Just after 10 a.m. most days, Levana Ho, who teaches a class of students ages 9 to 12 with autism at a York Region school, gets a call from the office. Her last student has just arrived. At this point, he has missed out on free choice activities, independent calendar work, and morning circle. He has also only just eaten breakfast—it’s why he’s regularly late for school.

The student belongs to a single-parent household, and there isn’t enough time in the morning to support feeding him and ensuring he’s ready for school. This student also lives outside the bounds of the school from which he receives specialized education, as is common for many students with autism. On the few days he does arrive to class on time, he chants “Morning circle! Morning circle!” giddily awaiting his favourite activity.

“A food program could relieve a lot of stress for his family,” says Ho. The school at which she teaches is in an affluent area and does not have a subsidized meal program.

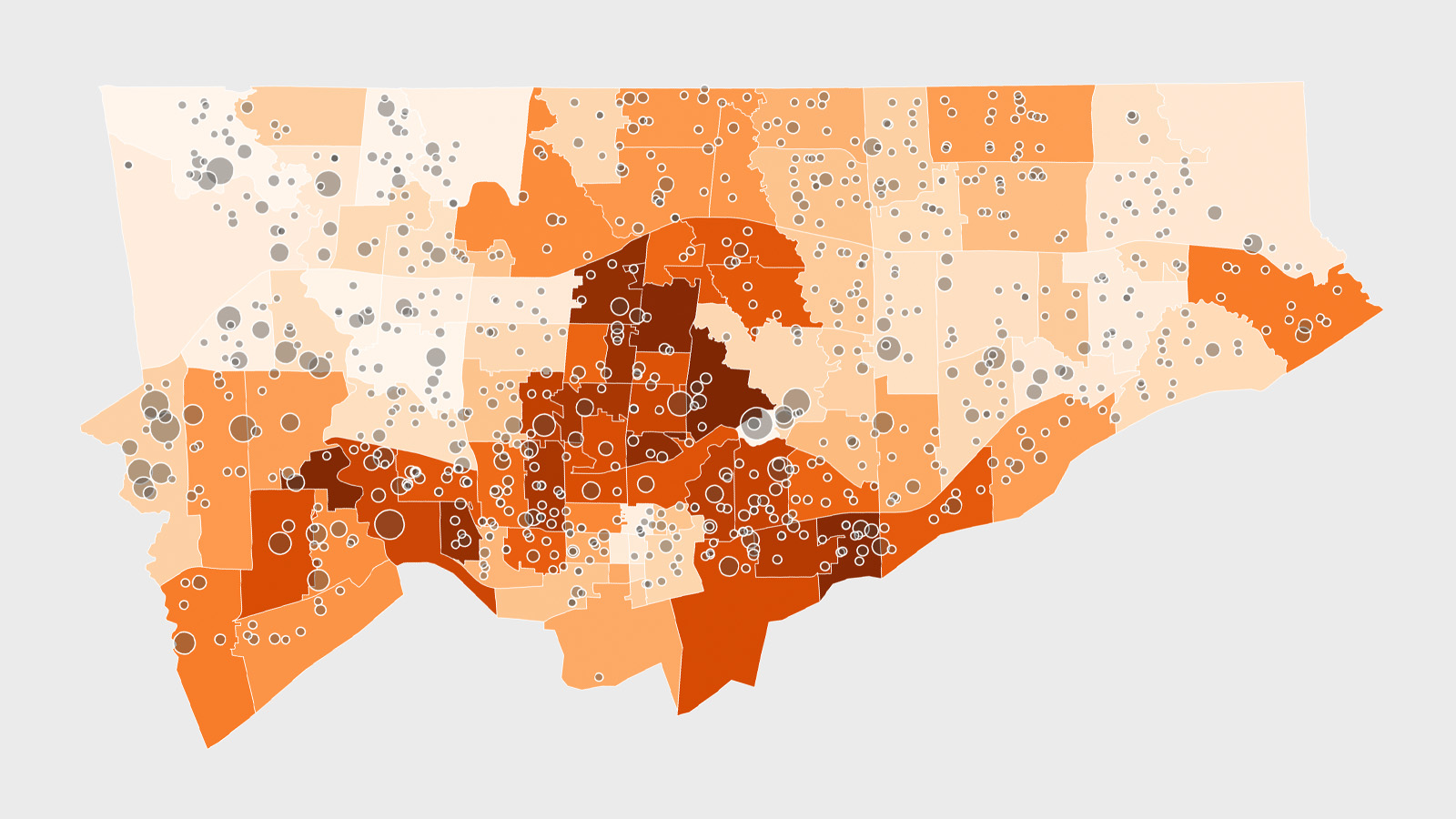

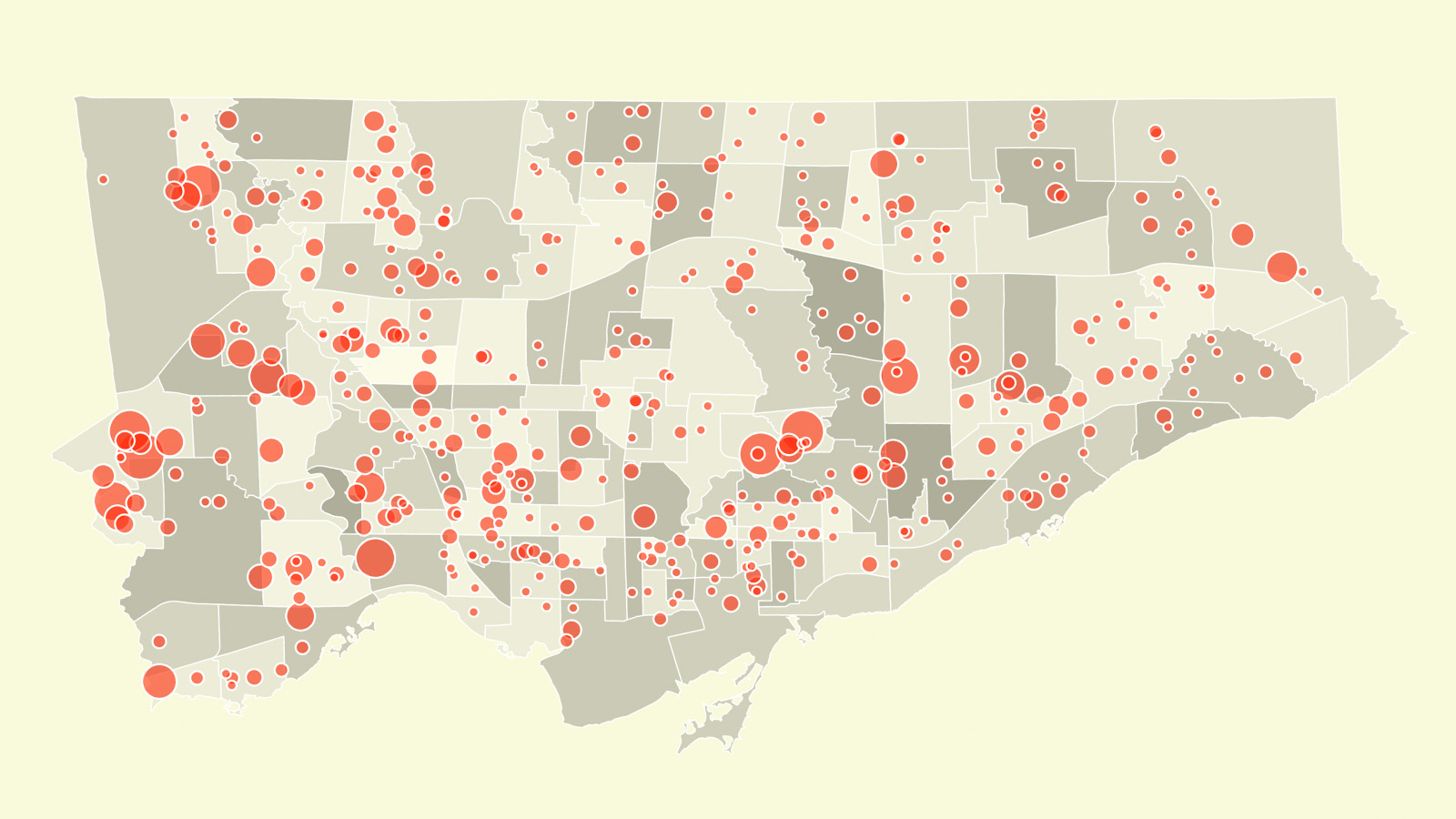

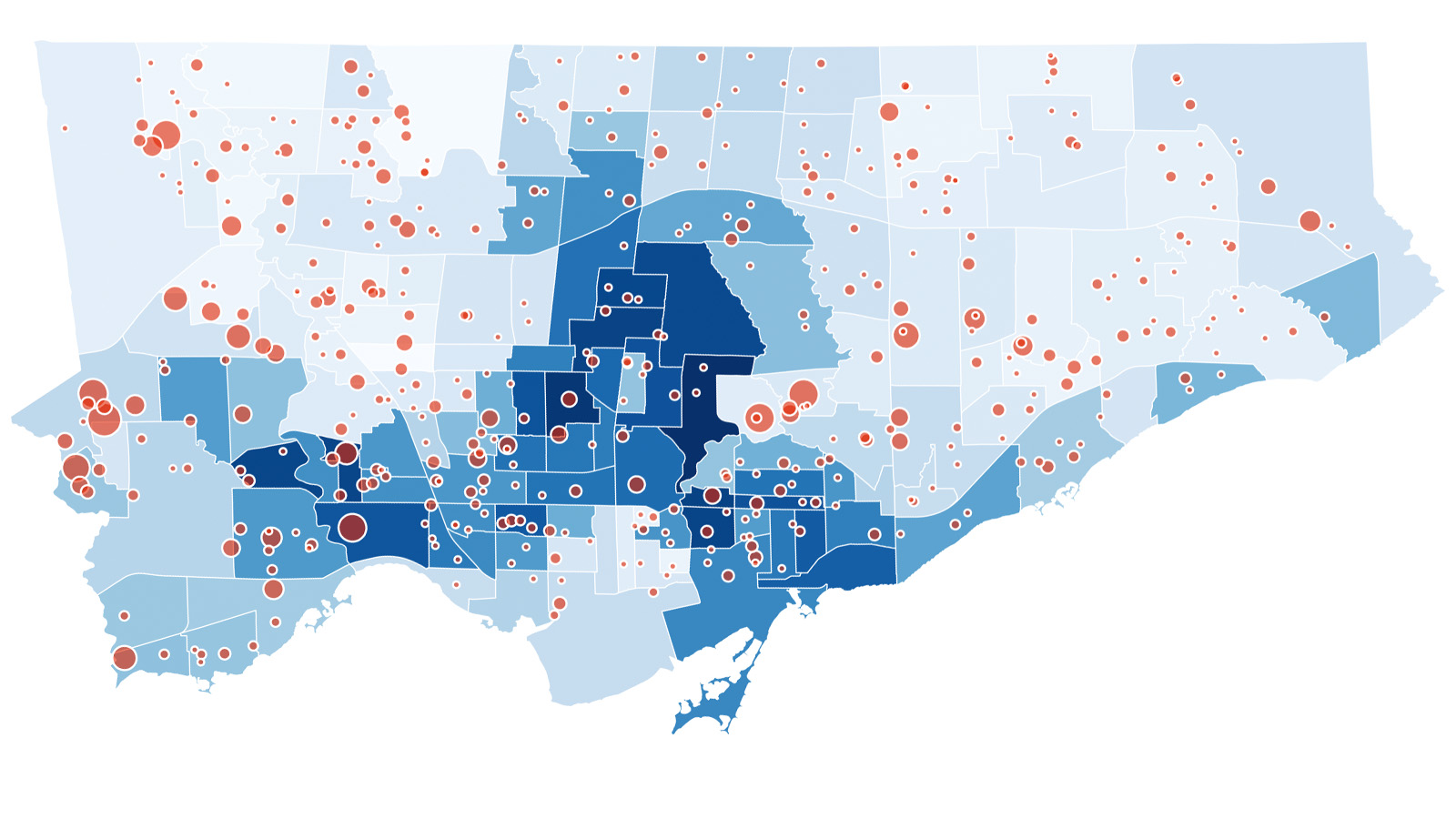

Canada does not have a national school food program. We are the only G7 nation without one, and in 2017, were ranked 37 out of 41 industrialized countries for food security among children by UNICEF. There is no centralized allocation of resources to support the nutrition of children across provinces and territories. In Ontario, funding for school food programs is provided by the province on a school-by-school basis, and their operations are outsourced to a handful of non-profit agencies. Each year, school administrators submit applications that estimate the number of lower-income students within their population; the applications are evaluated by these non-profit agencies, who then selectively allot funding to schools. Eligible schools are funded up to 80 percent of what’s requested with the expectation that the remaining 20 percent will be supplemented by the community, or parents.

While perhaps effective in servicing the immediate needs of hungry students, this piecemeal approach depends on food insecurity in underserved communities rather than sustainable solutions to eradicating it. A school’s food program is called into question every term, as student demographics change and boundaries shift. A gentrified neighbourhood that was once considered “lower-income”, for example, may not receive as much funding as it once did, despite students in need still attending the local school. This need-based model inevitably produces gaps, and for Ho’s students, limits participation, growth, and success in school.

Schools are where children spend half of their waking day. They are where young people form friendships, explore their identities, and develop interests and skills that shape their future. Beyond educational facilities, they are sites of personal and collective transformation. Hunger should not limit one’s ability to succeed in school. The call for a national school food program in Canada spans decades and is echoed by educators, parents, food scientists, farmers, and local restaurant owners alike—each of whom recognizes that student nutrition is essential to learning. A universal food program levels the playing field so that student success isn’t conditional on food security at home.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportOn Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, Westview Centennial Secondary School offers a lunch program. Before COVID, the spicy aroma of jerk chicken wafted from Room 129, the classroom-turned-lunchroom, where at least 140 students would gather among teachers to share a meal. These meals were outsourced from popular local restaurants, including students’ favourite, Caribbean Queen. Today, students collect the same meals in a grab-and-go fashion from the cafeteria.

Among these students are children that have been identified by guidance counsellors, social workers, or staff to be in need of meal support. They are pre-enrolled into this program and receive the meals free of charge. At lunchtime, it’s not apparent whose meal is supplemented and whose isn’t.

The school food program at Westview Centennial Secondary School is funded by the Toronto Foundation for Student Success (TFSS), a charity providing nutrition services to schools across the Toronto District School Board. TFSS is one of 14 agencies that receive funding from the province to administer student food and breakfast programs. In 2021, they received nearly $12 million from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services as well as $13 million from the City of Toronto. The funding enables TFSS to offer 815 school nutrition programs across the city, spanning breakfast, lunch, and after-school meals.

Dr. Monday Gala, the principal of Westview, would like to see the school’s lunch program expanded to five days a week and doubled in capacity. “I could do with more funding to feed my kids,” he says.

Gala has felt and observed the effects of a widely accessible school food program firsthand. In 2008, he was the vice principal at C.W. Jefferys Collegiate Institute, one of seven secondary and middle schools in the Jane and Finch area that participated in Feeding Our Future, a two-year pilot program by the TDSB. The program offered a free breakfast to every student who wished to participate, as opposed to just those deemed in need. The meals were administered in homeroom class every weekday at 10 a.m. and saw participation from the vast majority of students. The results of the program revealed significant improvement in student attendance, learning skills, likelihood to graduate, and academic performance, as well as a decrease in suspensions, tardiness, and behavioural issues.

“Every success indicator you can think of saw an improvement,” says Gala. “I remember when the Feeding Our Future report was released, it was covered by the national news. I thought at that time our nation would step up, but the funding levels for school food programs have not changed.”

“We need government ownership to make school food programs sustainable and robust,” says school food and policy researcher Dr. Amberley Ruetz. According to Ruetz’s research, there is a strong economic argument for a federally-resourced school food program. A “farm-to-school” approach that invests in domestic food purchases could contribute billions to the agricultural sector over time. “There’s great promise for what can be done in greenhouses and urban farms,” says Ruetz.

There’s also an opportunity for job creation. At present, school food programs depend on the volunteer capacity of staff and parents to place orders for meals, ensure food safety compliance, note allergy needs of students, and distribute meals to students. Over the pandemic, this capacity has thinned and resulted in the discontinuation of food programs across various schools. Ruetz estimates that, ideally, each of the approximately 15,000 elementary and high schools in Canada would have four food service staff to administer a school food program. This means the creation of 60,000 jobs and the stimulation of roles across the agricultural sector. Internationally, a cost-benefit analysis suggests a $3 to $10 return on every dollar invested in a school food program.

Debbie Field, national coordinator of the Coalition for Healthy School Food, has been advocating for a national school-based food program since her children were part of the TDSB in the 1990s. “School food programs are essential to being a part of a healthy society and resilient community,” she says. “And the good news is that we’re not starting from scratch. About a third of the children in Canada go to school with some semblance of a school food program.”

On the other side of the country, at Vancouver’s Lord Roberts Elementary school, weekly lunches are prepared and served by a group of grade six and seven students as part of a program called Lunch Labs. Under the guidance of former executive chef and current parent-volunteer Chef TJ, the students prepare balanced, plant-rich meals for about 200 students in their commercial-style kitchen. A fraction of the students being fed belong to lower-income families and receive the pay-what-you-can meals for free.

The architect of this program is Brent Mansfield, the edible education teacher at Lord Roberts. Lunch Labs is run in partnership with Growing Chefs and Fresh Roots, two non-profit organizations dedicated to food literacy and promoting local produce, and is primarily funded by the City of Vancouver.

Lunch Labs also aims to address a perhaps under-examined element of school-based food programming: the opportunity to cultivate a culture around healthy eating and local food sovereignty from a young age. According to Mansfield, students within Lunch Labs regularly make connections between their plates teeming with vegetables and local economies, as well as the cultural significance of certain ingredients.

Mansfield argues that Lunch Labs has the potential to be universal, but requires a shift in public investment to school-based food programs. “We don’t see food. It’s not valued enough,” he states. “School-food programs are therefore slapdash and designed to satisfy hunger rather than raise healthy children. What if we understood food as core to a child’s education?”

Yolanda B’Dacy, former kindergarten teacher and executive officer for wards two and four of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, says that programs like Lunch Labs, despite being well intentioned, could create their own disparities. “If children’s nutrition depends on a teacher or parent being amenable, open, and available, there will be some children that benefit from a rich, experiential program and others that don’t,” she says. B’Dacy’s concerns boil down to a question of labour. In its current state, provincial funding for school-based food programs does not account for the time, specialty skills, and resources required to successfully deliver meals to students. There is an implied understanding that staff and parent volunteers will overcommit themselves to ensure their children are fed.

In October 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s election platform included a commitment to spend $1 billion over five years to establish “a national school food policy and work towards a national school nutrition meal program.” In December 2021, he tasked the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food, Marie-Claude Bibeau, and Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, Karina Gould with this project.

But it is unclear what $1 billion over five years would achieve. Ruetz’s 2021 research found that if Canada were to implement a school food program comparable to Finland’s—where 95 percent of students partake in the program—$4.3 billion would need to be invested annually, more than twenty times the amount committed by the federal government. At present, there is little detail as to how a national school program will be implemented or when. The language regarding a national school food program in Canada’s first-ever food policy is also vague, stating only that the government will “work towards” such a program.

In the meantime, the cafeteria tables at Westview are lined with trays of rice and peas awaiting eager students, but only on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. For principal Gala, the kind of funding that will allow his school’s lunch program to run five days a week and be available to more students has been far too long in the making: “At this point, we just need to step up and feed kids.”