For the last 20 years, the TTC was supposed to have been building a world in which, by 2025, 65-year-old retiree Jane Field wouldn’t need to worry about getting the wheels of her power wheelchair stuck in the gap between the subway car and platform. She wouldn’t need to depend on the kindness and strength of strangers to move her to safety. And she certainly wouldn’t need to read a lengthy manual on how to navigate Toronto’s transit system as a disabled rider.

But that promised future has been delayed.

“Who else has to study a 44-page textbook before they take the TTC somewhere to a doctor’s appointment, or a movie night with a friend?” she asked in an interview from her home in early November. “That right there is a big red flag for me that says something’s not really accessible here.”

By January 1, 2025, every single TTC subway station is required to be compliant with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). In other words: fully accessible. That means having Braille and tactile pathways for visually impaired riders, closing the gap between a subway platform and a train for safe boarding, and, perhaps most critically, adding functional elevators to all stations instead of stairs or “out of order” signs.

The TTC has had 20 years to meet this goal, and for most of that time, it has insisted it was on track. As recently as last year, the agency told The Local that 55 of the system’s 75 stations were already accessible, and the rest would be in time for January 2025. But suddenly, this year, the TTC announced it wouldn’t make that timeline.

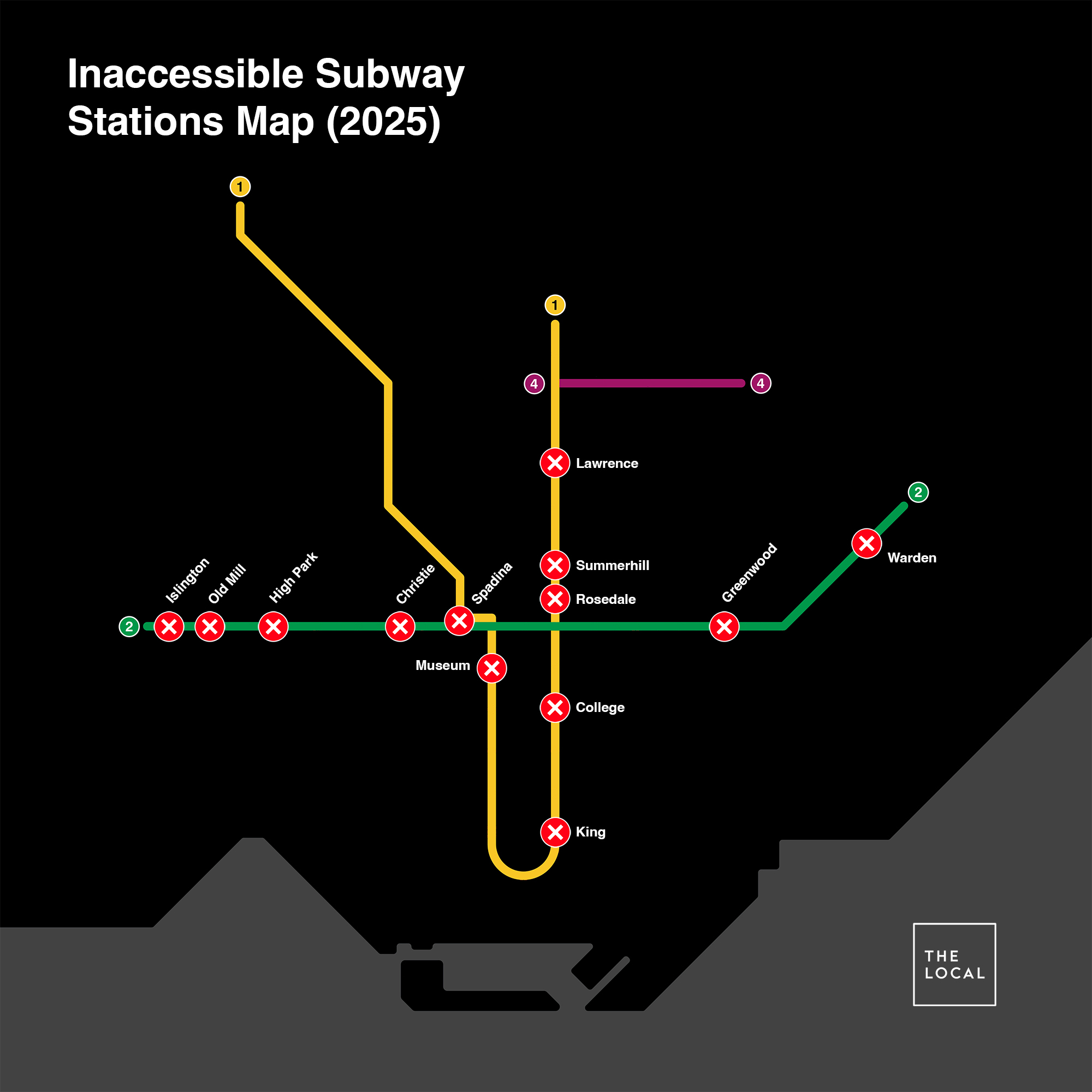

In September, TTC staff admitted in a report to the agency’s board that at least a dozen subway stations would not, in fact, finish elevator construction by the AODA deadline. Downtown stations like King, Spadina, Museum, Christie, and College are on the list, as are Islington, Warden, Lawrence, Old Mill, High Park, Greenwood, and Rosedale. (Summerhill’s completion date, according to the September update, is listed as “Q1 2025”, which may mean it hits the deadline).

“It’s very disappointing to sit here and bring this news to this board. We know the commitments that were made over the years,” TTC CEO Rick Leary told the agency board in September. “We have to be realistic with ourselves now that we’re not going to meet that mandate.”

According to the new timeline given by the TTC, nearly all of the outstanding stations will likely be finished between the spring of 2025 and the winter of 2026. The exception is Old Mill, where work on a major redevelopment project hasn’t even started. In a series of emails to The Local, as well as agency documents, the TTC blames a combination of poor capital funding, the COVID-19 pandemic, and difficulty finding skilled workers (and keeping them on the job), all coming to a head in the last few years.

For anyone who has difficulty navigating steep stairs, escalators, or ledges, these reasons are cold comfort. Anyone can be disabled, of course, but the likelihood of having a disability grows exponentially as people age. Nearly 500,000 seniors live in Toronto, according to city statistics, and in less than 20 years, that population is set to nearly double. In a rapidly aging city, missing the AODA deadline on Canada’s largest transit network means elderly and disabled Torontonians, who’ve waited two decades to freely enjoy their city, are forced to wait even longer.

The TTC’s accessibility efforts go as far back as 1990, and its current bundle of plans involve 47 different initiatives ranging from overhauling elevators at subway stations to installing tactile surfaces for visually impaired riders at bus stations. Between all of its upgrades, the TTC expects to spend a total of $1.6 billion by 2032. These include the $1.1 billion Easier Access Phase Three Program, started in 2007, to refit subway stations with elevators, alter station architecture, and replace mechanical and electrical connections.

Ron Buliung, a University of Toronto professor specializing in disability and transportation geography, says that for the most part, the TTC has put its money where its mouth is, and shown its work through publicly accessible documents. “It represents a serious commitment to accessibility retrofit,” Buliung says.

No construction project, particularly above the billion-dollar mark, ever runs exactly according to schedule. But what makes the failure to meet the 2025 deadline so striking is how long the TTC had to implement it—20 years—and that the agency seemed to have known problems were brewing long before publicly acknowledging them.

For the first seven years of this phase of the Easier Access program, the TTC seemed to make good progress. In fact, the original plan was to complete improvements by 2020 and leave five years of wiggle room between then and the AODA deadline. But the TTC’s capital budget for 2014-2023, negotiated a decade ago during Mayor Rob Ford’s term in office, cut $190 million from the project, as well as hundreds of millions for other TTC spending. In budget documents from the time, the TTC described the accessibility improvements as “very costly and mostly funded by debt.” The agency’s plan, the documents say, was to secure future funding from the Ontario government to support it.

It took two years for the TTC to receive enough money to get the Easier Access plan back on track, and staff warned the AODA deadline needed to be a priority for the agency’s capital spending going forward. But despite the apparent resolution of the funding crisis, several monthly reports from the agency’s CEOs, Andy Byford in 2017 and Rick Leary in 2018, indicated the TTC could miss its AODA deadline by nearly a year. Then, in 2019, Leary changed his tune, reporting to the CEO board that the agency was on track to hit its 2025 deadline—perhaps reflecting natural progress on the project, and attempts by the TTC to speed up its construction.

In the agency’s capital budget for 2020 to 2029, an additional $1.7 billion was set aside for infrastructure projects, including $528 million for phase three of the Easier Access project. However, the capital budget from 2020 shows the project was still missing a total of $280 million in necessary funding over a 15-year period. All of that money was expected to come after the 2025 deadline.

The lack of transparency, of answers, and the sudden announcements going back and forth on the deadline, hasn’t inspired confidence among disability advocates. David Lepofsky, chairperson of the AODA Alliance, a disability consumer advocacy group, remembers listening to a 2017 presentation by Byford in which he declared the TTC would be fully accessible by 2025, garnering applause. That statement seems suspicious to him now. “So the question is—were they lying then?” Lepofsky says. “Or did something happen between then and now? And if so, what was it?”

What makes the failure to meet the 2025 deadline so striking is how long the TTC had to implement it—20 years—and that the agency seemed to have known problems were brewing long before publicly acknowledging them.

In a statement from the TTC to The Local, a spokesperson for the agency pointed to a number of snags that forced it to miss the AODA deadline. “As most people will appreciate, what we’re undertaking is a large and complex task,” they wrote.

Most of the early stations to receive upgrades were simpler than the ones the TTC are undertaking now, with the spokesperson pointing to the complexity of the grade-separated bus bays at Warden and Islington as an obstacle to elevator upgrades. But TTC staff had warned about backlogging complex projects as early as 2016, saying in a report that the budget for this phase of Easier Access was based on “less complex earlier projects,” and that the actual costs would be much higher due to access and property rights issues.

The TTC also didn’t have enough money, despite the hundreds of millions committed in 2016. “Prior to 2020, we simply didn’t have the capital funding in place to complete the program,” the statement said. The pandemic didn’t help, affecting material costs and the capacity of city bureaucrats to approve building permits. Neither did the rise in construction material costs and labour strikes in the years following, according to the TTC statement and public documents.

The result, unless construction timelines improve dramatically, is a blown deadline in contravention of provincial law.

“That’s why we’re here today, giving you 16 months, not showing up last minute,” Leary told the TTC board in September. “We’ve tried to give advance warning.”

Given that this phase of Easier Access launched in 2007, and that the TTC reported it still had 20 stations to go as of last year, The Local pressed the TTC on when they realized they wouldn’t be able to hit the deadline. The spokesperson simply replied: “This year.”

The TTC’s September report promises to start an “interim service” plan for all TTC stations that remain accessible beyond the AODA deadline date. That may include bus service to and from nearby accessible stations, a stopgap that simply may not be tenable for many elderly or disabled people given the state of TTC delays today, as well as Toronto’s infamously bad traffic.

At the provincial level, there are no apparent consequences for missing the AODA deadline, which calls into question the efficacy and point of the deadline altogether. We contacted Ontario’s Ministry of Transportation for comment. It declined, but recommended we contact the Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility, which is responsible for enforcing accessibility laws. No one responded to multiple emails requesting an interview about the TTC’s admission it would miss the AODA deadline.

Activists on the frontlines of the accessibility movement have also been shut out. Lepofsky—who is also a lawyer, and the reason there are audio announcements on subways and streetcars—hasn’t heard anything. The AODA Alliance used to have extensive dealings with past Ministers of Seniors and Accessibility. Since Premier Doug Ford’s last election, the organization has heard nothing. “The minister’s office does not answer emails or letters from us,” Lepofsky says.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

Despite all its efforts, the TTC remains woefully inaccessible to many riders, including at some stations that the transit authority has already retrofitted. “We’ve got stations—new ones—that have all sorts of accessibility problems that were totally avoidable,” Lepofsky says. Installing working elevators at all subway stations is a necessary starting point, but accessibility doesn’t end there.

“Even when things are technically accessible or legally accessible, that doesn’t mean they’re functionally accessible,” says Léa Ravensbergen, an assistant professor at McMaster University who studies sustainable and equitable transportation.

Once on the platform, a new crop of issues emerge for elderly and disabled people. Crowds and a lack of seating make subways unmanageable for seniors with difficulties standing. And some platform designs can be potentially dangerous for those who are blind. York University station, for example—which opened in 2017, has working elevators, and is technically considered accessible—trains run on both sides of the platform. As Lepofsky explains, inadequate space between the walls and platform edges mean cane users can’t safely use the walls as guides. This issue, he says, along with crooked railings, and poorly designed tactile wayfinding tiles, which are supposed to help visually impaired cane users avoid stairs and platform edges, can make even new stations impassable for disabled people.

The delays in accessibility are particularly troubling when placed in the context of the TTC’s “Family of Services” (FOS) system. Under FOS, the transit authority planned to force some users of Wheel-Trans, the city’s door-to-door paratransit system, to integrate city transit into their journeys, shuttling riders to bus or subway stations, rather than door-to-door. The problem is, of course, that riders with access needs are potentially being taken to inaccessible stations.

As of last year, the TTC had plans to begin making Family of Services mandatory this year—but in what appears to be a reversal of their prior decision, the TTC said in a November statement to The Local that the system isn’t mandatory, and that there are no plans to make it so. A closer look at the paratransit policy, however, reveals that some riders will only be granted door-to-door services under specific conditions (like snowy weather, for example). Outside of those conditions, regardless of need or preference, they’ll have no choice but to navigate the TTC for portions of their trip, rendering the policy essentially mandatory in all but name.

Experts say the consequences of an inaccessible TTC system aren’t just a lack of mobility. For riders unable to access Wheel-Trans, or who find themselves pushed out of door-to-door service through the Family of Services overhaul, simply traveling around the city can be impossible, leading to health consequences. As residents of the city get older, “we know that physical activity is one of the biggest things that helps us stave off all these chronic conditions,” says Marla Beauchamp, an associate professor at McMaster University’s School of Rehabilitation Sciences. “So heart disease, and high blood pressure, and diabetes, and all those conditions that pile up on one another.”

The act of traveling to or from a transit station, whether by cane or walker or wheelchair, also keeps loneliness at bay. Visiting friends and family is a critical way to feel connected to the world beyond your door. The TTC has promised hundreds of millions of dollars in accessibility investment, but much of the system still isn’t equipped for disabled riders, and in the absence of accessible transit or a friend with a driver’s license, some people are effectively confined to their homes.

If Field, a Wheel-Trans user, hadn’t won unconditional access to door-to-door service, she’d probably be in that boat. When she was required to re-register for Wheel-Trans last spring, Field told the TTC appeal board overseeing her case that putting her on the regular subway system would ruin her life.

“I don’t feel confident and able to go out and take the subway independently,” she recalls saying. “It will affect my ability to go out in the community, and take part in activities. So it’ll affect my mental health. It’ll isolate me. It’ll totally isolate other people who can’t fight the system.”