Matthew Shepherd isn’t someone who usually calls the police. As a Black, gay man, he’s wary of them. His first encounter with law enforcement was at age 15, when he was stopped on his way home from high school and questioned for allegedly resembling a suspect at large in the neighbourhood. He was only able to extricate himself when his mother spotted him from down the street and ran over to intervene.

One day this summer, however, Shepherd found himself with no other option. It was early August, and Shepherd, a 34-year-old nurse living in Parkdale, was on his daily walk when he heard someone yelling. Turning, he spotted an angry older man on a bike, perhaps in his 50s, shouting at him.

“He was just screaming out a bunch of homophobic slurs,” says Shepherd.

Shepherd isn’t used to being harassed—he’s six feet tall, and strong, weighing more than 200 pounds. So he turned back around and kept walking. But the shouting followed him, growing louder, closer, more aggressive. Shepherd’s annoyance turned to agitation—he turned around, telling the man to fuck off, to get away from him. Dismounting from his bike, the man walked towards Shepherd.

“I had about five seconds to either fight or flight. And I sized him up and I realized, well, I can run from this man, but he has a bike and he’s just going to chase me down. Or I can stand my ground.”

So he did. The man lunged at Shepherd, still shouting slurs, and a fight ensued—Shepherd hitting back with his umbrella, calling for help, asking passersby on the trail to intervene. No one did. The fight wasn’t longer than five minutes, though in the moment, “it felt like it was going on forever.” It was only after Shepherd was able to punch the man in the face, drawing blood, that the two separated.

Shepherd knew he needed to call the police. What had happened, he was realizing, could very well be considered a hate crime. He could see, to his confusion, that the man was already dialling 911. The two men, just a few yards apart, each called the police.

Ten minutes went by, and firefighters arrived, checking them both for injuries. Another 25 minutes passed with no sign of the police. Without a word, the man who assaulted him got on his bike and rode away. The firefighters told Shepherd that judging from the amount of time that had passed, it was unlikely anyone was coming. They told him to go home.

Shepherd waited on the trail another 20 minutes while his friend brought him a new shirt—his had been torn up during the fight—and in all that time, the police never arrived. To this day, they haven’t followed up, despite Shepherd’s cousin tagging the Toronto Police Service (TPS) Twitter account in a widely-circulated thread about the incident.

“This is our taxpayers’ dollars at work,” Shepherd says. “It’s disheartening, it’s upsetting, and it doesn’t make sense. Why are we putting so much money and trust into a system that continuously fails, over and over and over again?”

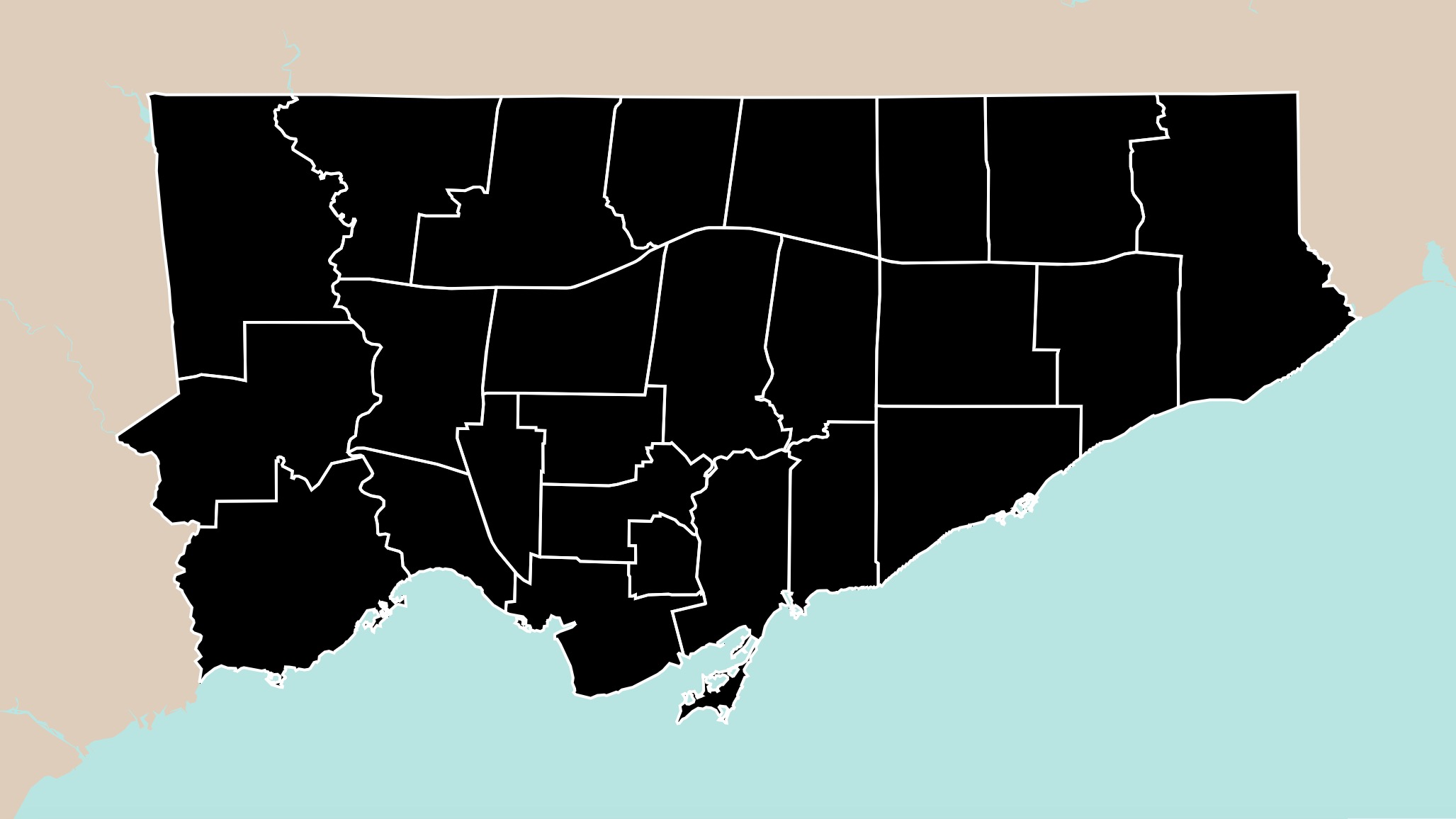

That failure is systemic. A June report by Toronto’s Auditor General found that TPS’s response time to a Priority 1 emergency—the most urgent calls they receive, involving existing or imminent harm, like a shooting, ongoing assault, break-in, or a person with a weapon—has averaged between 15 and 20 minutes for the past five years. Priority 2, in which the threat of loss of life or injury is still imminent, has an average response time of between 40 and 50 minutes. The target response times for these calls, set by the Toronto police themselves, is 6 minutes, a goal the police are failing to meet in the vast majority of cases. And the wait times only grow from there, reaching 300 minutes or more on less urgent calls.

The police are one of the most heavily funded public services in Toronto, taking up a mammoth $1.1 billion in 2022, consistently hovering around one-tenth of the city’s total operating budget in recent years. On an average Toronto property tax bill, more money is directed towards Toronto’s policing budget than any other single line item. Why, then, are they failing in one of their fundamental responsibilities—to respond when people need them?

The failure is the result of a series of cascading crises: a lack of adequate social services, public over-reliance on the police, the inequitable and skewed priorities of law enforcement, and the unwillingness of city council to divert funding to where it could do more good. The TPS police budget costs the city a lot—and the inefficacy of the police force is costing Toronto residents even more.

When you call the police, you expect them to answer—it’s the first thing many people are taught about emergency response. But more and more people in the city are finding otherwise. The Local spoke with Torontonians who have been left waiting hours during potentially life-altering events like break-ins, assaults, domestic disputes, overdoses, and mental health crises.

Philip Mills, a Scarborough resident and father of two, experienced a domestic incident in which he worried for the well-being of not only himself but multiple children in the house. When he called the police, firefighters showed up first, arriving within 15 minutes. The aggressor in the incident, a family member, took this as an opportunity to continue threatening Mills. “They’re not here to protect you,” he yelled. “They can’t.” The police didn’t arrive until three hours later.

In July, Nicolas Bello, a 49-year-old resident of the Annex, called the police after seeing an elderly Asian man being beaten in Alexandra Park. Four hours later, after the assailant had disappeared, the elderly man’s injuries had been tended to, and Bello was safely at home, the police called and left him a voicemail. “We’re at the park,” they said. “Are you still here?”

It takes just a moment for an incident like this to turn deadly. In June 2018, police received a call saying that a man was being beaten up in Parkdale. It took paramedics 45 minutes to arrive at the scene and take the victim—a man in his 50s named Joseph Perron—to the hospital. The police only arrived three or four hours after that—by then, Perron had died in hospital, leaving his daughter to wonder what would have happened if he had received timely attention.

“The Service welcomes the 51 recommendations made by the Auditor General,” a spokesperson for TPS told The Local. “We have admittedly experienced some struggles when it comes to responding to some calls in a timely fashion due to a number of resource-driven factors, and this is something we are aggressively working to improve upon.”

It’s easy to say that the answer to poor response times is increased police funding—but it’s not that simple. Between 2018 and 2019, for example, there was a $30 million increase in funding to TPS, funding that then-police chief Mark Saunders said would be used to hire new officers. But in 2019, wait times continued to increase compared to the year prior.

It’s hard to make other comparisons for previous years. The available data for TPS response times is limited to five years, two of which saw no increase in budget, and two of which had their rates of police calls and responses impacted by COVID. But even when compared to other cities, there is no clear relationship between funding and efficient response times. For instance, while Toronto operates with a smaller number of police officers per capita than some other Canadian cities, it has the fourth-highest rate of spending on police per population size in the country. Municipalities with higher rates of spending on police, like Vancouver and Edmonton, did have faster response times—but so did cities with smaller rates of expenditure, like Ottawa and Montreal. While it’s tricky to compare response times between cities, since police jurisdictions don’t always measure priority levels and response times in the same way, Toronto’s average response time is significantly higher than comparable major cities like Vancouver, Ottawa, and Montreal, whose average response times in 2019 were around ten, seven, and five minutes respectively.

Response times aren’t as much about money and personnel as they are about how many calls the police are receiving at once, the urgency with which they have to arrive at the scene based on information from the dispatcher and the caller, and their obligation to see a call through once on-scene. The problem, according to the Auditor General’s report, is that the city’s police are being called to far too many scenes at which their presence isn’t actually necessary. When the police are responding to calls about, for example, the presence of an unhoused person at a business, a noise complaint, or a dispute between a landlord and tenant, a queue of more serious calls is building up. The report makes a conservative estimate that if even some of these calls are redirected towards non-police responders, the police force could save an estimated 85,000 staff hours over a five-year period.

This is something everyone agrees on, from police abolitionists to the police themselves: the police are in a lot of places they don’t need to be.

“Clearly, we have to do some deep thinking about how we allocate resources, and to what tasks, right across all the services we offer in the city,” says councillor Gord Perks, one of city council’s most vocal champions for redirecting police funding.

“I’ve actually talked to a lot of police officers who will ask me directly, ‘Why am I, with my particular skill set and training, spending so much of my time looking after health care problems…being dispatched to every overdose? This is not useful policing, this is not stuff I’m trained at, it’s not the best use of my time.’”

Support a Civic Newsroom Like No Other

This story is part of our Toronto Election 2022 coverage. It’s a hugely ambitious project with a simple aim: to keep Torontonians informed about the important, hyperlocal issues not covered anywhere else. If you like what we’re doing, please consider supporting The Local. Your donation comes with a charitable tax receipt.

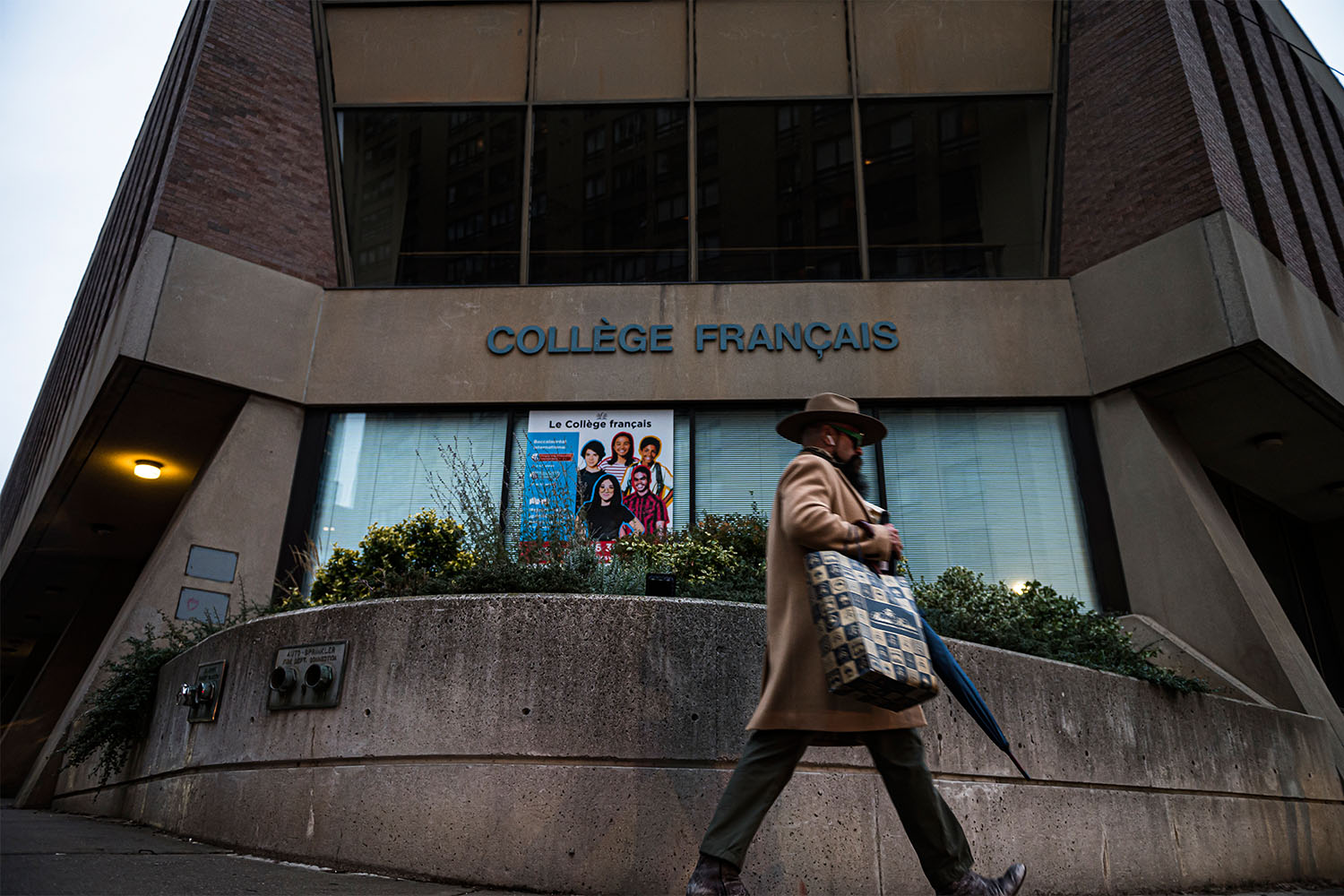

SupportThe city’s recent non-police crisis response pilot projects were created with that reality in mind. The Toronto Community Crisis Service (TCCS), which launched earlier this year, started with a city council motion in 2020 to explore options for non-police responses to mental health calls—calls made to the police by, or on behalf of, people experiencing distress. The discussion was informed in part by the massive mobilization of the Black Lives Matter movement following both the killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police and, in Toronto, the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet while police were responding to a call in her home—and more broadly, by the disproportionate harm police have been found to inflict on both Black and Indigenous people and those with mental health issues.

A 2018 report by the Ontario Human Rights Commission found that between 2013 and 2017, Black people were 20 times more likely than white people to be killed in a shooting by TPS, and that civilians with mental health concerns made up a third of TPS’ use-of-force incidents. This pattern is part of a national crisis—in 2020 alone, there were nine fatal police shootings that began as wellness checks. Data released by the police this year confirms that racialized people, especially Black and Indigenous people, are disproportionately subject to use of force and strip searches by the police.

“We heard in consultation that folks didn’t feel safe calling into 911,” says Saige McMahon, who leads one of the four TCCS pilot projects happening in the city. “Even just based off the experience they’ve had when they have called police, or when police have been called on them.”

In a collaboration between 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations, ENAGB Indigenous Youth Agency, and the Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre, McMahon’s team runs the city’s downtown west pilot, also known as Kamaamwizme wii Naagidiwendiiying, which means “coming together to heal, look after and take care of each other” in Anishinaabemowin.

The program responds to calls for mental health support from the downtown west 24 hours a day, every day of the week, and additionally specializes in providing traditional and culturally relevant forms of support for Indigenous callers. When someone calls 911 from within their boundaries for support in a mental health intervention, they’re asked whether they’d like to be redirected to 211, the helpline specializing in providing community supports and resources. People can also call 211 directly. From there, McMahon’s team decides whether they’re able to attend, and members of the team are dispatched in groups of two or four, providing support alongside essential needs like food, water, adequate clothing, and options for shelter. The person in crisis has the option to join their case management system, which provides longer term support.

This and three other pilot projects are operating downtown and in northeastern and northwestern Toronto. The budget for the four pilot projects was $11 million, just one percent of the total policing budget. But even if they were better funded, just having a robust non-police response isn’t enough—there needs to be a fundamental move, both by civilians and law enforcement, away from seeing the police as the default response when something goes wrong in the city.

When people call 911, it’s often because they don’t know what other resource or service to access. That’s what happens when police in a city are better funded than any social service. But community workers, especially those working with racialized communities or supporting people with mental health or substance use concerns, have repeatedly said that the presence of the police can escalate crises rather than resolve them—escalation that McMahon’s team, in contrast, almost never sees.

The idea that callers with mental health or substance use concerns pose some inherent kind of danger to first responders—despite the fact that they instead are disproportionately more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators, both in general and specifically at the hands of police—has been used to justify the use and expansion of police forces for a long time.

There needs to be a fundamental move, both by civilians and law enforcement, away from seeing the police as the default response when something goes wrong in the city.

Before the TCCS pilots, there were the city’s mobile crisis intervention teams, a project that began in 2000 and expanded across the city, pairing a mental health nurse with a uniformed officer to address mental health crisis calls together. But by default, police still responded to the scene first, making sure that there was no risk of violence. This hybrid response, which is still in place in much of the city, doesn’t actually address the problem of slow police response times. It’s not that there aren’t ever any dangerous mental health or substance use calls—it’s simply that the assumption of inherent danger has been a disservice to vulnerable communities, and has led to this system-wide ineffectiveness among police.

The assumption of danger has also crept outward into the behaviour of other first responders. The Auditor General’s report calls for a reassessment of the relationship between paramedics and police officers. In a type of police call named “See Ambulance,” paramedics can request police presence on a call they believe could be dangerous. This is understandable, and paramedics shouldn’t be expected to risk their lives to provide support. But the report points out that in many of the calls audited there was no clear indication of why police presence was necessary, or whether it could be justified.

“While Toronto Paramedic Services procedures require call takers to clearly document the reasons for police notification,” the report reads, “we could not locate a clear rationale for requesting police in almost all of the call for service documentation reviewed.”

One of the key factors the report mentions regarding See Ambulance calls is the presence of alcohol—something that doesn’t inherently present a danger. Instead, it seems like the stigma around substance use, even a substance as common as alcohol, is informing paramedics’ responses to particular calls. Such a situation could have a serious impact on the well-being of the subject of the call, especially if urgent medical attention is required. If paramedics can’t attend a call, and are left waiting for a response from a police force with chronic delays, the patient’s health suffers.

When asked for comment, a spokesperson for the city’s Paramedic Services said, “Emergency Medical Dispatchers and Paramedics use their skills and experience to identify potentially dangerous situations which, when proactively assessed with police, can be defused or prevented from escalating.”

“Toronto Paramedic Services will continue to work with Toronto Police to refine requests for police attendance to ensure appropriate rationale in situations where patient and/or staff safety may be at risk.”

At the heart of the police response time issue is a more fundamental question: why have the police become the default answer to so many kinds of problems? When it comes to mental health, distress, or overdose calls, the most obvious answer is that the city’s social services haven’t grown to meet demand, particularly when it comes to housing, mental health supports, and substance use. In the face of strained services that sometimes have to turn away people seeking support, the still robustly funded police service becomes the go-to response for crisis calls borne from chronic, systemic issues.

There’s also the problem of non-urgent calls to the police—things like non-violent disputes between landlords and tenants, or disagreements among family members or neighbours. Many of these calls don’t need to be attended by police, and take an average of more than an hour to clear, when they could instead be handled by services built specifically for them: family counsellors, housing lawyers, the city’s 311 service. But that takes some amount of individual responsibility, and a collective reckoning: if the public wants a more timely response in emergencies, it also has to grapple with its over-reliance on the police in non-emergencies.

Beyond that, there’s an incongruity between the police’s claims of being overburdened and their choices; the police say they suffer when their system is overburdened with non-emergency calls, but the actions of the police—particularly the police union—have played a significant role in getting the city to this point, as have the decisions of municipal politicians and decision makers.

In 2017, the city’s Transformational Task Force, organized by the TPS board, put out a report regarding a reduction in police spending, the downloading of non-emergency responsibilities onto other city departments, and the importance of redirecting non-emergency calls. But the police labour union, the Toronto Police Association, pushed back, saying that any reduction in police officers would only worsen response times, and that the budget was in peril, ignoring the fact that response times are decided not by how much money a police department has, but by how they organize themselves. Reassessing what calls police should respond to involves answering the question of what fundamental value the police bring to a given incident—and there’s a reluctance among pro-policing voices to have that conversation.

Even now, advocates for non-police response services are pointing out that not enough calls are being redirected from 911 to the non-emergency line. The mental health crisis lines have a much greater capacity than is being used, in part due to a reluctance by the police and 911 dispatchers to trust the crisis response teams. One staff superintendent with the TPS told the CBC that police were still engaged in trying to “build up [officers’] confidence that there is an alternate response to some of these events,” and doing the same for the callers who have refused to be diverted because they feel police are the only appropriate response. Mental and social divestment from police needs to happen not only at the institutional level, but at the level of those they serve, and that will take intensive public messaging. The TCCS pilot projects won’t succeed without that push to spread the word about non-police alternatives, and affirm the value of non-police alternatives among the police themselves.

This is the problem with maintaining a non-police response system within the city’s existing police infrastructure, says University of Toronto professor Beverly Bain, organizer with the police abolition coalition No Pride in Policing.

“[Law enforcement are] the first people collecting this information,” says Bain. “And they will then decide where [to] deploy their police officers, and whether this is something considered ‘dangerous’ enough that they should be part of the team.”

There’s also a question of feasibility. Currently, 911 dispatchers are the ones taking the call and deciding whether or not to redirect it, and they’re facing their own crisis of slow response times. Can we expect dispatchers under these conditions, stressed, rushed, and overworked, to take the time to ask methodical questions and assess whether the level of danger is enough to require police intervention? How often are they falling back to their default training, under which they’ve been operating for years—to go straight to deploying police?

When reached for comment, TPS did not indicate what, if any, special training is given to 911 dispatchers with the introduction of the TCCS pilot projects. “[TCCS] have our full support as we try to reduce the over-reliance on police for non-emergency calls, so we can better devote our resources to other critical policing functions,” they said in a statement. “We are learning, and what clearly falls within the scope of crisis workers and not police will sharpen over time.”

The responsibility to make better choices falls not only to the police, but also to the municipal politicians funding them.

Activists have also pointed out that it’s difficult to understand how TPS can complain about being overburdened when they’re expending time and resources on issues better addressed by improved social supports and infrastructure—including recent crackdowns on encampments in city parks, and the over-policing of cyclists in High Park.

“Poor and disenfranchised people are seen as a danger to the rest of society, to those who are middle and upper class, and to businesses and property,” says Bain. “[The police] will choose to go into those situations because they consider those people dangerous.”

And amidst all this, despite the police acknowledging that responsibilities need to be reassessed, there’s still an unwillingness to reckon with the police’s inflated budget.

“They want to be excluded from those situations, which we were asking for them to be excluded from anyway,” says Bain. “Except money is not being divested. It’s a de-tasking—money is just being re-allocated, re-circulated.”

The responsibility to make better choices falls not only to the police, but also to the municipal politicians funding them. Right now, spending more than $1 billion on police who rarely arrive on time, and often escalate conflicts when they do arrive, feels unjustifiable in a city where so many other social services are buckling under the strain of high demand and low funding. Redirecting the responsibility for non-emergency calls to other city services also means reconsidering how much of the city’s budget the police should receive. And yet, in this past city council term, all but a few progressive elected officials voted against multiple motions made to divert money from the massive TPS budget to social services that desperately needed it.

In 2022, council voted against diverting $10 million from the police to the city’s Shelter, Support and Housing Administration to bolster rent supplements, and in 2020 they voted against cutting the policing budget by 10 percent. Smaller motions, too, regarding diverting $250,000 each from the police budget to TransformTO and the city’s libraries, failed, as did a motion regarding phasing out mounted police for $6 million in savings. In contrast, a vote to implement body cameras for the city’s police—an initiative that is widely understood to be ineffective in preventing police brutality, and which TPS estimates could cost $50 million over the next decade—was passed.

When Councillor Josh Matlow put forward his 2020 motion to cut the police budget by 10 percent, he made an appeal to his fellow councillors. “What I’m asking you to do,” he said, “is show courage.”

Most of the people with a stake in this issue are more or less in agreement on what the problem is; where they differ is how bold they are willing to be in their approach to a solution. The alternative is the status quo—a billion dollar budget for police that don’t come when you need them.