When George was evicted from his basement apartment near Queen and Roncesvalles in December 2016, his anxiety and OCD went into overdrive. The apartment was a dump — poorly ventilated and moldy — but it was the only apartment he had ever lived in on his own, and at only $600 a month he knew it was a good deal. The owners said they wanted to renovate the units. The last he heard, they were being rented on Airbnb, where basement apartments in the neighbourhood go for as much as $95 a night.

George is over six-feet tall, but he walks slightly hunched over his cane. He’s 59, but his strained, raspy voice and thinning white hair make him seem a decade older. In addition to anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, he has cognitive impairment and chronic pain that he traces back to a traumatic brain injury he sustained when he was hit by a car as a child. George isn’t his real name. He’s afraid his neighbours or landlord will retaliate if they get wind of him complaining publicly about his living situation, so he asked to use a pseudonym.

When he was evicted, George began to panic. He didn’t own a computer and isn’t comfortable navigating the internet, so he couldn’t access Craigslist or the other online listings sites. He looked in the newspaper and called numbers on “For Rent” signs around Roncesvalles, where he grew up, but he quickly realized he’d have to focus his search south of Queen, in South Parkdale, where rents are cheaper. “I’ve always been a little afraid of Queen street,” says George. “I’d rather live closer to High Park. But on my fixed income, I couldn’t exactly be choosy.”

A couple weeks into his apartment search, while standing in line at a deli on Roncesvalles, a woman overheard George telling an acquaintance he was having trouble finding a place. She gave him a phone number, and when he called, the landlord said all he had available for his budget was a room in a rooming house in South Parkdale. He took it on the spot.

According to the Parkdale Rooming House Study, published in May 2017 by the Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust (PNLT), there are 198 rooming houses in Parkdale. They house 2,715 residents — more than double the number of Toronto Community Housing tenants in the area. In Parkdale, most rooming houses are converted Victorian homes, often run-down and poorly maintained, where four or more tenants share a kitchen and/or washroom while paying rent for their private room. George pays $600 a month for his 10 by 10 room with a shared bathroom. That eats up more than half of his Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) cheque.

For the neighbourhood’s low-income residents, rooming houses are often the last option before couch surfing, the street, or a shelter. But as prices skyrocket, with condo developers, real-estate speculators, and upper-middle-class professionals setting their sights on the neighbourhood as an “up and coming” place to invest, this last resort has begun to disappear. According to the PNLT study, 28 rooming houses have been lost in the past ten years, primarily to “upscaling” to market-rent apartments or conversions to single-family homes. Another 59 are at risk of disappearing.

When Victor Willis read the results of the rooming house study, it was sobering to see the hard numbers behind a crisis he’s watched unfold over the past several years. Willis is the executive director of the Parkdale Activity-Recreation Centre (PARC), a community hub on Queen Street that runs a drop-in centre, community meal program, supportive housing building, and a host of other services for residents living in poverty and experiencing mental health challenges. (PNLT’s offices are one of several community organizations with offices inside PARC’s main building and Willis is a founding member of the PNLT board of directors). “One of the things we realized with that study is that all of these private rooming houses are essentially paid for by public money already, since the majority of tenants are on some form of public assistance,” says Willis. But, if a private landlord decides to sell or renovate to attract wealthier tenants, all that de facto public investment in the building just disappears. “We thought, ‘There’s gotta be a better way,’” says Willis.

This year, instead of just helping residents deal with the fall out of disappearing rooming houses, PARC is taking one over. The organization has negotiated a long-term lease agreement with George’s landlord to turn his rooming house into supportive housing. The project is just one of the experiments local organizations like PARC are undertaking in an effort to buffer the neighbourhood’s existing low-income residents against massive demographic change. The affordable housing crisis has created a parallel public health crisis that directly impacts the mental, physical, and emotional health of Parkdale’s most vulnerable citizens. In response, the neighbourhood’s longstanding and diffuse network of social services organizations, community health institutions, and anti-poverty activists have been forced to find creative ways of working together to preserve the supply of decent, stable and affordable housing in Parkdale.

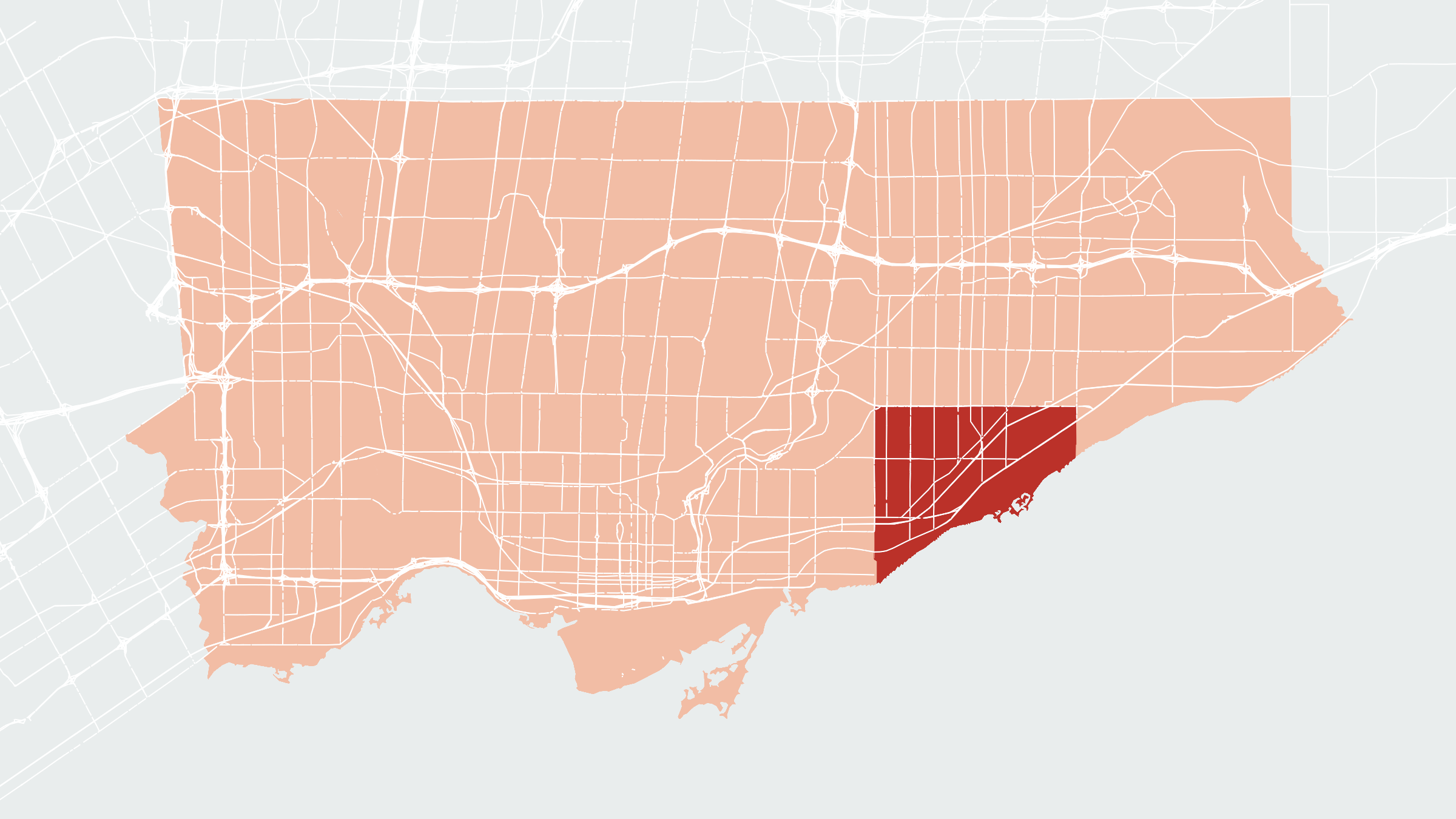

George is just one of about seven thousand low-income residents in South Parkdale, the area bounded by Queen St. to the north and Lake Ontario to the south, between Atlantic Ave to the east and the Humber river to the west. About a third of the population lives below the low-income measure, and one in five residents is on some form of social assistance. The neighbourhood has the second highest rate of emergency department visits in the city as well as the second highest rate of hospitalizations for mental health and ambulatory care sensitive conditions (an umbrella term that includes diabetes, asthma, hypertension, among other chronic diseases where effective community care and case management can help prevent the need for hospital admission). For residents like George with mental health challenges, reduced mobility, and chronic illness, a bug-infested room in a neglected and run-down rooming house is better than spending nights in a crowded shelter or on the street, but these sub-standard living conditions still have serious health implications.

Jane Rajah, a diabetes nurse educator who has worked at Parkdale Community Health Centre for more than a decade, says that residents living in unsanitary, unsafe, and unstable housing situations are often at higher risk for amputation, blindness, and other diabetes-related complications. They have high rates of hospital admission, heart attacks, smoking, drug use, and early death. And the fear of eviction and other stresses related to inadequate housing and social isolation can worsen the symptoms of residents living with mental health conditions and addiction issues. “If I put myself in the shoes of our clients getting served eviction notices, I would be terrified,” says Rajah.

With most shelters in the city at capacity and a very low vacancy rate in the neighbourhood, an eviction can mean ending up on the street, a result that can be especially disastrous for residents living with mental illness and addiction issues.

Willis says that since all of the residents in George’s current building are already on ODSP, one of PARC’s main goals in taking over management of the building is to provide the residents with better access to support services. PARC already runs its own supportive housing for residents with a history of mental health conditions and addiction, and Willis has seen firsthand the dramatic improvements in resident’s health and wellbeing once they are in housing that is stable, with a dedicated support worker to help them get to medical appointments and access social services. “Even people with complicated health issues can live independently, but the right supports have to be in place,” he says.

Taking over George’s building is the first step in PARC’s plan to add 60 units of supportive housing over the next three years. PARC has negotiated with the landlord to take over the maintenance of the rooms and living spaces, and do some basic renovations to bring the buildings up to a more decent standard of living. It will also manage the rent-geared-to-income tenancy and provide a full-time support worker assigned to the building. The landlord will get a guaranteed lump sum monthly rent payment from PARC (partially paid for by public housing subsidies), and will only be responsible for making sure the utilities are working and the physical structure of the property is safe and in good repair. The hope is that this kind of long-term agreement will lower the landlord’s incentive to sell, but Willis is also negotiating to get the right of first refusal into the agreement so that PARC, in partnership with PNLT, would have the option of buying the building down the road.

Working in privately-owned rooming houses is a first for PARC, but other organizations in the neighbourhood have been running similar programs for years, with encouraging results. More than ten years ago, Rajah and a dietician at the Parkdale Community Health Centre worked in partnership with Habitat Services and COTA, another community-based organization serving adults with mental health challenges, to develop a mental health and diabetes-focused support program for the 10 residents of Bailey House, a privately-owned boarding home in Parkdale (a boarding home is similar to a rooming house, but offers daily meals as well as a room). By bringing in a small team of full-time support workers trained to support clients with mental illness and diabetes, a cook to offer healthier meals, and in-home medical visits for residents, Rajah says they have seen significant improvements in clients’ blood glucose levels, improved eating habits and fewer emergency room visits. “Rates of diabetes in this population are very high, and in my experience in Parkdale, emergency room visits for severe hypoglycemia are extremely common,” says Rajah. Based on the success of Bailey House, Rajah and her community partners are working to expand the program to 18 other boarding homes in the area.

Although she is excited about the potential of expanding supports to other residents in the neighbourhood, Rajah still worries about the overall reduction of affordable housing options in the neighbourhood. “My biggest fear is still what happens if we lose more boarding homes and rooming houses,” says Rajah. In the past few years she has seen several homes sold out from under low-income tenants. With most shelters in the city at capacity and a very low vacancy rate in the neighbourhood, an eviction can mean ending up on the street, a result that can be especially disastrous for residents living with mental illness and addiction issues. In March 2017, the community mourned the loss of beloved local resident Navneet “Nav” Sondhi, who died a week after being evicted from a rest home on Callender Street.

Even the fear of ending up on the street can have serious health consequences. Paul Snider was among the 27 tenants of the former Queen’s Hotel who were evicted illegally on short notice in the summer of 2015. Snider is 43 and lives with major depressive disorder, anxiety, and PTSD. He remembers spiraling into a state of “anxiety and dread” when he realized he had to find a place within a matter of days. With the help of a social worker, he ended up finding a room in a notoriously squalid rooming house only days before he had to be out, but he watched his close friends and neighbours end up on couches, in tents, or on the street. “My room is infested with all manner of bugs, and if I’m going to be objective it is absolutely unacceptable as a living space,” says Snider. “But I’m so freaking grateful to these slum lords for putting me up, no questions asked.”

Snider knows he might be able to find a nicer place for the same price in a different area of the city, but the stress of moving again is too much to bear. “Parkdale is the only place I’ve ever felt even close to fitting in and having a real community,” says Snider, who used to live in the east end of the city before moving to Parkdale four years ago. “I actually have friends here and my mental health has improved a lot since I moved here.”

Pete’s Corner Grill, at the corner of Queen Street West and Sorauren Avenue, is one of the last remaining greasy spoon diners in Parkdale. In a neighbourhood where a new brunch spot serving $15 eggs benedict and $5 lattes seems to pop up every month or so, at Pete’s there’s still only one kind of coffee and you can get a hearty 3-egg breakfast for under $7. It’s on the same block as PARC, the Parkdale Community Food Bank, and a Money Mart, and it serves as a meeting place for many low-income residents in the neighbourhood.

I meet George at a table in the corner on a sunny afternoon in November. He’s clean shaven and wears a button-down shirt and fleece vest. He stands up to shake my hand, and winces in pain as he raises from his chair. He has chronic back issues and he finds it increasingly hard to sit upright for more than a few minutes. “I hate where I live now,” says George. “But on my fixed income, what choice do I have?”

After we finish our lunch at Pete’s, George gets the rest of his bacon cheeseburger to go and we head out to meet Omid Zareian, a housing support worker from PARC. George wants Zareian to help him find a new apartment, but first Zareian wants to see his current place — his first look inside the building PARC plans to take over in a matter of months.

George’s place is in a semi-detached three-story Victorian home, a dilapidated version of the kinds of homes that go for $2 million in this area once they’ve been renovated. He leads us inside, and we climb a flight of narrow stairs covered in a patchwork of stained, thin grey carpeting. The walls are scuffed and roughly patched. George pauses for a moment on the landing halfway up to the second floor to catch his breath and then steadies himself with his cane and slowly climbs the final few stairs. What passes for a kitchen is not much more than a narrow walkway between the hallway and the bathroom, with a sink, four-burner electric stove, and about two square feet of counter space. The bathroom — the only one on this floor — is a single toilet wedged between a tiny sink and a grime-covered shower in the corner.

Zareian shakes his head in disgust. “Just think of all the money these landlords are pulling in,” he mutters under his breath. “What a disgrace.”

George’s room is jammed with his possessions. Boxes and plastic bins piled shoulder-high line every wall of the room, leaving only a two-foot-wide path from the door to the side of the bed. “This is my whole life in here,” says George. There are cans of insect repellent and roach traps on the floor. George is currently dealing with a bedbug infestation. “Not exactly ideal when you have OCD,” he says. A framed photo of his mother in her wedding dress sits atop one of the tallest piles of boxes beside his single bed.

“To hear people say, ‘Why don’t you just move them to a cheaper market?’ is shocking to me. These are human beings.”

George is desperate to move to somewhere on the ground floor with his own bathroom. He has trouble climbing the stairs and needs to ask for help from neighbours to carry his groceries and laundry. And he’s kept up at night by the bedbugs and the noise of other tenants cooking and playing loud music into the early morning.

Zareian tells George it might be worth trying to a hold out a few more months to see if things improve once PARC takes over. “Maybe we could get you onto the ground floor once we’re in here,” says Zareian. Before he leaves, Zareian makes an appointment with George to discuss his options, which will include making sure he’s on waiting lists for seniors’ and long-term care housing.

As Zareian and I walk up George’s street toward Queen, he tells me it will be next to impossible for George to find anything better in the neighbourhood on his budget. “Honestly, compared to some places I’ve seen, that place is a palace,” says Zareian. “But it isn’t just about the physical space, it’s about the support people need to not become totally isolated.” This is why Zareian encouraged George to stay at least until PARC takes over. If he moves somewhere else, he’ll still be on his own.

Once PARC takes over this rooming house, and others in the future, Willis’s hope is that the residents will become more connected to the greater community. The organization has spent 38 years developing programs and supports for people living with mental health challenges, so at this point there is what Willis calls an “economy of proximity” to keeping people who need those services in place. “People living in those houses can walk up here to PARC and get a meal seven days a week and we have all kinds of programs and activities here,” says Willis. From the foodbank downstairs to counselling services to the social enterprise painting business that trains and employs community members, PARC can serve as the hub that connects tenants of rooming houses to the supports they need to improve their overall health and wellbeing.

Over his 18 years at PARC, Willis has heard many people suggest that if low-income residents can’t afford the neighbourhood, maybe they should just move on — head out to the inner suburbs where rent is cheaper. But PARC’s working premise is to keep people where they are, where they have established relationships, and where they already have health care providers and support networks. “It’s based on the simple understanding that these are people who may have been here their whole lives,” says Willis. “To hear people say, ‘Why don’t you just move them to a cheaper market?’ is shocking to me. These are human beings.”

For George, as much as he dislikes his current living arrangement, he isn’t interested in leaving the neighbourhood. He recently went to see a bachelor apartment at Keele and St. Clair, but the thought of moving that far away just wasn’t worth the trade-off. George has fond memories of walking up Roncesvalles with his mother who would chat in Polish with shopkeepers and acquaintances along the way. He spent his childhood in High Park and at Sunnyside Pool. “I remember when I was young, walking through the park in the fresh snow at night, with the moon shining. It was just beautiful,” recalls George. On days when he has the energy, he still goes for walks in the park, and when the leaves are off the trees in winter, he can see Lake Ontario from his second-floor window. “The lake, and the park and this whole neighbourhood — it’s home,” says George. “I just want to grow old and die where I was born. That doesn’t seem like too much to ask.”