On New Year’s Day, The Local launched RAT Tracker, a tool for anonymous reporting of rapid antigen test results among students in Toronto’s public schools. It was created to solve an emerging data problem: in a memo to school boards on December 30, the province announced it would no longer report COVID cases in schools, which it had done since the pandemic began.

Even prior to the announcement, our collective understanding of Omicron—its prevalence and whereabouts in the city—had become murky due to capacity limitations in the laboratory PCR testing system, the primary source of COVID surveillance data. This all happened at a time when parents, students, and education workers needed more, not less, information about the safety of schools.

The premise of RAT Tracker was simple. A total of 11 million rapid antigen tests were handed out to Ontario students for screening purposes before the two-week winter break. This meant that the RAT system had 10 times the daily capacity of the PCR system (around 75,000 tests per day). And yet, there was no data coming back to help fill the black hole in the surveillance system. It felt like a huge missed opportunity. RAT Tracker asked participants to anonymously report their test results, attempting to use the two million tests distributed to Toronto students to assemble a picture of COVID across the city’s public school system.

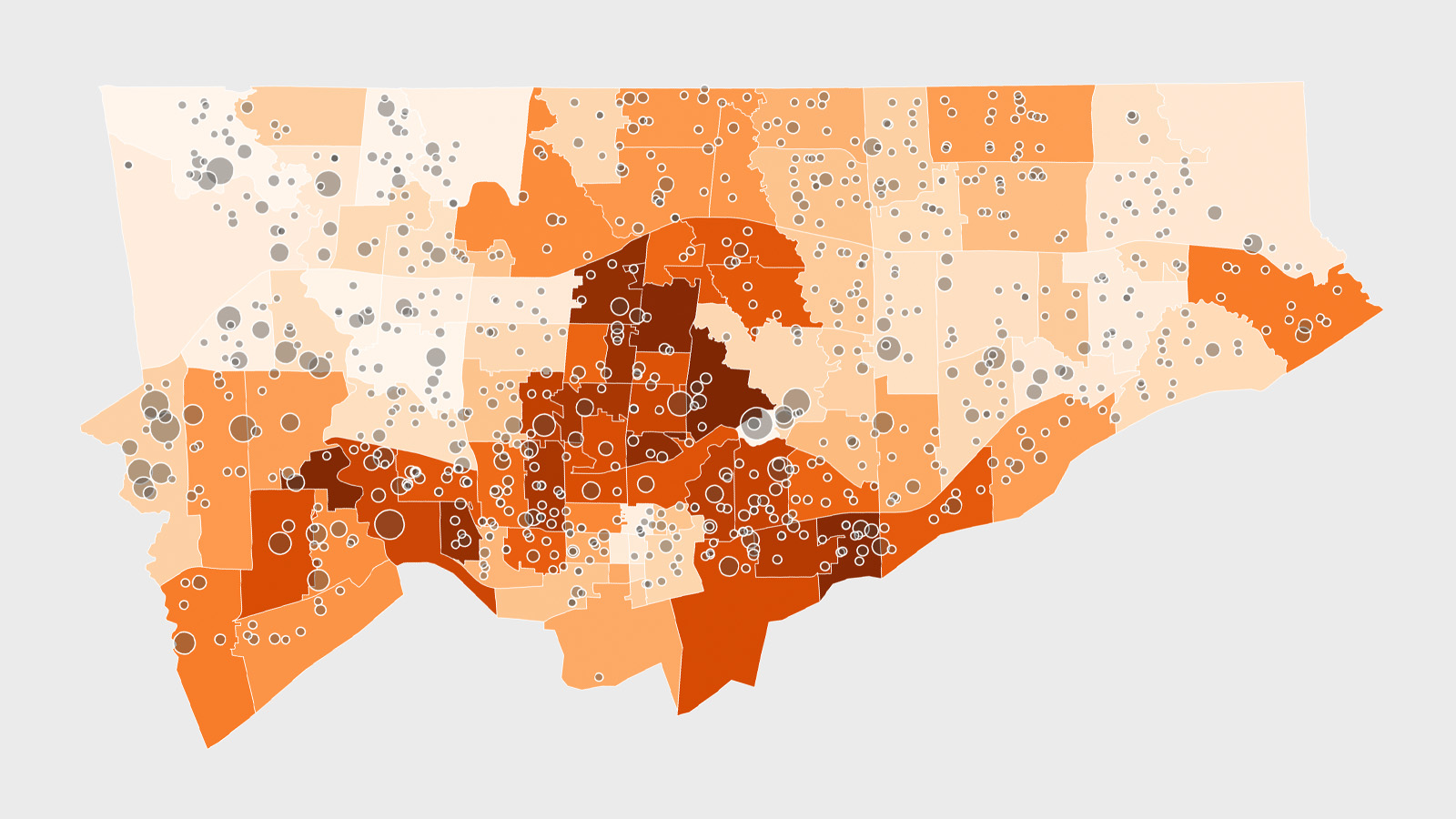

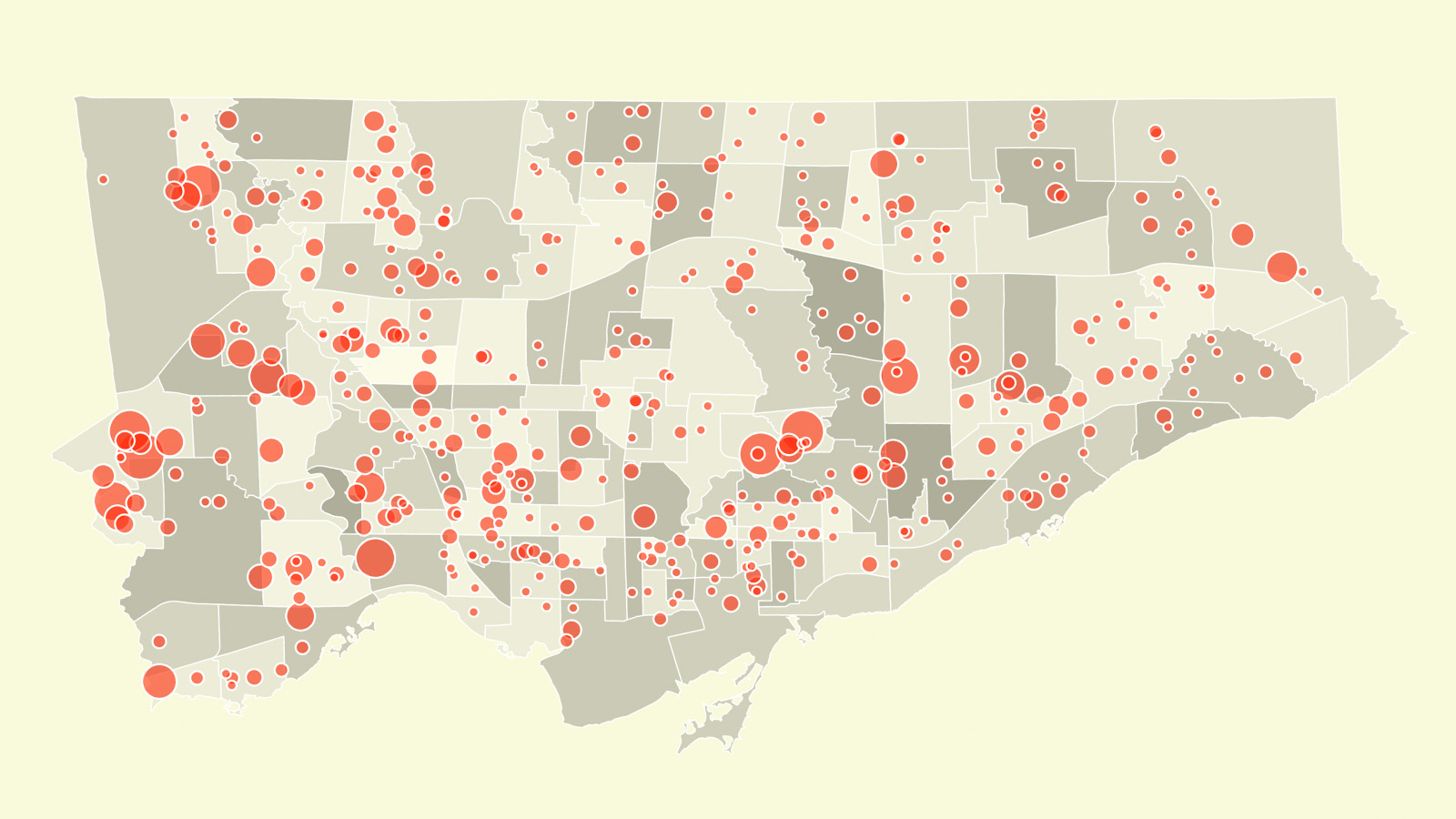

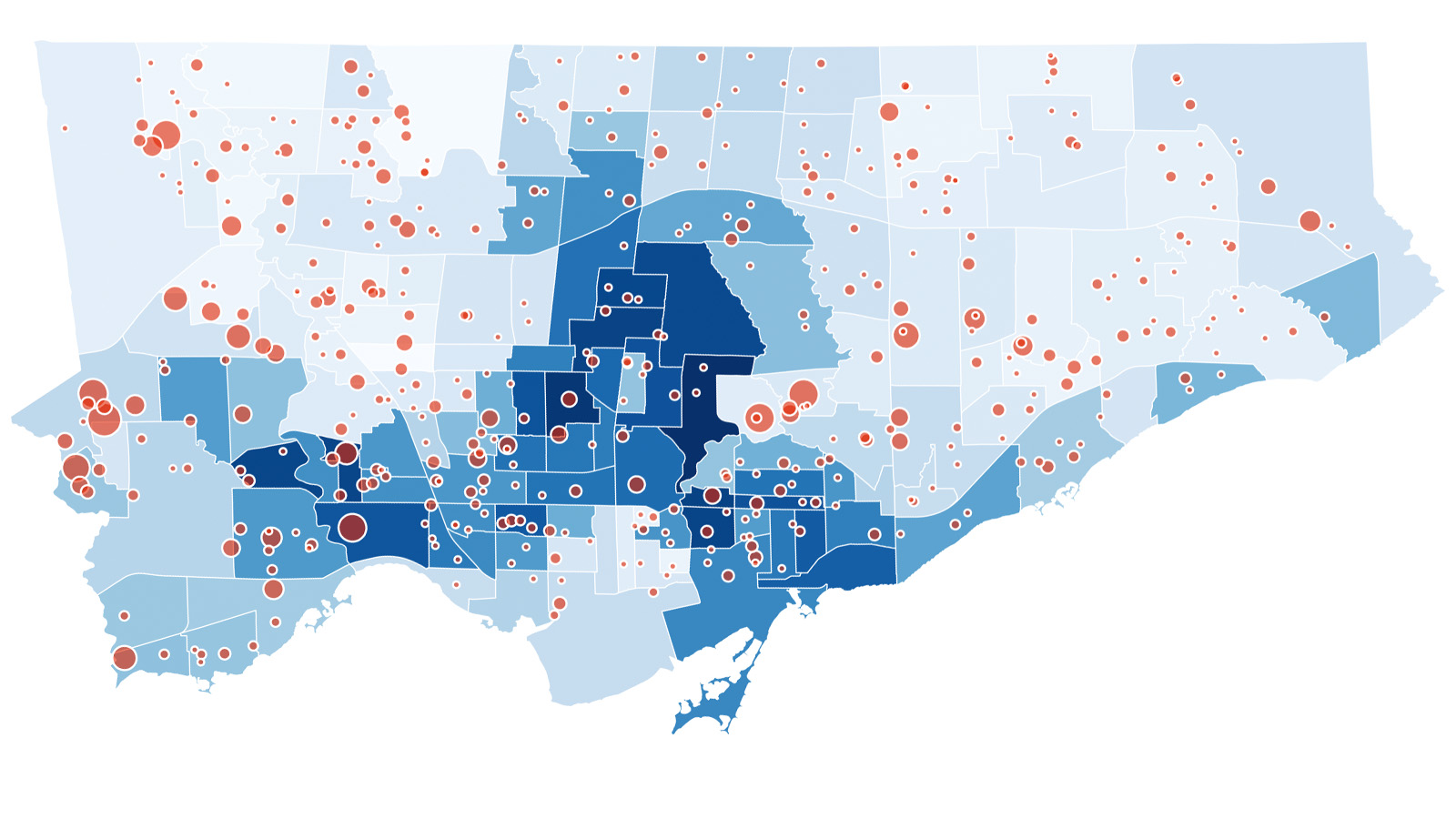

After 11 days, unfortunately, RAT Tracker has failed to deliver on that ambition. In its first week of operation, our tracker received a total of 2,665 test results. The data included positive and negative results for tests completed as far back as December 17, the start of the winter break. For context, Toronto’s public school system—the largest in the country—has close to 400,000 students spread out across 800 schools. The number of test results obtained is disappointingly low despite widespread media (CityNews, Global News, CBC, Scarborough Mirror) and social media attention about the project.

The results at the school level are presented here for transparency purposes. The data has significant limitations and should not be relied upon for decision-making.

The data is more reliable when aggregated up to the city level. It shows a city-wide test positivity rate of 32.0 percent between December 17 and January 9. This is comparable to the 32.7 percent captured through the laboratory PCR system, as reported by Toronto Public Health for the week ending January 1 (the latest available data).

We shared the RAT Tracker data with Jeff Kwong, a Toronto family physician and epidemiologist with ICES, the not-for-profit research organization formerly known as the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Kwong was encouraged by the fact that the overall results obtained through RAT Tracker mirrored those of the laboratory PCR system. “It would be ideal if they are matching and that seems to be the case,” he said.

However, Kwong thinks that the sample would need to be a lot larger for it to be useful at the school level. According to him, it’s also important to ensure that the sample is representative of the school populations across the city. The fact that RAT Tracker received fewer submissions from Scarborough and Toronto’s northwest than from central areas of the city is problematic. “If you have a biased sample, you can draw the wrong conclusions from it,” he said.

Kwong thinks that the best way to get good data is for the province to collect it. “In an ideal world, they would’ve done it where everyone submits test results using a portal of some sort,” he said.

When done at a provincial level, it could achieve scale and yield more reliable data, even if participation was voluntary. “Maybe we don’t need every single person to do it or every single school to participate. Even if you have a subset of schools and a substantial number of students participating, that’s still worthwhile,” said Kwong.

Ontario’s Ministry of Health did not respond to The Local’s questions about why the province did not provide a way for parents to report the results of the tests.

Two years into the pandemic, the idea of collecting information from rapid tests is hardly novel. In early 2020, the Creative Destruction Lab (CDL), a non-profit out of the Rotman School of Management, was already thinking about COVID as two related but distinct problems. For those who contracted the virus, of course, it was a health problem. “But for everyone else it was an information problem,” said Sonia Sennik, executive director of CDL. “You don’t know if I have it, I don’t know if you have it, so we lock things down or use blunt instruments because we don’t have information.”

The CDL partnered with 12 Canadian corporations—places like Air Canada, Rogers, and MLSE—to form the Rapid Screening Consortium, developing guidelines and protocols for securely reporting asymptomatic test results.

This kind of screening isn’t novel for schools either. At University of Toronto Schools, one of many private schools that has used rapid test screening for months, students used an app to report the results of their tests every Monday and Thursday this fall. (Initially, the tests were provided by the Ontario government, but since September the school has bought them directly from Abbot). The program caught five COVID-positive students, later confirmed by PCR. “We stopped the infection at that point,” said school nurse Adi Sood. “There’s a lot of value in these tests.”

In New York City—with a public school system of one million students, nearly half the size of Ontario’s—they test 20 percent of students each week as part of a random surveillance testing program. School-by-school test results are displayed on a single website managed by the Department of Education. Although the surveillance program uses PCR tests, which are more resource intensive to implement, the concept is the same: combine widespread testing with data collection to generate useful information.

In order for the full value of COVID tests to be realized in Ontario, the province needs to make data collection a priority.

On Monday, the province announced that students will be returning to schools on January 17, as planned. That means many parents will be making difficult decisions over the coming days with very little information. Some might choose to keep their kids home, while others will simply want to know what kind of environment their children will be walking into.

Implemented by the government, a simple program like RAT Tracker could have provided valuable information to school boards, students, and parents. Instead, we’ve been left completely in the dark.

Last week, the federal government announced they are sending 54 million rapid tests to Ontario, presenting the province with another opportunity to make them part of the overall surveillance system. This could be easily done by providing a link to a government portal where results could be reported. The link could be included with each test kit, thereby overcoming the challenges we faced when trying to reach people after the fact.

Without the government, however, it feels unlikely that efforts by citizen data-collectors can meaningfully fill the void. Within hours of launching RAT Tracker, scores of other test tracking initiatives popped up—from industrious seventeen-year-olds with Excel spreadsheets, hospitals desperate for information, and citizens looking for data in Peel, Hamilton, and British Columbia. The proliferation of these sites is a testament to how hungry the public is for data in the middle of an information blackout. But their sheer number, duplicating each other’s efforts and with varying levels of security, is also a clear indication of the limitations of this kind of ad-hoc data collection.

RAT Tracker has been an interesting experiment in citizen-led data journalism. But an online magazine cannot, ultimately, do the work of COVID surveillance. For that, you need the government.