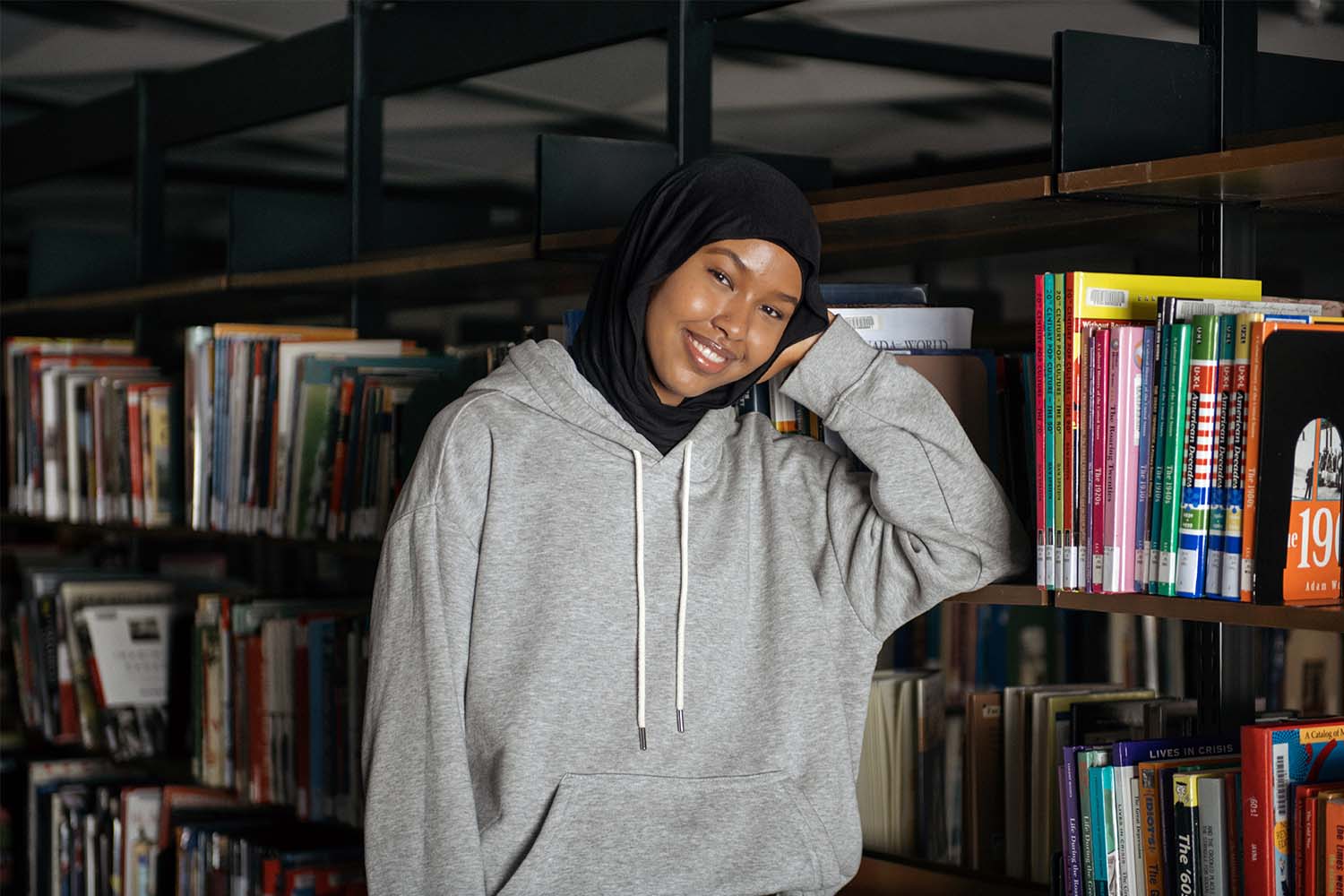

When Nasra Ali walked up the steps of York Memorial for the first time, she felt dwarfed by the imposing Gothic architecture, the school that seemed to spill on forever. It was early 2018 and she’d come with her dad to submit her application for York Memorial’s pre-AP program. At 13, Nasra had round cheeks and a soft smile, and was still wearing the crisp white-and-navy uniform of the private Islamic school she’d attended her whole life.

“Memo,” as she and her classmates would come to call it, was the biggest school she’d ever set foot inside, and it was teeming with legacy. She walked up the eleven steps that she later learned symbolized the hour, day, and month when peace was declared after the First World War. As she rounded the first corner into the hallway, she looked on as a grade 12 dance class filled the hall, a swirl of colour and sound drowning out her apprehension. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, this school is so cool,’” she says. “It reminded me of Hollywood.”

A few months later, in September, Ilhan Farah stood below a set of stained-glass windows casting rainbows across the floor of the school’s auditorium. Ilhan and Nasra hadn’t found each other yet. They were timid, among the youngest of Memo’s 900 students, and still trying on different interests for size—soccer, field hockey, basketball. Still, Ilhan drew a quiet strength from those artful windows that commemorated wartime battles in shades of blue, red and gold. These walls, she thought, held history.

On May 6, 2019, Ilhan and Nasra sat in gym class alongside their friends Esraa Idris and Jaalle Gormu when the fire alarm began to blare. Magda, Ilhan’s friend since pre-school, sprang up from the floor holding her belongings. “You can leave those here,” her teacher told her. “It’s just a drill.” She put her backpack and laptop back down and walked nonchalantly out the door.

“Grade nines are just immature,” Jaalle says. The alarm felt like an excuse to get out of class, nothing more. “We didn’t really take it seriously.” It wasn’t until the students stood lining the curb that they could smell smoke in the air. Something in the walls of the auditorium had sparked—a loose wire, an errant surge—and set the school’s legacy alight. Fire trucks began to arrive. When the students heard later that the flames were out, they felt awash with relief.

The next morning, Magda awoke to a frenzy of messages. Overnight, the fire everyone thought was out had reignited. By morning, the school’s walls were collapsing. Smoke erupted from the roof and cascaded northward across the city. Officials ran from house to house on the surrounding blocks, ordering people to leave and writing “no answer” or “okay” in chalk on the homes as they went. One student, on the sidewalk, said it felt like losing a member of their family. The principal stood watching the blaze with tears in her eyes.

It took ten hours and 150 firefighters wielding water cannons to put out the fire for good. By then, the school was decimated. The floor of the gym, where Nasra, Ilhan, Magda and Jaalle had sat the day before, was now caked with sludge, a mix of groundwater and soot. They’d left lockers filled with laptops, wallets, sweaters, memories. Everything burned.

The fire marked the beginning of four years of instability that would come to define the York Memo class of 2022. Pushed from school to school, online and off, the students have lived through unthinkable challenges amid all the usual bumpy, heartbreaking, formative experiences of high school. These girls have banded together—amid fires and plagues—to support one another and build a community. They began high school timid, trying to find their way, and have emerged from the turmoil of these formative years knowing that what they can rely on is each other, and themselves.

Two weeks after the fire, the 900 students of York Memo were told to report to George Harvey Collegiate Institute at Keele Street and Rogers Road, Memo’s longtime rival.

The Memo students dwarfed Harvey’s 500 students, and tension ripped through the building. Fights broke out between the rival factions. When Memo students struggled to find their way around, Harvey students called them refugees. Without enough classrooms, some teachers taught classes in hallways and closets. The cafeteria lunch line was too long for students to buy food. And because the TTC didn’t add more buses to the new route, it took some students more than an hour and a half to get home after school, watching bus after bus packed with students roll past.

Still, Nasra, Ilhan, Magda, Esraa and Jaalle had each other. They’d bonded first over their shared Muslim faith and then their love for Ariana Grande. Back at Memo, they had carved out space to pray when and where they could—a corner of the library, an art class, the back of that stately auditorium. At Harvey, there was nowhere to go.

The following year, the Memo students were moved to Scarlett Heights Entrepreneurial Academy in Etobicoke, a school that was shuttered two years earlier due to declining enrolment and had been sitting empty ever since. While the new location was a 40-minute bus ride away from their old school, the Memo students were thrilled to have a home again. The girls, now in grade 10, quickly grew accustomed to their new school. So in February, when the board announced it was considering moving the students again—back to George Harvey for the following school year to cut costs—they were among the hundreds of students, parents and teachers who protested.

They sent letters, drew signs, and gave emphatic interviews to reporters about how much their mental health had suffered amid all the changes. “We had to learn how to be confident in our opinions, just so that we could get what we needed to have a normal high school experience,” says Jaalle. Together, Nasra and Ilhan climbed the stage at a trustee meeting to add their voices to the throng. “No! Take us back to our school,” they urged as the trustees stared on in silence. Magda, too nervous to go up with her friends, acted as hype-woman at the back. “Facts!” she shouted whenever someone made a point, riling up the crowd. Alongside finding each other, they’d found their voices too. The trustees acquiesced, and agreed to let them return to Scarlett. Finally, they could get around to the business of just being high school students.

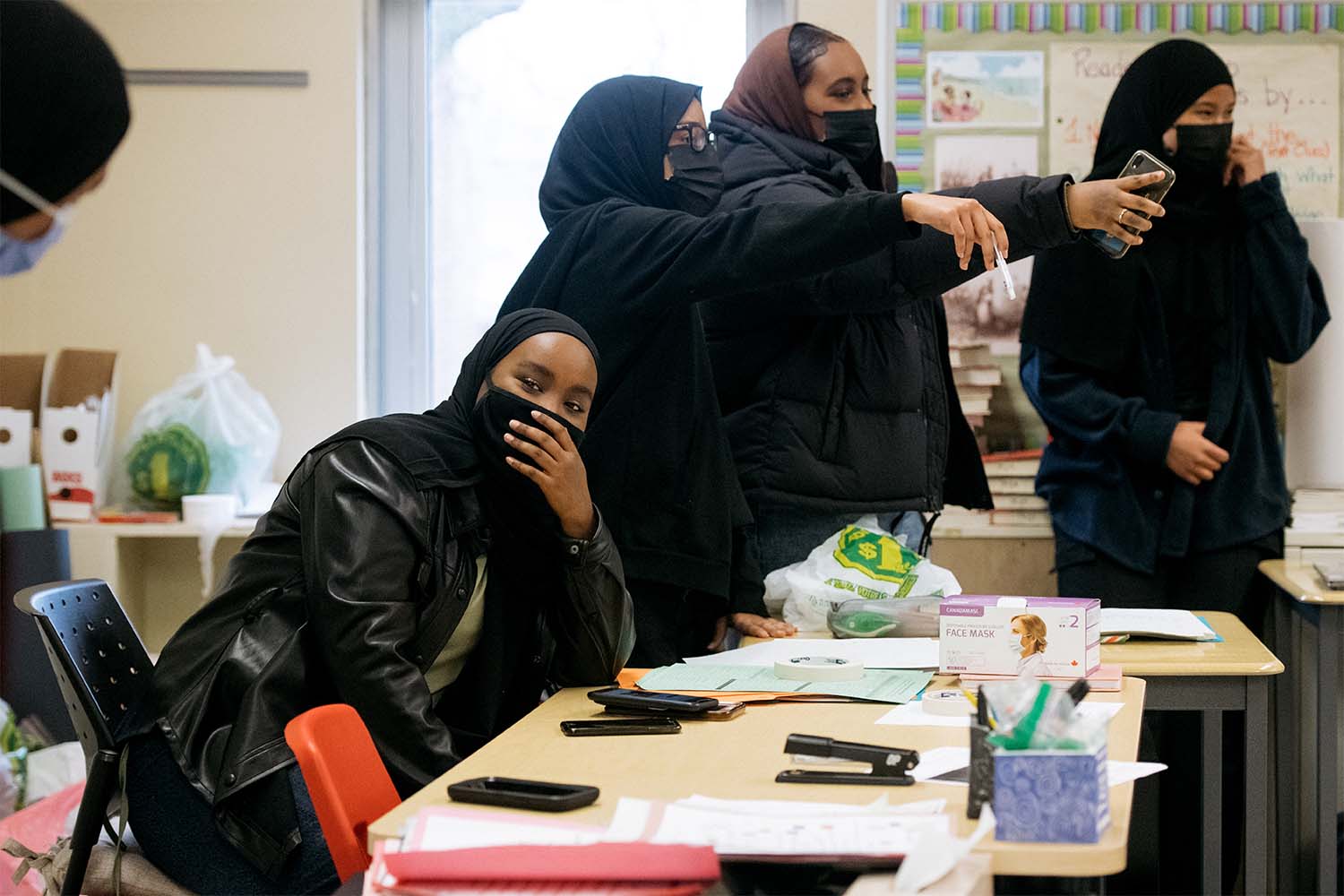

A few weeks later, Ilhan noticed some of her classmates coming to school wearing cloth masks. As February turned to March, the looming sense of uncertainty that characterized her earlier months of high school returned. Then came the announcement that students were to clean out their lockers. Then the announcement that they wouldn’t be coming back after March break. “That’s when it really hit me,” says Ilhan. “Okay, we’re probably not going to be back for the rest of the year.” She was the eldest of eight children, most of whom were in elementary school, and she’d be navigating high school online for who-knows-how-long, from a home that was bursting with energy but rarely peaceful. Magda, her friend who lived nearby, had six siblings, too. Life was suddenly both too noisy and eerily quiet. The girls were used to the festivities that often brought their Somali-Canadian community together. That spring, everything stopped. “We didn’t have school every day. It was only when the teacher was able to have class,” Magda says. “Sometimes they would upload assignments but you wouldn’t know what to do. It was like, what is this? You’re teaching yourself. It was hard.” It was a year before she was allowed to retrieve the things she’d left behind, optimistically, in her locker.

The rest of the school year and the one that followed passed in a blur, the students’ days somehow both indistinguishable and unfamiliar. Instead of gym classes, there were Zoom workouts with their teachers. Brunch plans were made, and cancelled, and made again. Nasra tested positive for COVID. Some students elected to do in-person classes, only to find that masks, empty seats and distanced desks turned a once-vibrant community into a ghost town. “I think a lot of us really lost our social abilities during those times. People I was close friends with were too shy to talk to each other, everybody was just scared to talk to each other,” Magda says. “The teacher would try to have a discussion, she’d ask a question. And everybody’s just quiet, quiet, quiet, quiet for so long. And she would just move on.” Moving on was what Magda and her weary classmates wanted, too.

When Nasra, Ilhan and Magda appeared at Amina Hussein’s door the first week of school in September 2021, they didn’t come with an idea. They came with a plan. The girls were seniors now, and utterly determined to wring as much as they could from a final year of high-school that promised, at last, to be in-person.

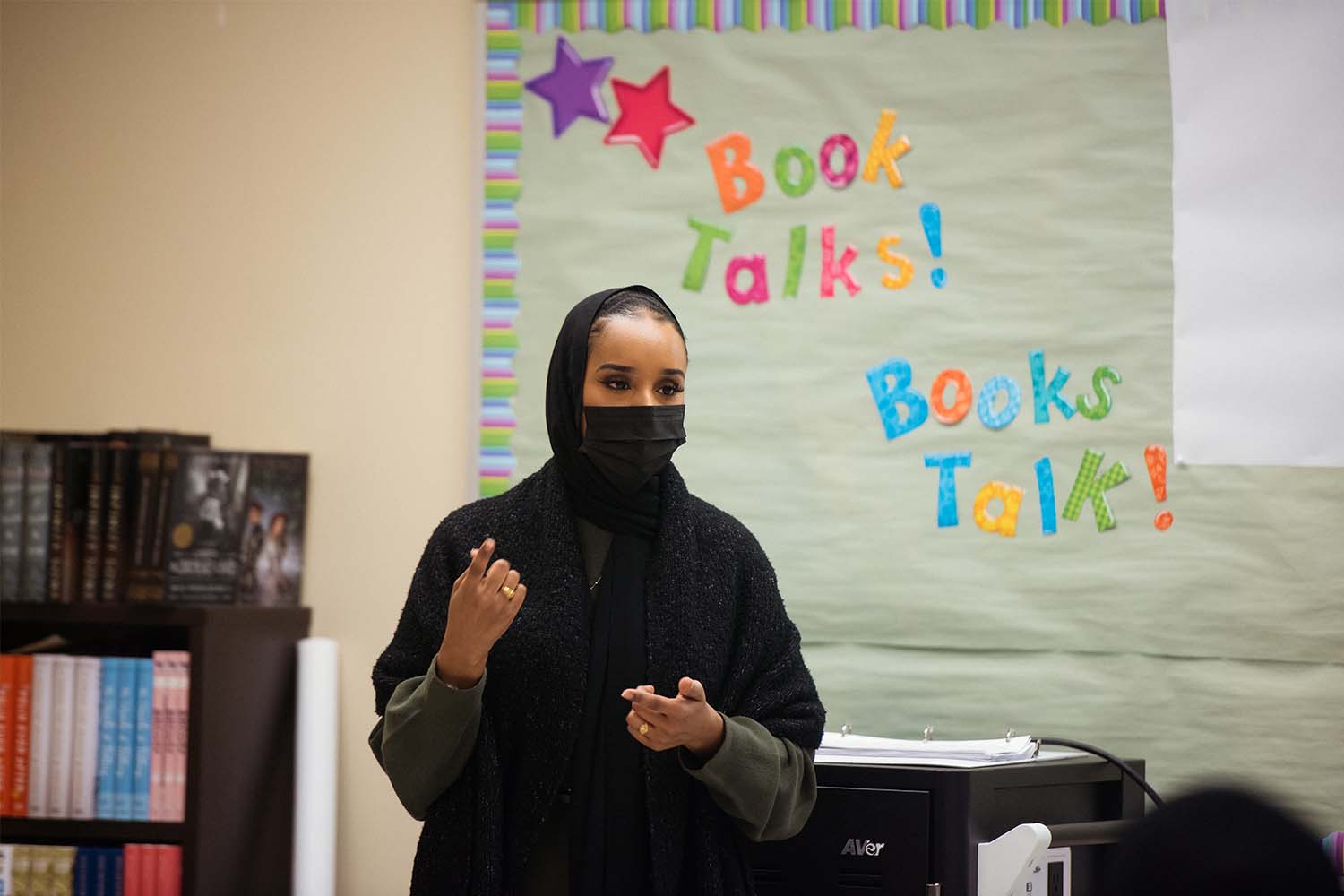

Hussein was new to Memo, teaching English and social sciences, and she wore a hijab, which made her the only visibly Muslim staff member at school. For years, the girls had talked about starting a Muslim Students’ Association. They wanted a sense of community, and to raise money for charity. Above all, they wanted to educate other students on what it meant to be Muslim.

Hussein was wary—she was trying to find her way around a new school, too, and still didn’t even know where the printers were. But the girls’ passion was undeniable, and more than a little contagious. She agreed, and the Muslim Students’ Association (MSA) was born. They mounted their logo on posterboard and proudly displayed it at the annual fall club fair, alongside the athletic association, the Black History Club, and countless other groups from what looked like most of the school’s senior class. So many students had shown up that teachers were circulating, reminding them fruitlessly to social distance. More than 100 students signed up for the MSA. “Maybe,” Hussein thought, “this is what it’s like when you have something taken away from you.”

Nasra and the rest of the executives got down to business. They sold samosas to raise money to build a mosque. They ran a clothing drive to collect donations for a local Muslim organization. They set to educating their peers, hosting game nights and meetings where they’d answer questions like, “are all Muslims Arabs?” and “are you bald under your hijab?”

The club has united them, given them a shared purpose and foundation to call their own. “I think for a lot of us, we had our fun in Grade 10, Grade 9, pre-COVID,” Ilhan says. “We were at a point where we want to wrap it up and move on to the new chapter of our lives. But with MSA now, we want to stay, we want to have more fun.” Spending her entire Grade 11 year online, Nasra says, was a complete blur, so effectively wiped from her memory that when she talks about “last year” she means 2019. “I think this year, with Grade 12, a lot of us are trying to just do as much as we can,” she says. “In a sense, we’re overcompensating. And I think everybody’s a little bit scared to move on from high school. I know I feel that way. I don’t think I’m ready to go on just yet.”

For all the uncertainty the last four years have held, the next hold even more. Nasra, who’s always been a strong student, is afraid of how she’ll handle university. Because of all the tumult of her high school years, she’s never written an exam. Ilhan and Jaalle say they’re planning to stay at home for their university years. It’s cheaper, for one, and it’s what they know.

Back at school, now, Nasra gets ready for prayer once a day, and twice during daylight savings time. She’s come a long way from when she and her friends used to find a spot in a corner of the library. Now, in a dedicated prayer room, she listens as their Imam guides her, surrounded by students of all years. She feels a flush of pride. She wants to tell them to find their voices, too, and sooner. She is thankful that she knows now when to fight. After school, she walks outside with Ilhan and Magda and Jaalle. There won’t be prom or graduation or soccer games to play, but they have each other. “Just eating with your friends and playing games and being goofy and making jokes and having fun together is just the best thing,” Jaalle says. “We don’t have to do much to enjoy ourselves.”

One morning this winter, Ilhan and Magda take the usual trip to Scarlett Heights from their neighbourhood, waiting at the stop together until the 32 Eglinton West bus groans up beside them. The route takes them past their old school building, and they begin to reminisce, pointing out the park where they ate lunch together before they got chased out by a dog, or the forest they’d explore after school—filled with nostalgia for their younger selves. “Instead of looking at the building like, ‘Oh, man, I miss it, we can’t make new memories here,’ we can look at it like, ‘Oh my god, do you remember that?” Ilhan says. Magda leans her head on Ilhan’s shoulder and smiles. They can laugh about it now.

The school’s ruddy brick turrets survived the fire, as did the two burning torches carved into stone that light the way into the school. The stained-glass windows that so captured Ilhan’s heart four years before did not. They’d been etched with the school’s motto, which in Latin reads “macte nova virtute.” The inscription is gone, and the students carry it with them instead. Translated, it means: “Go forth, with new strength.”

Editor’s Note—Jan 3 2024: a previous version of this story used one of the subjects’ full name. It has been changed because of privacy concerns.