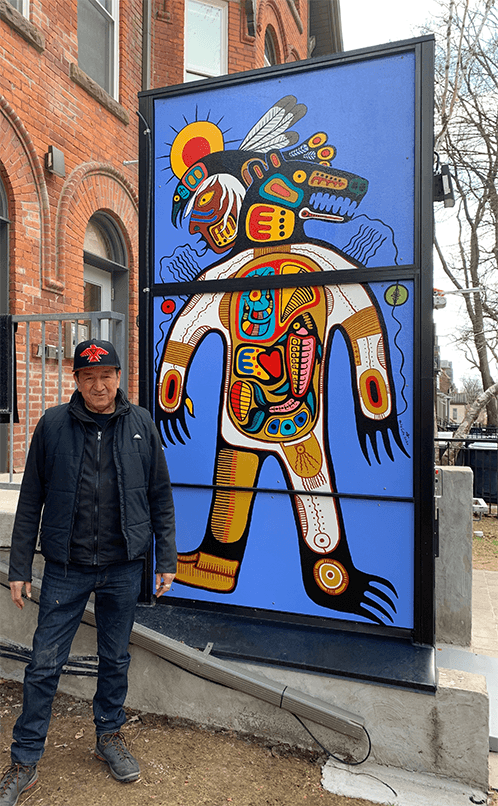

It’s way more than just public art. That is the main message I took away from my conversation with Shawnee, Lakota, Potawatomi, Ojibway, Algonquin, and Mohawk artist Philip Cote.

Cote was recently approached by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) to create a series of images to cover TTC vehicles and for posters on subway cars—a project that is now complete. This collaboration comes at a time when the TTC appears to be making increased efforts to centre Indigenous voices where they can, including an awareness campaign taking place this month for Indigenous History Month. Each poster highlights an Indigenous historical site in various parts of the city near existing TTC routes and stations.

You’ve probably already seen Cote’s art, as he is a renowned painter and muralist in the city with work in dozens of schools, at major intersections, and at the Fort York Historic Site. Now, this collaboration with the TTC means thousands more Torontonians will get to see his work daily.

At a glance, the design is meant to be pretty simple, says Cote. The art is described as “black and white sketches done by hand, blown up to fit the TTC streetcars, busses, and subways,” done in the popular Anishinaabe Woodlands style. Bright, bold, and two-dimensional, it’s a type of Indigenous art made especially popular in the 1960s by famous Indigenous artists like Norval Morrisseau (fun fact: Cote shared he lived down the street from Morrisseau at one time).

Cote’s designs for the murals had more than just artistic intentions. The work tells the story of Toronto’s history as Indigenous land, including a visual and written land acknowledgement created by Cote himself. The artist told me he feels a special responsibility to share these acknowledgements of history as a young elder, knowledge keeper, and activist. He intends for folks to interact with his work during their commutes so that as they ride, it may spark questions about what the art means, who it is for, and what more they have to learn. “What the real history is… I like to straighten that out,” he says.

As an Indigenous person with deep ties to the city, I can attest that there is much to learn for many Torontonians. When I’ve asked non-Indigenous people if they know what Indigenous land they’re on, I almost never get an answer. Hopefully, a visual medium will be more accessible for many people and encourage community education.

In our conversation, Cote highlighted the intentional ways he represented the First Peoples of this territory as a crucial part of his work. He created a great black Thunderbird to represent the Three Fires Confederacy (Ojibway [Chippewas], Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations), a beaver to represent the Huron-Wendat, and a script featuring the signatories of the Toronto Purchase.

Another essential part of Cote’s work is how it clarifies that Indigenous voices and teachings are not simply a part of the past, but contemporary forces of immense importance and influence. Across some of the work, Cote included the phrase: “The stories of each of these nations endure, and continue to guide our thoughts and actions on this land.”

As valuable as this art will undoubtedly be for many non-Indigenous folks, I am most excited about what this work can do for Indigenous people. More than educational, telling the story of Toronto as an Indigenous person is an essential act of rewriting colonial narratives. “Indigenous people are only ever allowed to see ourselves through the colonial gaze,” Cote said. “With this work, I tried to show the true history of this land, through our eyes and worldviews.”

Chief R. Stacey LaForme of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation shared that the Missisaugas gave input into the project and added that he’s always admired Cote’s work and commended the intention and thought behind the project. “It’s important that everybody sees themselves in the world that surrounds them,” he says. “Having displays like this where people see themselves represented is important.”

It is especially important when we acknowledge the long history of erasure Indigenous people have faced in Canada and Toronto. As Cote puts it, “Canada has always robbed Indigenous people of having a voice.” This practice of exclusion means that we Indigenous people have to work extra hard to find instances of accurate representation of sources of knowledge. Creating those accurate representations is an important step in fostering healing for our communities, Cote says.

“Colonialism affected all of us so profoundly. We all have the same deep wounds. The only way we heal those wounds is through telling our own stories our way,” the artist says.

Laforme called for even more initiatives like this. “I think it’s a great move by the TTC, and now I challenge companies like Metrolinx to step up and do the same,” he says.

When Indigenous people see themselves and their stories valued and highlighted, it is to everyone’s benefit.