“I’m sorry, if they can put trees on top of buildings, they can put trees across the Allen.”

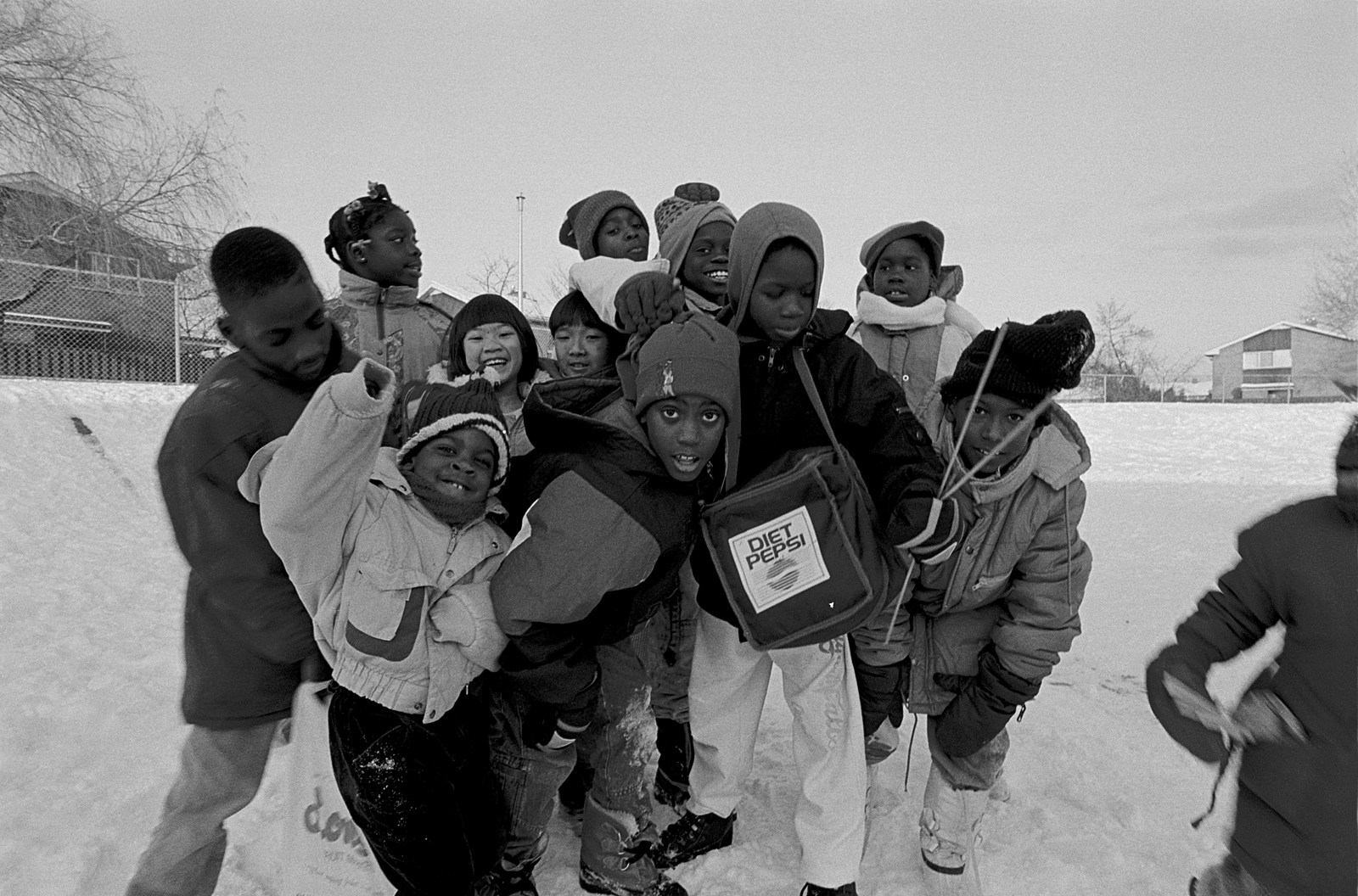

Denise Bishop-Earle was standing on Varna Drive in the northeast corner of Lawrence Heights one overcast afternoon this winter, looking at the first phase of the neighbourhood’s redevelopment. The empty space where buildings had once been provided panoramic views of the two new large residential buildings flanking Allen Road, like a northern gateway to the neighbourhood. The towers had the effect of minimizing the highway, so it no longer dominated the landscape as it once did. It was still there, though, its dull roar sounding like the white noise of ocean surf, if you used your imagination.

“You can hear the cars speeding on it sometimes,” said Bishop-Earle, a resident of the community for the last thirty-five years. “Oh, somebody’s racing someone else down the highway. You can hear all the noises.” Bishop-Earle was musing about what to do about the road that cuts her community in two. What if it disappeared under a park? “It would buffer the noise. They have sound barriers now but they don’t really do anything. Then there’s the dust and the dirt that ends up on all these windows.”

Talking about what to do about Allen Road, an expressway in all but name, has been a Toronto tradition for generations. When it was proposed and planned throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Spadina Expressway, as the project was then called, was to be part of a network of limited access highways in Toronto. The Spadina leg would have begun just north of Highway 401 and run south to Lawrence and then Eglinton Avenues, after which it would take a diagonal route through Cedarvale and Nordheimer ravines to Casa Loma, where it would continue straight south down Spadina, finally expelling high volumes of traffic in Chinatown and Kensington Market.

The section south of Casa Loma would have passed through the Annex, a Toronto neighbourhood of considerable political and cultural clout, filled with just the kind of university professors, lawyers, and media-savvy sorts who could mount a campaign to stop a freeway, even if it was already under construction and advancing towards the city centre.

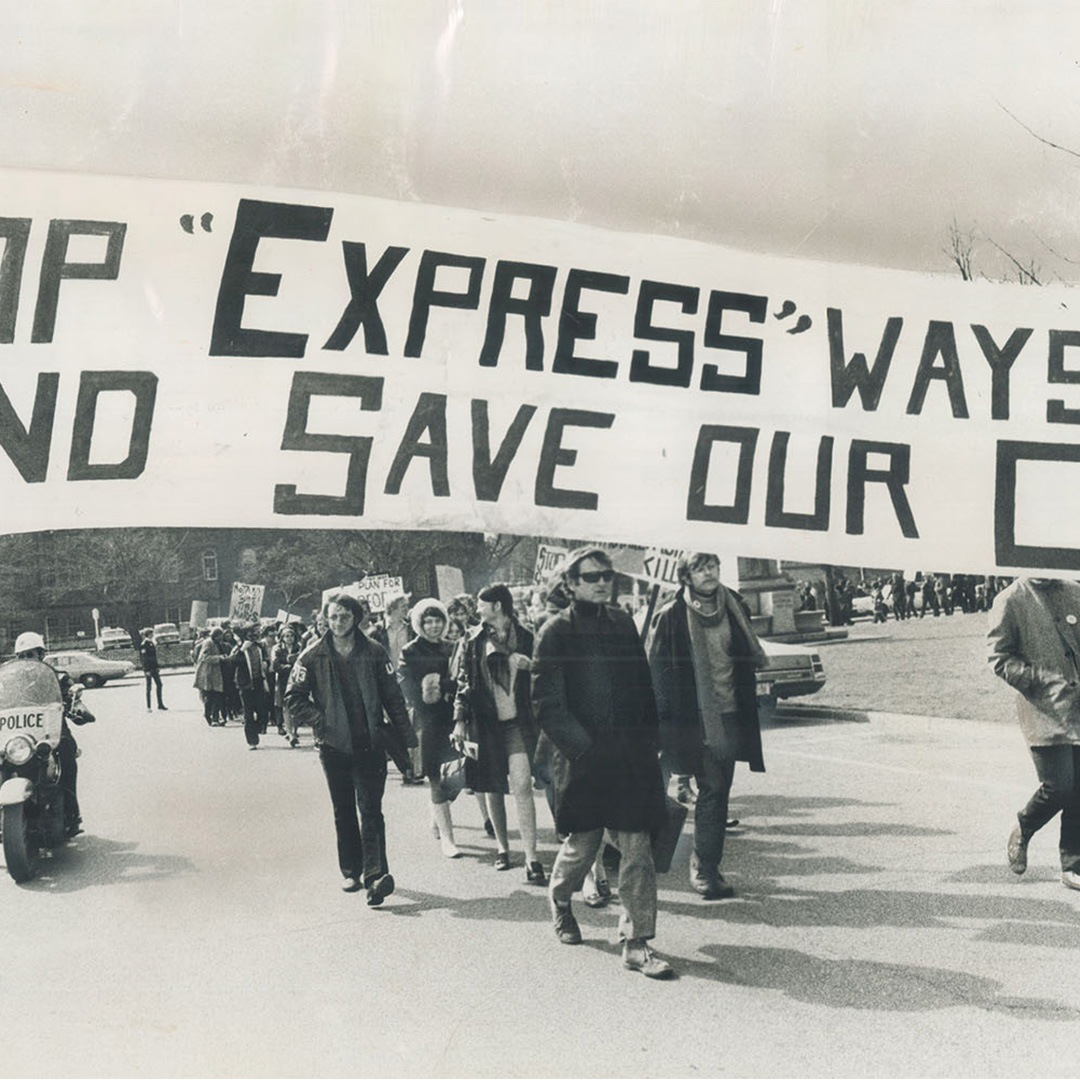

The drama and rhetoric around the fight was intense. The famed urban thinker, writer, and activist Jane Jacobs, who had recently moved to Toronto from New York, joined the fight, fresh off her victorious battle against Robert Moses and his Lower Manhattan Expressway. The Bad Trip: The Untold Story of the Spadina Expressway, published in 1970 by David and Nadine Nowlan (two of those savvy Annex sorts) includes an opening blurb by Toronto resident Marshall McLuhan. “Citizens of Toronto, reach for your Cass-masks,” he wrote, referencing transportation engineer Sam Cass, Toronto’s version of Robert Moses. “Get ready for the world’s most supercolossal car-sophagus—right here on old Bloor Street. Toronto will commit suicide if it plunges the Spadina Expressway into its heart.”

In 1971, as construction was set to advance south of Eglinton, then-Premier Bill Davis halted the expressway there at the eleventh hour. “If we are building a transportation system to serve the automobile, the Spadina Expressway would be a good place to start,” he declared in the Ontario legislature. “But if we are building a transportation system to serve the people, the Spadina Expressway would be a good place to stop.”

The “Stop Spadina” movement is a story told and retold in Toronto. It’s a feat people in few other cities in North America were able to pull off, perhaps one of the greatest symbols of citizen resistance to top-down, mid-century planning. The mythology around the victory is so strong it makes it seem like once Davis’s cabinet proclamation took place, all was well in the land. And indeed it was for a large part of the central city. For over fifty years, however, the Lawrence Heights neighbourhood has lived with a freeway running through its heart, an ongoing story not often told that continues to have a profound effect on the community.

In a series of aerial photographs at the Toronto Archives, you can trace the evolution of Lawrence Heights and the freeway that divides it. In 1956, the area where the neighbourhood would eventually be located still bore traces of the farmland that existed just a few years prior. Where the Allen would eventually be located, a dirt or loosely paved road stretched from Lawrence to Ranee Avenue, the latter already sporadically lined with houses. Jump forward four years and Lawrence Heights is under construction, its circuitous road pattern laid out, the words “Spadina Extension” written on the photo’s centre road to indicate where it would go. In 1962, the neighbourhood was complete, with space in the middle for the eventual highway, and by 1966 the highway was completed from Lawrence Avenue north to what would be called a “super exchange” where it meets the 401 next to the brand new Yorkdale Mall.

South of Lawrence, a tight grid of residential houses that had already been developed were expropriated and razed. Three hundred homes were destroyed in this more affluent neighbourhood. But of the eight streets that once crossed the highway’s right of way, seven overpasses were built to replicate the connections. In the public housing project of Lawrence Heights, just two crossings were built—the expressway effectively slicing the community in half.

“A lot of my friends were on my side of the highway,” remembers André Darmanin. “I hardly ever crossed to the other side of the highway unless I was going to school. For utilitarian purposes I would go over there, but it was a barrier for a lot of social activities.” Darmanin grew up on Leila Lane, in a now-demolished apartment adjacent to the highway on the east side, and lived in the community from 1972 until 2000. Trained as a planner himself, he’s gone back to the neighbourhood on occasion to observe the place he grew up in and recall some of its patterns. “People travelled in north and south directions in the neighbourhood,” he says. “You’re going north to Yorkdale Mall or its subway station or you’re going south to Lawrence West station or Lawrence Square. You never really go east or west.”

The divide created by the highway produced its own mythology over time, with the west side known as “America” while the east side was termed “Canada.” “It’s the American side because there’s no resources, basically,” says Bishop-Earle. “There’s only townhouses and a few apartment buildings. Whereas if you go on the east side, you have a school, the maintenance building, the office, the rec centre, the high school and the public school. There’s the health centre too, which used to have a store and a cleaners.”

The expressway would have passed through the Annex, a Toronto neighbourhood of considerable political and cultural clout, filled with just the kind of university professors, lawyers, and media-savvy sorts who could mount a campaign to stop a freeway.

The two highway crossings came to be known as “Overbridge,” where Flemington Road crosses over the highway, and “Underbridge,” where Ranee Avenue crosses underneath it. “You have to walk all around to get anywhere,” says Bishop-Earle. “You just can’t go through the middle of the community.” As we walked the ring roads, Flemington and Varna Drive, the distances became apparent. Although the other side of the community is seemingly a stone’s throw away, it takes considerable time to get from one side to another as there are no direct routes, a small thing at first glance but enough of a trek that mobility and social patterns change. Darmanin recounts a childhood episode walking back home via the underpass when a stranger in a car followed him, giving it a sinister air from the “stranger danger” era, though today the walls of the underpass are brightly coloured with murals that read “HOME” and “LIMITLESS.”

Like Bishop-Earle, Darmanin believes the ideal solution for the Allen problem is to cover it up. “Making it one community, connected through a green overpass, that would be the biggest and best solution for that neighborhood,” he says, pointing out that the two new “gateway” residential buildings at the north side of the community are by the same developers and have a visual cohesion that brings the two sides together. “It’s the start of recognizing that it’s one community.”

“One of the things that we were kind of surprised about, but it was an important thing to learn, was that the community felt very strongly that they wanted the revitalization to be done altogether,” says Carmen Smith, former manager of community renewal and revitalization at Toronto Community Housing (TCH). “Part of this was because the Allen divided the community.” Smith started working there in 2008, early on in the Lawrence Heights revitalization process. TCH had 17 community animators who facilitated the consultation process, undertaking community surveys to find out what residents hoped and feared as change was coming, and what positive things they thought could be brought in.

“Like with any progressive and positive plan, you need the funds and financial resources to bring the vision to bear, along with the political will,” says Smith of the Allen question. They looked at a variety of options, including a park that straddled it or simply making the highway more of an attractive urban road, with cycling paths, a park, and green spaces alongside it that both sides of the community could share. They even talked about filling it in, but considering that Toronto is spending over a billion dollars to rebuild the Gardiner, it’s unlikely there is any political will to remove a highway right now. Still, much can be done. “Certainly from the community there was a lot of interest in what revitalization could do with the Allen. Residents were showing up, deputing and speaking out, saying, ‘We want our community to be united.’”

Covering up a transportation corridor that passes through where lots of people live is not unprecedented. Since the Allen was paved in a Detroit-style freeway trench (below grade to allow surface streets to pass over without long overpass approaches) it’s easy to imagine it being completely covered. In downtown Chicago, Millennium and Maggie Daley Parks were built over a massive railway yard, creating a much-celebrated public space with the Pritzker concert pavilion and Cloud Gate, the bean-shaped reflective sculpture by Anish Kapoor. Similarly, in Melbourne, Federation Square and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image were created by covering that city’s main rail corridor.

At the tip of Manhattan, Battery Park is built over both the Battery Tunnel and FDR Drive. In Seattle, the appropriately named Freeway Park was created over Interstate 5, and other American cities like Pittsburgh, Dallas, St. Paul, and Atlanta are considering “deck parks” to cover freeway gashes in their urban fabric. In downtown Toronto, slow progress is being made on Rail Deck Park, a fanciful plan to cover the railway corridor west of the CN Tower and create a park among the tens of thousands of new residential units that have been built there. Most recently, Mayor Tory signalled his support for a city push to expropriate the air right above the railway, though the park’s massive price tag is so far unfunded.

While some of these locations, like the proposed Rail Deck Park, are in shiny downtown neighbourhoods, some of the proposed land bridges seek to correct historic planning wrongs that saw highways built through lower income neighbourhoods where people of colour lived. Lawrence Heights is an interesting case because, though the neighbourhood came first, it was built with the expectation that the highway would pass through the middle of it and was designed to accommodate it, at least spatially.

For residents like Denise Bishop-Earle, what’s certain is that current plans aren’t enough to connect the community. “They’re building a big park on both sides of the Allen and the only thing that’s going to connect them is a footbridge,” says Bishop-Earle. “It all comes down to who’s going to fund it, where’s the money coming from, and the will of the government.” As the subsequent phases of the revitalization are planned, there’s an opportunity to do something better for the community and city, something akin to a Rail Deck Park, but covering the expressway. If there’s will downtown, why can’t there be will up here?