On a drizzly Friday afternoon in January, the players filed into the John Polanyi Collegiate Institute gym—each teenager taller than the last, all gangly limbs and oversized sneakers. Fluorescent lights in protective cages illuminated the modest surroundings. A school staff member struggled to set up the scorer’s table while three men squeezed into the equipment room next to the volleyball nets, peeling off their down jackets to reveal tight-fitting referee’s uniforms.

It was basketball night in Lawrence Heights and the kids from the Toronto Basketball Academy (TBA) were here to defend their home court against the visiting team from London Basketball Academy. Fans and parents from London sat on one side of the fold-down bleachers, screaming at the referees after every perceived missed call; kids from John Polanyi lounged on the other side, wearing hoodies and headscarves, watching the game with typical teenage aloofness.

Yusuf Ali ran his team through their warm-ups. The first-year head coach was perhaps the smallest person on the floor—a former point guard who earned the nickname Rhino for his habit of putting his head down and driving into his defender. A few years ago, Yusuf was the MVP of a college team that won the national championship. Now the 26-year-old was back where he grew up, hoping to bring his kids a win tonight and then, hopefully, bring them much, much further.

In the last decade, the idea of a kid journeying from the John Polanyi gymnasium to the NBA has suddenly become within the realm of possibility. The number of Canadian preparatory schools devoted to turning teenage hoopers into collegiate and even NBA stars has exploded. An entire infrastructure of scouts and local boosters has sprung up, making mixtapes for YouTube and covering high-school games on Twitter, all for the eyes of influential scouts. Top American college coaches now make their way to Ontario gyms, hopping on planes and braving the Canadian winter to take a look at a sixteen-year-old who might be the next Jamal Murray.

The Toronto Basketball Academy is one of the oldest of these programs, but it’s also an outlier. Most of the prep teams TBA plays against are based out of private schools—shiny institutions in the suburbs with top-of-the-line training equipment, big sponsors, and gleaming new facilities. Playing out of a public school in a community that struggles with poverty and gun violence, TBA has none of those advantages. The kids don’t get free Nike sneakers. The team has to haggle with the school for gym time. Coaches are unpaid, juggling jobs at Shopper’s Drug Mart or as engineers.

What TBA does have, the team insists, is a rock-solid culture and an underdog mentality that has served them well. The program has sent more than sixty kids to play college basketball on scholarships, the best playing in the NCAA’s Division One. When Yusuf Ali looks around, he doesn’t see a scrubby gym in a poor inner suburb. He rhymes off a list of players—“Amir Gholizadeh at Chicago State, Marcus Masters at UNB, Patrick Emilien at Western Michigan”—local heroes who have graced the John Polanyi hardwood. “The guys that play at this school are legendary,” he says fiercely. “Our players are playing in a historic gym. Playing here is what gives us our advantage.”

“The team was never meant to be churning out high-level scholarship athletes. This was not intentional. Our original intention was to just to keep kids out of trouble.”

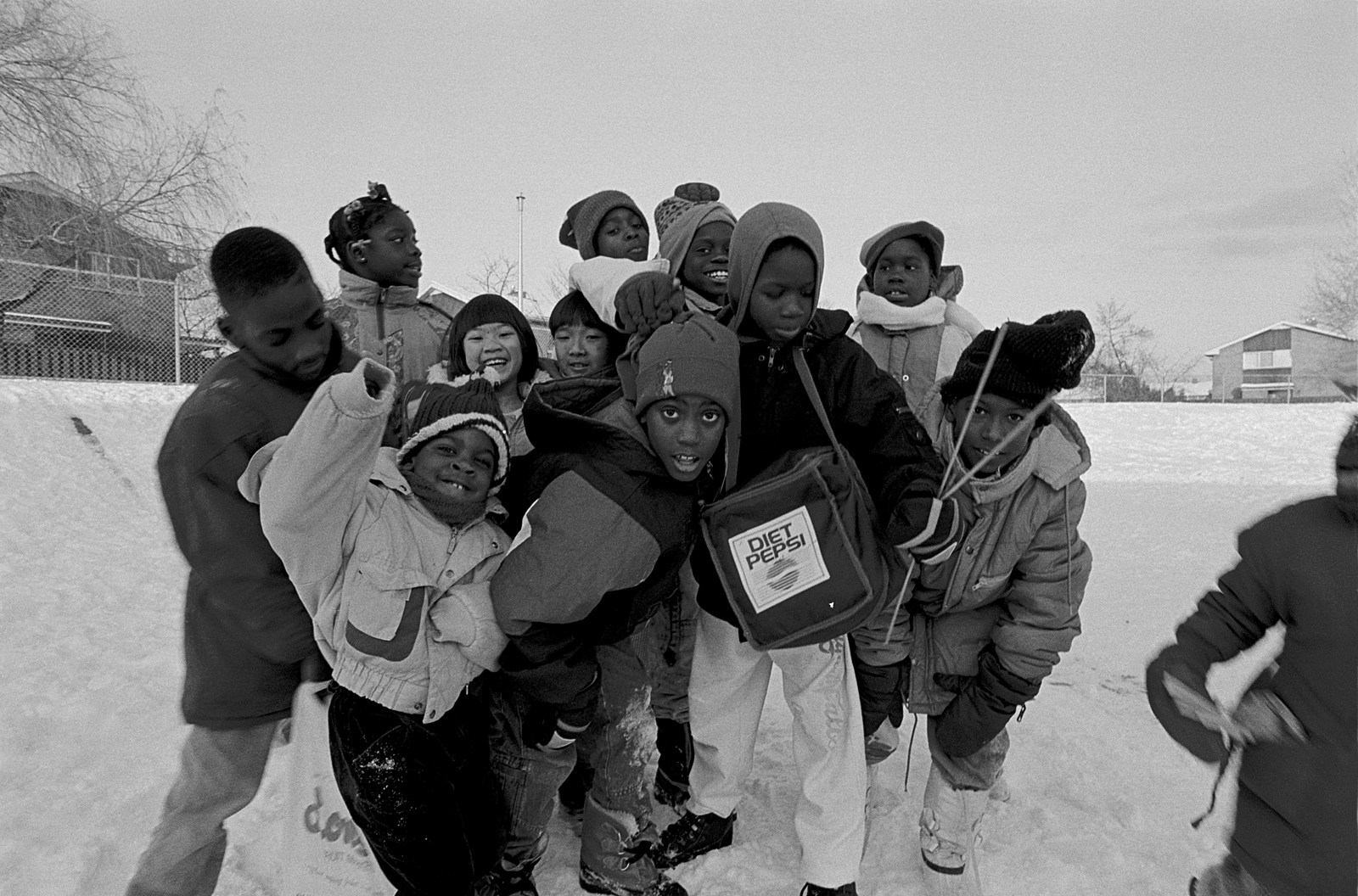

When Tahbit Chowdhury and Adeel Sahibzada founded the program that would become TBA, back in 2012, it was just a bunch of kids playing in parking lots. “The team was never meant to be the conveyer belt it has become,” says Chowdhury. “It was never meant to be churning out high-level scholarship athletes. This was not intentional. Our original intention was to just to keep kids out of trouble.”

When it came time to find a permanent home, they considered a couple of different places before deciding to partner with John Polanyi CI. For TBA, the fact that Lawrence Heights is a tough neighbourhood was a draw, not a deterrent. The team’s goal, after all, was to help the kids that needed it, to use basketball as a conduit to education and self-improvement. “The people here, they’re not going to be part of the Toronto transformation,” says Chowdhury. “When we talk about Sidewalk Labs and all of these things that are coming around—they’re not going to be part of that.”

While there were plenty of high-minded reasons for the team to come to a community like Lawrence Heights, assistant coach Jovon Biggart acknowledges another, simpler motivation: “It was the neighbourhood where Ahmed Ali was from.”

Ahmed, Yusuf Ali’s younger brother, was a member of that nascent prep team and a growing local legend—a skinny point guard with an aggressive style and the kind of smooth shooting stroke you could build a basketball program around. Kids from the neighbourhood still talk about the time he put up 103 points in the John Polanyi gym, draining an absurd 23 three-pointers from all over the court. It was only the second time ever a Canadian high-schooler had scored a hundred points in a game, following future NBA player Denham Brown. The feat made news across the continent. It inspired Drake to wear an Ali jersey on stage at a concert in Tampa, the number 103 emblazoned on the front.

The next year, the point guard got a full-ride scholarship to Eastern Florida State College, before transferring to Washington State in 2018. In 2019 he was set to play at the University of Hawaii, but health issues have kept him sidelined.

Ahmed’s success was proof that a kid from the neighbourhood could make it and that the humble John Polanyi gymnasium could be the launching pad for much bigger things. “I think he’s the best hooper to come out of the city,” says Yusuf today. “He’s my younger brother, but he inspired me to become a better basketball player.”

In many ways, the Ali family is the heart of TBA. Yusuf and Ali are two of ten siblings raised in the neighbourhood, the children of Somali immigrants. Dalmar Ali, a cousin, is an assistant coach. Another brother, Said, played basketball too, though not with the same intensity as his brothers. “He was a joker, people called him Foolish,” says Dalmar.

Late on Sunday, July 30, 2017, Said was shot while getting drinks and snacks with some friends. An onlooker found him lying in a parking lot at Lawrence near Dufferin. Paramedics rushed him to Sunnybrook, where he died of his injuries. The murder is unsolved to this day.

The family was devastated. The neighbourhood was devastated. “Foolish, he was like the smile of our community,” remembers Dalmar.

That year, Yusuf was playing at Seneca College. He considered quitting basketball, leaving school. He sat down with his coach, Jay McNeely, who urged him to stay at Seneca and keep going. “He was the reason I kept level-headed and sane,” says Yusuf. “He reminded me every day, there will be better days.”

Yusuf dedicated that season—every bucket, every assist—to the memory of Said. Seneca was a small program that had never won much of anything, but that year Yusuf led them on a miraculous run. They won the provincial championship. Then they won the national title, with Yusuf named MVP. “I just remember him yelling that this was for his brother,” remembers Dalmar.

The next year, Yusuf was recruited to play with the Ryerson Rams. At the end of the season, the TBA founders came to him with an offer: come back to Lawrence Heights and become the team’s head coach. Yusuf was torn. He had opportunities to continue playing ball, to join a team in the Middle East or China, to continue chasing the dream. But his coach at Ryerson that year, Roy Rana, told him something that stuck with him. “Use the game, don’t let it use you. Play in the real game.” He decided to come home.

“Once his brother passed away, he started looking at life a little bit differently,” is how Dalmar explains it. “Like he’s trying to leave a legacy behind and trying to build something big. And I think honestly that’s one of the biggest reasons why he took this position here—to be able to leave something behind, to be able to say, ‘I did this for my brother. I helped these kids.’”

“Once his brother passed away, he started looking at life a little bit differently. Like he’s trying to leave a legacy behind and trying to build something big.”

In the gym that January night, the team was in rough shape. They’d been battling injuries all month. Then the flu spread through the locker room, taking down half the team.

Despite all this, by the fourth quarter the game was still tight, the teams taking turns trading the lead. “I honestly can’t believe we’re holding in there,” muttered Fazlur Malik, the team’s digital media manager.

“Wall up, wall up!” Yusuf yelled helplessly, watching as the London team came down the floor and scored in the paint. In a black turtleneck, slacks, and loafers without socks, the coach looked like a beatnik having a bad night. He was a vibrating wire of energy—prowling the sidelines, yelling directions in a near-constant staccato, slamming his open palm onto his fist in anger at a missed defensive assignment. As a point guard, he was used to having the ball in his hands, of being able to control the game. Now he was stuck on the sidelines, helpless.

With 1:24 left, TBA was up by just one point, 69-68. Yusuf called a time out. In the huddle, he was calm and collected. He drew up a play. “Our last possession of the game is our best possession of the game,” he said firmly. He looked at his players. “Do you want this? Family on three.”

The players put their hands in. “One, two, three, family!”

Jasha’jaun Downey dribbled the ball down the court. He had the flu. He’d missed practice that morning and hadn’t started the game. The teenager had come to Lawrence Heights all the way from Halifax, where he’d been one of the top-rated point guards in the country. He seemed to represent a new era for TBA—evidence that the team wasn’t just helping local kids get out of a bad neighbourhood, but bringing kids from across Canada to this gym, trying to build something lasting in Lawrence Heights.

As the clock ran down, the kids in the stands who’d previously been looking at their phones were suddenly paying full attention, a current of electricity moving through the crowd. Downey drove hard toward the basket, right into the chest of a helpless London defender. He double clutched as the whistle blew—a foul against London—and sent the ball into the air.

In the moment it took the ball to rattle around the rim and settle through the mesh the cheers in the auditorium grew into a roar. Bucket and one—game over.

Downey pumped his fist. He pounded his chest, a fierce look on his face, as the rest of the team rushed to high-five him.

Yusuf smiled on the sidelines. In the grand scheme of things, in the real game, it wasn’t much. It was just one shot—one game in a scrubby gym in a corner of the city most people don’t want to visit—but it was another step forward. Who knew where it might lead?