For the next week, anyway, Mike Layton’s day starts before breakfast.

In the morning, he has to respond to all the issues that arise in Ward 11, University-Rosedale, overnight. Noise complaints, violent incidents in the ward, COVID updates: these are all things any city councillor might find themselves tackling before they even get to have a breakfast sandwich.

By the time he gets into the office, Layton has many meetings on the books. He’ll sit with developers about upcoming building proposals, constituents about concerns in their communities, and with various other stakeholders on projects happening across the ward. In the evening, there’s little time for rest. Instead he attends public meetings—it’s not uncommon to have one scheduled seven nights a week, though he tries to lessen the load now that he has young children. “It wasn’t sustainable from an energy perspective,” he says.

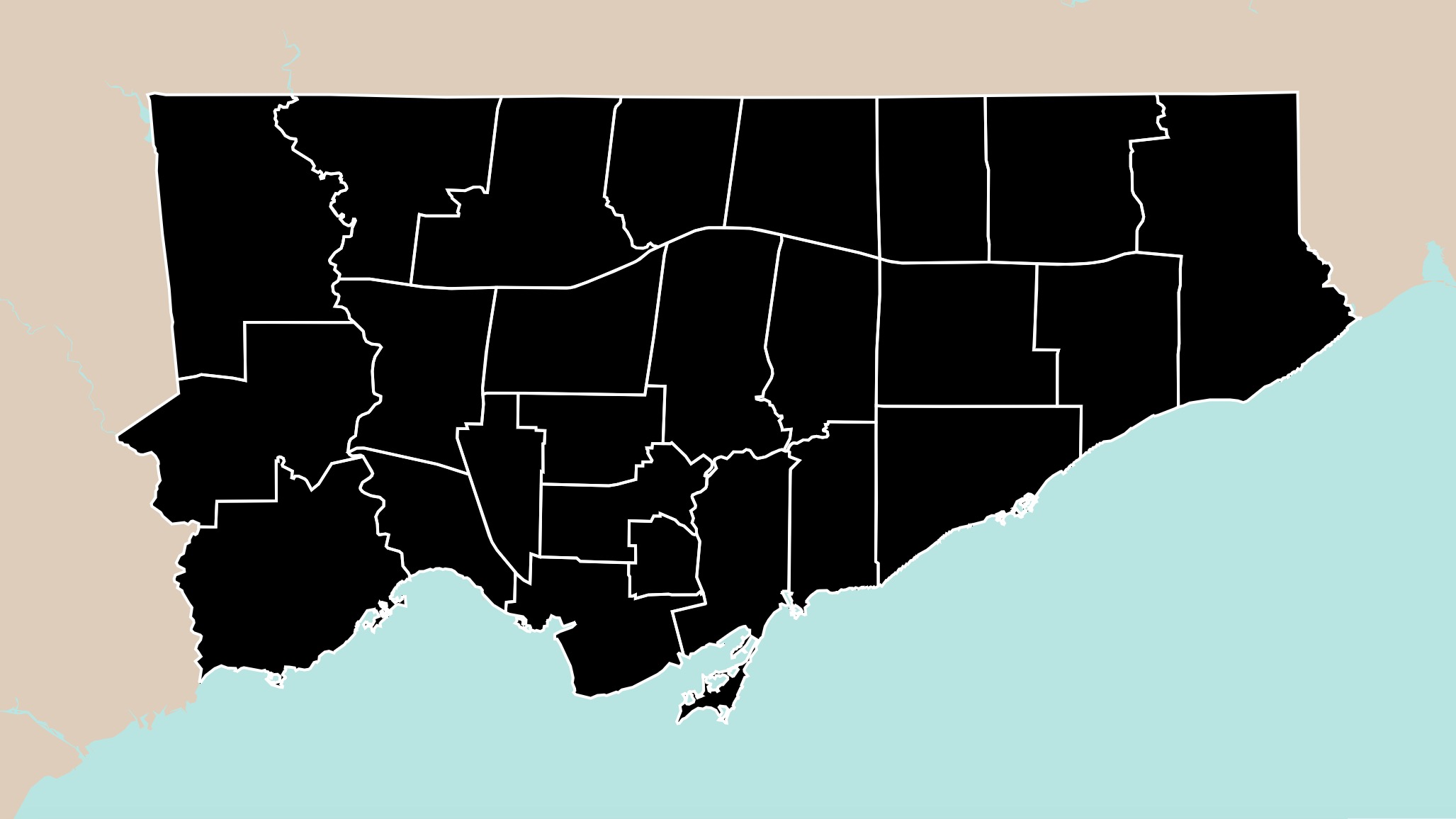

Come October 24, Layton will finally have a rest—he decided not to run again in this fall’s municipal election. But his replacement will take on a ward with over 100,000 people, and 260 currently active development applications.

The downtown Toronto wards have faced some of the biggest changes in the city over the last 20 years. As of June 2022, there were 100 high-rise buildings under construction, and over 225 cranes in the sky. At the same time, the price of a one-bedroom has risen 27 percent in the last year.

Most of the downtown wards will have brand new councillors this year. In addition to Layton, Kristyn Wong-Tam resigned their position to run for provincial legislature, and Joe Cressy left earlier this year. That means a new crop of councillors will be tasked with a rare opportunity to bring fresh vision to downtown Toronto. They will be leading the area through a period that is expected to see the population continue to explode—Greater Toronto’s population will likely increase from 6.2 million people to 8 million people by 2030, and to 10 million by 2045—all while grappling with a series of changes set down by the provincial government that may make it harder to do their jobs. It prompts the question: how can councillors lead wards as big as some Ontario towns, all while trying to develop the core in a healthy and sustainable way?

Who’s Running for the Downtown Council Seats?

Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked biographies and head-to-head analyses of all council and trustee candidates.

In the early 1970s, Toronto’s population was just over 700,000 people and Metro’s population was about 2 million. Yet, the problems were remarkably similar to those we face today: rising housing costs and gentrification of downtown neighbourhoods.

When David Crombie became mayor in 1972, he enacted a number of interventionist policies that were meant to ease the housing crisis and save cultural enclaves. St. Lawrence was redeveloped with a mix of highrise and midrise buildings, while places like Kensington Market were saved from developers’ bulldozers.

At the time, each ward in Metropolitan Toronto had just a fraction of the people they do today. It was far more likely that residents actually knew who represented them in council. But, as now, there was often resistance to change. Not everything reforming politicians and planners wanted to change came to pass. NIMBY’s had a strong voice, and they often won.

Since then, much has happened that has made city building even more challenging. Toronto’s population has exploded, while representation in council has plummeted. Meanwhile, construction is constant, but it still is not enough to keep pace with the number of people who need housing.

“I think it’s fair to say that both city staff and elected officials are to some extent overwhelmed by what’s happening and really struggling to keep pace,” says Ken Greenberg, an urban designer who has overseen projects in Toronto and around the world. He notes that while there are many projects that have had thoughtful planning around community development, in other areas, it’s the wild west.

“Look up and down the Bay street corridor,” says Greenberg. “You’re getting huge new developments just popping up everywhere. And it’s not clear that you’re getting public spaces that correspond to that.” Layton notes that the official city plan does guide a lot of the building that happens, but that city council lacks the ability to make some decisions because it is a creature of the province. (Development decisions can also be appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal, which can overrule council decisions.)

A councillor can make all the difference in ensuring a proposal comes to fruition. Take Regent Park. Pamela McConnell, who represented the area until her death in 2017, championed revitalization and increased housing in Regent’s Park. Keisha St. Louis-McBurnie, an urban planner who also co-authored Spacing’s report on the neighbourhood, notes that her leadership ensured that social development of the community was prioritized equally with real estate. “For neighbourhoods that are undergoing the revitalization process, like Regent Park, being present physically and building trust with community members is critical… and the foundation for success,” she says.

But in 2018, just as the city was set to add three wards to help better represent Torontonians, Ford slashed council to just 25 seats. Suddenly, the purview of Regent Park was in Ward 13, led by Kristyn Wong-Tam. While the new councillor did get to know the community, and advocated for affordable housing in the new developments to come, they also suddenly became responsible for a ward of over 100,000 people, including the downtown core itself—wealthy communities like Cabbagetown and the Financial District, and some of the poorest, like Regent Park and Moss Park. Their days were often 12 hours long. Wong-Tam had professional planners on staff to help with the high volume of development applications that crossed their desk.

But there’s not much they can do when Ford makes their job harder. According to the Toronto Star, in 2019, with little warning, the province amended the city’s Midtown in Focus and TOcore plans to remove language that would have ensured that housing developments would not outpace the availability of community centres, parks and, critically, sewer capacity. Height maximums for towers were almost doubled, and rules around light access and setback from the road were loosened. “Growth was never going to be our problem. We are a good place for developers to build,” says Wong-Tam. “But the challenge for us is building sustainable, complete neighbourhoods.”

That said, councillors can also stymy the development of a project, particularly if a strong NIMBY effort is underway in the neighbourhood. The number of stories can decrease, or affordable units can be cut. “There’s definitely some scepticism in that progressive wing of council… about market rate development,” says Rocky Petkov, an organizer with More Neighbours Toronto.

On the other hand, a councillor can be a powerful advocate to increase housing. Before Cressy left office, he announced that almost 60 new affordable units would be added to a development at Adelaide and John St, bringing the grand total to 254. “I think a good councillor is able to really figure out what concerns that neighbourhood might have are legitimate, and what concerns are just masks for: we don’t want anything to change about the neighbourhood we live in,” says Petkov.

In the coming years, many projects the same size, if not bigger, than Regent’s Park will begin. The transformation of Toronto’s waterfront near the mouth of the Don River will bring thousands of new residents to what was once an industrial area. The Ontario Line will bring new development to many areas of the city, including low-income neighbourhoods like Moss Park. St. Louis-McBurnie notes that this will attract new development to an area that has traditionally been one of the few downtown neighbourhoods to have affordable housing. There is also a significant concentration of social services and unhoused people who will feel the impact. “Whoever takes over Toronto Centre has a really important responsibility to think critically about what the future of Moss Park will be,” says St. Louis-McBurnie.

In the past, councillors did have one important tool to ensure the community was growing sustainably: community benefits. Before June 2022, developers who sought to build at higher heights and increased density were required to give a sum of money or build something in-kind that would provide benefit to the community. These were negotiated through the councillors office. Wong-Tam credits community benefits for supporting significant renovations to both College Park and Ramsden Park.

However, a change to section 37 of the Planning Act takes negotiation out of the equation. Community benefits are restricted to four percent of land value. City staff are now the ones responsible for determining where that money will flow, not councillors. Wong-Tam estimates that this could result in an almost 40 percent cut in community benefits flowing to communities. However, St. Louis-McBurnie says the regime is too new to understand what it means. “It’s still unclear how exactly the community can vocalize their own priorities against what may be set out in the community benefits strategy by staff,” she says.

And of course, there’s the one new law that may have the biggest impact. In September, Ontario passed “strong mayor” legislation, which gives the mayors of Ottawa and Toronto the power to veto bylaws that go against provincial priorities around housing and other matters. (Though council can veto the veto with a two-thirds majority vote. Confused yet?) Some people think that this will curb NIMBYism and allow for housing to be built quicker. Greenberg thinks, however, that this is another thing that makes councillors more powerless. In an op-ed for the Toronto Star, he also noted that much of the system depends on having a “good” mayor—what happens when it’s someone who is more beholden to developers than they are the interest of current and future Torontonians?

“I think it’s fair to say that both city staff and elected officials are to some extent overwhelmed by what’s happening and really struggling to keep pace”

While we know we do need more housing in Toronto, it is a balance between building new units and ensuring the city doesn’t lose its character. Nobody wants to live amid empty storefronts, punctuated by the odd Rexall.

When Friends of Chinatown heard a whole block of Spadina could be razed to make way for new development, the organizers lept into action. While they want more affordable housing in the neighbourhood, they also thought there had to be a way to do so while still providing space for the businesses on ground level, many that make Chinatown the cultural hub it is. So they needed to rally residents—many who don’t speak English—to make their voices heard. “There was a lot of effort [we] did to ensure language accessibility to ensure that community members knew where that consultation was happening,” says Diana Yoon, a member of Friends of Chinatown.

Yoon had planned on running for University-Rosedale councillor, the seat that will be vacated by Layton. But she dropped out of the race when she decided that her efforts would be better spent on another issue: keeping developer funds out of Toronto’s city politics. “We need councillors who will fight for the city we need, alongside people who need it most,” she said in her letter announcing she was leaving the race. “But we will need people who fight to build support and organize on the key issues facing our city to make change.” But in councillors’ offices that are already massively overburdened, the fear is that those with the deepest pockets will be able to have the most influence.

While increasing the number of wards to what was proposed in 2018 would go a long way to ensure representation, the chances of that happening during the next four-year term are basically nil—it would require a massive change of heart from Ford, who holds a majority government until 2026. It leaves the city’s elected officials in a tough spot: many now are much more limited in what they can do, when, at the same time, there is so much that needs doing.

Yoon hopes that the new class of municipal politicians will still listen to the community. “If councillors are more proactively meeting with housing organizations, more proactively meeting with renters, more proactively committed to expanding affordable and social housing, how could some of these policies change?”

So, councillors are going to have to take notes from community organizers. “They have to get loud. They can’t be passive,” says Wong-Tam. “They have to clearly articulate their vision. And they’re gonna have to mobilize the community to bring them along, because that’s going to be absolutely critical in getting the things that they want done.”