“Okay, Mom, come in front, Mom. And Kevin, back up a half a step and turn towards your sister.”

It’s the first Sunday afternoon of 2020, overcast and frigid, and Rodrigo Moreno bobs and weaves around the front lawn of this semi-detached public housing unit, trying to get a portrait of this multi-generational family bundled up in their winter coats. He directs the Jamaican-Canadian family’s movements in a way that’s warm yet firm, and they follow—trusting him to capture their essence, this moment in time.

“I have good memories with you all, I’ve followed you around for a while,” he says, crouching before the smiling family, who laugh together as the camera shutter clicks. “I’ve got some good pictures of you, man, you have to see.”

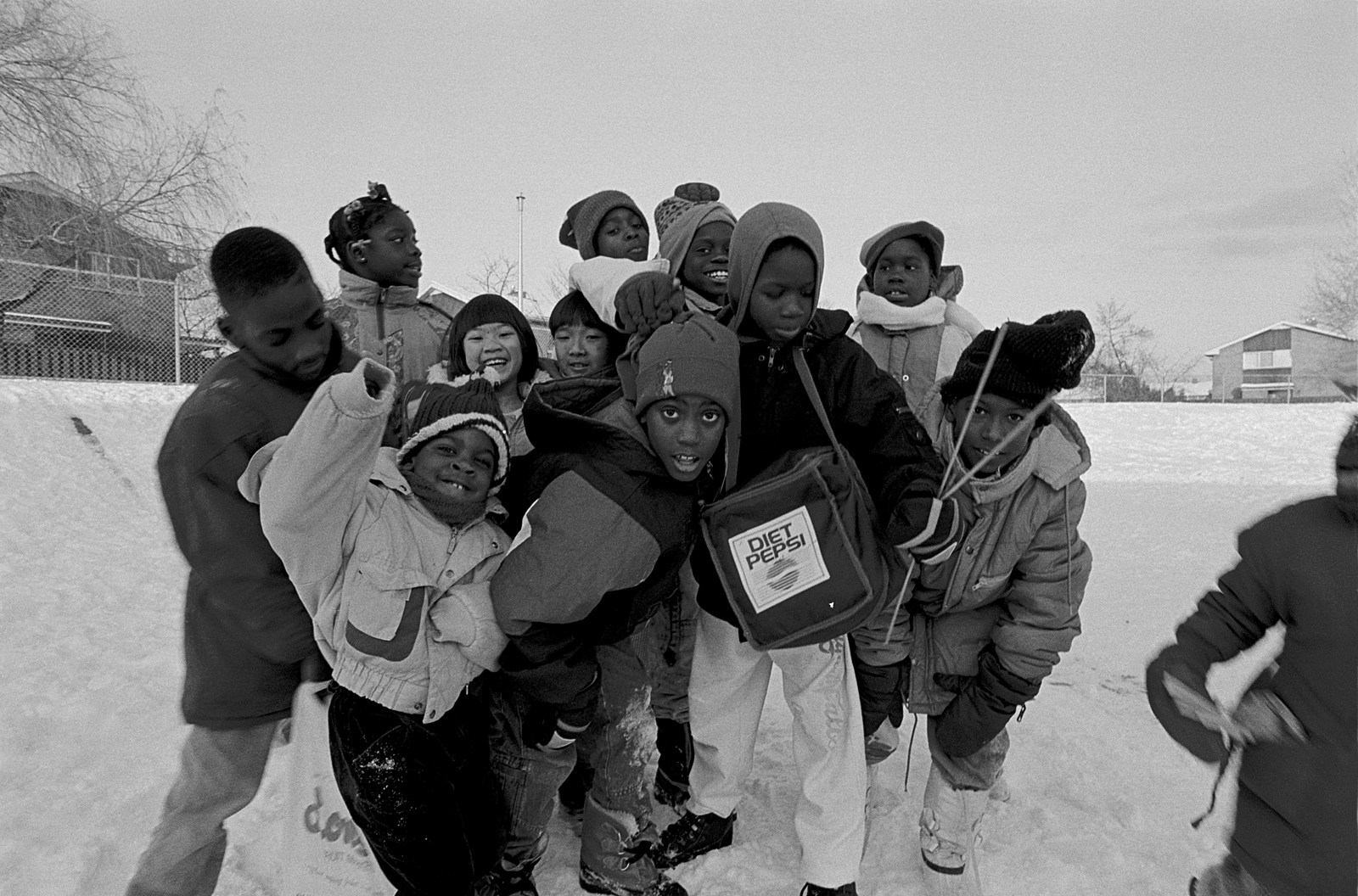

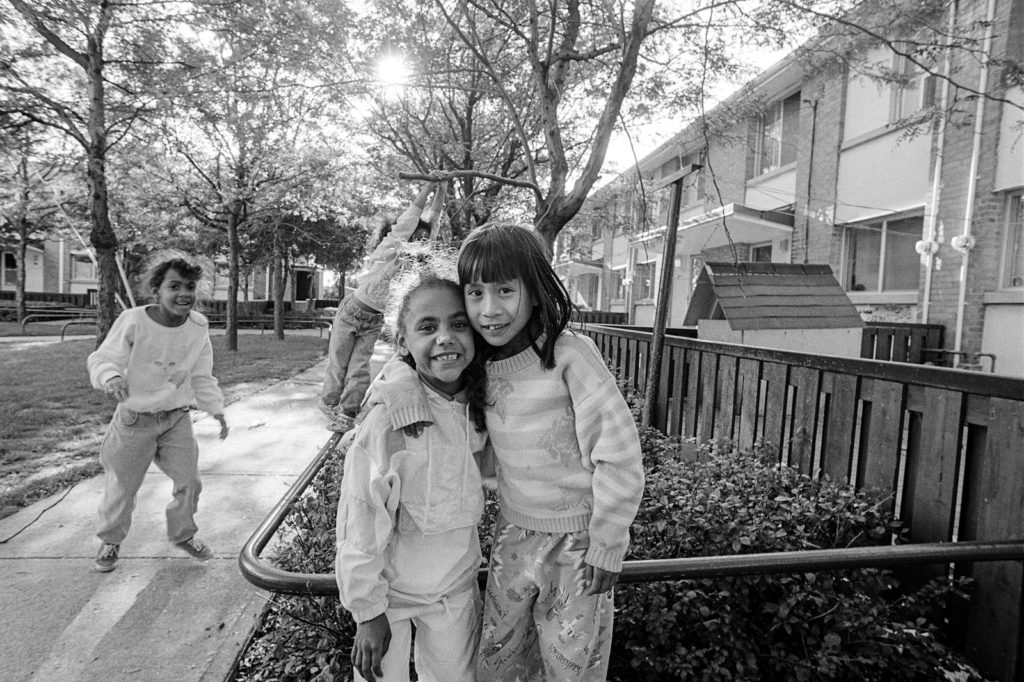

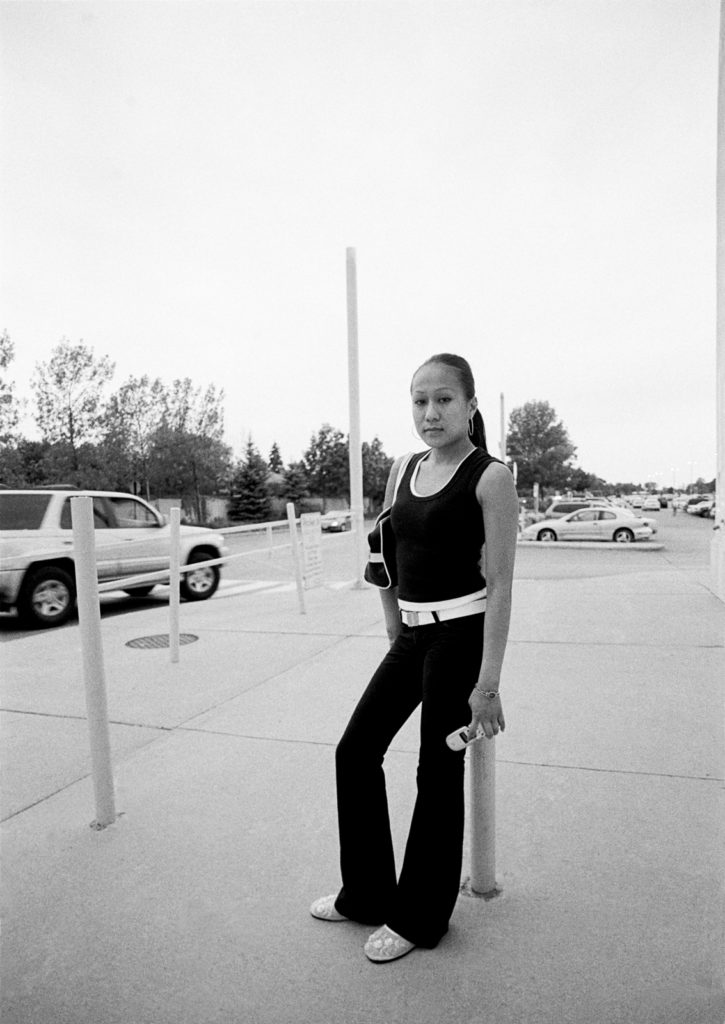

Over nearly three decades, Moreno, 51, has documented life in Lawrence Heights—a place he called home for his own formative years—producing stunning black and white photos that have become an invaluable Seven-Up-style time capsule of a community typically portrayed under headlines about crime and violence. One of the first portraits he ever shot bore the beaming, mischievous face of seven-year-old Alicia. He photographed her again in 2004 when she was 18, bearing that same smile and a ponytail with her arm slung around her little sister. Now he’s back for the third installment of his series, shooting the beautiful 35-year-old, her own 12-year-old son looking nearly identical to her younger self standing by her side. Alicia and her family talk and joke with Moreno like he’s an old friend, which he kind of is, having entered and re-entered their lives through the years to take their portraits. The Picture Man.

The family has lived in Lawrence Heights since 1988, but today is the last time they’ll gather on this front lawn for a shoot with Moreno. Their days in this home are numbered. The Lawrence Heights revitalization project, which started in October 2015, has finally reached their doorstep. The people in units on either side of them have already moved out, their windows boarded up. The family matriarch, Jean (who Rodrigo and everyone else affectionately call her Mama J), hopes to be moved into a unit in the highrise that swallows the skyline at the end of their street. The rooms are smaller there, and there is no basement, but space in a fresh, modern building would be a welcome change.

Moreno understands the need to preserve the memory of this place. His childhood home on Bagot Court, just a few streets over, is already flattened, erased with the swing of a wrecking ball this summer before he could stop by and take one last photo. There’s an underlying urgency in his voice as he directs this family’s final portrait here. The afternoon light is fading. Time is running out.

It was a photograph that brought Rodrigo Moreno across a continent and home to Lawrence Heights. He was born in Chile, where his father, a politically active teacher, helped democratic socialist leader Salvador Allende win power in 1970. But the 1973 coup d’état meant the Morenos were no longer safe, even in their idyllic suburban life. Moreno’s dad tried multiple times to convince the Canadian consulate to let them emigrate to Canada. On the third or fourth attempt, he brought a family portrait. According to Moreno lore, the bureaucrat was so moved by the image of the family together he let them go.

The mother and father, two daughters, and two sons arrived in Toronto on Christmas Eve, 1974, first settling in an apartment at College and Euclid. Moreno was six. Moreno’s dad found work welding furniture parts together, and after two years the family moved out to Lawrence Heights—a relatively new housing development surrounded by expansive green fields where the kids could play their beloved soccer. “It was a really, really vibrant community, tons of energy, tons of kids,” he says. “It was a fun place to grow up.”

At 16, Moreno started hanging with a group of guys who satisfied his need to rebel. They were kids, he says, who didn’t have a lot of support at home. They were living in poverty, supported only by single mothers, with no father figures and no curfew like he had (which he feared made him desperately uncool). One night, Moreno agreed to keep watch while his friends broke into a sporting goods store’s display case at Yorkdale Mall and stole bicycle parts. They were busted by the cops and Moreno was charged with breaking and entering and possession of stolen goods. Seeing his mother cry—realizing that he was capable of causing her pain—was the turning point for him. “That, to me, left a really big imprint. I knew I had to change things.”

He quit hanging around those friends and turned his interest toward photography. He eventually moved out and got a day job at Grand & Toy’s head office, where his aunt worked, and took photography classes at Ryerson at night. His first photos of Lawrence Heights—visceral and incredibly real photos of life in the public housing neighbourhood—were practice shots for his documentary photography class at Ryerson. His instructors were impressed. Moreno went on to carve out a career for himself as a professional photographer, shooting products and people. In 2001, while living downtown, he learned about revitalization plans for nearby Regent Park and heard that Lawrence Heights was next. His family had since moved away, but he knew he had to return with his camera. Maybe he could even follow up with some of the people he’d photographed nearly a decade before.

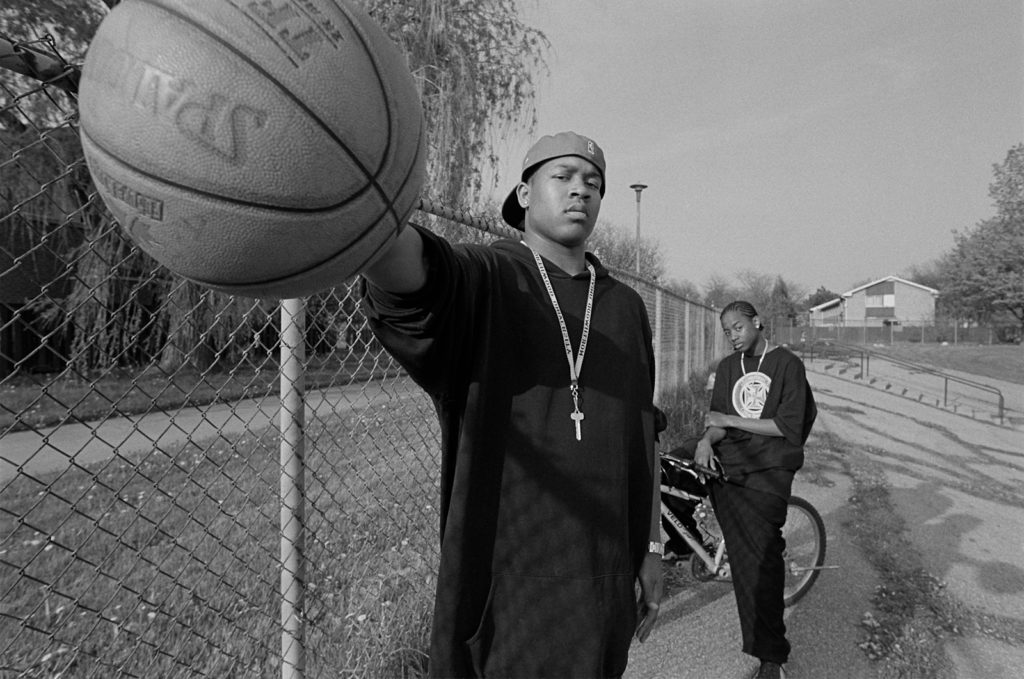

Moreno returned to Lawrence Heights with a few contact sheets—tiny prints of the negatives from his old-fashioned camera. The neighbourhood had changed over the past decade—still as tight knit as he remembered, but getting a little poorer, a little more vulnerable to crime. The neighbourhood’s moniker the “Jungle” was now being used in media reports in reference to growing gang violence. Moreno wanted to return not only to document the community he grew up in before it was transformed by the revitalization, but to see if he could make a difference for young people at a crossroads.

It had been a few years since he’d been back, so he remembers feeling nervous as he approached a group of teenage boys hanging out on a crescent. He clutched his contact sheet and asked them if they knew any of the kids in the photos.

Turns out, it was them.

“They started laughing and making fun of each other, like “Look, what were you wearing [back then?]” he says. In a community in which trust is hard won, Moreno instantly fit back in. He shot what would become his second series of photographs of life in Lawrence Heights—photos of young men mugging for the camera, a brother protectively hugging his younger sister. He went back to find Alicia, who was now 18 and took photos of her and her younger sister, Felicia, at the top of Cather Crescent. When he takes these photographs, “there’s no border between us,” he says. “There’s no wall, there’s just who they really, really are.” By 2004, he had completed another series.

Moreno began to understand the impact of documenting this neighbourhood, which had become so deeply misunderstood by politicians and the wider public. It meant something to the people there that he cared about their lives, the lens of a professional camera turned their way a reminder of their potential, their value. He started the Shades Photography Club for youth, which helped get young people interested in the craft and storytelling of taking pictures. It gave them something fulfilling to do. In 2005, they hosted a gallery expedition—Silence the Violence—at the North York Civic Centre. Former student and photography club member, Taejan Cupid, remembers the way Moreno invited him into later iterations of the club and drew out his nascent interest in photography. The 20-year-old now runs his own event photography business and is here on this January day helping Moreno document this project. His family has since left for Brampton after his brother was shot in a drive-by in 2013. “It’s great to see that they’re revitalizing, but deep down I wish it could just stay the way it was,” says Cupid. “All those memories are entombed and time-capsuled into what’s here right now.” Moreno’s photos, at least, will live on.

Earlier this summer, Moreno brought his son to visit the site of his old family home on Bagot Court. He took a rock as a memento—just something to keep. He now lives in Midland, Ontario, with his family, his own version of his parents’ hunger for wide open spaces taking him up the northbound highway out of town. But he finds himself returning time and again. “I always drive through here. People who lived here, there’s a tendency to always come back. It’s like coming back to the scene of the crime,” he says with a laugh. “I think [we do it because of] the dear memories we have. This was a great place to grow up and people share those memories with each other.”

Lawrence Heights, Alicia says, is in their DNA. While Mama J awaits word on whether she’ll be moved to the condo at the end of a street, a townhouse, or elsewhere in the revitalized community, the family is hoping for the best but knows no redevelopment construction project could ever really uproot them.

“We’re like family living here. You hurt one, you hurt everybody,” Mama J says. “Now, we don’t really know what’s going on, but in the days coming up to now, we live as one.”

While Mama J and her daughters are still gathered after the group shots, Moreno tells them about another photographer in Buffalo, New York, whom people had been comparing him to for years but whose work he’d never seen. Eventually, he met Milton Rogovin, who shot the photo series The Forgotten Ones. “He always said, and it stuck with me, that the rich have their own photographers, so what do the poor get?” he says to them. “We get unnoticed or moved from place to place. My dedication has to be to the people who are not, supposedly, important and show how important they really are.”

As the light fades to black, Moreno has whittled the group down to Alicia—one of the rare subjects he’s been able to return to over these past three decades. She looks into the camera with the same fire in her eyes that flickered there when she was seven years old. She vogues and mugs a bit, having fun but also understanding the lasting value of photos like these.

“I can’t even articulate what it means, how it feels,” she says. “It’s surreal just to see [a project] like this and for him to continue to do it. He’s dedicated to us and the community.

“Some people would’ve forgotten about us.”

Rodrigo has not.