On a mid-December evening, the entrance to the community centre gymnasium is crowded with people waiting patiently to enter the holiday party organized by the Lawrence Heights Revitalization office. Inside, rows of tables have been set up classroom style, decorated with tablecloths and a snow globe. A DJ spins seasonal songs at one end of the room while a row of volunteers work the food stations at the other, handing out cups of ruby red Caribbean sorrel.

With his neighbours celebrating around him, Paul Letherby doesn’t want to spoil the festive spirit by talking about revitalization. Wiry and bespectacled, his age hanging on him loosely like his thick bomber jacket, Letherby is an active and vocal member of the Lawrence Heights Inter-Organization Network (LHION). “I really don’t want to talk about the revite because once I start, I won’t stop,” says Letherby, using the shortened moniker locals use when talking about the project that is transforming their community. He shrugs as he speaks. “People are having fun.”

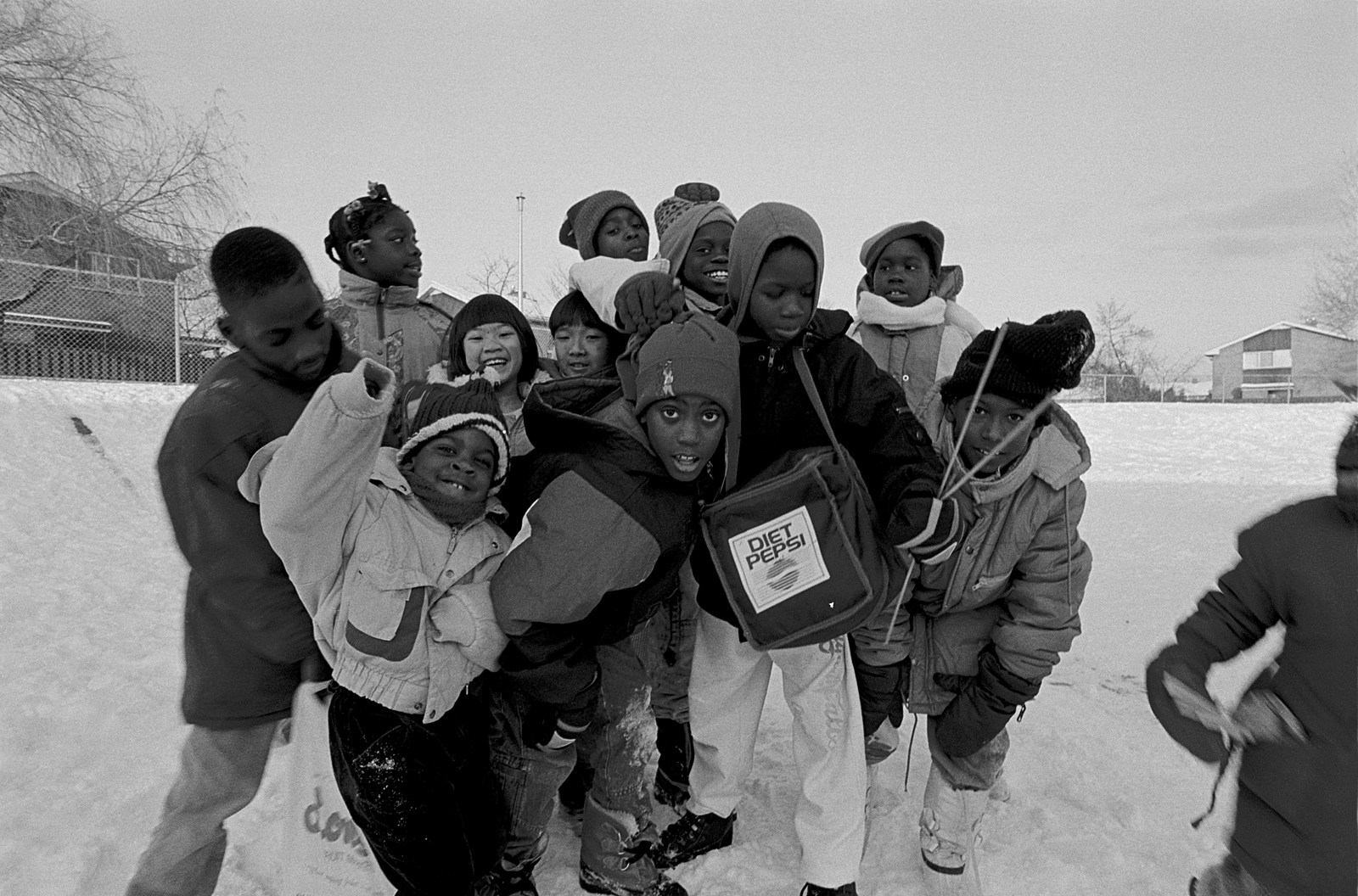

Letherby and his neighbours are living through an ambitious, twenty-year project that promises to fundamentally change the place they live. Lawrence Heights is Toronto Community Housing’s largest revitalization project yet, almost double the size of their previous project in Regent Park. The project is meant to address common complaints made by residents about old housing units badly in need of an overhaul, and the lack of opportunities felt by a racialized, working-poor community fenced in between two prosperous neighbourhoods. Locals talk about feeling isolated and ghettoized and the media’s long-standing portrayal of the neighbourhood—often referred to as “Jungle”—as being ridden with crime and gun violence.

Along with replacing 1,208 Toronto Community Housing (TCH) units, the project will build more than 4,000 private market units, as well as new parks, retail space, and roads connecting Lawrence Heights to surrounding communities. Residents like Letherby can now see the concrete structures of the project’s first phase. And while there’s a feeling of excitement about the physical and social changes taking place, a large part of the community feels frustrated about the time it’s taken to get shovels in the ground, even as they continue to deal with the crumbling infrastructure around them.

“There are lots of people here who can tell you about the maintenance migraines we’ve all been dealing with: flooding, heat’s not working, just things breaking down,” says Letherby. “Repairs haven’t been happening. They just patch up these buildings that are way beyond their lifespan. The whole thing is just… too… long,” he says, drawing out the last sentence to emphasize his exasperation.

For some, those frustrations are compounded by a feeling of anxiety due to a lack of communication. Residents are apprehensive about their future in the community, now a large construction zone, with fenced off sections dotted with bulldozers, torn-down townhouses, and mounds of earth.

The New Lawrence Heights, as the developers refer to the project, is one of the city’s biggest social-engineering schemes, seeking to reinvent a neighbourhood notorious for poverty and gun violence into a desirable, family-friendly location with access to many acres of green spaces, prestigious clubs and schools, and easy access to public transit and highways. It aspires to orchestrate a mixed-income society, where a new luxury lifestyle will co-exist side-by-side with social housing. At the end of it, the planners say, you won’t be able to tell the difference between the two types of residents. But meeting the needs of long-term residents while appealing to affluent newcomers is a difficult balance to strike.

“I really don’t want to talk about the revite because once I start, I won’t stop.”

Sandwiched between the Yorkdale Mall to the north, Lawrence Avenue to the south, and Dufferin and Bathurst to the east and west, Lawrence Heights was built in the 1950s as the first large scale public housing project located outside of the former City of Toronto boundaries.

When it was first proposed, there was suburban opposition to the project. The multiple dwellings were viewed as “blots upon a suburban landscape where, until 1960, few residential structures had stood, except for single-family, one- and two-story dwellings,” writes Albert Rose in Governing Metropolitan Toronto.

Its proximity to Downsview Airport ruled out high-rise buildings. Instead, row houses, low-rise apartment buildings with no more than thirty units each, and detached homes were built along a network of cul-de-sacs that isolated the community by design. The rent-geared-to-income housing units were built primarily for families, and also included units for senior citizens.

The purposeful architecture that disconnects Lawrence Heights from the surrounding, more affluent, neighbourhoods is one of the reasons locals like Kaydeen Bankasingh believe their home is called “Jungle.”

“I’ve heard that there were so many trees and when everything’s in full bloom it was beautifully green everywhere,” she says, sitting down in the food court of the newly rebuilt local mall, Lawrence Allen Centre (previously called Lawrence Square). “I also heard that taxi cabs—because there’s this one circular street, and little enclaves and little courts off of it—found it difficult to navigate and drive. So it’s like you’re driving with all these trees, and you can’t find your way out. You’re in the jungle.”

That shorthand quickly took on negative overtones, however, and media reports began to associate the “Jungle” with drugs, poverty, and gun violence as early as the 1970’s. That spectre still haunts the neighbourhood, especially given several cases of gun violence in 2019.

Bankasingh moved into the nearby Neptune neighbourhood 12 years ago, and has been watching the revitalization project from its launch in 2008. Then a recent York University graduate and mother to a seven-year-old daughter, she had been couch surfing for several years before she found out about TCH’s program for the homeless, eventually landing a unit.

After settling into her new neighbourhood, Bankasingh started to attend early revitalization consultations in June 2008. Given the backlash that the agency had faced with their Regent Park revitalization project, especially around relocating residents from that community, TCH staff were keen on taking in as much feedback from Lawrence Heights residents as possible.

“There were a lot of barbecues,” laughs Bankasingh. The initial conversations ranged from explaining what revitalization meant, to assigning a group of community animators to serve as liaisons between residents and Toronto Community Housing. Bankasingh was one of the original community animators and even worked for TCH for four years before leaving her position there. It got confusing to keep her personal and professional lives compartmentalized, she says.

At first, it seemed like the agency was truly listening to the residents. A clause that said no current residents would be displaced, as well as the promise of training and employment opportunities for residents to work on the construction site, were seen as significant wins by the community. A Social Development Plan was created to try to ensure that social and economic improvement took place alongside the physical redevelopment of the housing stock. The Heritage Plan reflected the community’s desire to memorialize the tangible and intangible histories of people who lived there. There were also conversations about residents being able to potentially buy a home, with rent-to-own schemes.

Over the years, however, as staff changed, some of the initiatives that had come out of the older community consultations, such as the Heritage and Social Development Plans, seemed to fall by the wayside, only kept alive by concerted advocacy efforts from the community. The future of the new community centre, promised as part of phase two of the revitalization project, is now in question, with building stalled after the provincial government withheld funding. Even acknowledging the community’s history as “Jungle” isn’t part of the current project, says Bankasingh. “Right now Toronto Community Housing refuses to create any association with this new community they are building to ‘Jungle’ because the media has framed this reference as this place that’s violent, that’s gang-ridden,” she says, the frustration in her voice building. “They refuse to honour the name, reference it, or create any connection to it … [They] decide they don’t want to reference it because it’s going to dissuade buyers.”

Remembering the community’s history is also important to Elena Korniakova. An architect by training, she’s one of four co-founders of the Lawrence Heights Arts Collective, which gathers regularly at one of the vacant units slated for demolition to present their latest artworks or for impromptu jazz jams.

“Come, come, come,” says Yuri Malaev one afternoon this winter, setting aside his rake and gesturing at passersby, breaking into short bursts of Russian as he guides them towards the entrance. Inside, a handful of collective and community members are looking at some of the recent art additions to the space while Denys Mutaganda, a recent immigrant from Congo, shows off his intricate banana leaf artwork.

Although Korniakova has been living in Lawrence Heights for two decades, it wasn’t until she co-founded the arts collective five years ago that she truly got involved in the community and started to learn more about the revitalization project. The collective came about after she happened to meet Malaev, a fellow Russian immigrant and a sculptor, as she was walking around the neighbourhood.

“For us, the revitalization project is good because we got space to create and display our artwork,” says Korniakoa, speaking with a Russian lilt and gesturing around their unit on Varna Drive, which has been transformed into a miniature art gallery and studio. This is their second location, after the first unit they were allocated was demolished. Some members of the collective helped renovate the main floor and basement of their makeshift gallery, building furniture and display cases, though they’ll likely have to move again in a few years.

While she supports the revitalization, Korniakova hopes the project is able to preserve neighbourhood landmarks like Bredon Hill, located behind Flemington Public School. It’s a popular gathering spot, especially for tobogganing in the winter, but the current plan is to flatten it to accommodate the new development. “People who have lived here remember this hill as one of the best places,” says Korniakova. “It’s a focal point of the neighbourhood.”

That unsettling feeling, of watching the landmarks and physical markers of a community being removed before your eyes, is a common one in Lawrence Heights these days. Right now the revitalization project is in its first phase. The first of two “Yorkdale” condos stands next to a mid-rise TCH building south of Yorkdale mall. Meanwhile, adjacent courts along Varna Drive have been demolished. Large patches of land have been fenced off, pathways blocked, the roads dotted with signs announcing temporary changes to the bus route.

Watching the physical geography around her change is part of what motivated local artist Ashna Parbatie, 22, to get more involved with her community. “We had a lot of questions about what will happen to the future of the community. I wanted to clarify what revitalization would do for us,” she says.

Parbatie started volunteering with TCH, making flyers and doing community outreach. “The more I participated, the more I learned about the revite,” says Parbatie. She’s cautiously optimistic about what’s promised—more greenery, more gardens, new scholarships, and the promise to move people within the community rather than replace them. But she thinks there could be better communication between the revitalization staff and the community. The updates should be done at community events on multiple dates and multiple times, given the varying schedules of people’s lives. “I know there are a lot of rumours, which people tend to think are true,” she adds.

Other youth in the community are concerned about their safety, says Raamla Adan, 31, who has a postgraduate degree in addiction and mental health from Humber College. “These street lights don’t work at night. The walking routes have changed. Young people are scared of going out, especially with the recent violence in the community,” says Adan, referring to the series of shootings in the summer and fall of 2019. To combat the rising issues of mental health among the youth in Lawrence Heights, Adan founded a grassroots initiative called Hope and Hustle Heights a year and a half ago. The group organizes art events such as open mic nights to help youth address their concerns.

“There is resilience in the community,” she says. “But why isn’t revitalization addressing simple concerns, like fixing the street lights? It doesn’t make sense.”

For Kaydeen Bankasingh, the neighbourhood’s changing landscape means certain parts of the community will be lost. Walking around the Lawrence Allen Centre, she points out the few remaining mom-and-pop stores. It’s one of the many signs of rapid gentrification she sees in a neighbourhood that’s known for its tight-knit community.

“Many of us are wondering how long this rug shop, for example, is going to last. Probably not much longer because it’s become so expensive to be here in the mall,” she says. It may have been dingier in the past, but there was a sense of the space being a local hub. Besides relevant retail stores, the mall offered easy access to services, “whether it’s Pathways to Education or even my agency, North York Community House. They had space on the fourth floor as well.”

The eventual demolition of Northacres Apartments also runs the risk of destroying the tight knit community of elderly residents. “They check in on each other, you know,” she says. “They know each other’s medical appointments, and other schedules. I don’t know what will happen when they have to move out. Will they be able access that community network again? I don’t know.”

On a blustery January afternoon, a saleswoman shows passersby the swank sales centre for the New Lawrence Heights development. The model unit offers a glimpse of the luxury living for sale—a modern bathroom featuring his and hers vanities, gleaming white sinks atop dark wooden cabinets, a sleek white freestanding bathtub, all illuminated by soft chandelier light.

Visitors are supposed to make an appointment, but it’s a slow day and no one is shopping around for a place to live. They are now selling the second phase of the townhomes, called Bedford Park, with units priced at around $900,000. The first phase of townhomes were priced at a million and sold out within a weekend. Occupancy is expected sometime in 2021.

These buildings are being built in close proximity to affordable housing units in a bid to create a mixed-income community. The actual results, however, have left some TCH residents with mixed feelings. They are looking forward to moving into their new buildings as they come up. However, there’s also some criticism in the clear way that the affordable units can be differentiated from the market rate dwellings.

Take, for example, the 14-storey condo tower facing the seven-storey TCH building, separated only by a common walkway. “The idea is that you can literally look into each other’s balconies in the summer, I guess,” says Bankasingh. While the exteriors of both buildings look very similar, it’s immediately clear which building is which.

In a way, the community continues to be segregated, says Parbatie.

“I don’t get why they have to be separated like that,” she says, adding that she’s never met any of the residents who live in the condo. “I am not really sure who lives there.”