I ’m at the age where people ask me if I’m going to have kids. It comes up on phone calls with family. Friends discuss it between sets at the gym. On dates, the question is thrown around casually. Could you see yourself bringing life into this world peppered in between inquiries about what podcasts I listen to and whether or not I’ve seen The Wire. For a long time, my main thoughts on fatherhood were that of deferment. It’s something I’d think about when I was older, like prostate exams or caring about the thermostat. But approaching my mid-30s, the topic is harder to put off. The main issue I keep coming back to is whether having a kid means letting go of a career and lifestyle I’ve chased nearly every moment for the past 15 years.

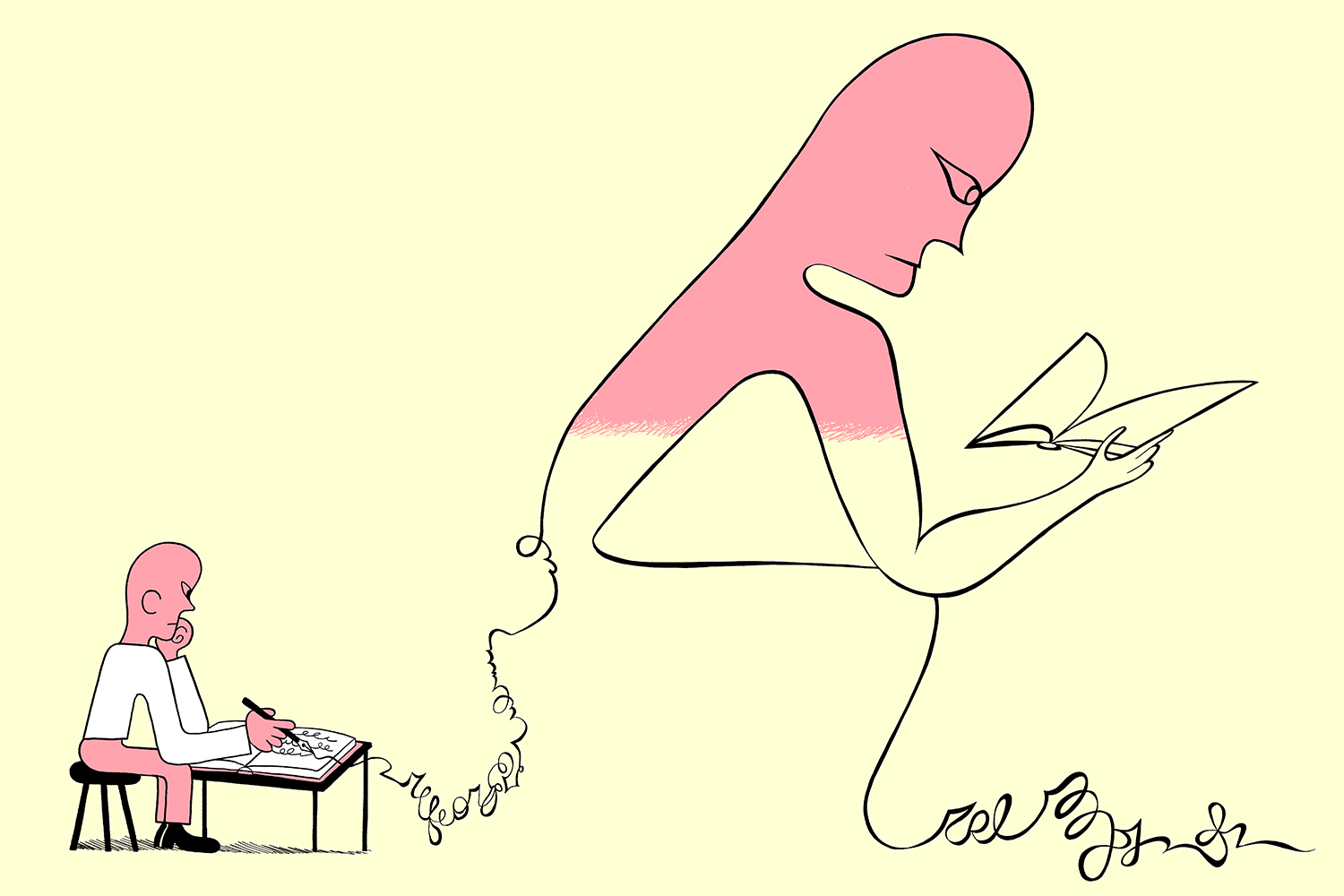

I am a working artist in Toronto. When I say that aloud, it conjures romantic images of wistfully scribbling in front of some giant loft window. Questionable fashion decisions. A turtleneck or double knee denim. Practically, it means that I make my living through a mishmash of creative projects. Writing plays and the occasional acting gig. Punching up television scripts. Narrative journalism and amateur photography. Jumping from gig to gig, I’m able to afford a rent-controlled apartment and groceries. Once a week, I buy a beer or two or go out for dinner.

Getting to work in the arts is something I’m extremely grateful for. But the tradeoff for a career I like—something that I’m ostensibly successful at—is the constant need to find new ways to sing for my supper. If I’m not creating, I’m not getting paid, and in Canada’s largest city, it’s never an option not to get paid for too long. According to real estate analysis company Urbanation, the average two-bedroom apartment rents for over $3,300. The average house price comes in at over a million dollars, not to mention the increasing cost of food. When deciding to have kids, affordability and stability are major factors. Not knowing where your next cheque is coming from is fine when you’re only responsible for yourself—less so when there is a tiny mouth to feed. For a lot of people in the city, choosing a career in the arts or choosing to have a family is an either-or scenario.

Art + Money

Subscribe to our free newsletter to get our stories delivered directly to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

For producer Andrea Donaldson, artistic director at Nightwood Theatre, the discussion about motherhood and affordability felt like one of the most pivotal conversations happening among her peers. It’s an undercurrent in the recent play Universal Childcare, created by Quote UnQuote Collective in association with Nightwood Theatre, which ended a critically acclaimed run in February with a “babe in arms” performance that encouraged audience members to bring along their little ones.

“I never thought having a baby as an artist would be possible,” Donaldson wrote in a blog post about the show. “And artist or not, many new parents—especially women—have to exit their workforce just as they are hitting their stride in their careers.”

“Others basically pay to go to work (like I did) simply to remain viable and maintain professional practice…[the creators of the show] knew that childcare was a hugely urgent feminist issue for all, whether you are—or intend to be—a parent or not.”

The national child care program, operational countrywide by 2026, promises some respite from the challenges of parenthood, but factors like waitlists for available daycares, their physical locations, and drop-off/pick-up times are still contributing factors. For actress Mina James, childcare played a huge role in shaping her career choices.

“I was offered a contract that I couldn’t take because it was out of province and there was no childcare provided,” said James. “And it was the realization that it would cost me thousands of dollars to perform, because I would have to find childcare and pay for it privately on my own. There was no support from the company. On top of that, I wouldn’t make much money on the gig itself.”

The day-to-day realities of being a mother, combined with the economic realities of working in the arts, meant that James had to take a step back from performing on a full-time basis.

“I don’t really know how the artistic community at large can grapple with goals like diversity, inclusion, and equity. If there is the stress of being a potential breadwinner in your family, going into the arts isn’t open to you.”

There will always be those who make it work, but the idea of making a middle-class living as a Toronto creative feels like a thing of the past.

There are plenty of artists across the city who have children—who figure out ways to make it work. But like a lot of finance discussions in Toronto, exactly how these folks make it work is shrouded in secrecy. Is it a supportive partner? A trust fund? Crime? Sorcery? There are those who bought homes when it was still affordable to buy homes in this city. There are lucky people locked into rent-controlled apartments. There’s the fact that a lot of the time, it is easier for a man to be an artist and a parent than a woman, thanks to gendered expectations around motherhood. Because no one is ever encouraged to talk about these things—lest they seem privileged or braggadocious—it’s hard to know what’s really going on.

Stage performer and clown Adam Lazarus, who is a father of two, notes that everything takes a ton of planning. Every time he books a gig, there is the balancing act of supporting his family and supporting his creative work.

“My wife and I have this thing where we try and say ‘yes’ until we have to say ‘no’,” said Lazarus. “I wanted to be able to perform my shows, but if I was going to do that, my family needed to be able to come. It got built into my rider that if I was touring, they were coming with me because they’re priority number one.”

Lazarus notes that his situation wouldn’t be possible if his wife didn’t also work for herself. Prioritizing family has also made him consider the kind of work he takes on: long runs of nightly shows or big television jobs might not be possible with their scheduling. And while Lazarus spends 80 percent of his time making art, the majority of his income comes from communications consulting. It’s work that feels adjacent to his creative jobs without being the exact thing he loves to do with his life. It’s one of the necessary compromises almost all working artists make, though something we rarely talk about when discussing the success of those artists.

“I think it’s a fallacy that things don’t work. That there’s a certain way that this whole life works,” Lazarus said. “It’s easier in partnership, when you’re able to support each other. But if you want a family and you want to create, there are ways to work things out, it just might not always look like the idea you had in your head.”

The main issue I keep coming back to is whether having a kid means letting go of a career and lifestyle I’ve chased nearly every moment for the past 15 years.

When I talk about the challenges of being a parent and an artist, friends and family members have varying degrees of sympathy. A lot of the feedback I’m faced with boils down to the idea that working in the arts is inherently a younger person’s game. I’m not allowed to lament some of the tenets of adulthood that remain inaccessible to me—kids in this case, a healthy savings account as another—while still gallivanting around writing scripts and making up stories. Those kinds of arguments cut close to the bone. It’s the insinuation that art and creative work are somehow less than. Not a real job at all. And while it’s true no one is owed an artistic living, the notion that anyone making a living creatively isn’t doing real work can be frustrating. It takes a staggering amount of drive and commitment to make things work.

There will always be those who make it work, but the idea of making a middle-class living as a Toronto creative feels like a thing of the past. It shouldn’t be a pipe dream to have a kid and perform, create, and thrive in this city. But with venues closing down and artists leaving, more and more that feels like the case.

If artists are forced to choose between being supported by outside means—family money, a rich spouse—or spending their lives perpetually struggling to afford the basics of human existence, who will get to make art? If a working artist has to make choices between creating and having a family, what kind of stories will we miss out on?

On a personal level, I’ve been grateful to thrive creatively in a place like Toronto. It’s just the success doesn’t feel like it’s amounted to much on a material level. The cultural cachet of seeing your name in the newspaper or on a TV screen feels great, but that’s not something you can build a foundation on. And if I’m going to have a family, I want a foundation. So…will I ever be a dad? Jury’s still out. What I do know is that if I decide to go that route, I want to raise my kid with the idea that art has value and importance on a broader societal level. With the way things have been going, I’m afraid it may be hard to convince them that’s true.

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Foundation. All stories were produced independently by The Local.