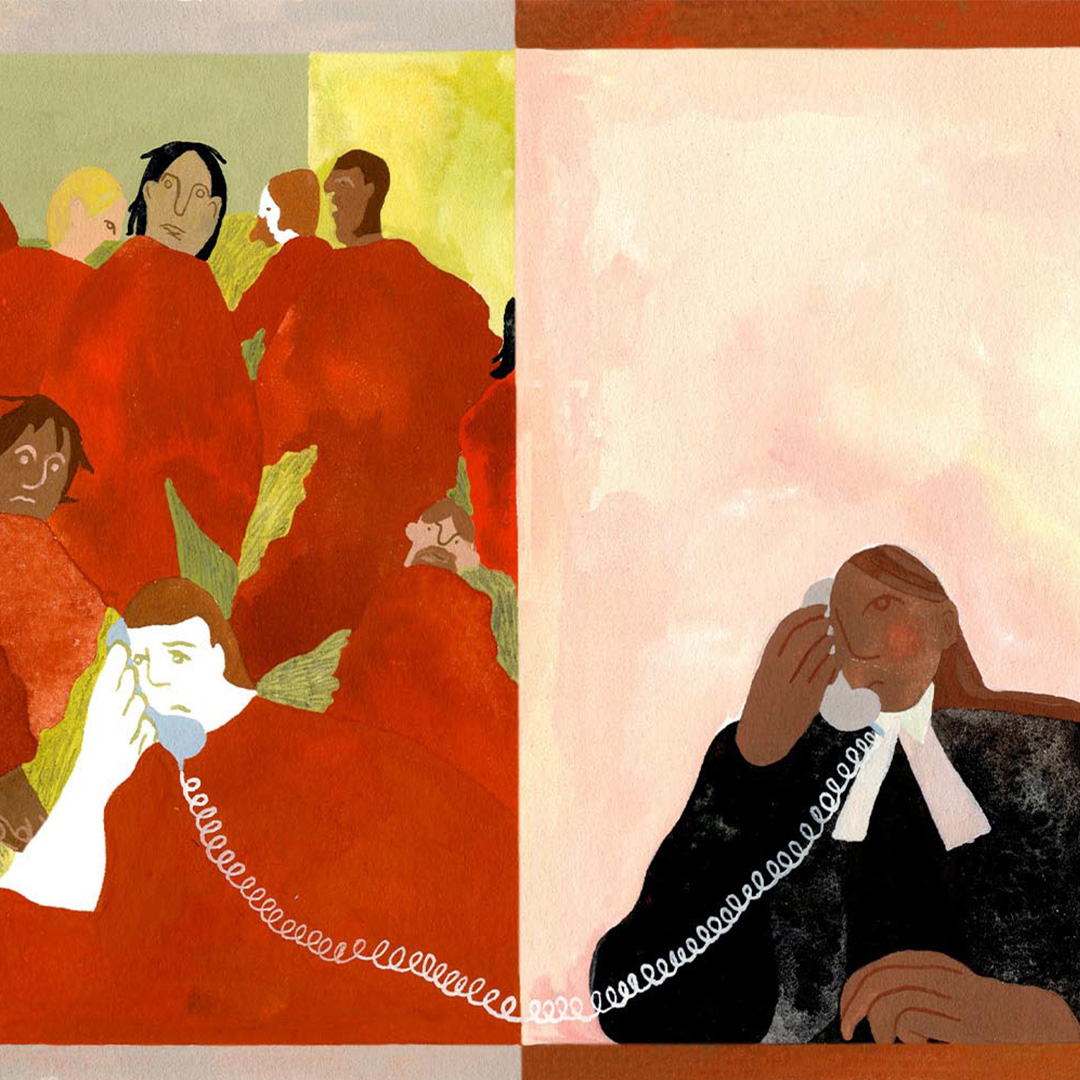

It’s Thursday morning in Toronto, and bail court is in session. Instead of the usual location—a stately downtown building, say, or a dreary suburban low-rise—the proceedings now happen over the phone. The only people at the courthouse are a court reporter and a clerk who manages the teleconferencing system. Everybody else—the lawyer, the crown prosecutor, the accused, and the justice of the peace (JP) who makes the decisions—has called in to a dedicated line.

It’s a strange setup. People accidentally speak at the same time, or provide lengthy answers to questions only to realize they’ve put themselves on mute. The proceedings are interrupted by dogs barking or babies crying. In the last four weeks, new “courtroom” rituals have emerged. Whenever anybody speaks, they must first re-state their name (when you can’t see faces, it’s hard to know who’s talking), and JPs are now in the habit of giving frequent, exasperated lectures on phone etiquette. “Someone’s interfering with their microphone,” the JP says at one point, in a tone that conveys annoyance. “Can I have a word with the accused?” a lawyers asks during a later hearing. “Please do,” says the JP. “But keep in mind that everyone can hear you.”

Court proceedings are meant to happen in-person, and many courthouses aren’t even equipped for multi-party videoconferencing (hence the reliance on phones). Today, criminal trials are no longer moving forward at all, but bail court is still on, since people have a right to a hearing within 24 hours of being arrested.

The very notion of rights is especially fraught in the time of COVID-19, in which a stint in jail can result in infection, or potentially death. Two prisons in Quebec and one in Ontario have already seen serious outbreaks. At the medium-security wing of the Mission Institution in British Columbia, more than fifty inmates have tested positive for the virus and one has died. Such figures aren’t as dire as those in Chicago’s Cook County Jail or New York’s Rikers Island, but outbreaks have a way of growing. This grim reality raises an obvious question: Why are so many people still incarcerated at all? If a courtroom is a dangerous breeding ground for infection and must therefore be closed, surely a jail is exponentially worse. Why shutter one and keep the other packed?

In virtual courts across the country, this conundrum is on people’s minds. Lawyers are raising the issue of prison infections repeatedly, while many (but not all) prosecutors, JPs, and judges are offering concessions they might normally deny. On Thursday morning, the first bail hearing involves a man accused of assault. He has no one to act as surety: that is, he doesn’t have a person who can promise to keep an eye on him if he’s set free. In theory, this should be a deal-breaker, the JP explains, but today, “given the extraordinary circumstances in which we find ourselves,” the man is released on a $500 bail.

When prisoners get severely sick, they wind up in hospital, and when wardens need groceries, they shop at the same places you do.

As the day wears on, many other people “appear” before the court: men accused of uttering threats while brandishing weapons, committing minor acts of theft, or violating previous bail agreements. In most cases, they are granted temporary freedom, often on lenient terms. Toward the end of the day, a man facing unspecified charges phones in from the Toronto South Detention Centre, a notoriously violent prison, which has already seen a handful of infections. The sound quality is terrible, as if the call were coming from the International Space Station. Eventually, a warden steps in to explain: “As a COVID-19 precaution, we’ve had to double bag the phone.” The man’s bail hearing is adjourned for a later date.

When it opened six years ago, the Toronto South was touted as a state-of-the-art facility; the fact that it is now resorting to such jury-rigged precautions as bagged phones reveals a great deal about how poorly the carceral system is handling the pandemic. In other institutions, reports abound of inmates being denied hand sanitizer because of its alcohol content and wardens receiving improper instructions on when and how to use personal protective equipment.

Other risks, however, are a function of the brute reality of prison life—the dirtiness, the double bunks, the long lines for food, the abundance of plastic and metal surfaces on which a virus can survive, and the fact that guards maintain close physical contact with prisoners while escorting them throughout the facilities. In a recent affidavit, Toronto epidemiologist Aaron Orkin testified that prisons simply aren’t designed for social distancing. “It is extremely likely that COVID-19 will arrive in nearly every correctional facility in Canada,” he predicted, “and therefore extremely likely that almost all inmates in these settings will be exposed in one way or another.” It’s tempting to imagine that these institutions, unhealthy as they may be, are at least sealed off from the rest of society, but this isn’t true. When prisoners get severely sick, they wind up in hospital, and when wardens need groceries, they shop at the same places you do.

To fix this problem, solicitors general and attorneys general across the country need to put out emergency directives, authorizing releases (followed by self-quarantine) on a massive scale, thereby whittling down the prison population to only those inmates who present serious threats to public safety. The justice system has made moves toward this goal via generous applications of existing programs, like parole and temporary passes. The Ontario Government has also made a bulk purchase of ankle bracelets to facilitate remote monitoring.

As a result of such measures, many prisons are perhaps better described as crowded, whereas before they were over-crowded. But in a pandemic, such distinctions hardly matter: there are still hundreds of people held at places like Collins Bay, Beaver Creek, Stony Mountain, and Warkworth, and tens of thousands in custody across the country. And so, lawyers will continue to phone in to empty courtrooms—at a time in which restaurants, parks, and offices are likewise empty—in order to prevent people from going to jails that remain, by any reasonable definition, full.

There’s a painful irony in all of this, and also in the fact that, in the twenty-first century, we’re still relying on archaic carceral institutions—sunless, overcrowded warehouses that aren’t conducive to human health. Even in normal times, outbreaks of HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C are common enough in Canadian jails. But a pandemic can be clarifying. Perhaps it will prompt us to look directly at uncomfortable truths, forcing a reflection on the way our prisons are designed—and on whether everybody inside really needs to be there.

The third hearing at virtual bail court involves a homeless man accused of assault. When the JP asks a question of the prisoner’s legal representative, the man mistakenly answers. “These are not questions for you,” the JP exclaims, sounding both kind and exhausted. “I’m sorry. I’m not used to doing this by phone,” the man responds. “That’s okay, sir,” the JP says, after a pause. “It’s awkward for all of us.”