Jane Rowan could’ve driven to Ottawa in the time it took Wheel-Trans to transport her from North York to Etobicoke and back.

Rowan, 78, uses Wheel-Trans, the TTC’s paratransit service, to visit her 98-year-old mother at her retirement home every other week. But when she tried booking a trip one day in June 2021, their regular door-to-door service was fully booked. Instead, she was offered a Family of Services (FOS) trip—a service that transports users via a combination of Wheel-Trans and conventional transit like buses, streetcars, and subways.

With no alternative, Rowan—who uses a cane, and whose bad knees make it difficult to stand for long periods or climb on and off vehicles—opted for FOS. “It’s not something I would do again,” she says of the trip. Wheel-Trans picked her up from her home and, on an inefficient route planned by the TTC’s software, took her to Woodbine station, six stops east of her nearest station and in the opposite direction of her destination. From there, she rode the subway across the city to Jane station, where she was picked up and driven the rest of the way by another Wheel-Trans vehicle.

The journey, which takes only about 30 minutes using the door-to-door service, took more than an hour and a half, and involved walking across subway concourses, climbing stairs, and standing outside for long periods. “My knees were killing me,” Rowan recalls. “And it felt like I would collapse.” With the retirement home’s COVID restrictions, Rowan was only able to visit her mom for an hour. Her trip home followed the same path and took even longer—two and a half hours. She arrived home exhausted and in pain, and had to lie down for the next few hours.

“The next day, I couldn’t do anything,” Rowan said. She was furious with the TTC.

Rowan first applied for Wheel-Trans in 2017 and was granted conditional eligibility—a status that means she only receives paratransit service for parts of her trip, or only under certain conditions. For Rowan, those conditions are winter weather. Like all conditional Wheel-Trans users, she still has the option of using the door-to-door service when rides are available, since the FOS program is currently optional. But Wheel-Trans plans to make the FOS program mandatory for some users beginning in 2023. For Rowan, this means she’ll eventually only have door-to-door access during winter months—otherwise, she’ll have no choice but to use FOS.

It’s a move that one critic describes as “fatally flawed”: thousands more elderly and disabled people like Rowan will soon be restricted from full door-to-door services and will be forced to navigate an inaccessible and unreliable system of paratransit vehicles, buses, subways, and streetcars.

At its heart, the FOS program is a cost-cutting effort in the face of the TTC’s straining budget—but at what cost to riders? Some users and advocates feel that the program should be made voluntary, and others argue that Wheel-Trans should scrap it altogether. But all of them question whether an organization that prioritizes savings over accessibility will actually be able to provide accessible, reliable transit for its more than 44,000 users, each with their own unique needs.

At its heart, the FOS program is a cost-cutting effort in the face of the TTC’s straining budget—but at what cost to riders?

The shift to FOS is a bureaucratic response to a basic math problem: the number of people eligible for Wheel-Trans keeps growing, while the budget remains relatively flat. In the years before the pandemic, there were an average of nearly 4.1 million Wheel-Trans trips per year; given Toronto’s aging population, that number is expected to grow significantly in the future. And when the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA)—legislation meant to develop, implement, and enforce accessibility standards—takes full effect on January 1, 2025, it will expand the eligibility for Wheel-Trans to include people with cognitive and sensory disabilities, which the TTC expects will further increase ridership by 20 percent.

The FOS program is supposed to help manage this growing demand for paratransit services and meet the eligibility requirements of the AODA. But it is also a means to help address the TTC’s financial woes caused by rising costs and stagnating ridership. Despite receiving financial aid from the federal and provincial governments, the commission is still facing significant funding shortfalls. On the municipal level, city council has repeatedly failed to raise the TTC’s operational budget by increasing taxes. In 2019, a motion filed by Toronto councillor Mike Layton to implement a personal vehicle tax, which would’ve helped fund the TTC, was voted down by the council.

Wheel-Trans door-to-door trips are expensive for the agency: the TTC subsidizes each ride by $30, versus $1 for each trip on conventional transit. Wheel-Trans’ gross operating budget was over $133 million in 2022, about 6 percent of the TTC’s operating budget.

FOS, created in part to cut costs, classifies users into one of three categories: unconditional, temporary, or conditional, which determine whether users have door-to-door access at all times, for a specified period (like for the duration of an injury) or for parts of their trip or only under specific circumstances, like rush hour or winter conditions.

When the program was announced, Wheel-Trans estimated that the resulting annual savings would be about $39 million, though in reality, the average annual savings between 2017 and 2021 was about $13.1 million. The discrepancy is due at least in part to a decrease in ridership during the pandemic, and a resulting decrease in associated costs.

David Lepofsky, a retired lawyer and chair of the AODA Alliance, a disability consumer advocacy group, has opposed the FOS program from the beginning, repeatedly calling on the government to eliminate the program.

“It takes kind of an ice-blooded bureaucrat to think of this and then to call it an improvement for people with disabilities,” he says.

Lepofsky, who is blind, led the coalition that campaigned to win the enactment of the AODA in 2005. The FOS program, he says, goes against the spirit of that act—it only moves the TTC further away from full accessibility, at a time when Ontario is less than two and a half years away from the AODA’s 2025 requirement of being fully accessible.

The FOS program is part of a ten-year strategy, first laid out in 2016, to move half of all Wheel-Trans users off of door-to-door services by 2025. The 50 percent diversion target has led some users to jokingly refer to FOS as “forced onto subway.”

“Coming up with a stat cruelly subordinates people with disabilities’ needs without regard for their actual abilities,” Lepofsky says.

“[TTC] is a mass transit provider—they are not an individual care provider with expertise in assessing individual abilities.”

To Shelagh Pizey-Allen, executive director of grassroots transit advocacy organization TTCriders, the diversion target makes clear that the FOS program isn’t about improving transit accessibility, but about kicking people off door-to-door service.

“It really affirmed what activists and people with disabilities have been saying, that they feel like they’re not being listened to—that they need full door-to-door Wheel-Trans service but they’re being denied it,” she says. “This is just about cutting the cost of Wheel-Trans.”

Dean Milton, who is leading the FOS Initiative at Wheel-Trans, says that their focus is “providing customers with trips and getting the type of service that a customer requires and can use for that particular trip.” He adds that FOS will help ease pressure on Wheel-Trans’ door-to-door services while offering customers who can ride the conventional system more options and flexibility. The rollout, he says, will be slow and calculated.

While it’s expected that annual savings will increase when the FOS program becomes mandatory for some users and they lose door-to-door services, Wheel-Trans has no exact numbers on projected future savings.

To have a reliable and accessible FOS program, you need a reliable and fully accessible conventional transit system.

55 of the TTC’s 75 subway stations are now accessible, according to the TTC, and they are on track to make the remaining stations fully accessible by the AODA’s 2025 deadline. But users point out that the accessibility of a station can change as elevators are prone to breakdowns, forcing disabled users to take long detours to reach stations with functioning elevators. This issue could be resolved with secondary elevators, but not all stations have secondary elevators, including York University station, which opened in 2017.

Chris Stigas, formerly a member of The Advisory Committee on Accessibility Transit (ACAT), used to routinely receive complaints about conventional transit from disabled users, the most common of which was safety. The TTC made promises to ACAT members years ago, according to Stigas, that they’d address this issue by positioning customer service agents on subway platforms to assist users with disabilities. But Stigas says, “I have never seen a customer service agent on a subway platform, and I’m on the subway platform multiple times a day.”

Stigas, who uses a wheelchair, requires extra runway when boarding the train so that his wheelchair can gain enough momentum to get over the platform gap—but in the crush of high-traffic hours, other riders often don’t give him enough space, resulting in several instances when Stigas has gotten stuck in the gap. Customer service agents could prevent this issue, alerting other riders to Stigas’ presence and giving him the necessary space, or helping users with disabilities in many other ways, like during emergencies or service disruptions.

Despite the TTC’s commitment, most users interviewed for this story don’t recall ever seeing customer service agents on TTC platforms. For those who did, sightings were very rare.

The TTC says customer service agents are available at eight stations along Line 1, adding that additional staff are deployed during rush hour and that they plan to roll out more customer service agents.

The TTC has also begun removing guards on subway trains—the staff formerly responsible for operating the doors and ensuring that all riders have safely boarded and exited the trains. Instead, the driver is now tasked with monitoring both the opening and closing of the subway doors via a four-camera system and the train controls.

For blind, visually impaired, elderly people, and wheelchair users who require extra time to board the train, the removal of the subway guard poses a barrier and a safety hazard, especially during rush hour.

“How is [the driver] going to critically look at [all four] cameras and determine that there’s a person with a disability, visible or invisible, on the platform who needs a few extra seconds to board?” Stigas asks.

He finds the TTC’s plans to remove the subway guard especially concerning considering that the FOS program will soon force thousands of disabled users to ride the subway. “You’re putting more people with disabilities on conventional transit, but you’re pulling labour.”

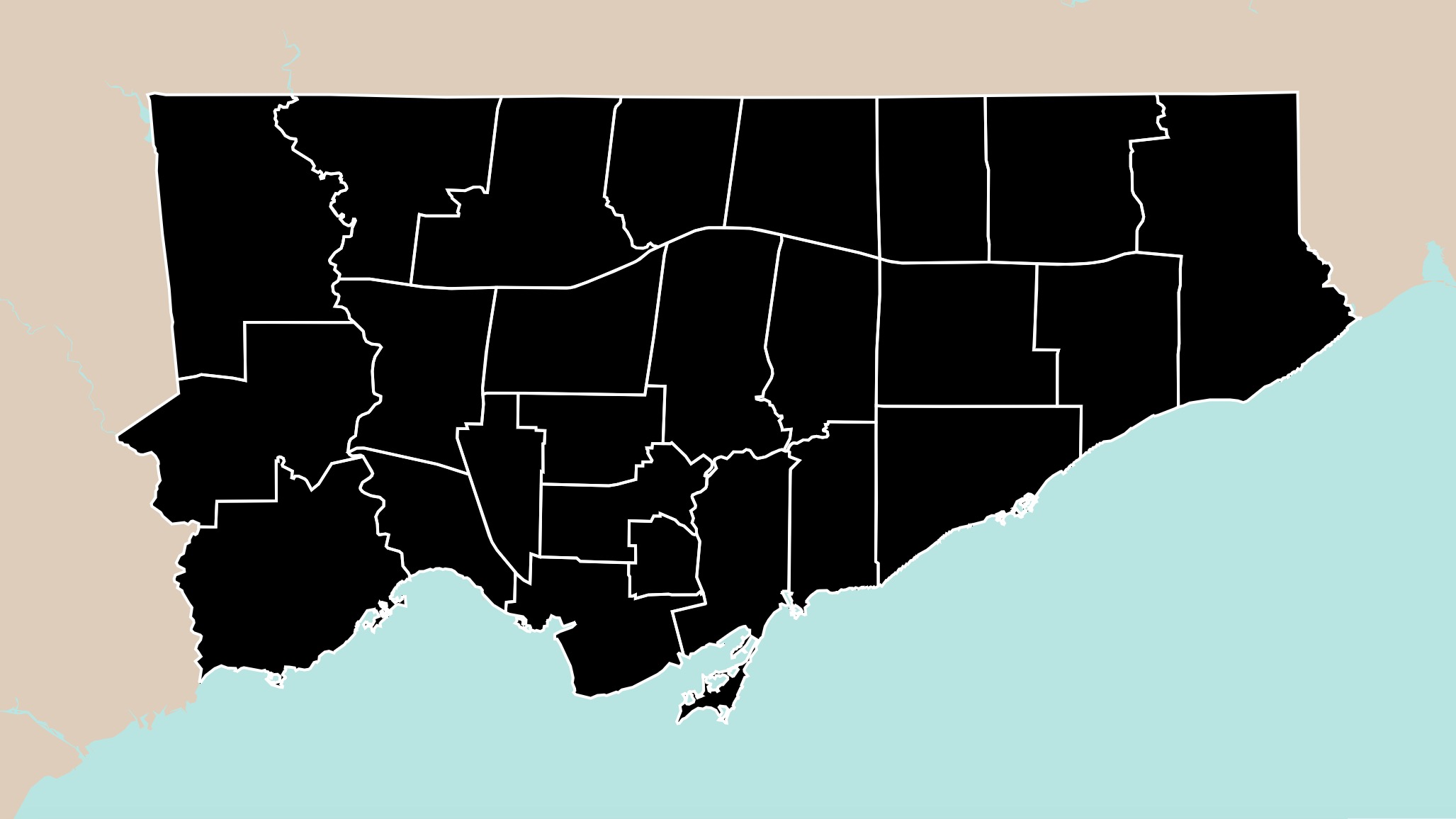

Learn More About Your Candidates

The Local’s Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked information about all candidates on the ballot for October 24’s election.

A successful FOS trip also hinges on seamless logistical harmony between conventional transit and Wheel-Trans shuttle services—an unrealistic, perhaps impossible expectation for a paratransit service that has been known to fail its users even on standard door-to-door Wheel-Trans trips, and in a broader system where even non-disabled riders are regularly encumbered by delays.

Wheel-Trans user Ramla Abukar, who is blind and uses a cane, once had to wait 40 minutes to be picked up by a Wheel-Trans vehicle, only to call the Priority Line and find out that her driver had come and gone without notifying her. Abukar was frustrated—her driver had access to her record, which stated that drivers needed to get out of their vehicles and notify her upon arrival. Wheel-Trans offered to send her another ride, but it wouldn’t arrive for another two hours. Instead, Abukar had to spend $30 on an Uber.

All of the blind and visually impaired users interviewed for this story described experiences in which their drivers left without notifying them. They all have conditional eligibility but refuse to use FOS because of the anticipated barriers associated with transferring, as well as the challenges of navigating stations that they’re unfamiliar with or that are under construction.

When a user experiences a disruption while riding the subway, they have no way of directly contacting the driver responsible for picking them up at their transfer point. They are told to call the Wheel-Trans Priority Line, which they can only do if they are above ground, and even then there are often long hold times, anywhere from two to twenty minutes. If their driver leaves before they arrive, they can request a new ride, but that can take up to a couple of hours. In these cases, many customers pay out of pocket for ridesharing services like Uber and Lyft, which can be very costly, especially for single users on Ontario’s Disability Support Program who are living off of $1,227 per month.

“They need to do a better job of mapping out the routes,” former ACAT member Sam Savona says. “If they do that, I think [FOS] will work ok.” During one trip, Savona was picked up from his home near Carlton and Church by a Wheel-Trans vehicle and was dropped off at Bloor and Yonge. He then caught the westbound train to Kipling, where a driver was waiting for him—the same one who dropped him off earlier. The driver was baffled, “Why didn’t I keep you on the bus?” They both laughed at the irony: the FOS program was intended to improve efficiency.

Savona is also one of many riders who can’t safely use FOS under all circumstances—he can’t ride his electric wheelchair in the rain because of its risk of short circuiting. Wheel-Trans has attempted to address this issue by giving those users “conditions” when they can still access the door-to-door service, like morning and evening rush hour, summer, winter, while travelling alone, or for life-sustaining treatments. But the online booking system isn’t capable of tracking the weather forecast. There is no condition for “rain,” Savona points out; instead, he was instructed to call the Priority Line on the morning of his trip whenever it’s raining to see if there’s a door-to-door trip available. Often, there isn’t, and he has to cancel his trip altogether.

Milton acknowledges that there have been growing pains with the rollout of the FOS program. He says Wheel-Trans’ goal is for their staff to be on top of service delays and to be in touch with the customer and drivers to reschedule trips on the fly, something they plan to have in place before FOS becomes mandatory.

“We know that it’s possible that at any given time, there could be some service issues…and there could be some inefficiencies in terms of a route, and we want our customers to tell us about it so that we can investigate it and make the necessary changes.”

“It takes kind of an ice-blooded bureaucrat to think of this and then to call it an improvement for people with disabilities.”

If a user is unhappy with their FOS eligibility, they have the option to appeal—a process that requires them to submit a form from a health care professional, and be assessed by an occupational therapist.

While the option of an appeal offers a safeguard in case anything was missed in a user’s initial evaluation, several customers allege that they have fallen through the many cracks in the appeals system—or, that the system is serving its intended purpose, to shift as many users off the door-to-door service as possible.

Genevieve Blackburn, a 69-year-old who lives with a chronic pain condition called peripheral neuropathy and who cannot walk without using a walker, received conditional status when she first applied for Wheel-Trans in 2017. She says that she’s unable to ride conventional transit because of her inability to walk long distances, high pain levels, and risk of falling. Blackburn once had a serious fall that shattered her femur and forced her to undergo emergency surgery and months of inpatient hospitalization.

After filling out a form and submitting a note from her rehab specialist, who strongly believed that Blackburn deserved door-to-door access, she met with an occupational therapist at Sunnybrook Holland Centre for her functional assessment.

Blackburn informed the occupational therapist of her physical limitations and her risk of falling. The occupational therapist asked her a series of questions and then timed her walking with her walker across the room and back, which she estimates was less than 20 steps.

After Blackburn completed the test, the occupational therapist told her, “You don’t look feeble.” Blackburn attributes the comment to the invisible nature of her pain.

“It was kind of degrading. I felt very uncomfortable with her,” Blackburn says, still visibly shaken by the OT’s judgment. “I’m in chronic pain 24/7.”

At that moment, Blackburn feared she wasn’t going to get unconditional eligibility status.

A few weeks later, her fears came true—she was given conditional eligibility status with access to door-to-door during morning and evening rush hour. Blackburn says that she doesn’t know why she got the rush-hour conditions, given her ability to walk doesn’t change based on time of day.

The distance that Blackburn walked during the functional assessment was far less than the distance she’d be required to walk while transferring between Wheel-Trans vehicles, subways, buses, and streetcars. Other users interviewed for this story have similarly described only walking about 10 to 15 metres during the test.

Blackburn wants to use FOS and conventional transit: she has tried taking the bus short distances accompanied by her husband, and has even attended a TTC travel training course. But she has struggled with high pain levels and fatigue each time. The TTC employee accompanying her during travel training even spotted her discomfort, saying, “I’m noticing that you’re having a lot of difficulty.”

When she informed her doctor that she was denied door-to-door service, he was baffled. Blackburn and other users interviewed for this story feel that their health care professionals’ recommendations were not given enough weight in the eligibility status decisions.

“I just think it’s very unfair that somebody who meets you for 15 minutes can make a decision that affects your life in such a big way,” Blackburn says.

Milton says that information on the application from the health care professional is factored in when rendering eligibility decisions. But the issue of health care professionals’ notes and their role in determining Wheel-Trans eligibility has surfaced in the past. In an article published by CBC in 2012, TTC’s then CEO, Andy Byford, stated, “We wouldn’t support going with patients’ individual doctors because we found in the past that that has only led to claims and numbers of customers going higher.”

Advocates have expressed concerns about the potential conflict of interest in eligibility evaluations. Wheel-Trans staff are responsible for making eligibility decisions using an internal rubric—decisions that could be influenced by budgetary constraints and diversion targets. Milton denies the allegation.

Two users interviewed for this story also complained about the functional assessment’s ability to test for their changing abilities and needs. Both users attended the functional assessment on “good symptom” days, and argue that the test failed to account for the dynamic nature of their disability and accessibility needs.

Dynamic disabilities, in which one’s symptoms and condition fluctuate from day to day, are very common. According to the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability, over 60 percent of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over have dynamic disabilities. Urban planner and former ACAT chair Igor Samarzdic says that it’s very difficult for systems to quantify disabilities that fluctuate on a day-to-day basis, which can lead to incorrect eligibility designations.

Wheel-Trans says that questions about fluctuating disabilities are included in the initial application. These users, Milton adds, will “get the benefit of the doubt” during the evaluation process and should receive unconditional status.

Rowan, the 77-year-old woman who uses FOS to visit her mom in her retirement home, also said that the functional assessment failed to test for the biggest barriers she faces while navigating conventional transit—standing time and access to bathrooms. She says she cannot wait at transfer points without seating and nearby bathrooms, saying, “Every second counts when you’re a senior.”

Users who are unsatisfied with their eligibility decisions can appeal the occupational therapists’ decision and meet with a three-person panel, which includes a TTC Transit Expert, a person with a disability who uses conventional transit, and another occupational therapist.

But Blackburn says that she didn’t have the energy or bandwidth to appeal the occupational therapist’s decision, and wouldn’t have trusted the appeal panel to conduct a fair reevaluation anyway. She’s not alone: most conditional users interviewed for this story said their lack of faith in Wheel-Trans’ appeal process also deterred them from appealing. Many said they knew other riders with the same disability who had their appeals denied, and believed they’d receive the same result.

“It’s very unfair that somebody who meets you for 15 minutes can make a decision that affects your life in such a big way.”

The biggest barrier to improving accessibility at the TTC, according to several former ACAT members, is the lack of people with disabilities in positions of power. While ACAT provides advice to the TTC board, the board decides whether or not their advice is actioned upon. Samarzdic, former ACAT chair, says that to improve accessibility, the TTC needs to hire people with disabilities in key decision-making roles.

“The engineers who design our subway systems, the urban planners, the architects, the professionals, and staff who oversee all these projects just don’t have a grounded enough relationship or connection to accessibility,” he says. “They are not able to fully appreciate or understand what it’s like to be a disabled person navigating the city.”

In the TTC’s five-year diversity and human rights plan, less than two percent of senior, middle, and other managers identified as people with disabilities. There are no specific plans or targets referencing disability representation in management roles.

The TTC has made some improvements in accessibility in recent years, budgeting $800 million for accessibility improvements over the next 10 years, including replacing and repairing existing elevators and escalators, improving wayfinding at subway stations, installing new accessible bus and streetcar stops, and purchasing new Wheel-Trans buses.

But until the conventional transit system and the FOS system see significant improvements in accessibility and reliability, FOS risks pushing people who are already marginalized even further into the margins. Users rely on accessible transportation for everything—work, social outings, recreation, shopping, and doctor’s appointments. When they are forced to use FOS, they will suffer losses in safety, autonomy, and physical, mental, and financial well-being.

Prior to the pandemic, Blackburn used Wheel-Trans door-to-door service three times a week to attend exercise classes, which have helped her improve her strength and mobility while making close friends. Wheel-Trans also helped her regain a sense of independence—she didn’t have to rely on her husband to drive her everywhere. When FOS becomes mandatory for her, she will be forced to depend on her husband whenever she leaves the house and won’t be able to attend exercise classes whenever he’s busy.

Blackburn recognizes that her situation isn’t nearly as bad as others. “With me, I have options,” she says. “I have him to drive me around…but there’s people who don’t have that option.”

Kristina Hedley applied for Wheel-Trans after severely injuring her ankle and received conditional status. She takes Wheel-Trans to doctor’s appointments and to go shopping. On her good days, she can use a walker. On her bad days, she needs her electric scooter.

She lives alone at the corner of Weston and Lawrence, far from any subway station, so taking conventional transit means riding the bus. On the few occasions that Hedley has brought her scooter on the bus, she has required help from two strangers to turn her 350-pound scooter around so that she can safely strap herself in. In the past, this has delayed the bus and angered riders.

Hedley has appealed her conditional status three times, and has been denied door-to-door every time. She plans on appealing again.

“Wheel-Trans should be a staple,” Hedley says. “It should be there for anyone who’s disabled to use, whenever they need it.”

Hedley doesn’t have family or friends living nearby who can drive her around. When FOS becomes mandatory for her, she won’t leave her house as much anymore. If anything’s close enough, she’ll take her scooter, but she refuses to take conventional transit.

“TTC doesn’t care about the disabled anymore,” Hedley says. “I’d like for [FOS] to not exist at all.”

Correction: A previous version of this article inaccurately stated that the TTC planned to remove redundant elevators from subway stations.