Toronto is getting old. In 2016, we crossed a demographic tipping point, with more people over 65 than under 15. Since then, the percentage of the population over 65 has only ticked higher—from 15.6 percent in 2016, to 17.1 percent in 2021, to an estimated 21.2 percent in 2041, which will put Toronto in the same category as “super aged” societies like Japan, where one in five people is a senior citizen.

Aging, of course, is not an inherently bad thing; we are, all of us, older today than we’ve ever been before, and with a little luck we’ll be older still tomorrow. Nor is it exactly unexpected. But despite the actuarial predictability of the baby boomer generation chugging towards senior citizenship, it sometimes feels like the city has been caught unawares, without the necessary services or infrastructure to match that reality.

The Local’s new series, The Aging City, is an attempt to reckon with life in a city whose fastest growing age groups are all over 65. In neighbourhoods built for cars, how does our transportation need to change to allow seniors to stay mobile? What does the future of labour look like as the workforce ages—with seniors working everywhere from behind the counter of the local Tim Hortons to the boardroom? How can we change our home care system to allow people to receive care where they live, rather than in scarce hospital beds and long-term care homes?

For Dr. Samir Sinha, director of geriatrics at Sinai Health and University Health Network and director of health policy research at the National Institute on Ageing, the issue that worries him most is the one that’s most fundamental: where will seniors in Toronto live? “The big issue that keeps me up at night when it comes to aging in Toronto is that, with housing affordability becoming an issue for everybody, you can imagine how hard it’s becoming for older, lower income individuals,” says Sinha.

In that essential task—ensuring the people who have spent their lives in this city are able to keep living here—Toronto is failing. Subsidies to help people age in place are wildly insufficient. Seniors are the largest demographic on our ballooning waitlist for affordable housing, making up 41 percent at last count. Spaces in long-term care homes are also scarce, and according to Sinha, one-third of the people in those spaces in Ontario can’t even afford the basic co-payment.

When Sinha looks at the future—comparing the sheer number of aging people against the number of housing starts or long-term care beds—he doesn’t like what he sees. “I’m really nervous, to be honest,” says Sinha. “When people can’t afford to age in this city, then this is when they end up homeless. This is when they end up in our shelters.”

The story of an aging Toronto, of course, is not just a story of vulnerable senior citizens struggling to get by. No demographic is a monolith, and our cliched image of the “senior citizen”—a dated sitcom vision of cranky old men and blue-haired women with purses full of hard candies—simply doesn’t match the reality of aging in 21st century, multicultural Toronto. Many of the people becoming seniors today have accrued wealth and power during their years that they have no intention of relinquishing. The multi-million dollar homes of Rosedale and the Annex are full of seniors. Our mayor is a grandparent, as was her predecessor. Seniors vote in disproportionately high numbers and are overrepresented in neighbourhood consultations.

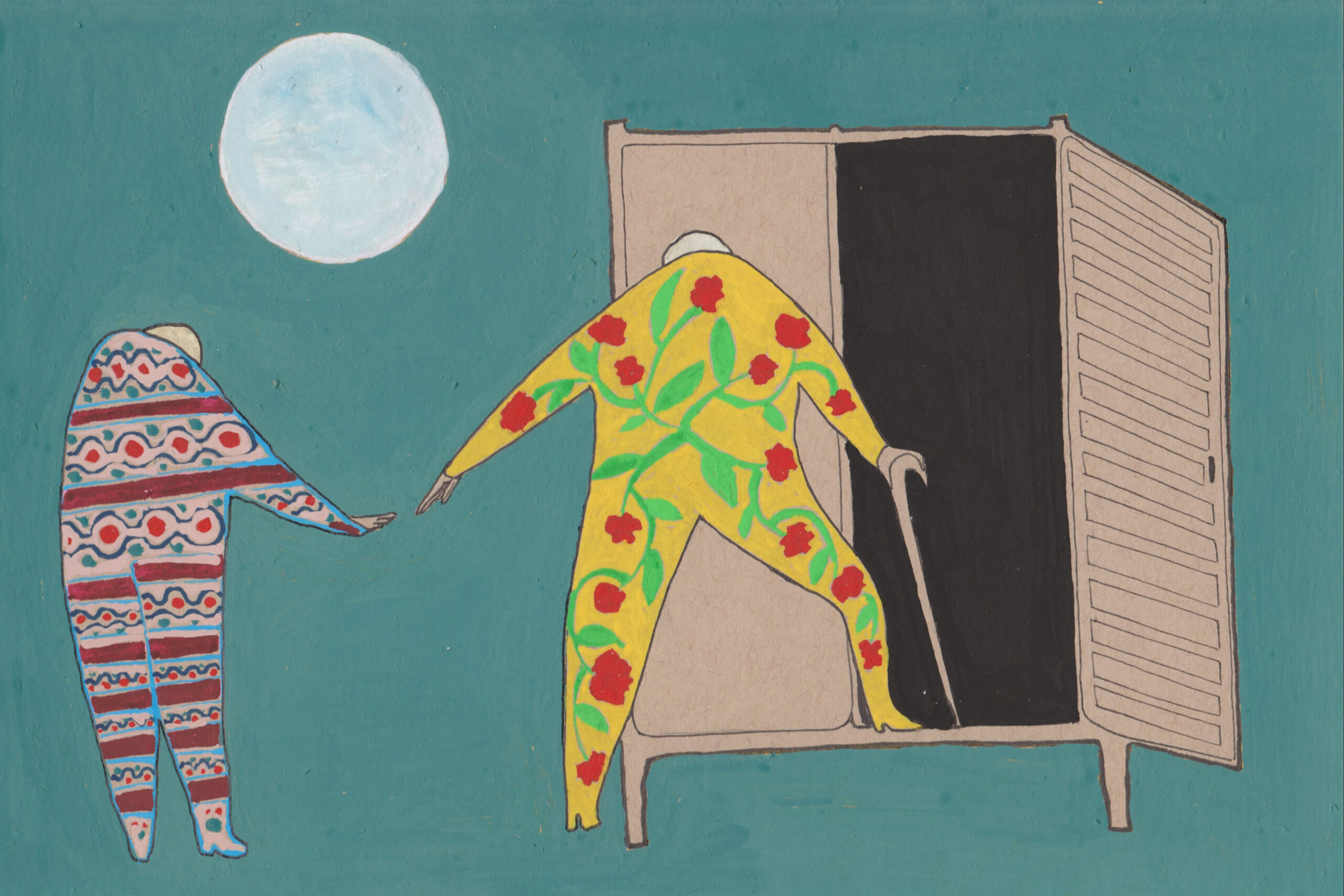

Over the coming months, we’ll dig into what life in an aging city actually looks like, and what it should look like—from a deep dive on home care to a story on the systemic issue of seniors who wander, from a personal essay about navigating the city in your seventies to a feature on the tragic phenomenon of LGBTQ2S+ seniors being forced back into the closet as they age.

The stories are vital diagnoses of how the city is failing aging Torontonians. They also offer some clear solutions. Toronto is getting old; let’s build a city that matches that reality.

Correction—December 6, 2023: A previous version of this article quoted Samir Sinha as saying that two-thirds, not one-third, of people in Ontario LTC homes can’t afford the co-payment.