On a muggy Wednesday evening in mid-July, Chiara Padovani and campaign volunteers were canvassing on the 19th floor of a highrise near Jane Street and Emmett Avenue.

“Knocking on my neighbours’ doors is my favourite thing to do,” says Padovani, the 34-year-old social worker and community organizer who hopes to become the next councillor for Ward 5 — York South-Weston.

When she was 16, it was a door knock from a local candidate for member of parliament, Paul Ferreira, that got Padovani excited about politics. “Even though I wasn’t eligible to vote, he was interested in what I had to say and what my priorities were,” she recalls.

From Padovani’s slow, methodical pace, it’s clear that the experience stuck with her. A full hour into canvassing, she had barely completed two floors, preferring instead to spend the 10 or 15 minutes needed to build quality connections with each resident—the pet owner concerned about the state of the dog park up the street, the college student taking an interest in civic matters like Padovani did when she was 16.

Building up a base of supporters to take on an incumbent with decades of accumulated name recognition is slow, grinding work, but it’s work that’s familiar to Padovani. Back in 2018, when she first ran for a seat on council, she was up against two heavyweight incumbents with a combined 63 years in municipal office. Padovani had zero (she still does). Despite the long odds, she came in a close third, with 20 percent of the votes.

This time around, the odds look more favourable, relatively speaking. Padovani is up against just one incumbent, Frances Nunziata. The trouble is, Nunziata hasn’t lost an election since taking office in 1988, the year Padovani was born.

“I have absolutely nothing personal against the incumbent in York South-Weston. In fact, as a young woman who’s in politics now, I have immense respect for the women who were doing this work 30, 40 years ago before me,” says Padovani. “But the way we did things 30 to 40 years ago isn’t working and it’s really time for bolder leadership.”

Padovani is not alone in thinking this way. Across much of Toronto this fall, challengers like Padovani are quietly pounding the pavement in the hopes of unseating councillors many years their senior. Unfortunately, it’s a fight they’ll lose 9 times out of 10—not because they are unqualified or not knocking on enough doors, but because the system is set up to give incumbents an outsized advantage.

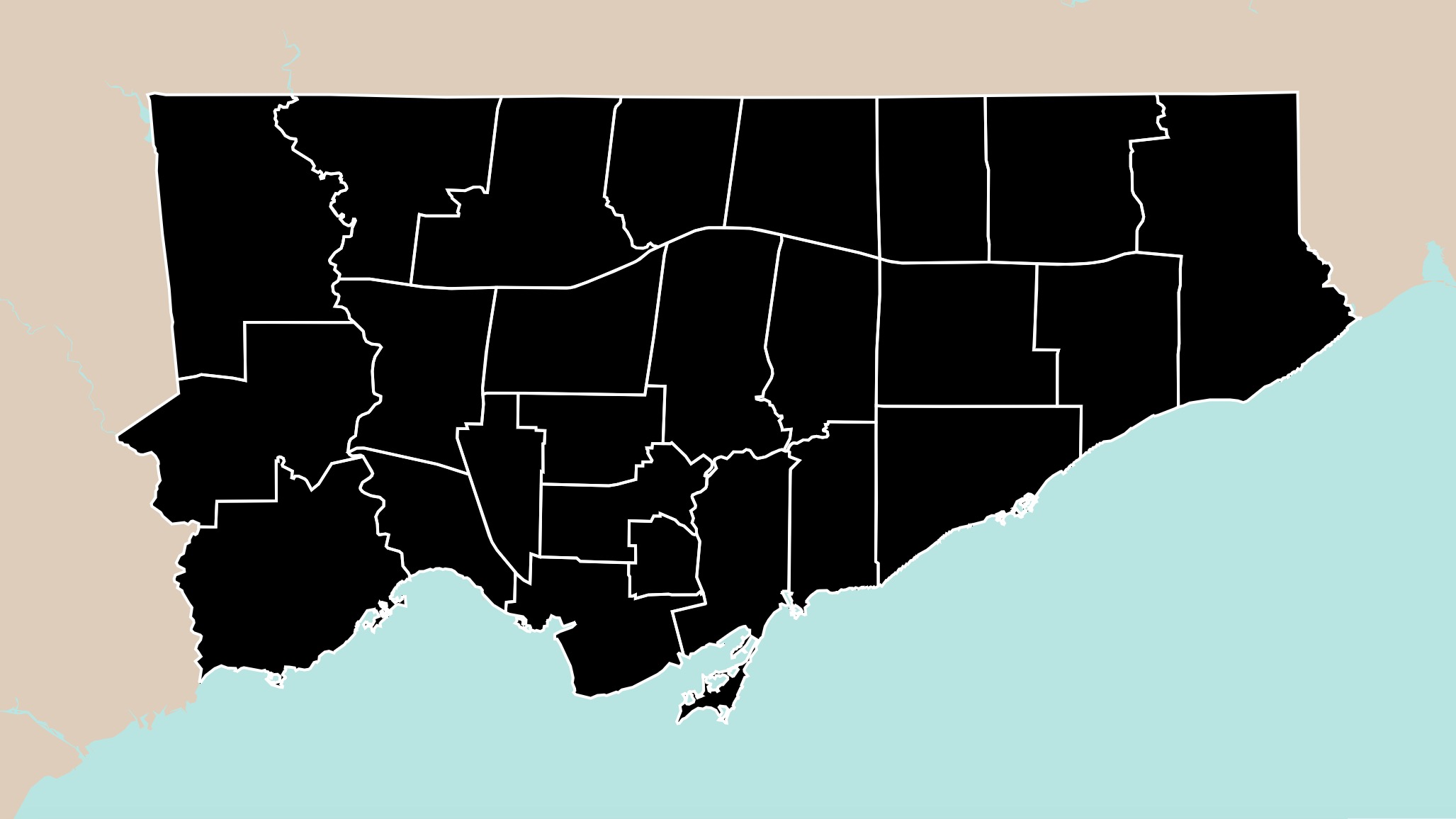

The incumbency advantage is a problem in most cities, but in Toronto it’s uniquely potent. The Local’s analysis of the ten biggest cities in Canada and the United States found that the average Toronto council member has been in office for 13.8 years—longer than any other city by a sizable margin. It’s an advantage that has helped to insulate the predominantly white city council from the rapidly changing demographics of Toronto, and has gradually lessened the significance of municipal elections as competitive contests of city democracy.

Get Election Ready with Candidate Tracker

A lot can change between now and election day on October 24th. Bookmark Candidate Tracker to stay up-to-date with fact-checked bios and issue-driven analyses.

When incumbents in Toronto seek re-election, they’re virtually unbeatable. Their success rate is now well above 90 percent, higher than at any point in the city’s history. This excludes the anomalous 2018 election, in which several incumbents lost only because they were forced to run against other incumbents after the Ford government merged a number of wards in Toronto.

Jack Lucas is a University of Calgary political scientist who studies municipal incumbency. According to him, some of an incumbent’s success can be attributed to the personal qualities of the candidate. “If a boxer wins and then goes on winning, we’re not really shocked because we know that that boxer is good at what they do,” says Lucas. But according to his research, those qualities play only a minor role: well over half of overall incumbency success is due to the simple fact that they’ve held office—an advantage unavailable to challengers.

Being the incumbent gives you the opportunity to build a reputation and relationship with your constituents because you get to be the one who goes to the ribbon cuttings or community events, who sends out glossy newsletters or solves the parking problems on their street. It’s an edge that grows with each successive term in office. And barring any fiery scandal, you can virtually cruise to victory with that advantage alone. But that’s not all: incumbents also benefit from what’s called the “scare-off effect,” in which high-quality challengers are dissuaded from running. “So there can be a kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy where people know incumbents do well, so they don’t run against incumbents, so incumbents don’t face really serious challengers, which means they do even better,” says Lucas.

Indeed, in the seven wards where incumbents are not seeking re-election this fall, there are an average of 10.6 candidates running. In the 18 wards with incumbents, there are just 4.9.

According to Lucas, no city does incumbency better than Toronto. “It’s so baked into Toronto city politics that people sometimes forget that it’s even there,” he says. “But when you take a step back and you look at Toronto in comparative perspective, it really is one of the distinctive things about the city.”

The Local’s analysis of the makeup of city councils across the 10 biggest cities in Canada and the United States reveals the scale of the problem. The analysis shows that an average Toronto council member has been in office for 13.8 years, far longer than anywhere else.

Some of the differences can be explained by the idiosyncrasies of political systems in the various jurisdictions. For example, New York City has term limits, preventing council members from being elected for more than three consecutive terms. Unlike Toronto’s non-partisan elections, Montreal and Vancouver have political parties, which lend resources and credibility to candidates and help to level the playing field. Toronto has none of those things.

Toronto’s incumbency problem has implications for the representativeness of city council. The Local’s analysis of the ethno-racial makeup of city councils in the 10 biggest Canadian and US cities yields some stark findings: big American cities have far more diverse city councils, with large numbers of Black and Latinx members that match or even over-represent the demographics of their population. For example, in both Chicago and New York City, where the majority of the residents are no longer white, roughly two out of every three council members are non-white.

In contrast, Canadian cities have largely white city councils. In Toronto, where 51 percent of the residents are visible minorities (they’re actually the majority), only four of the 26 council members are non-white.

If challengers are only winning 10 percent of elections where they go head-to-head with an incumbent, Lucas says, it can take a very long time for city council to have sufficient turnover for new faces to prevail. “For people who are interested in the diversity of Canadian municipal councils, women’s representation on Canadian municipal councils, or new ideas, new voices, fresh visions on municipal councils, incumbent success rate prevents or slows down that transformation,” says Lucas.

Of course, there are advantages to re-electing the same councillors who’ve been there for decades, who have long-standing relationships in their wards, who understand the ins-and-outs of city hall and can stick-handle a local priority through municipal bureaucracies. But all of that comes at a cost.

Amber Morley has lived in Ward 3 — Etobicoke-Lakeshore her whole life. As a 33-year-old Black woman raised by a single mother, Morley learned how to advocate for herself and her community from a young age. Since 2004, she’s been organizing basketball tournaments, speak outs, and all-candidates debates. She’s been on local community police liaison committees and has been an assistant to two city councillors. In short, she has always believed in public service and in our system of democracy. But lately, she’s been frustrated by the widening disconnect between citizens and their political representatives.

“We say all these nice, great things about ‘diversity, our strength’ and representation and inclusion and all of these buzzwords, but ultimately it’s very performative,” says Morley. “Our council does not reflect our city, and I think it’s also part of the reason why residents don’t feel respected or reflected.”

Morley is running for the second time against incumbent Mark Grimes, who has been Etobicoke-Lakeshore’s councillor since 2003. In 2018, Morley came second, with 27 percent of the votes compared to Grimes’ 41 percent. Morley believes her numbers would have been a lot higher if not for Mayor John Tory’s robocalls endorsing Grimes, who had been under fire for improper dealings with two condo developers and for his poor attendance record at city council meetings. So when registration opened in early May, Morley was among the first to file her candidacy, eager to pick up where she’d left off. Grimes, on the other hand, didn’t register until the final week of eligibility in August, more than three months later.

Giving your opponents that much of a head start makes little sense in any competitive contest, and says a lot about the invincibility some incumbents feel in the upcoming election. But Morley isn’t bothered. “For me, it’s an opportunity to get out early and have a strong start,” she says.

What really bothers her are all the intricate ways the incumbency advantage plays out on the campaign trail, adding obstacles to an already uphill climb. For example, sitting councillors are given an annual constituency budget which they can spend on a range of eligible expenses, from newsletters to flyers to community barbeques. In an election year, the rules forbid councillors from using the budget for such purposes after August 1, which Morley thinks is too deep into the election period.

“In May, June, July, they can be out bringing ice cream trucks to the park or whatever, trying to gain favour with residents using their budget, which I don’t have access to as a grassroots organizer,” she says. And while an incumbent is able to put out a ward-wide newsletter via Canada Post on the city’s dime as long as it’s not explicitly about their election campaign, challengers like Morley must raise funds before the first piece of literature can even be printed, let alone delivered. “It’s me and volunteers who are out hand-dropping the pieces of lit because it’s cost restrictive to send it out by mass mail,” she says.

And then there are the personal sacrifices. To be a serious challenger, candidates like Morley must make campaigning their full-time job. That means taking an unpaid leave of absence from work. For Morley, a health promoter at LAMP Community Health Centre, that means no steady income from June through November. “Everyone’s situation is different,” she says. “For me, I am living off my savings at the moment and I do about five hours of paid work each week to help keep me afloat.”

Personal finances are also strained for Chiara Padovani, the candidate from York-South Weston, who hasn’t had an income since taking a leave from her job at North York Harvest Food Bank in March. “It’s a significant financial barrier for non-incumbents to run,” says Podovani. “My husband and I have to plan financially for every election year.”

So how do you defeat the undefeated when the odds are so stacked against you? The simple answer is that you don’t. The recent history of Canadian municipal elections tells us that significant changes to city councils happen not through elections, but retirement. The reason why the average Calgary city council member has been in office for just 3.5 years—more than a decade shorter than in Toronto—is that a large number of incumbents did not seek re-election in 2021. They made those individual choices for a variety of reasons, which coalesced to produce a rare, transformative event. The same thing happened in Vancouver in 2018, when few incumbents sought re-election, leading to an unprecedented result: eight of the 10 council seats are now occupied by women.

In Toronto this fall, there will be no such fluke. Incumbents will be running in 18 of the 25 ward races, where it will be Toronto elections-as-usual: hungry challengers laying it all on the line, trying to do the near-impossible. Sure, in the seven Toronto wards where we have open races, some new blood will emerge out of the diverse arrays of candidates on the ballot. And in all of that excitement, Toronto might forget about its incumbency problem. However, when sitting councillors bow out, it merely punts the problem down field, to future elections where today’s new faces become tomorrow’s hardened incumbents. After all, even Nunziata and Grimes were once rookie councillors.