Every weekday morning, Rosemary Carreiro leaves her house by 6:45 a.m. In winter, it’s still dark as she walks along the icy sidewalks of her Yorkdale-Glen Park neighbourhood to catch the bus heading south to visit her first clients of the day in Little Portugal, near Dufferin and Dundas.

Carreiro is fifty-four years old and works as a homecare personal support worker. She’s always drawn a clear line between her family life and her professional life and keeps the difficult details of the job from her husband and two sons, now 17 and 23. “Other people talk about their jobs around the dinner table,” says Carreiro. “But there’s nothing good to say about it. Even if a client dies, my kids would never know. I don’t mention it.”

For more than ten years, Carreiro has started most workdays caring for the same elderly Portuguese couple, now in their 90s. She gets them up for the day, gives them sponge baths, dresses them, and patiently spoon-feeds them breakfast in bed. As soon as she’s done, she hops back on the TTC or speed-walks to her next client. She doesn’t have time to linger. The homecare agency she works for pays travel time by the kilometer and expects her to calculate the fastest possible route between visits.

Carreiro will make six more home-visits before she gets back on the Dufferin bus around 6 p.m. She tries to pack in as many clients as the agency will give her; any breaks or downtime are unpaid. Carreiro could try to build up a roster of clients closer to home to cut down on her commuting time and shorten her 12-hour days. But as a Portuguese-speaker who immigrated from Brazil, she is in high demand in Little Portugal, and she doesn’t want to leave her longtime clients. After twenty years in the job, Carreiro makes $19 an hour, the maximum wage for a publicly funded PSW in Ontario. “I love my job, but a lot of people don’t want to do it because it isn’t seen as important and the pay is not good,” she says.

According to the Ontario government, homecare workers like Carreiro represent the future of primary health care. As part of the government’s pledge to “end hallway medicine” and reduce waitlists for long-term care beds and overcrowding in hospitals, the 2019 Ontario Budget includes $267 million in new funding for “home and community care.”

Providing care to people in their homes can improve their health outcomes and keep them from showing up in overcrowded hospitals. It also saves money, as personal support workers with part-time, on-call positions make far less than other health care workers.

As our population ages, homecare personal support workers are poised to become an increasingly critical piece of our health care system, but they aren’t compensated, respected, or regulated in the same way as other health care professionals. And in a city with rapidly rising rents and costs of living, the workers caring for Toronto’s most vulnerable residents are barely making enough to get by.

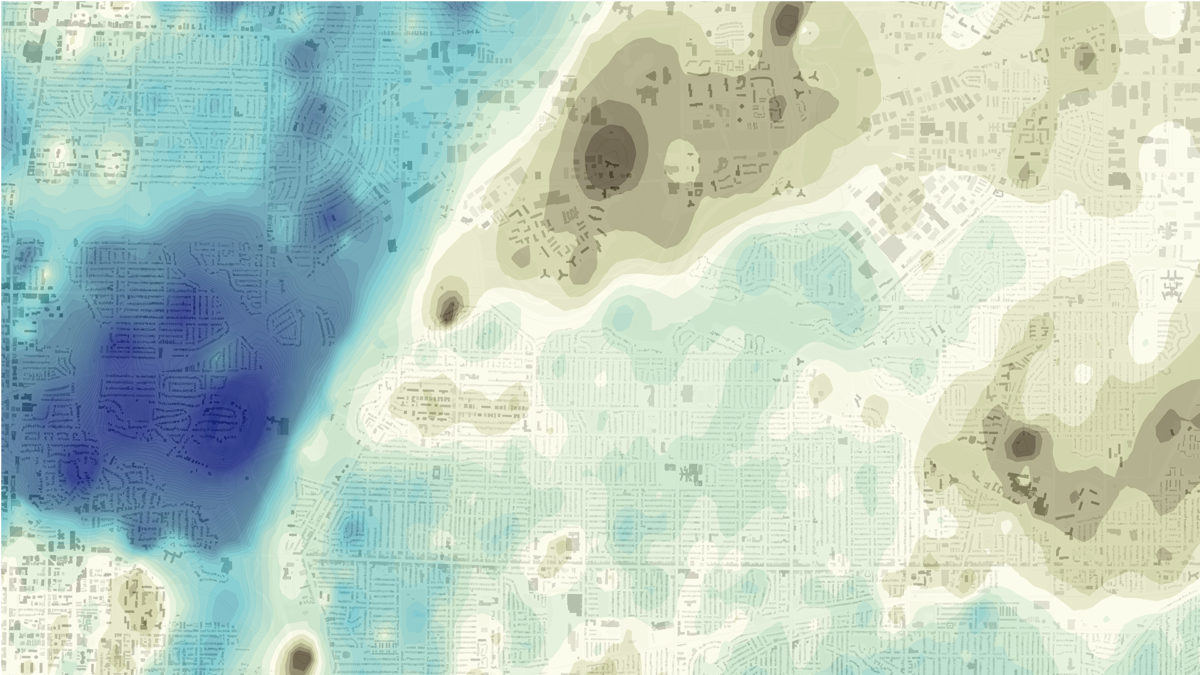

According to a 2015 report by John Stapleton for the Metcalf Foundation, nine percent of Toronto’s working population are members of the working poor (workers earning below the low-income threshold). Despite booming economic growth, Toronto is home to the highest concentration of working poor in the country, a group that includes many of the city’s PSWs. Stapleton points to the rise of part-time, contract, and temporary jobs with irregular schedules as a key factor that prevents so many of the city’s workers from earning a living wage. And as rents in the core of the city continue to rise, the concentration of working poor residents has decreased downtown while it has increased in areas in the northern parts of the city.

Norma Varone works at the same agency as Carreiro. She’s a single mom who has been working as a PSW for 17 years and still lives cheque to cheque. Varone lives downtown in a rent-geared-to-income Toronto Community Housing building where she pays just over half the average Toronto market rent for the two-bedroom apartment she shares with her teenage daughter. “If I didn’t have this place, I’d probably have to move way up north of the city to find a home I could afford,” she says.

“PSWs are going into homes supplying the most important personal care for individuals, and many are making below the poverty line”

Varone is currently working shifts as a receptionist in the agency office after she slipped and fell on an icy sidewalk on the job in December 2018. Before her injury, she was working up to seven days a week, taking extra hours on the weekend whenever she could. After rent, utilities, cellphones, and groceries each month, there often isn’t much left for anything else. School trips and monthly TTC passes usually don’t make the cut. When she started her job in the office earlier this year, she realized she didn’t have any appropriate clothing, so she went clothes shopping for herself for the first time in ten years.

“PSWs are going into homes supplying the most important personal care for individuals, and many are making below the poverty line,” says Miranda Ferrier, a former PSW and the president of the Ontario Personal Support Workers Association. Even the most experienced, highest-paid homecare PSWs are barely clearing the threshold for what is officially considered “low-income” in Canada ($33,252 after tax for a family of two in 2017).

In 2015, the Ministry of Health and Longterm Care estimated there were about 100,000 PSWs across the province, with about a third working in homecare. A 2015 survey of PSWs in Ontario by researchers at McMaster University found that 94 percent were women, 69 percent were aged 45 or older, and 41 percent were not born in Canada.

Ferrier says if the provincial government wants homecare to be a major part of the solution to overcrowding in hospitals and long-term care waitlists, they need to make the job more attractive and more sustainable. In a 2018 survey of her association’s members, about one in six said they were thinking of leaving the profession, citing burnout, inadequate pay, and injury as their top reasons for leaving. “We are losing PSWs every quarter to Tim Hortons, factory work, housekeeping, you name it,” says Ferrier. “We need to make this a profession of choice.”

Low wages and unreliable hours have led to a province-wide shortage of PSWs, says Sue Vanderbent, the CEO of Home Care Ontario, the association that represents the agencies that are contracted by the provincial government to provide homecare services. Vanderbent says that, compared to the current crisis situation in some regions of the province, it is somewhat easier to recruit new PSWs in urban areas like Toronto where newcomers provide a steady stream of new entrants as other PSWs burn out and look for other work. “People are drawn to this job because they want to care for people, and it should be a good job,” says Vanderbent. “But if we want to keep PSWs in the long run, and if we want to tip the scales toward keeping people in their homes and out of emergency rooms, the government needs to invest in higher wages and more hours of care per client.”

On top of the unpredictable hours and low pay, PSWs often face difficult working conditions. “When you’re going alone to work in someone’s home, you don’t know what’s going to happen,” says Carreiro. Verbal abuse and harassment are a regular part of the job. Carreiro says she feels lucky that she’s never been physically attacked by a client, although once a client’s wife threw a glass tumbler at her, narrowly missing her head. “When something like that happens, you just have to walk straight out the door,” says Carreiro. But because PSWs are paid per client there is an incentive to put up with milder forms of abuse and harassment or risk losing that income.

Many PSWs also struggle with the emotional burden of caring for clients who are at the end of their lives. Carreiro says she will never forget the first-time a client died while she was in their home: “To see someone die right there in front of your eyes, it takes a while to get it out of your head.”

She says it is hard to just move on to the next client after a death, but since losing a client also means immediately losing a portion of her income, she has no choice but to try to push it out of her mind and keep working. “It’s so hard because, to me, they’re not just a paycheque,” says Carreiro. “These are people I care for—I truly care for them.”

Ferrier, Carreiro, and Varone all say they wish more people understood how much PSWs love their work. “I always say that it takes someone truly special to be a PSW,” says Ferrier.

For Carreiro and Varone, working as a PSW is not a job of last resort. It is a privilege, a calling even. Carreiro knows she could make more money doing something else, but PSWs “don’t work only for money; we work with our heart.” She just wants her skills and expertise to be fairly compensated, and for the politicians who keep publicly touting the importance of homecare to invest in the women like her already doing the work.