When Charlene Sutherland first got her job as an early childhood educator (ECE), she felt lucky. She was happy to be working at a not-for-profit that paid above-average wages, and she enjoyed taking care of the kids—creating epic theme days in the summers, watching their creativity shine through, seeing them help one another. “I went into this thinking, ‘I can make childcare a great career,’” she says. “And I did love working with the children—there are a few I still think about fondly, even now.”

“But,” she adds, “it came at a cost.”

A large part of that was financial. Working before- and after-care, she was given a split shift that only added up to part-time hours. In the mornings, she worked from 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m., then she came back for her afternoon shift from 3:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

She volunteered for any extra days she could, working Christmas break, PA days, and during summer programs. But it didn’t add up to enough to cover her bills. And so, in the middle of the day between her shifts, she would go to her second job, at Starbucks. That wasn’t uncommon—most of her co-workers had other jobs.

Childcare workers like Sutherland have been decrying the problems in their industry for decades. Low pay and a lack of benefits are standard. And those conditions have spurred an exodus from the industry, with high turnover rates, staffing shortages, and a lack of experienced workers.

Today, Ontario is the last province in the country without a child-care agreement with the federal government. Ottawa’s $30 billion, five-year plan promises to halve childcare costs immediately, and bring them down to $10-a-day by 2025. That prospect has parents salivating. But if a deal doesn’t improve working conditions for ECEs, any grand childcare redesign is doomed to failure. Now is the moment to address the long-standing problems that plague ECE work—changing the lives of workers and improving the care children get at the same time.

“We’ve been talking about how childcare workers get paid worse than zookeepers since the 1980s.”

Pay has been a long-standing issue for early childhood educators, says Armine Yalnizyan, an economist and Atkinson Fellow on the Future of Workers. “We’ve been talking about how childcare workers get paid worse than zookeepers since the 1980s,” she says. “A lot of ECEs get paid the minimum wage, and that’s not even a living wage in many provinces.”

Last July, the Association of Early Childhood Educators of Ontario released a report that detailed the main issues facing ECEs. Unsurprisingly, pay was at the top of the list. “While childcare is unaffordable for many families, the daily cost of childcare operation is also artificially low because educators are underpaid,” the report reads. “In essence, educators’ low wages currently subsidize the cost of care.”

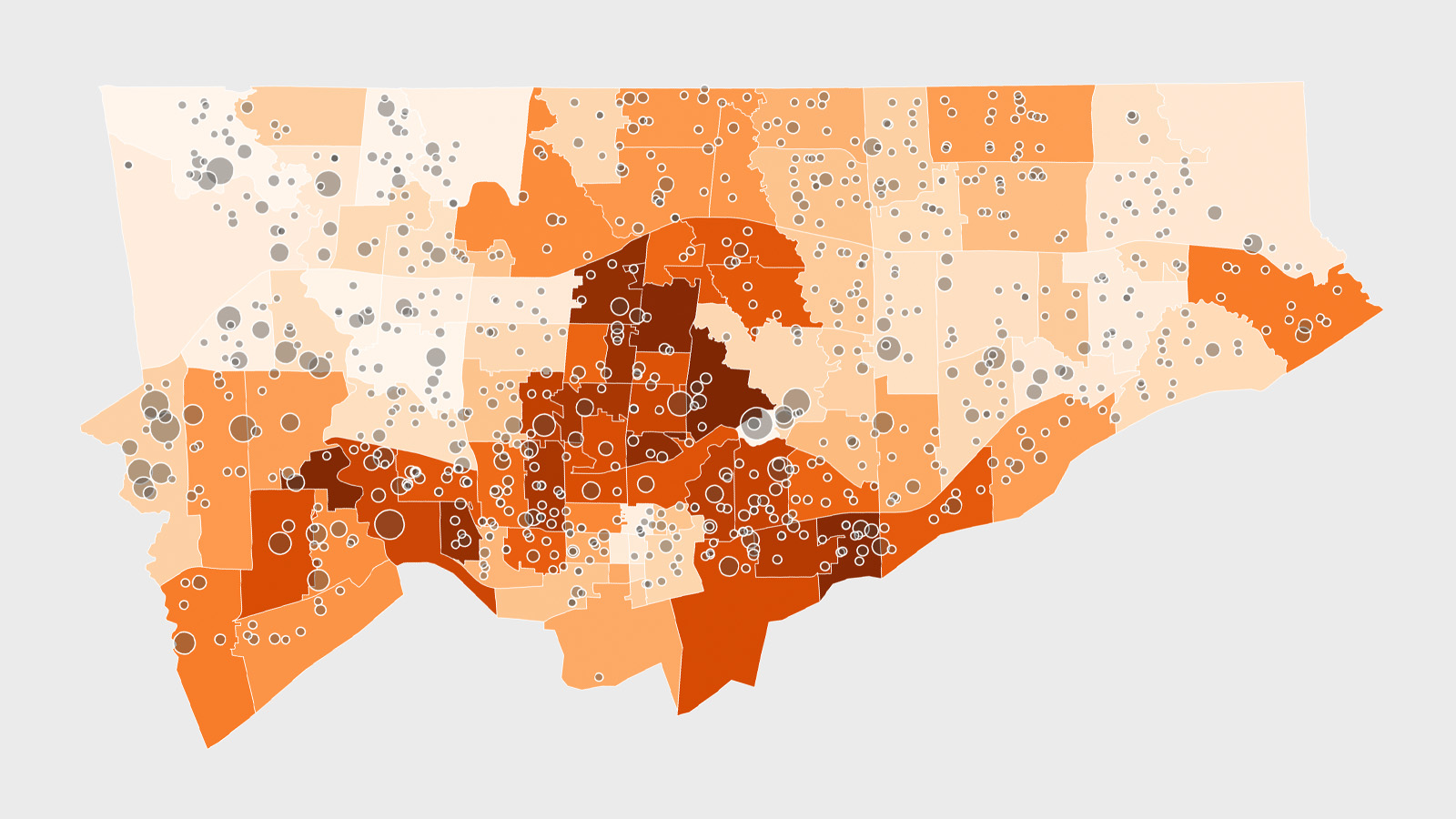

That may seem counterintuitive to families who are paying more for childcare than their mortgage. According to a recent report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the average Canadian family paid $955 a month for infant care in 2020, while families in Toronto paid $1,866.

That’s because childcare is treated as a market-based system. But it doesn’t function well that way, for workers or for families, says Brooke Richardson, president of the Association of Early Childhood Educators Ontario. The laws of supply and demand break down when it comes to caring for children. “You can’t return your childcare like you return a scarf. You can’t ask for a refund or go to the next childcare centre, because you don’t have any options,” says Richardson. “And a market-based system is not conducive to things like decent wages and working conditions.” Funding that happens through the government, instead, would allow both parents to pay less and workers to make more.

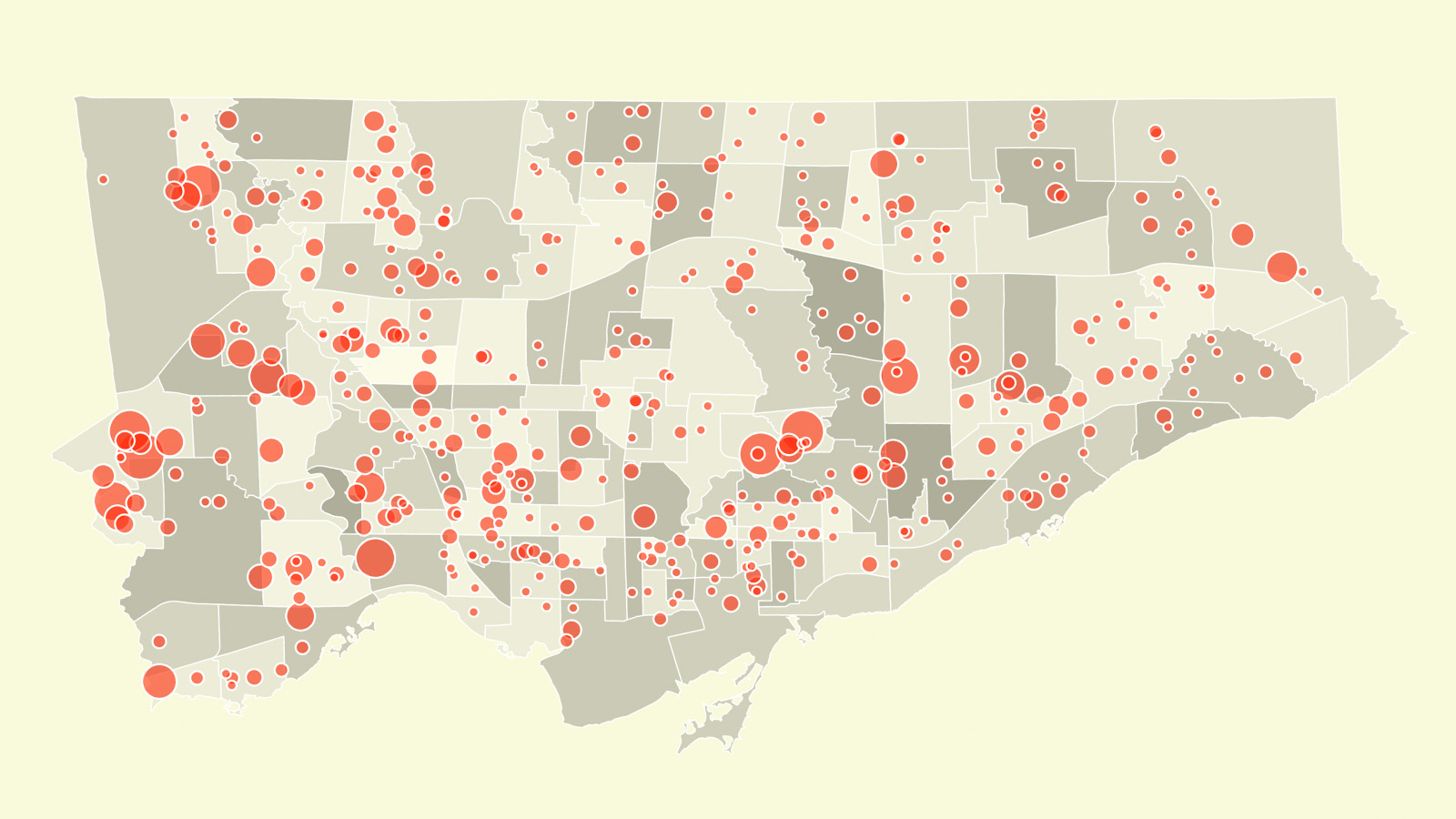

The current situation has led to a retention and recruitment crisis: registration into the College of Early Childhood Educators has been declining about 7 percent a year, and the average registered ECE working in licensed childcare in Ontario only keeps their membership active for three years. According to the latest statistics, from 2016, 96 percent of ECEs are women, and 40 percent are racialized. And these women are leaving the industry in droves.

The industry has had a retention issue for decades, making it difficult to hire and keep staff. “We’re seeing the mass flight of ECEs, and this constant turnover is a huge problem,” says Richardson. The fact that many students in ECE programs instead choose to move to teaching or other careers shows that many do want to work with kids, and would be ECEs if the jobs were better.

Anisha Grossett, an ex-ECE turned childcare consultant, says these are common concerns. “ECEs are really putting themselves out there for families, and knowing that you can go home and not worry about paying your bills is hugely important,” she says. “A lot of the professionals I worked with did have to have a second job, and it’s hard to have the energy to pick up a night job.”

Grossett has seen a lot of ECEs quit. And that staffing shortage leads to stress and burnout for those who stay. Taking time off, for example, becomes difficult when a centre is understaffed. “Because so many people are leaving, the ones that do stay, they’re being pulled in many different directions,” she explains.

As the federal government pushes forward with its $10-a-day childcare initiative, there is hope that change is coming. “The federal government was urged to say you cannot improve childcare, and you can’t even attract enough workers to expand the system, if you don’t do something about wages and working conditions,” says Yalnizyan.

The Ontario Coalition for Better Child Care has put forth recommendations that it would like to see in a new childcare deal that include a $25 an hour starting wage that increases on a grid, and paid planning time, paid sick days, paid time for professional learning, and commitments to anti-racism and Truth and Reconciliation training.

But, because childcare is a bilateral agreement, the feds alone can’t make any of that happen. And only half of the provinces who have signed on to $10-a-day childcare mention wages and working conditions at all in their agreements.

Yalnizyan worries that the Ontario government might not be on board. “This government tends to downplay the value of these workers,” she explains.

Changing childcare funding without addressing ECE’s needs, Richardson says, would be a huge missed opportunity. Yalnizyan points to Quebec’s decades-old childcare system, which offers parents care for $8.50 a day, as a warning about solely focusing on the number of spots available. Concerns around childcare in the province are so widespread that Premier Legault campaigned on improving the quality of care when he ran for leadership. “If you just focus on quantity, and not on quality, then yeah, you get more mommies working, but you reduce the quality of care for the next generation,” says Richardson.

The laws of supply and demand break down when it comes to caring for children.

From her job as an ECE, Charlene worked her way up to become a director, getting a bump in salary along with the more senior role. “I believe the lowest paid position was around $19 an hour, and I made $29,” she says.

It was enough, and yet not enough at the same time. She was able to pay her half of the bills, but worried about what would happen if she lost her cheap apartment. She wondered if she’d ever be able to take a vacation. Sutherland says staff at her centre used their own money to pay for the supplies. “One year I had 39 kindergarteners, and they said, ‘Here’s $100 for half the year,’” she remembers. Over her career, she estimates she’s spent thousands of dollars on basic supplies for her kids.

The fact that the centre scrimped on paid prep time and supply budgets made her upset. And staffing shortages meant additional issues. As director, she wasn’t supposed to work in a classroom, but frequently did when someone was sick to ensure they were within the legally required ratio of students to staff.

It all started to add up. She began to feel disrespected at work—and outside of it, too. She read comments online that referred to ECEs as glorified babysitters. She had a parent scream in her face after she reprimanded them for being late to pick up their kid. “At some point you have to say, this isn’t right,” she says.

This month, daycare workers were once again asked to provide essential care and put themselves at risk of contracting COVID. Even as schools closed, daycares have remained open, and providers are working with many kids too young to be vaccinated or even masked. For two years, COVID has added a different kind of pressure to ECEs, as they’ve been forced to take on additional risk, and do additional cleaning and screening. Some staff risked infection even as most other businesses were closed; others were laid off as centres closed and worried parents chose to temporarily pull their kids out of care.

The pandemic, however, did have a silver lining: it highlighted the importance of childcare. “That labour, and the value of that work, became impossible to ignore,” says Richardson. Parents who in the past may have just dropped their kids off at daycare and not thought much more about it were, in lockdown, stuck taking care of their children at home.

As women began dropping out of the workforce and discussions of a resulting “she-cession” hit the news, the economic importance of childcare also became top of mind. Richardson believes that means the public can now see the value of ECEs—even though, she points out, that hasn’t translated to increased pay or even vaccine prioritization.

For Sutherland, the pandemic mostly brought time to reflect. “COVID was a big turning point for me,” she says. “Being able to stop made me go, ‘You know what, I’m just miserable. I don’t feel like this career is respected, it’s not taking me anywhere, and I need to get out.’ I felt like I was worth more than what this company was giving me, and I deserved more.”

Then, she got an email that said the company had applied for wage subsidies for head office staff, but not for ECEs. Office staff continued to be paid, while ECEs went on CERB. She was so insulted, she decided it was time to quit. “Reading that email, I realized that I was going to need to get out as quickly as possible,” she says. She started looking for other options, eventually deciding to go back to school to become a financial planner.

In some ways, it broke her heart to leave her team and the children. But in other ways, she was excited to move on. She was eager to find a new job—one that would treat her better, that paid her fairly, that felt sustainable. “I was mostly relieved,” says Sutherland.