When news broke of a fatal shooting in a Toronto high school on February 14, it was impossible not to think of the last time this happened.

Jahiem Robinson, a grade 12 student at David and Mary Thomson Collegiate Institute, was shot and killed at the school minutes after the final bell rang. Fifteen years before him, on the other side of town at around the same time of day, grade 9 student Jordan Manners was fatally shot at C. W. Jefferys Collegiate Institute.

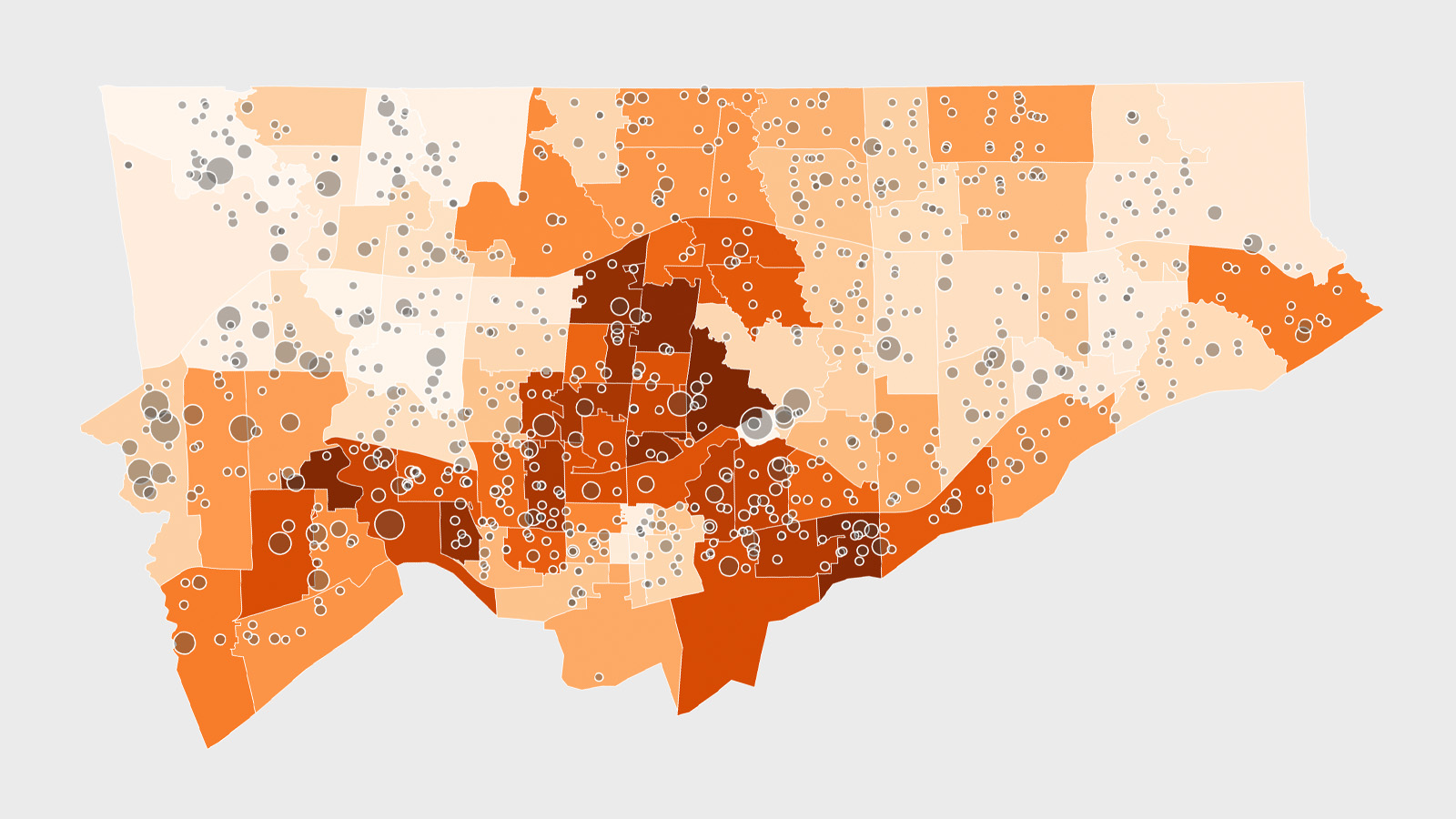

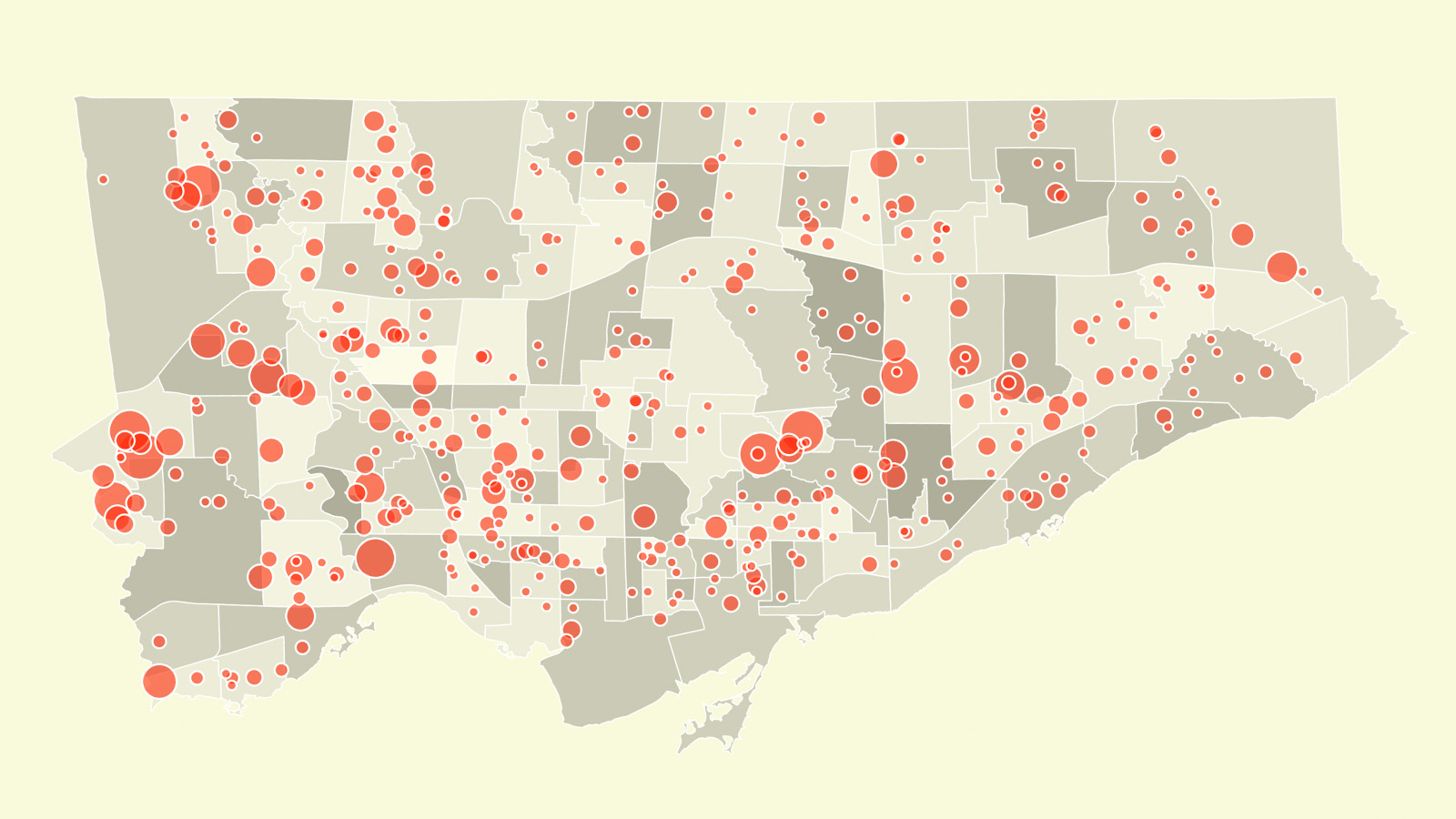

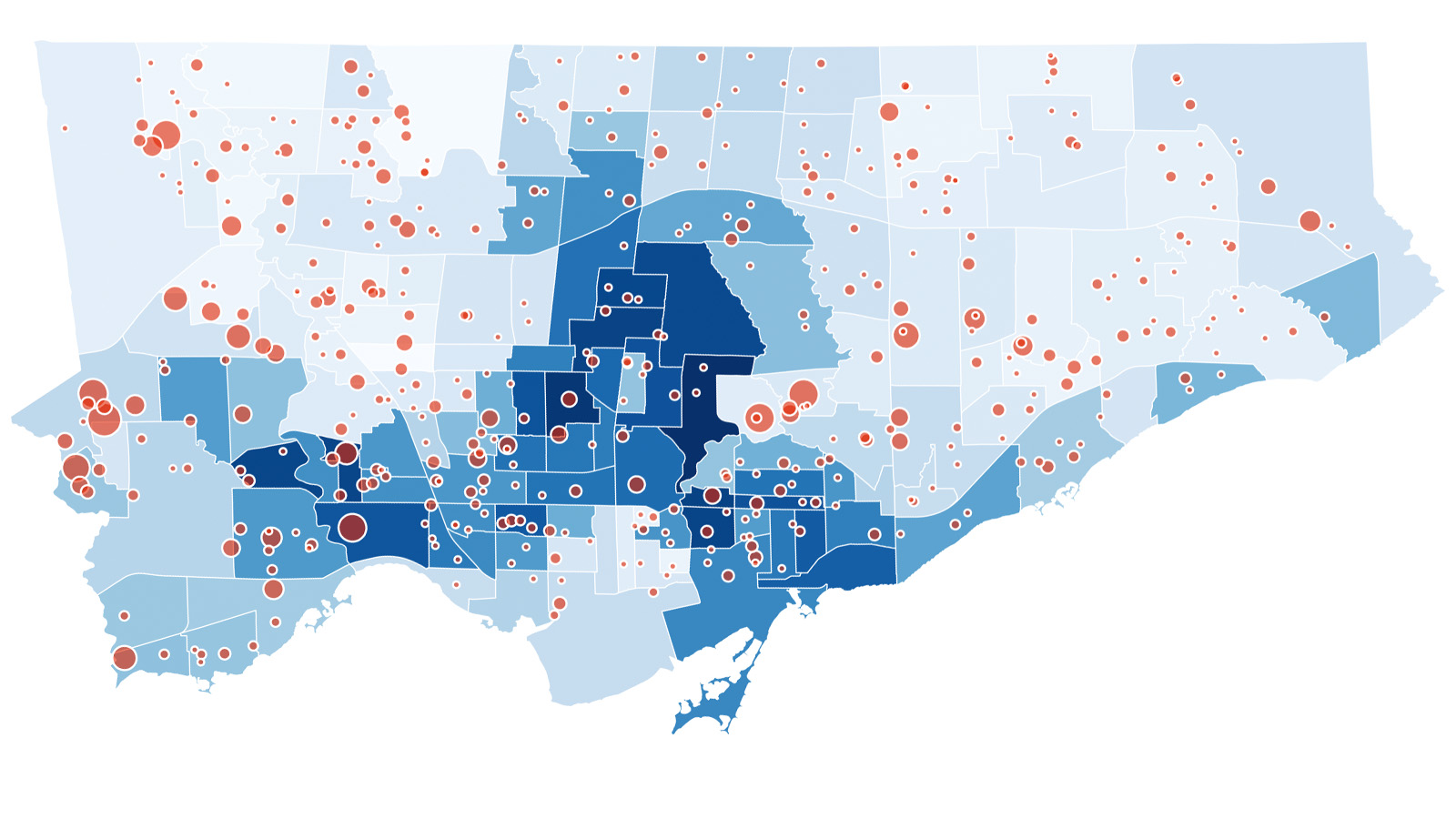

At first glance, these may feel like isolated incidents. But in the time between the two fatal shootings, there has been an alarming rise in violent incidents in schools. The Local’s analysis of TDSB data has found that between 2014 and 2019, the number of physical assaults in schools that required medical attention rose by 174 percent, and incidents involving the use of a weapon by a student to threaten or cause harm rose by 60 percent.

In the same period, the number of students bringing weapons into schools has also grown. The data shows that in the 2019/20 school year, suspensions on the basis of weapons possession made up a greater proportion of all TDSB suspensions than they had in the five years prior (the period for which data is available). The year before that, the school board’s weapons possession suspensions had reached a 10-year high.

While no official count is available, The Local found reports of at least four violent incidents resulting in student deaths on or near Toronto schools during school hours since 2014.

It’s a tragedy every time this happens, says Tesfai Mengesha, co-executive director of Success Beyond Limits, a community support program for youth in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood that operates year-round at Westview Centennial secondary school. “These are manifestations of systems that have failed families, and a society that’s not meeting the needs of its communities,” he says.

And in the fifteen years since Manners’ death, despite the numerous reports commissioned, committees struck, and recommendations made, troublingly little has been done to address the root causes of violence in schools. It feels, to some, a little like history is repeating itself.

While February’s school shooting didn’t happen in Mengesha’s neighbourhood, it did impact young Black students, a community with whom he works regularly. And when that happens, Mengesha’s first instinct is to ask what comes next.

“I get really worried about where this is going to take us,” Mengesha says. Already, he’s hearing conversations about the re-introduction of police into schools. “That conversation is really alarming—we know based on the failures of having police officers in schools in the past, that’s not going to solve the problem. It just exacerbates it, because we know that Black and racialized folks are targeted by police.”

Having police in schools, Mengesha says, has the potential to turn any disciplinary matter into a criminal one, taking it out of the school’s hands. Some researchers have argued that police presence increases the likelihood of students being alienated from their school environments and criminalized for their behaviour, and that it reinforces systemic racism in schools. Even among those who do feel there could be benefits, the need to reevaluate how much we invest in policing is evident. The presence of police in schools doesn’t address the root causes of violence, Mengesha says: “actually, it’s a regression.”

That’s because we’ve been here before. Following the death of Jordan Manners, the TDSB commissioned an investigation and report by the School Community Safety Advisory Panel (SCSAP) on the creation of safer, more equitable and welcoming school environments, and the prevention of violence in schools. The panel released a comprehensive 1000-page report in 2008, with 126 recommendations spanning more equitable responses to complex-needs youth, better funding of support staff, softening and elimination of the punitive “zero tolerance” policies brought on by the Conservative provincial government, and more. What the panel didn’t recommend was police presence in schools.

Later that year, however, the TDSB introduced the School Resource Officer (SRO) program, which made designated space for armed, uniformed police officers at select high schools in the city—27 schools at the start of the program, and 45 by the end.

To many, it appeared that the SRO program was introduced in direct response to Manners’ death and the resulting report—it was reported as such at the time, though TDSB trustees also described it as a separate initiative by then-police chief Bill Blair. But to the chair of the SCSAP, prominent Canadian human rights lawyer Julian Falconer, the idea that the panel’s report (often referred to as the Falconer report) in any way recommended the introduction of the SRO program feels “absolutely ludicrous.”

“It told me that somebody didn’t read the report,” he says. For Falconer, the question of having police in schools isn’t binary: there are contexts in which communities can shape and lead the program, and necessary considerations like who is funding and controlling the endeavour. But part of the reason the report couldn’t provide a firmer answer on what would and wouldn’t work was because they faced resistance from the people in charge—from the police, the Ministry of Education, a majority of superintendents at the Board. At one point, authorities stopped meeting with the panel; in its final months, even the panel’s funding for the report was curtailed.

“What I noticed in doing that job was that, increasingly, the very people that wanted me to tell the truth then wanted me to shut up,” Falconer says. “When it gets too close to the bone, people have fears, and we experienced real resistance to talking about these issues.”

To many advocates for safer and more equitable schools, making police a regular fixture in schools epitomized the TDSB and the provincial government’s response to the Falconer report. The panel’s findings—recommendations about systemic inequities related to race, class and gender, issues of chronic under-funding and harmful punitive measures—were neglected in favour of the easier way out, or the way that involved fewer difficult questions about who we prioritize and how we fund and support young people.

The choices we make about resource allocation, about whose success to foster—it’s all a deliberate process, says Falconer. “We literally set our kids up for failure, and then we express great surprise when those failures manifest themselves in the kinds of tragedies that we see.”

It was only in 2017 that the TDSB eliminated the SRO program, following a report that catalogued and quantified students’ and community members’ perspectives, which have been echoed by advocates for nearly a decade: that enough students have felt uncomfortable, unsafe, discriminated against, and targeted by the the presence of armed police officers in their schools that the program should be discontinued.

The Falconer report received criticism from some advocates after its release. Local education advocacy group Education Action: Toronto argued that the report focused too much on increased bureaucracy and that some of the panel’s recommendations offered a softer version of the same surveillance that was already harming students.

But in many of their recommendations, the panel aligned with community advocates in arguing for greater funding from the provincial government, the hiring of social workers and support staff, more culturally-inclusive education, and an overhaul to the way gender-based violence is prevented and addressed.

A few of the 126 recommendations can be traced through the decade since the report’s release. The Board did create a Gender Based Violence Prevention department in 2009, the responsibilities of which have since been merged into the Student Equity Program Advisor role. In their annual Caring and Safe Schools reports, the Board does break down suspension statistics into student demographics for the purposes of accountability and reporting transparency, and overall, suspension rates are falling. And a school safety hotline was set up in early 2008—it appears to no longer be in service, though there’s an online form to report safety concerns, and the Board is currently developing a safety component for their app.

But for the most part, it’s difficult to tell how well—or poorly—the TDSB and the Ministry of Education have done in implementing the recommendations of not only the Falconer report, but subsequent similar reports, including the 2015 School Safety and Engaged Communities report, released after the stabbing death of Hamid Aminzada at North Albion Collegiate Institute. The TDSB told The Local it had previously conducted a review of its progress on the Falconer report’s recommendations, and is currently reviewing them once again, but couldn’t provide any documents relating to the review. There has been no public reporting on this progress—no 10-year review, no report card. In the 14 years since the report was released, Falconer hasn’t heard from any institutional body interested in following up. “The term I would use is ‘crickets’,” he says.

“For any piece of work that reflects recommendations for serious structural changes, you have to go back later and, in a real way, audit whether the change happened,” he continues. “There has to be an actual political will to do that. I don’t think there is.”

“We don’t need to see conversations or another commissioned report. We need to move to action”

This lack of follow-through feels like a failure on the part of education leadership in Toronto and across the province overall. To Falconer, it’s testament to the fact that while discourse today has improved significantly from 2007, the lack of action to match it feels even more frustrating.

All of this is happening, of course, at a time when the TDSB and other school boards across the province have had to contend with years of cuts to education funding, which have a compounded effect on students with more complex needs or who have been deemed at-risk. Since 2018 alone, we’ve seen provincial cuts in the millions to the Local Priorities Fund and to extracurricular programs intended to support those students.

As those additional supports are cut back, support staff also face increased workloads. A 2018 report by People for Education found that the province-wide average ratio for guidance counsellors was 396 students for every counsellor, and that the workforce was straining to address the mental health needs of students—all of that before the pandemic worsened circumstances for educators and students.

It’s not just school staff that are in need of more funding. Community partners—who run programs in affiliation with schools, tackling issues like eating disorders, addictions and substance use, or trauma—are in dire need of funding, says Shameen Sandhu, system leader for mental health at the TDSB. She began as a social worker at TDSB schools 12 years ago, and now supports and leads those staff in a managerial capacity.

“[These community programs] have huge waitlists because they themselves are not being funded,” she explains. While students remain on those waitlists, social workers have to provide interim supports. And because of the sheer number of schools that TDSB social workers have to cover, the support they provide “can’t be as advanced as we would want it to be,” Sandhu says.

During the pandemic, with the COVID-19 funding provided by the Ministry of Education, the TDSB was able to hire 16 new social workers, Sandhu tells us. But it’s not just about social workers themselves, but the network of longer-term supports that exists around them. It’s worth mentioning, she says, that there have been countless tragedies prevented by the work of support staff in and around schools. It’s hard to say whether we could prevent tragedies entirely—but we do know where the gaps are.

For Mengesha, it’s also about addressing the roots of violence that have been worsened by the pandemic: poverty, access to food, transportation, housing, employment, ties to the criminal justice system, and isolation from community supports.

“The resources that are available don’t match the growing inequities that we see in society,” he says, pointing to cuts to part-time jobs for youth, and the scrapping of a universal basic income pilot project. At this point, what are we doing to address the factors that may lead vulnerable young people to crime or violence? At a systemic level, certainly not enough—and much of what is working at this point is held together by community workers and on-the-ground staff.

As part of the TDSB’s COVID-19 recovery plan, the Board will be hiring 106 new support staff—social workers, counsellors, child and youth workers. But in response to Jahiem Robinson’s death, the Board is also planning yet another third-party school safety audit.

“We don’t need to see conversations or another commissioned report,” Mengesha says. “We need to move to action: we have all the information, we have the data, we have the reports that tell us how we address the issue.”

Violence in schools is a reflection of what’s happening in the external community. In 2021, the average age of people affiliated with gun violence in Toronto was 20 years old, a sharp and troubling drop from years prior. At a provincial level, the response to gun violence has been a greater focus on policing, security, and prosecution rather than on taking a public health approach to violence and prevention, something Toronto Public Health requested of all levels of government in 2019.

“We don’t see a lot of these issues in the compassionate light we need to,” Falconer says, pointing out that people in need are still derided by many for receiving social supports and funding.

“To the extent we’re talking about real solutions, you’re actually talking about solutions to racism, to poverty, to structural inequities. And we know there are things we’re not doing because the privileged would have to give things up.”