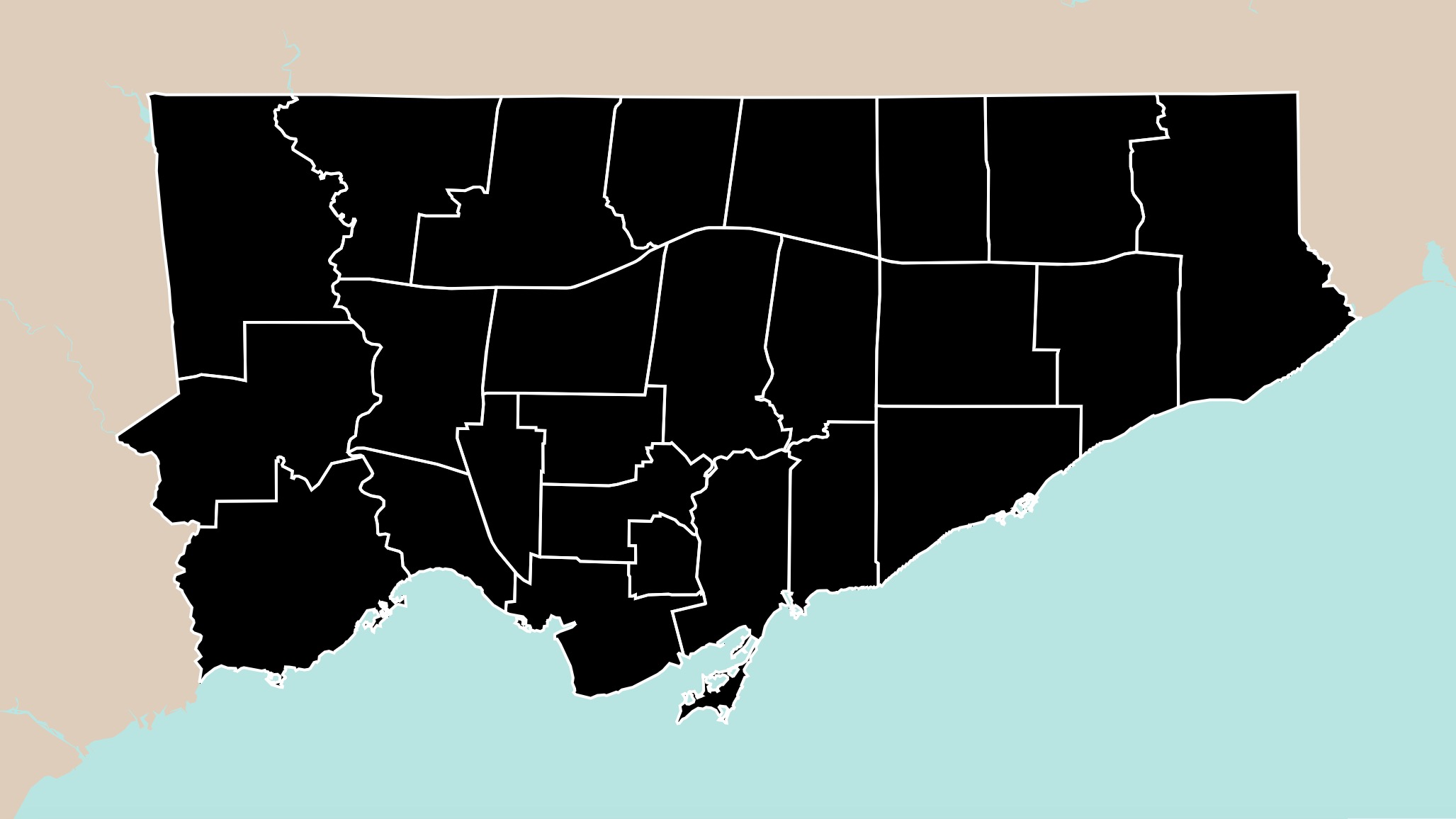

Wedged into Toronto’s west-end, Davenport is the only ward that crosses the Dupont tracks, linking a condo-lined stretch of Queen Street West with the bungalow-sprinkled hills of Fairbank south of Eglinton Avenue.

As a narrow bridge between Toronto’s inner city and its inner suburbs, it’s tempting to rely on well-worn stereotypes to make sense of the two ends of the post-2018 mega-ward. But dismissing the residents north of the track as Ford Nation and people to the south as Left-Wing Bike-Riding Pinkos ignores the archetypal Davenport voter, one often left out of Toronto’s polarized political narrative.

A self-proclaimed working class district with high rates of homeownership, the ward is home to a generation of immigrants who were able to purchase property when the market was cooler and kinder. Many of them are in unions and no stranger to collective action. But the skyrocketing cost of living and the city’s failure to address crumbling and overcrowded infrastructure has motivated an abandonment and distrust in government—the precise conditions that allowed the Ford dynasty to emerge.

“Organizing on the right is powerful. People have legitimate reasons to be angry,” explains Alejandra Bravo, a well-known entity running her fifth campaign in the area and fourth for city councillor. The 51-year old director at the Broadbent Institute was born in Chile and moved to Canada as a refugee at age three in the wake of Augusto Pinochet’s coup.

Left-wing populism, Bravo says, can be a useful response to that anger. “It recognizes that there is a material dimension to people’s grievances, without villainizing our neighbours and abandoning our institutions, which belong to all of us,” she says.

With long-time councillor Ana Bailão not seeking re-election this fall, the ward has an opportunity to take a chance on a candidate that doesn’t just play to the middle, as the former deputy mayor did so well. While frustratingly pragmatic to Davenport’s more progressive residents, Bailão’s acquiescence to Mayor John Tory on the police and encampment files may have advanced crucial victories in procuring more affordable housing.

“I’m going for the Rob Ford-Jack Layton voter,” says Bravo between door knocking on a humid afternoon in late August. Bravo continues to bet her political future on a voter typified by the relatively unknown and unlikely friendship between the two late and mythologized heroes of the right and left: when Rob Ford was first elected to Toronto City Council in 2000, then-councillor Jack Layton was the only person to take him seriously. (When Layton died in 2011, a teary-eyed Mayor Ford reflected on his legacy: “He never let the job go to his head…He really wanted to put a lot of money into the social services and the homeless programs.”)

It’s a message that is increasingly resonating in a ward that is skewing more progressive while maintaining its working-class self-image. While the north had a history of electing Rob Ford-ally Cesar Palacio, Bravo has increasingly narrowed the gap between first and second place in her five elections since 2003. In the 2019 Federal election, she ran for the NDP in the Davenport riding, losing by a mere 165 votes to Liberal Julie Dzerowicz.

As Bravo knows, elections are not predictable, but the winning candidate in Davenport will need to appeal to a voter that transcends formal political labels, speaking directly to residents on small issues that have larger implications.

See All Ward 9 Candidates

The Local’s Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked information about all candidates on the ballot for October 24’s election.

At first glance, not much distinguishes Grant Gonzales from Alejandra Bravo.

“I’m running as a candidate who has lived the housing affordability crisis,” says Gonzales, one of the many contenders for Davenport’s council seat appealing to the ward’s blue-collar residents.

“I have been priced out of my own community. It’s a problem when you can’t imagine yourself living in the neighbourhood you grew up in.”

Gonzales, 32, grew up in Brockton Village, and has been making his name known in the neighbourhood through his roles as the President at the Davenport-Perth Community Centre and co-chair at Pride Toronto. If elected, he would be the first Filipino-Canadian on Toronto City Council.

While Gonzales sounds a lot like Bravo on many issues, he is distinguishing himself in one crucial way: his photo with Mayor John Tory on the front page of his website where the two stand side-by-side, smiling with their thumbs up.

Gonzales’ eagerness to be associated with the likely next mayor of Toronto—along with an official endorsement by Tory—reveals the kind of councillor he is aspiring to be.

You can hear shades of Tory in his take on affordable housing, favouring an approach that loosens restrictions to make it easier for the private sector to build more.

“How are we incentivizing the construction of all forms of development?” asks Gonzales. “If it’s too expensive, developers aren’t going to build anything.”

It’s a clear appeal to the approach that made Ana Bailão a successful political entity in the ward for 12 years.

As deputy mayor and advocate for housing, Bailão was a major proponent of the City’s Housing Now initiative, securing over 5,000 affordable rental units on 21 city-owned parcels of land. Her critics maintain she didn’t go far enough, capitulating to modest densities in a city where the NIMBY proclivities of homeowner’s trump all.

While she was despised on the left for her timid victories on housing and soft stances on defunding the police, Bailão was a crucial bridge to John Tory—a patient pragmatism that may be the only way to accomplish anything progressive in Toronto.

“We need to go further on housing, but I will work constructively with the mayor,” assures Gonzales, appealing to those who aren’t ready to abandon Bailão’s formula.

“Ana left the ward in better shape,” Bravo agrees. “Now we’re going to push for things that challenge the complacency.”

“But pragmatism doesn’t mean compromise. Some things are non-negotiable,” says Bravo after reflecting on the ongoing violent clearing of encampments throughout the city. “We have an obligation to uphold human rights.”

“I’ve had a lot of time to think about the lines I won’t cross.”

While the major issues of this election loom large over Davenport—the crisis of affordability, the role of policing, and Doug Ford’s continued interference in municipal politics—the key to voter’s hearts in this west-end ward may be something a bit less existential.

“The amount of people that I meet that want to talk about parking is astonishing,” says Shaker Jamal, another candidate hoping to take over Ana Bailão’s vacant seat at city council.

Born in Afghanistan, Jamal moved to Canada as a refugee and grew up in Vancouver before moving to Toronto in 2012. While he’s a self-described progressive and advocate for worker’s rights, emphasizing his experience advocating for wage increases as a union representative on his website, Jamal has been spending an outsized amount of time hearing about the lack of parking in the ward while knocking doors and introducing himself to the neighbourhood.

Whether it’s parking, traffic congestion, or the water fountains that never work, the way Davenport’s new councillor addresses the little things will be a gateway to a more existential shift in how the ward is represented.

“While I’m canvassing, I’m hearing from people about what matters to them. It’s never right versus left,” says Jamal. “No one talks that way.”

It may explain how the archetypal hybrid voter in Davenport is a card-carrying member of Ford Nation who also wants to redirect the police budget to fix the seemingly endless potholes in the city. Jamal is tapping into the populist anger that is bubbling out of a broken city—but not by giving up on a collective response as our way out of this mess.

“I find it ludicrous that we fund $6 million on police horses but I can’t go to a park and find a functioning water fountain,” says Jamal.

He’s another candidate appealing to the blue-collar self-image of the ward. “I’ve always been working class,” he reflects. “The powerful and rich people don’t need my help—there’s enough people looking out for them. I’m interested in working for regular people.”

Jamal wants to go beyond Bailão’s pragmatic but limited approach to policy making. He is campaigning on new tools, like housing bonds which leverage city assets to invest in the construction of deeply affordable housing, citing Portland, Oregon’s recent instatement of the financing tool as an experiment worth repeating in Toronto. He is also proposing a new Housing Commissioner role to ensure someone is accountable to the success and failures of Toronto’s housing initiatives.

Those big-picture and outside the box ideas, however, aren’t ultimately what will decide who becomes the city councillor in a ward that bridges so many distinct landscapes and contradictory political identities. While anger and apathy are common amongst voters no matter their political affiliations, at the door, constituents aren’t talking about housing bonds, they’re talking about parking spots—small things that will play a big role in determining the future of the district.