A few weeks ago, on a rainy Friday morning, I visited Clay and Paper Theatre’s workshop in the Sterling Studio Lofts, an old munitions factory near Bloor and Lansdowne that’s one of the last live-work spaces for artists in Toronto. The high-ceiled room was filled with the larger-than-life puppets the company uses in their work—papier mâché pigeons sitting next to a vibrantly painted grizzly bear head, an impossibly delicate beluga hanging across from a 15-foot “God” puppet, which gazed down with the totemic solemnity of an Easter Island statue.

If you’ve happened on their “Night of Dread” processions in Christie Pits or have wandered through Dufferin Grove in the summer, you may have seen Clay and Paper’s work. Witty, political, and often surprisingly moving, they use giant puppets and music to create theatre in the community, with the underlying philosophy that art in an auditorium is often wonderful, but art encountered in the world, with the grass under your feet and the sun on your face, can be transformative.

This is the company’s 30th year. This week, founder David Anderson is a finalist for the Celebration of Cultural Life Award at the Toronto Arts Foundation Awards. Then, at the end of the month, he’ll pack up the studio for good.

“We’ve lost or been kicked out of five spaces in 12 years due to developers or obscene and unsustainable commercial rents,” says Tamara Romanchuk, Anderson’s creative and life partner. They’ve had spots at the Galleria Shopping Centre and in a garage, and tried to secure space with the TDSB. Now, with the Sterling lofts slated for redevelopment and business tough, it seemed they’d run out of options. The audiences were still coming, but it was time, once again, to pack up and regroup.

Amid a cascading series of bad news stories about the city’s major arts institutions—with Artscape in receivership, Hot Docs broke and in disarray, local theatre companies in crisis, the Fringe Festival struggling, the Just for Laughs Toronto festival closing, and TIFF and Contact looking for title sponsors—the fate of tiny arts organizations like Clay and Paper doesn’t get much attention.

But the wrenching economic calculations faced by the company are the same ones faced by so many in the city. Toronto’s artists are up against stagnating funding, COVID-era changes in audience behaviour, and a housing crisis so severe it threatens to subsume every other civic issue; how do you argue for the preservation of artist studios or musician practice spaces when people need homes? The questions they’re left with feel existential. How do you create art in Toronto in 2024? And, if the answer is “you don’t,” then where does that leave the city?

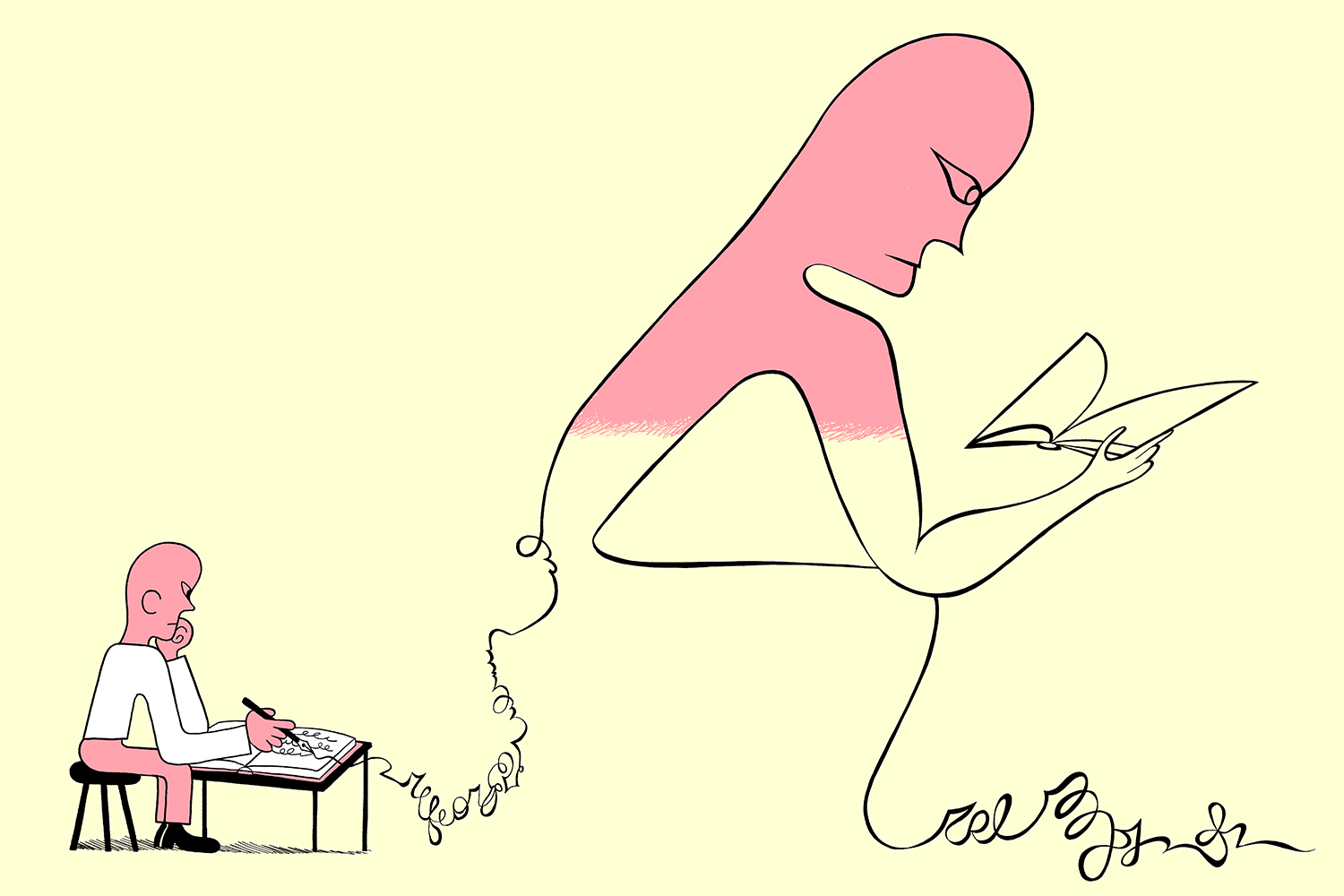

The Local’s “Art + Money” issue addresses those questions directly, with stories about the people making art in this city despite the dire economic realities—from indie filmmakers creating a brand new cinematic identity for Toronto, to international students turning the struggle of their lives in Canada into pop stardom back in India, to a collective of young, BIPOC visual artists looking to build a world outside this city’s traditional institutions.

Art + Money

Subscribe to our free newsletter to get our stories delivered directly to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

While artists are generally thought of, either romantically or derisively, as starving bohemians whose passions transcend economic concerns, Tamara Jones focuses on the “worker” part of an arts worker’s identity. “To be an arts worker has become an exercise in navigating precarity, constantly defending the validity and value of our work,” they write. “Nearly 70 percent of Toronto’s arts workers make less than $43,000 annually, and most rely on short-term gigs with few labour protections and no health benefits.”

For Jones, and others, there’s a strong economic argument that money invested in the arts is well spent. Prior to the pandemic, each dollar invested by Celebrate Ontario, the funding body for events and festivals, generated $21 in visitor spending on things like restaurants and taxis and overpriced ice creams. Funding small arts organizations, the argument goes, is a canny way to incubate the projects and artists that will later grow into tax-revenue-generating hit-makers.

That’s true for Clay and Paper Theatre. Over the decades, Anderson explained, his company has trained hundreds of young artists, many of whom have gone on to lead successful institutions of their own. That has real economic value. “But that’s not the point of it,” he said, his voice rising in passion. “That isn’t the point of it at all. The point of it is to do some thinking together, to look at where we’re at, to look out at the world.”

The value of this is hard to express and impossible to quantify. But it’s no small thing. People don’t choose to live in a city because they want to be close to a giant puppet show, of course. But it’s the accumulation of these small cultural experiences—the puppets in the park, the concerts in the church, the second-hand buzz of walking past a festival tent spilling out onto the street on a Saturday night—that make a city desirable, giving it the life and vibrancy that help justify paying so much to live here. The art produced here is what helps us see the city as more than an agglomeration of Rexalls and anonymously instagrammable coffee shops plunked into an uninspiring topography. That’s the point of it.

Correction — April 23, 2024: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Clay and Paper Theatre once had studio space with the TDSB.

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Foundation. All stories were produced independently by The Local.