On a sweltering day in early September, Colin Mahovlich stepped into the lobby of a 10-storey apartment tower on Roanoke Road in Parkwoods-Donalda, a neighbourhood nestled on the east side of the Don Valley Parkway in Ward 16 — Don Valley East.

Just one floor of the tower is the equivalent of canvassing about a dozen bungalows, but Mahovlich—a 28-year-old former customer service representative running for city council, and a renter himself—wasn’t expecting a lot of handshaking or talk from the tenants inside. “Frankly, from my observations, a lot of them are tired,” he said. “They are working. They don’t want, or have the time, to spend listening to some guy who’s promising them rent’s going to go down if they support these policies over the next 10 years.”

About 20 doors in, Gaylynn Trotter, a 70-year-old retiree, opened her door. Mahovlich launched into his campaign spiel about building more affordable housing in Ward 16 to lower rents. Trotter listened quietly. She lives in the apartment with her husband, 72-year-old Joseph Trotter, and their son, who moved in with them because he couldn’t afford to get his own place. “We pay a lot in here,” she said. “There’s four of us living in this one bedroom. It’s pretty rough.”

The family has managed to remain in their unit, but it hasn’t been easy. “Forget about saving,” she said. “My pension cheque goes in the front door and out the back door.”

The Trotters are like so many residents of Ward 16. According to 2016 census data, around 55 percent of Don Valley East residents rent, compared to 45 percent who own their own properties. Squeezed by decades of single-family zoning policy, the replacement of older apartment towers with luxury condo developments, and gentrification around the Eglinton Crosstown LRT project, tenants like the Trotters are facing ballooning rents.

Yet for the last 28 years, the residents here have been represented by Denzil Minnan-Wong, an unabashedly pro-homeowner councillor with a long history of penny-pinching on municipal infrastructure and services. The councillor has been one of the most vocal critics in Toronto of rooming houses and transitional housing projects in spite of the city’s rental housing crisis.

When Minnan-Wong announced in July he wouldn’t run for a ninth term in office, he told residents he had tried to represent both homeowners and tenants alike during his tenure. But his sympathies were clear. “In this regard, I remain a proud and unapologetic defender of property owners’ rights,” he wrote in his resignation statement. “The next Council needs to listen and show a greater sensitivity toward property owners and their communities.” (Minnan-Wong, through a staff member, declined to comment for this story).

This October, residents will elect a new councillor, one of the 11 candidates running for office who all make vaguely promising comments on front door mats about improving affordability, city services, and amenities for the area. But the question here, and across the city, is how do you elect someone who will actually look out for the interests of people with landlords, rather than just the landlords themselves? In a city dominated by the politics of homeowners, who speaks for the renters?

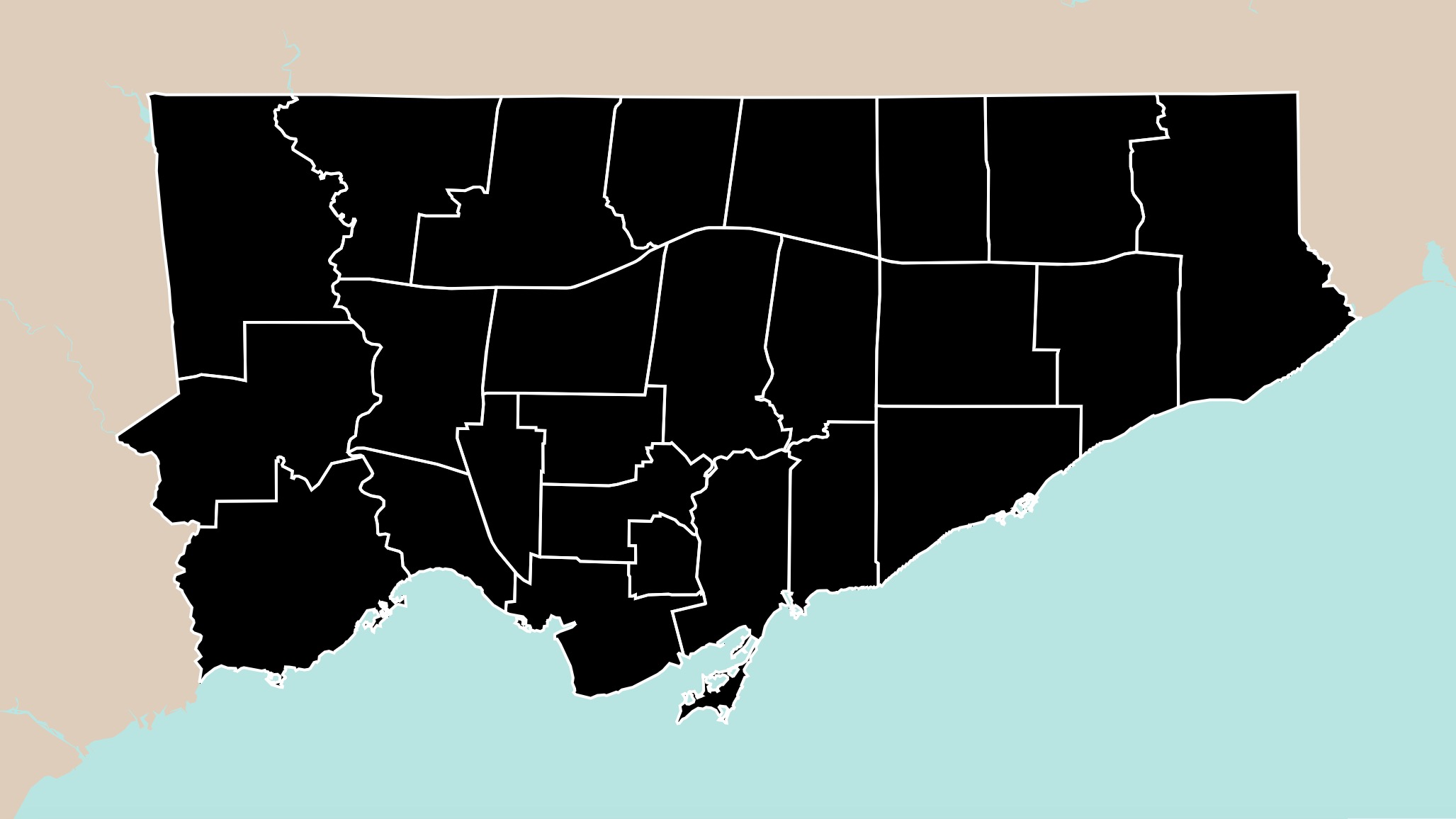

See All Ward 16 Candidates

Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked biographies of all 11 Ward 16 candidates.

Stand just outside the Ontario Science Centre and look east and you’ll notice the tall apartment and office towers of Flemington Park looming over parking lots and wide thoroughfares. But venture into the winding suburban streets of Don Mills, not too far away, and you’ll find a very different neighbourhood: impeccably kept bungalows, multi-storey McMansions and aging midrise apartments. Roughly 25 percent of Don Mills’ population lives below the poverty line, while the neighbourhood’s average property price is north of $1.5 million. As with all of Toronto, Ward 16 contains multitudes.

Rent prices are far too high everywhere in Toronto, but Ward 16 shouldn’t, in theory, be as tumultuous a market as the denser downtown wards. The Eglinton Crosstown still isn’t online yet and Don Valley East’s condo market isn’t as hot as those of Liberty Village or Yonge and Eglinton. That said, Ward 16’s average rent in 2016 was $1,200 a month. Just over half of all tenant households at the time spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs. The pandemic saw a slowdown of rent prices, but since 2021, Toronto rents have surged again. In June, Bloomberg News reported they’d increased 20 percent since last year.

Don Valley Community Legal Services gets calls from all over Ward 16 from tenants. Bhavin Bilimoria, the clinic’s director of legal services, says they see all kinds of cases—from evictions over unpaid rent to tenants bothering one another or causing safety concerns in their buildings. But the biggest share of cases by far are arrears cases—either tenants trying to preemptively lawyer up to avoid eviction, or a landlord taking them to the Landlord Tenant Board. “The arrears [cases] are just blowing everything out of the water,” he says. According to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s 2021 national rental housing report, Torontonians need to work an average of 35 hours a week at the city’s average wage just to pay for a two-bedroom rental apartment on 30 percent of their income. Renting in Toronto simply isn’t affordable for many low-income renters, and some are falling behind.

Landlords also frequently neglect basic repairs. Bilimoria says some landlords are behind on maintenance but are still applying for rent increases above the provincial guideline to do large-scale capital repair projects. But the reshaping of Ward 16’s cityscape will also challenge the area’s renters, both present and future.

Nearly all residential neighbourhoods in Don Valley East are solely dedicated to single-family homes. Developers looking to get rich on high-volume tower complexes opt to buy unused land or older apartment towers, demolish them, and set up luxury condo units well out of the price range of many renters. While the law requires developers to replace all the rental units they destroy, they aren’t required to add any new apartments to grow rental stock—a serious problem in a city with a 1.8 percent vacancy rate.

“Does the city die when you make it so unaffordable that people can’t live in the city?” asks Stephen Ksiazek, another Ward 16 candidate. Ksiazek is the former president of the Don Mills Residents Association and owner of a foundation and waterproofing business, and he is razor-focused on ensuring new residential developments include public amenities like playgrounds and community centres for residents. On his campaign website, he also acknowledges the need for better snow removal service, tackling Toronto’s affordable housing crisis, and expanding transit.

An influx of high-density luxury condo towers into Ward 16 concerns him, especially the way in which they displace rental housing. Metro Park, a series of towers and townhouses at 25 Saint Dennis Drive, will add 552 units total. But Ksiazek says it’ll only replace the 167 rental units that once stood on the site; the rest will be condos starting in the $600,000 range. Just up the road, at the corner of Eglinton Ave East and Don Mills, a 60-acre development called Crosstown Place will add just shy of 5,000 residential units to the area by 2023—a mix of townhouses and high-rise units along with retail and office space. According to Crosstown Place’s website, prices start at $911,990.

“Half of the dwellings in central Don Mills are apartments,” Ksiazek explains. The city needs more housing, and he says many residents simply cannot afford to own property. “We need more rental, we need more housing geared to income, which we don’t have enough of,” he says. “But a lot of these [new developments] are not aimed at that at all. They’re strictly condos.”

That said, there are housing projects breaking ground in Ward 16 that Ksiazek doesn’t oppose. One is a five-building tower complex on either side of Don Mills, just north of Eglinton, reaching up to 48 storeys, all overlooking the new Eglinton Crosstown LRT. “There’s rent-geared-to-income, there’s low-income, there’s some condos in there,” he says. “It’s a real mix.”

Given all the issues renters face in Ward 16, why would a majority of voters vote for someone like Minnan-Wong—a councillor who disapproved of highrise housing expansion, rooming houses, and other methods of easing the rental affordability crisis for eight straight elections?

Part of the problem is that renters can sometimes literally be hard to reach. While candidates hold barbeques and other out-of-home campaign events, the time-honoured tradition of going door-to-door with flyers and slogans can be a difficult way to reach renters. When Mahovlich arrived at the Roanoke apartment tower late that September afternoon, he had to call the rental office at another site for access, only to find that everyone had already left the office for the day. A local resident who happened to be sitting in the lobby as Mahovlich fiddled with the keypad let him in.

Difficulty accessing apartment towers doesn’t stop committed candidates. On top of canvassing, some candidates build bridges with local residents (renter or otherwise) through community events or just hanging out in the neighbourhood. Others pointedly seek out renters as an untapped voter base.

Walter Alvarez-Bardales, a Ward 16 candidate on leave from the Canada Revenue Agency, puts issues of poverty at the very top of his platform. A refugee from Guatemala, he fled to Canada in his late teens and spent time living on the streets, an experience he still finds difficult to talk about today. Addressing issues like rising rents and Toronto’s criminalization of homeless people, rather than just homeowners, is very important to him. “I’ve seen a lack of compassion, a lack of sensitivity, a lack of availability from the councillor,” Alvarez-Bardales said of Minnan-Wong.

While he believes renters could be critical to winning Ward 16, he suspects they are overwhelmed by the sheer number of elections Toronto residents have faced in the last year. Turnout in municipal elections is always the lowest of the three orders of government—just 41 percent of eligible Toronto residents voted in 2018. Some renters are simply too busy to care. Others work multiple jobs, have childcare responsibilities, or are just drained when a candidate comes knocking. “Unfortunately, they don’t have the energy, nor the time sometimes, to understand how important and vital it is for city services to elect the right councillors,” Alvarez-Bardales said.

Then there’s the question of whether renters are able to vote in the first place. Non-citizens pay taxes, but cannot cast ballots, and there is a huge immigrant population in Ward 16’s apartment towers. Flemingdon Park is home to a multitude of communities—Eastern European, Somalian, South Asian, Afghani—and recent arrivals are far more likely to be renters than owners. Language barriers might also present a challenge. As Bilimoria points out, renters in Ward 16’s immigrant communities might not necessarily speak English as a first language. “I think that folks are less knowledgeable about their rights, and also how to go about enforcing their rights,” he says. If tenants have trouble understanding the eviction process, voting in an election may be lower on their priority list.

The very issues driving Toronto voters to the polls also happen to be biased towards homeowner concerns. Property taxes, snow removal, and garbage collection all affect renters to some degree, but their landlords are the ones paying the bills and maintaining their properties. Nearly all tenant concerns around rent are the province’s jurisdiction and, therefore, out of a councillor’s purview.

Add all of these issues together, and some renters might be willing to vote for a councillor like Denzil Minnan-Wong, or simply ignore the election altogether. Of course, renters aren’t a monolith. Some oppose policies with the potential to lower rent, like more apartment towers. As one woman told Mahovlich on his way out of the Roanoke Road building: “Have you worked recently downtown? It’s a disaster,” she says. The buildings are just too tight. “If you don’t have eggs at home, you can go to your balcony and ask your neighbour—it’s that close.”

The candidate with the most name recognition, and likely the frontrunner, is Jon Burnside. An ex-police officer who served in Flemingdon Park, he eventually won a council seat and served on Mayor John Tory’s executive committee in his first term. Community safety is high on his list of priorities, but so is tempering what Burnside sees as the hysteria of rapid housing development at the expense of slow, methodical, careful neighbourhood planning. “We have to make sure that what we’re doing is going to work for everybody,” he said.

Burnside brings up Toronto’s Official Plan, a blueprint for how the city should develop transit and land while also respecting the environment. He points out it calls for neighbourhood “character” to be protected: in other words, sprawling suburban communities shouldn’t need to put up with high-rise development in their midst. Burnside initially characterizes this as destroying a neighbourhood, before retracting it in favour of saying they “change the character” of areas. “There’s lots of cheap land like Lawrence Avenue east of Victoria Park,” he says. “There are lots of ways to be creative and build supply without altering the characteristics of neighbourhoods.”

As a former councillor for Flemingdon Park, Burnside understands the maintenance issues faced by tenants in older buildings. But while he promises to fight for both renters and homeowners alike, his vision for Ward 16’s rental market is one that may make it even tougher to bring in new rental housing at a time when the citywide vacancy rate is close to zero. Without more units, prices will remain high, forcing lower-income renters like the Trotters to either move in with each other or leave Toronto entirely.

After 14 years living in their apartment, all of which was spent under Minnan-Wong’s previous terms, Joseph Trotter is skeptical about promises that a new councillor could push through more housing and lower rent costs. Even so, Gaylynn Trotter and her husband will cast her ballot this fall, like they do every single election. As she says: “Our thinking is—if you don’t, keep your mouth shut.”