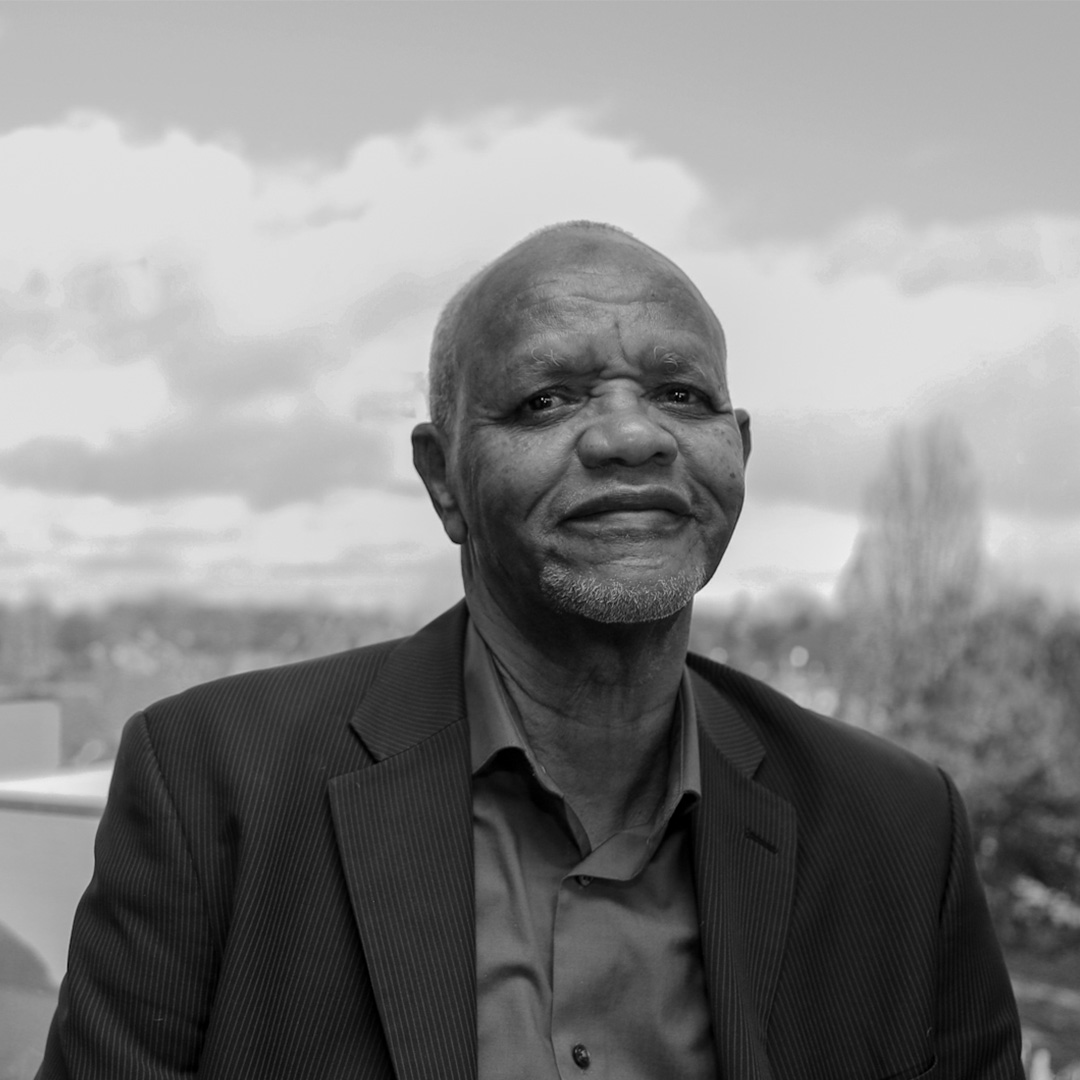

In 2006, when Mohamed Ali-Aden’s daughter told him she was the only one in her Grade 3 class who didn’t know how to multiply, he was taken aback. “You’re the only one?” he asked. She replied matter-of-factly. “Yes. Everybody knows multiplication.”

A Somali raised in Kenya, Ali-Aden had served as an elementary teacher before coming to Canada. He knew the value of education, how important it was to open up opportunities. He and his family had moved to Lawrence Heights in 2004. “The local school was one of the worst in Toronto,” he remembers. In 2006, the Fraser Institute ranked Sir Sandford Fleming Academy 658 out of 664 schools in all of Ontario. “Things were so bad that kids would actually tease other children for saying they wanted to go to college or university,” he says.

Drawing on his training and experience teaching in Africa, he decided to start tutoring his daughter. Quickly, however, he realized that she wasn’t the only one in the community that needed help. He remembers stumbling upon a Toronto Star article that said that the emphasis on reading and writing in Canada’s curriculum begins to wane steadily from Grade 4 onward. As a result, “children who aren’t reading well by the end of Grade 3 are at risk of dropping out or failing to graduate.” For Ali-Aden, the article carried a warning for his community.

“If it can be surmised by Grade 3 whether a child will be successful, that means there’s something wrong with the lower levels of the education system,” Ali-Aden thought. “The problem is that the ‘one child’ is actually a number of children—and they are all from the same community.”

Ali-Aden began tutoring neighbourhood children, all free of charge. As he deepened his involvement in the community, joining various parent networks and education committees, he eventually met Owen Christopher Hinds from Pathways to Education Canada—an organization that was doing the kind of neighbourhood education Ali-Aden saw as so vital, but at a much larger scale.

Pathways to Education grew out of a somewhat counterintuitive idea: that the best way to improve the health of a community might not be in the hospital or doctor’s office, but in a classroom.

In 1999, Carolyn Acker, the executive director of the Regent Park Community Health Centre, began working to address neighbourhood poverty. Her efforts were based on her observations and experience as a trained community health nurse, as well as conversations with local parents and community members, who told her they were concerned about the future of the neighbourhood’s youth. The high-school graduation rate in Regent Park was among the lowest in the city and kids had few opportunities.

At the time, few health care professionals saw a connection between educational attainment and community health. Yet, as many studies have since shown, education is an important social determinant of health. One report noted that post-secondary education not only increases employment opportunities but “can also increase the capacity for better decision making regarding one’s health, and provide scope for increasing social and personal resources that are vital for physical and mental health.”

Acker was particularly interested in the concept of “community succession,” the idea that youth within a community would eventually replace the existing health care providers, becoming the nurses, physicians, and support workers for the community in which they were raised. This would not only create employment for community members but also improve care, ensuring that health practitioners had a deep knowledge of the community they were serving.

Acker and her colleagues put their vision into practice, launching a program that offered tutoring, mentoring, financial support, social skills training, and a variety of other services in Regent Park. Five years later, the high-school drop-out rates had decreased by more than 70 percent and post-secondary attendance had increased by more than three hundred percent. The program was so successful that, in 2005, Acker founded Pathways to Education Canada, an organization that would bring the Pathways Model to low-income communities across the country. In 2007, Pathways came to Lawrence Heights.

Pathways to Education grew out of a somewhat counterintuitive idea: that the best way to improve the health of a community might not be in the hospital or doctor’s office, but in a classroom.

When Mohamed Ali-Aden met Owen Hinds, the director of Pathways to Education in Lawrence Heights, he was impressed by his commitment. “His plan was to sit at every table in the community and have dinner with them,” remembers Ali-Aden. “Now that’s not possible but that shows the extent to which he wanted Pathways to succeed.” He began volunteering with Pathways in 2007, where he served as a tutor before eventually working as a Program Facilitator.

Today, the Pathways at Lawrence Heights program has 270 registered students and fifty volunteers. Given the costs of office space in the area, the program operates out of multiple sites in the community, including the local mall, the Lawrence Allen Centre. While there are other, less central spaces that could be cheaper, Pathways needs to be accessible, and the mall is close to the subway station and a number of neighbourhood schools.

On an afternoon in January, the small office tucked away on the fourth floor of the shopping centre is filled with program staff and volunteers working tirelessly. Ontario college and university applications are due and the staff’s offices and computers double as work stations for students to submit applications and print documents. Staff jog through the hallways, delivering print outs, giving advice, and answering questions. In one office, a hotel call bell sits atop a filing cabinet. In a few months, it will be sounded whenever a student is accepted to a post-secondary institution.

A five-minute walk away from the mall, in a large room on the top floor of the Unison Health and Community Services building, large tables are spread across the room with placards indicating subject areas—math, science, English. Students are given a snack before sitting around the table with a volunteer who works with them on their homework. Two one-hour after-school tutoring sessions are scheduled each day, Monday through Thursday. Until recently, the sessions were an hour and fifteen minutes, but concern for youth safety after several shooting incidents led staff to shorten them.

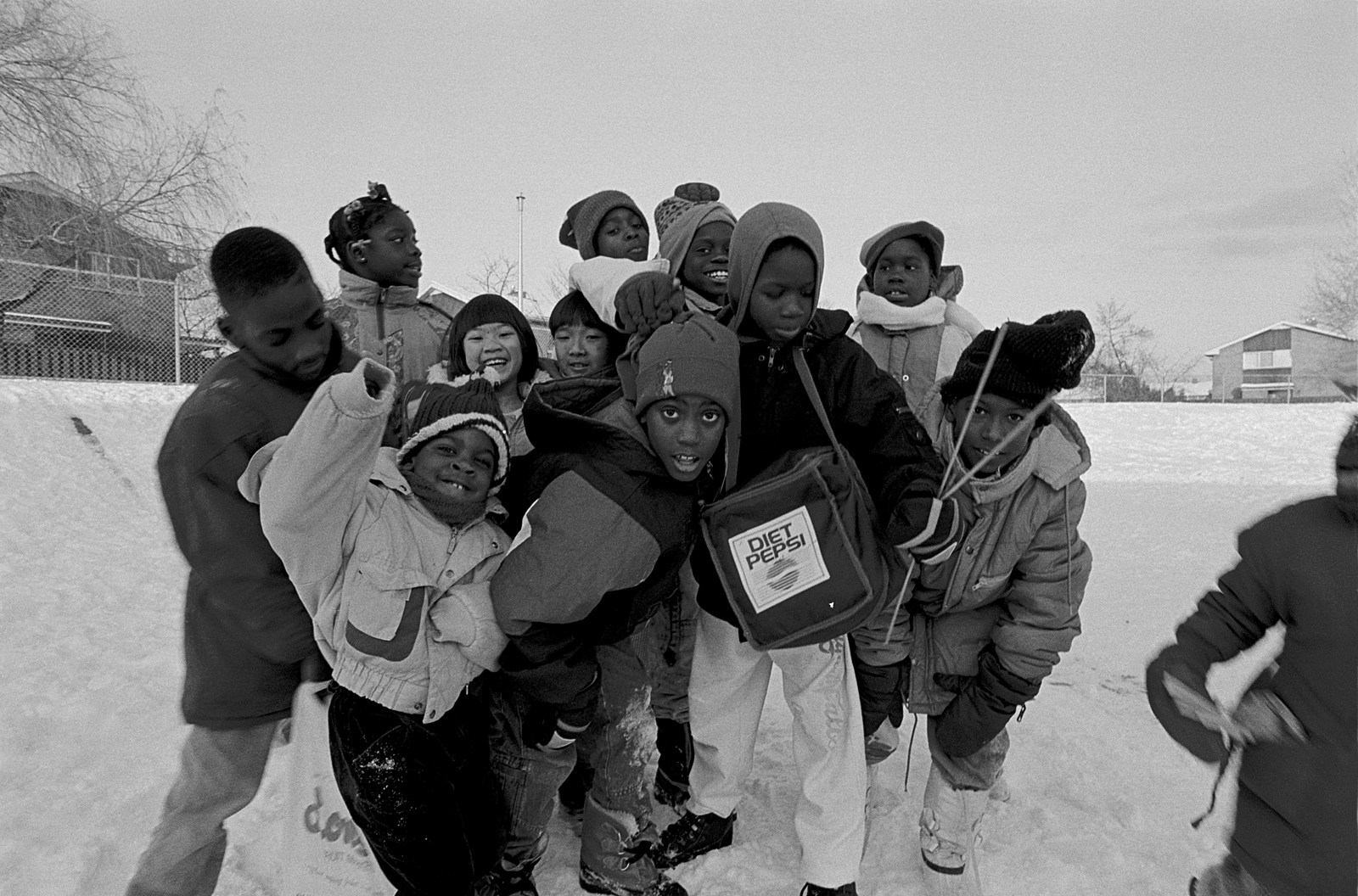

The students reflect the demographics of the community: most are racialized, coming from East Africa, Latin America, and South Asia. Many live in the more than 1,200 rent-geared-to-income housing units spread out across the hundred acres that constitute Lawrence Heights. The volunteers come from similarly diverse backgrounds: many are community members and even former Pathways students, some are retirees, others are professors, teachers, engineers, and other working professionals looking to give back.

Ashna Parbatie, a 22-year-old woman from the neighbourhood, remembers the Pathways program fondly. She attended throughout her four years of high school, brought to the program by parents who thought that it might help her avoid some of the challenges her older brother faced.

Parbatie describes her personality in high school as “dormant,” saying that she didn’t think she could get a job because she was “just too anti-social.” She credits the Pathways staff for helping her to come out of her shell and become more involved in the community. Now a third-year human geography major at the University of Toronto, Parbatie still visits the Pathways office about once a week to chat with the staff, print a document, or get advice. “It was just nice to know that there was someone who cared about you and saw potential in you and just gave you their time,” she says.

Hinds echoes the importance of not only equipping youth with academic skills, but also social skills. “If you’re not able to go into social environments and social situations… then you’re on some level still at a disadvantage,” he says.

In all aspects of the program, the goal is always to remove barriers to success and to do so without judgment. Sometimes this means simply printing off documents for a student or supplying them with internet access to do research. Sometimes it means encouraging a student who smokes marijuana every evening to lay off on weeknights. It also means training and supporting parents, some of whom do not feel empowered to speak with high school staff about their children’s needs. In many cases, a language barrier adds anxiety to already difficult and daunting interactions, furthering a sense of alienation and disengagement.

After more than a decade, it is clear that Pathways has had a profound impact on Lawrence Heights and is much beloved by the community. “If we can get these young people engaged and better educational outcomes, then we think that we can actually start this process of transforming not only their individual lives but also their entire community,” says Hinds.

“In one office, a hotel call bell sits atop a filing cabinet. In a few months, it will be sounded whenever a student is accepted to a post-secondary institution.”

Today, Lawrence Heights is a neighbourhood in transition. Since the early 2000s, the community had been targeted by the city for revitalization as one of the city’s “priority neighbourhoods.” A 2004 report by the United Way entitled Poverty by Postal Code found that poverty had become “spatially concentrated” in the inner suburbs of Toronto, particularly in the former City of North York. One of the chief concerns raised by participants in the study was that the stigma of poverty and crime would lead to a wholesale neglect of the community—that their neighbourhoods would be written off by outsiders. Like Ali-Aden, they feared that the barriers to opportunity would grow so high they’d become insurmountable. This isn’t so hard to imagine in a community that not-so-long-ago was enclosed by a fence with only four pathways out.

Today, with the revitalization project underway, the future remains unclear for many residents. The new local high school, John Polanyi, is among the best rated in the city, attracting students from outside of the community. Many parts of the fence that once isolated Lawrence Heights from the rest of this city have been removed, though some remain.

Mohamed Ali-Aden continues to move through the neighbourhood, bumping into familiar faces in his work as a freelance Somali interpreter and occasional Uber driver. As an interpreter, he too often sees former students and their parents in the courtrooms trying to navigate their way through the justice system; sometimes, despite all of their efforts, the barriers are simply too difficult to overcome.

There are, however, far more success stories than not, far more instances of students who have found support in Pathways and gone on to be successful. The key to the program, Ali-Aden believes, is the relationships. “Pathways went deep down,” he says. “The only thing they didn’t do was go into the kitchen or the living room, but that’s it. They’re calling the parents, they were giving bus fare…these kids were taken care of.”

Recently, Ali-Aden picked up a former student while driving Uber. The student had been someone whose attitude and academic performance had always made Ali-Aden worried. But here he was, years later, getting a ride to his job as a supervisor at a construction site because his car was in the shop for repairs. Ali-Aden was thrilled to see the former student; it is always a joy to pick up former students and to hear about their progress. Their successes, both large and small, reveal the power of education—to open new pathways, even in a place where only four roads lead in or out.