Edward Chan, an 81-year-old retired accountant, had his routines, and one of them was to leave his condo near the Scarborough Town Centre, drive to one of his favourite restaurants, and pick up lunch for him and his wife, Mae. They both loved to eat but Mae had lung issues, and getting out of the house could be a challenge. Takeout was a necessary treat. Edward usually did this a couple times a week. He was normally gone no more than 15 or 20 minutes. (Edward and Mae’s names have been changed to protect their privacy).

But by the spring of 2019, those trips started to take longer and longer. He would get distracted, wander into a Canadian Tire or something, and be gone for more than an hour. On one worrisome occasion, while out in the car, he vanished for six hours. One June morning that same year, Edward went for a walk in the condo’s garden. When he hadn’t returned after an hour, Mae went down to look for him. He wasn’t there. She checked to see if their car was in the parking lot. It wasn’t. He had taken his cell, but when Mae called, he didn’t pick up.

This wasn’t unusual—Edward is hard of hearing and often misses calls—but by 1:00 p.m., Mae was getting concerned and called their daughter, Jennifer, a real estate agent. Jennifer urged her mother to call the police, but Mae was reluctant to involve them. At one point, Edward called Mae from a Swiss Chalet, but didn’t say which one and then promptly hung up. Jennifer called all the Swiss Chalet locations in the area. Nobody remembered him. She called the other restaurants he normally frequented, but again, no luck.

Finally, around six that evening, Jennifer persuaded Mae to let her call the police. But when they asked to come to the condo to get more details and a photograph, Mae resisted. “He’ll learn his lesson,” she told an exasperated Jennifer. “He’ll come home.” By 11 p.m., with no sign of Edward, Mae finally relented and the police issued a news alert.

A couple hours later, Jennifer’s phone rang. It was Edward himself. He was still in the car, but he had a flat tire and had pulled off the road. He had no idea where he was. Jennifer told him to stay inside the car, and the police eventually arrived. Edward had made it as far as Pickering, roughly 15 minutes away, but it was impossible to know where he’d been before that, or how long he’d been driving on the flat. However long it was, the car was so badly damaged it was no longer operable.

Edward had obvious cognitive impairment, but he wouldn’t be officially diagnosed with dementia until 2022. Between 2019 and then, however, there would be several other incidents, of various gravity and danger. He’d heat up cooking oil in a pan on the stove and walk away. He’d get off on the wrong floor in the condo and try to get into a unit that wasn’t his. After the flat-tire incident, his driver’s license was taken away, but on at least one occasion, he tried to get into a stranger’s car using his house key.

Jennifer and her sister eventually deployed a number of safeguards. They hired a personal support worker to take him for walks a few times a week. They put a tracker on his keys. They installed an Echo Show in their parents’ living room, essentially a two-way camera-phone device that would allow them to “drop in” whenever needed.

The solutions weren’t cheap, however, and the vigilance was exhausting. It was all perhaps most painful for Mae—Edward had so long taken care of her, and now not only could he not do that, he was also, as a husband, as a human being, gradually, inexorably slipping away from her. “I’m sure it’s very difficult for my father,” Jennifer says, “but dementia is one of the few illnesses that’s harder on a person’s loved ones than the person themselves.” They finally put him on a waiting list for long-term care.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

Despite the turmoil and fear that accompanied each of these close calls, the Chans were lucky—each time, Edward eventually made it back home safely. Other seniors have not been so fortunate. Last October, three Torontonians in their 60s and 70s got lost, and ultimately went missing, over the course of two weeks. One of them, a 76-year-old woman named Tulip, was found dead after a week-long search. Seventy-three-year-old Desmond, who lived with dementia and Parkinson’s, was also found dead at the end of November. By the beginning of December, another half-dozen seniors had been reported missing by the Toronto Police Service, with half of them still not located as of this writing. In 2023 as a whole, 555 people 65 and over were reported missing to the Toronto Police. The year before, there were 663.

These tragedies tell just part of the story. The Alzheimer Society of Canada estimates that 60 percent of people with dementia-related memory problems will get lost at some point. But the vast majority of these incidents will never be reported to the police at all. A senior might simply be sitting at a coffee shop, unable to remember why they’re there or where they should go next. They might get up to go to the bathroom and then mistakenly walk out their front door, locking themselves out in the dead of winter. Others still, compelled by a memory of their former lives, may travel for several kilometres to a workplace they haven’t been to in decades. They could be lost for just an hour or an afternoon, but there is a grave urgency to all these cases—if a person with dementia is missing and not found within 12 hours, there’s a 50 percent chance of injury or death.

As Toronto’s population ages, the number of these crises is only going to grow. According to the Alzheimer Society, more than 1.7 million Canadians could have dementia in just over 25 years, with Ontario expected to experience a 200 percent increase between 2020 and 2050. That’s a lot of people who will very likely get lost, probably at least more than once, with enormous, sometimes uncertain, consequences for governments, our systems of care, and law enforcement agencies. As Jennifer Chan puts it, “It’s a tsunami that’s going to be coming.”

The problem of seniors going missing has long been an issue, but according to many experts, the situation is getting worse. “We are now just starting to understand what the numbers are,” says Lili Liu, an occupational therapist who heads up the University of Waterloo’s Aging and Innovation Research Program (AIRP). “But the numbers are increasing.” Liu chalks this up to a few things. Better education and awareness means a missing person is more quickly reported now. There’s also a greater likelihood of people going missing in large urban centres like Toronto, where there’s more anonymity and people are less likely to be noticed being out-of-place. But the biggest reason is the most obvious one—Canadians are living longer and our population is rapidly aging. The oldest of the baby boomers, a cohort comprising 25 percent of the population, are hurtling towards their 80s. “The number of seniors is increasing,” says Liu, “and we know that age itself is a risk factor for the development of progressive dementia. And with progressive dementia, getting lost or going missing is a risk for everyone who has it.”

Although Canada released a National Dementia Strategy in 2019, the country’s still not adequately prepared for this demographic shift. In 2022, CanAge, a national seniors’ advocacy organization, published “Dementia in Canada,” the first independent report to comprehensively assess how ready the country is for the tsunami Jennifer Chan predicts. In their view, all we’ve done, for the most part, is stockpiled some sandbags. On just about every front, from the number of geriatricians in the country to collaboration between different levels of government, we continue to fall short. As Laura Tamblyn Watts, the organization’s CEO, argues in her introduction to the report, “We are running out of time.”

Time, but also resources. As Edward Chan’s story amply illustrates, helping both loved ones and caregivers navigate the challenges of the disease can be complicated, expensive, and emotionally draining. And there’s no one-size-fits-all fix. As Victor Kwong, a Toronto police officer who is also the co-founder of Memory and Company, a respite hotel and daycare for seniors with memory issues, puts it: “If you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia.” The disease alters each person’s brain unpredictably, and at different speeds, with different effects. One person might lose the power of speech; another may be able to speak perfectly well but be completely free of inhibition.

Faced with these challenges, however, a number of people are doing their best to help reduce the number of seniors who go missing. Waterloo’s Lili Liu and her team are currently researching better technological solutions and, equally as important, developing a national coordinated strategy for collecting data on persons with dementia who go missing. For several years, Liu has worked with Ron Beleno, a Scarborough-based consultant and entrepreneur who spent a decade taking care of his father, Ray, who was diagnosed with dementia in 2007. Like Jennifer Chan, Beleno improvised a system of protective mechanisms and procedures—door sensors, cameras, handing his business card out to restaurants that Ray frequented. “My goal was not to lock my dad up in the house,” Beleno says, “but to keep him in the community.”

Community was the key word. Too often, the aged are almost invisible in Toronto; the enormous loss of life in long-term care homes during the pandemic’s early days horrifically exemplified this. But the more people are made aware of vulnerable residents, the more eyes on the street, as it were, the safer those residents will theoretically be. Nine times out of ten, the public finds a missing person before police or search-and-rescue teams do. A couple of tools currently exist to amplify this: the Toronto Police Service has a Vulnerable Persons Registry, a voluntary database that provides critical information to first responders about community members who are cognitively impaired or otherwise vulnerable; Waterloo’s AIRP has created a website, Canadian Safe Wandering, with tips and tools that assist seniors in safely exploring their communities.

Along these lines, in 2015, Beleno and Liu began developing a localized alert system they called Community ASAP. For years, pundits and politicians have called for a “silver alert” system, comparable to the AMBER Alert used for missing and abducted children. While such alerts are used in many American states, there’s been reluctance to adopt one in this country, partly because so many seniors wander and get lost there’s fear that Canadians would soon grow numb to its use. Community ASAP, meanwhile, is extremely targeted and hyperlocal: volunteers who sign up can select up to five neighbourhoods that they normally frequent; if an older adult goes missing in one of those neighbourhoods, all the volunteers who’ve agreed to monitor that neighbourhood receive an alert and description of the missing person. If they spot the individual, they can then notify first responders.

There was much enthusiasm for Community ASAP, and the system was tested by, among others, Toronto police. But it has yet to get off the ground, and Liu and Beleno have since shifted their focus to additional technologies. Having begun their research with wearable devices that have GPS locators built into them, Liu says she and her team are now focused more on software than hardware. Beleno, for his part, is now working with WeTraq, an AI-powered assistive technology firm, and Silverts, an adaptive clothing company, to create an insole with three different types of locating technologies embedded in it. “Alert systems are great,” Beleno says, “they’re a big part of the conversation. But there’s much more that can be done as well, from high tech to low tech, community, education.”

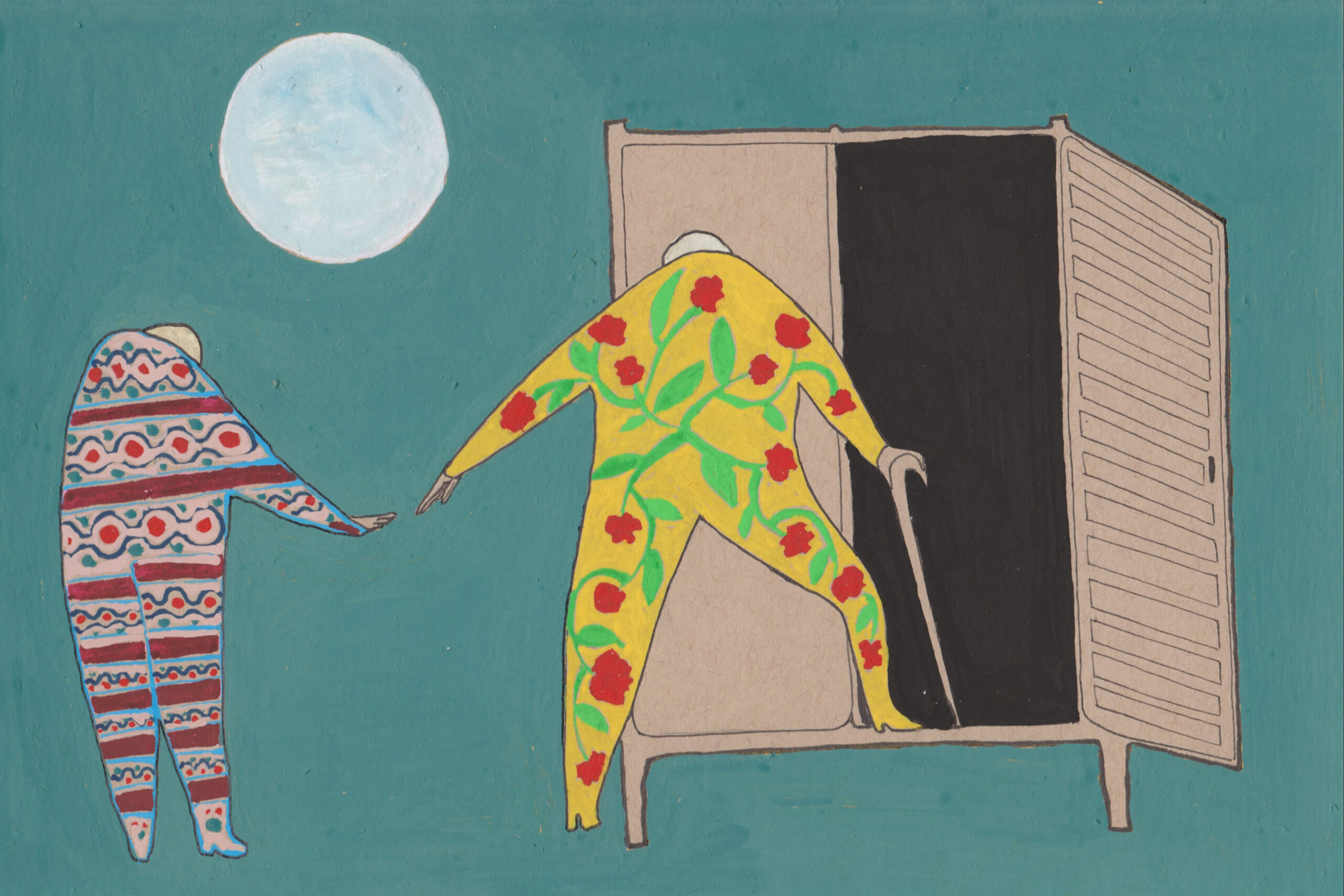

Memory is the locus of our identities, the seat of our souls. Acknowledging its deterioration is also an acknowledgement of the imminent, bewildering disappearance of those very things.

A significant hurdle in Community ASAP’s widespread adoption was also, in Liu’s words, the “bureaucratic” process through which such alerts are issued. First, a family has to report the person missing, which can take time. Then the police need to visit loved ones to obtain a photo and information about the person. When someone goes missing in Ontario now, only that person’s first name and age is included in the alert issued by police, accompanied by whatever identifying details the person’s loved ones want to make public. This is done to theoretically protect the missing person, so that they won’t be forever associated with this particularly unpleasant moment in their lives, or they won’t be publicly exposed as a vulnerable person and possibly exploited in some other way. Both these things sound good, but they can also hinder a search. “Privacy legislation is a barrier in some of these cases,” Liu says. “We want to protect individuals’ privacy and their own vulnerability—by releasing publicly their identity and their description, we can put them at risk. On the other hand, if we don’t release it, then the extra eyes on the ground aren’t able to help.”

A related impediment currently is that the data which police services across the country gather are inconsistent and disjointed, and those services only rarely share that data with other agencies. Very few even have a specific category to describe a missing individual as having cognitive impairment or dementia; often, they’ll use a catch-all like “mental health” or “depression.” The Toronto Police Service’s Victor Kwong acknowledges this, but points out that the police are also, again, limited by the information families provide about a missing person. “We only have what we’re given,” Kwong says. “Some families will not say that they have dementia. They’ll just say, ‘Oh, Mum’s a little forgetful.’”

This hesitation, or avoidance, or denial—call it what you will—is at the heart of the problem. More so than most diseases, dementia carries great stigma. “Stigma is an overarching problem which blocks progress at every level,” CanAge’s Tamblyn writes. It made Mae Chan slow to call the police when Edward went missing. It makes vulnerable people afraid to acknowledge their diminishing capacity. And it makes families all over the country slow to get their loved ones treatment or make accommodations.

My own father is 77, and for the last year, has been exhibiting signs of mild cognitive impairment. I’ve been in the car with him when, in the middle of the day, he didn’t notice a jogger on the road in front of him, almost hitting her. Around the same time, I noticed that he’d put up Post-its in the bathroom, reminding himself to brush his teeth. During his recovery from recent hip surgery, we sat together watching Netflix in the living room. Searching for a movie, he needed me to tell him its title three times in less than a minute. Finally, he just handed me the remote.

Conversations about his failing memory, however, don’t go very far. I gently rib him or, occasionally, request that he maybe talk to his doctor. He laughs meekly, changes the subject. And it’s difficult to know, however, how seriously to take it. Doesn’t everybody’s memory start to falter after a certain age? Don’t we all misplace things, forget dates, mix up names? It seems inevitable that our brains will, as we age, lose some of their capacity, just like we lose muscle strength and bone density. It’s also obviously much more difficult to talk about our brains giving out than our hips or knees. Memory is the locus of our identities, the seat of our souls. Acknowledging its deterioration is also an acknowledgement of the imminent, bewildering disappearance of those very things.

But acknowledgement and acceptance, by both the person afflicted and their families, are imperative if that person is to stay safe. “The first thing I tell people when they’re diagnosed with dementia is accept,” says Paul Lea, a self-described dementia advocate in Etobicoke who was himself diagnosed with the disease in 2009. “Accept the circumstances, the consequences, and the difficulties you’re going to have because you are going to have difficulties. Don’t be afraid to say that you’ve got dementia.” As a bulwark against his own confusion, Lea plans his travels—to grocery stores, to the doctor—in great detail, keeping to known routes but also rehearsing them beforehand on Google Street View. One time, however, he deviated from his route, and found himself on a street he didn’t recognize. He sat down on the sidewalk and stayed there for two hours, until a kindly passerby finally stopped. When Lea told him what was wrong and that he just wanted to go home, the person managed to get him there easily—Lea’s house was only three blocks away.

This past March, Edward Chan moved into the Mon Sheong Home for the Aged, a Chinese-language long-term care facility near the Art Gallery of Ontario. He’s alone for the moment, but it’s expected that Mae will eventually join him there. It’s been an adjustment. While the staff have been good to him, and they offer a number of activities, he still grumbles. “He says he’s lost his freedom,” Jennifer says.

That raises a related question—what makes a person wander in the first place? While the disease distorts and batters our conventional understanding of time and space, a persistent, primal need for human connection remains. Indeed, experts say, most often people wander simply because they lack meaningful activity, engagement, and interaction. The pandemic obviously made socializing difficult and strange for everyone, but for no one so much, perhaps, as our oldest friends and family members. During lockdown, the numbers of wandering seniors spiked. Lacking their usual time with family and friends, or stimulation of any kind, many older adults set out in search of it. Paul Lea puts it more bluntly: “They just want to get out. The COVID business the last couple of years has kept them indoors and they just want to get out and walk around.” COVID aside, isn’t that what most of us want? To get outside, of our homes and our bodies and brains, to be with other people, in other environments, to see and hear and feel new things for as long as we can? Together, we just have to make sure everyone can do this, and still get safely home.