seen an attraction among movie fans toward the kind of small, idiosyncratic films he likes to make and that can breathe new specificity and personality into a city better known for pretending to be other cities in American productions. Rather than trying to shoehorn in a Molson- and Tim Hortons-approved version of Canadian identity, movies like Matt and Mara display the real Toronto, from its semi-suburban enclaves and old apartment buildings, to its university halls, coffee shops, public parks, and walkable but alienating downtown core, with all those hospitals and office buildings. It’s the city as it is to the people who live in it, reflected back to audiences who recognize it and those around the world who’ve never gotten to know Toronto in such a personal way. “I think, in general, people are open to more personal work. That it’s less of a radical thing. That they see value in something being specific or truthful,” Radwanski says, “which is a nice feeling.”

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Foundation. All stories were produced independently by The Local.