Back in 2019, when Linda first learned of the poor vaccination rates at da Vinci School, she didn’t realize vaccines would soon become a topic discussed the world over—and a point of serious contention for some parents at the school.

Da Vinci is an alternative public school in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) near Spadina Avenue and College Street, a five-minute walk from the University of Toronto. In 2019, the school had just 85 students, from junior kindergarten to grade six. It also had the highest rate of non-medical exemption to existing mandatory vaccines for public school children, with 36 percent of its student body exempted from the DPT (diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus) and MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccines—six of nine mandatory vaccines in Ontario, and the only vaccines for which Toronto Public Health (TPH) releases school-level exemption data.

For Linda (who is using a pseudonym out of fear of reprisal), navigating conversations about the low rates of immunization at the school “was awkward, and weird.” She was still finding her footing in the school community, and didn’t know exactly what to think. Like many other parents and teachers, she was surprised that vaccine hesitancy was such a significant problem, but it didn’t yet feel like an imminent threat.

“We didn’t know that light anti-vaxxing was about to become a global issue,” she says. “But my gut was telling me [something] was off.”

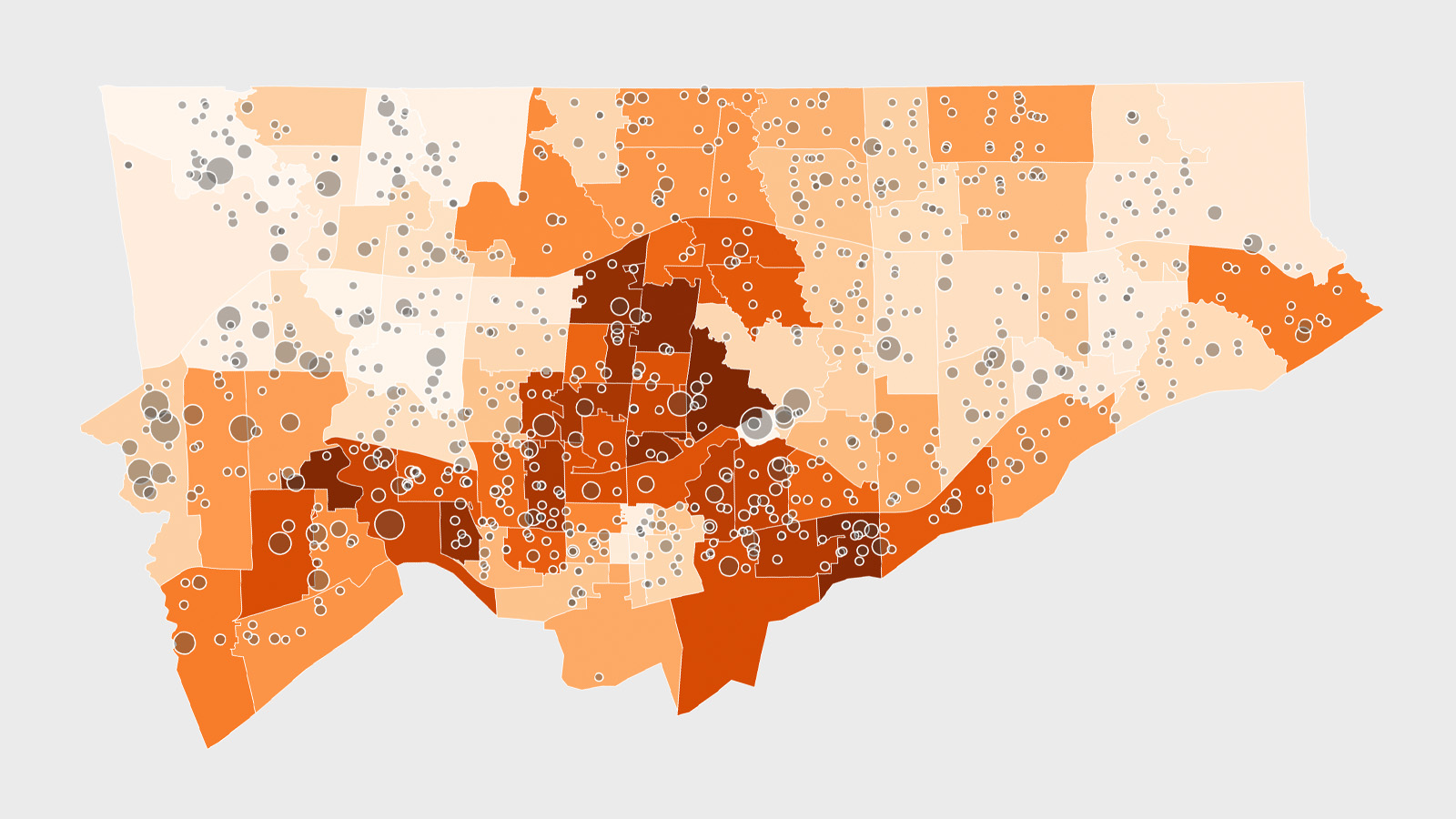

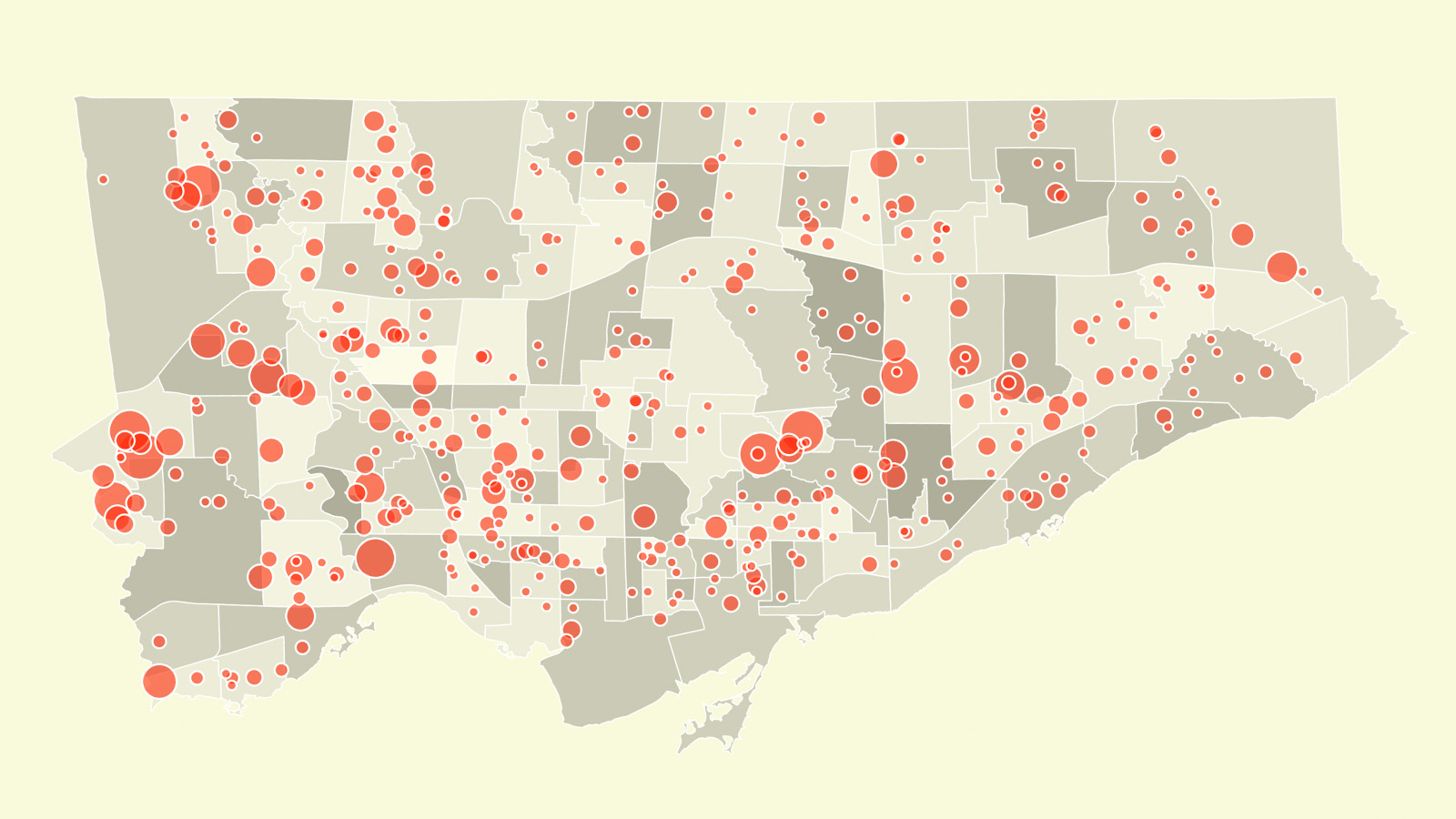

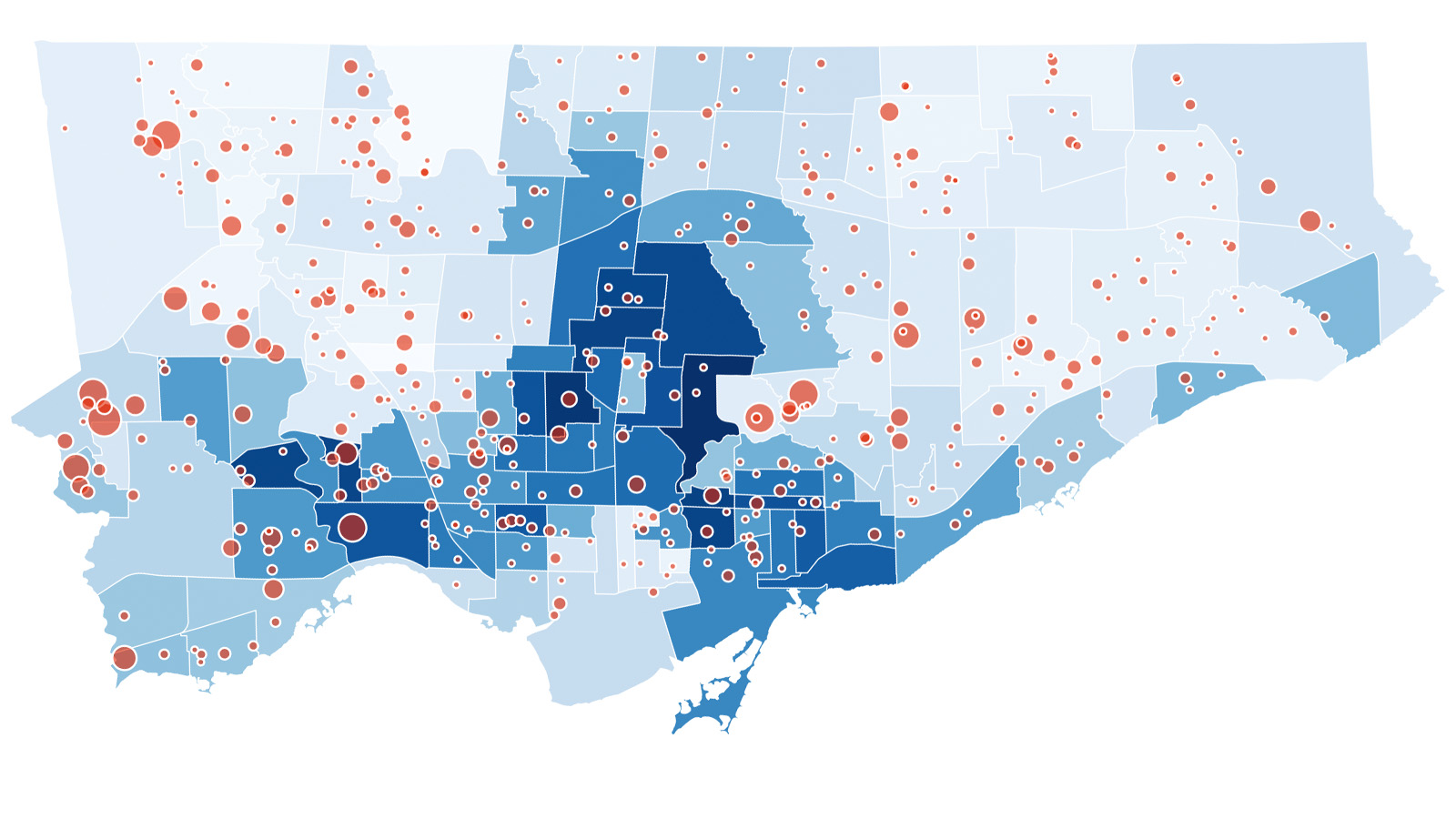

The problem of vaccine hesitancy isn’t unique to da Vinci. Analysis of TPH’s 2018/19 school year data by The Local has found that alternative elementary schools in Toronto have a 13 percent rate of non-medical exemption to mandatory vaccines—more than seven times higher than the 1.8 percent at mainstream schools. Now, with the rollout of the COVID vaccine for children age 5-11, the conversation in alternative school communities has taken on a new urgency. Opportunities for misinformation are rife. Conflicts have broken out between parents who are masked and unmasked, vaccinated and unvaccinated. And the history of low vaccine uptake across these schools has raised the question of whether there’s something endemic to alternative school culture that makes them the site of such hesitancy—and what parents, staff, and the school boards can do to address it.

When COVID first struck, some parents and teachers at da Vinci began to wonder whether vaccine hesitancy at the school would inform their fellow community members’ views on the pandemic.

“I did come up against some real anti-science rhetoric last year,” says Linda. In her experience, there were just a handful of parents pushing unscientific theories about COVID, but they were very vocal with anyone they felt would listen.

Linda recounts one occasion on which a parent expressed the belief that the pandemic wasn’t a threat to children because they simply couldn’t catch the virus, adding that asymptomatic transmission didn’t exist. This is, of course, incorrect: children make up nearly 13 percent of Ontario’s COVID cases, and there is scientific consensus on the existence of asymptomatic infection and transmission.

On another occasion, an argument broke out at daycare pick-up between a da Vinci parent and a parent from Lord Lansdowne, the larger school inside which da Vinci is sited. When the Lord Lansdowne parent noted that the da Vinci parent and their child were unmasked, a heated disagreement resulted in which the da Vinci parent claimed, loudly, that COVID was no worse than the flu (the incident was confirmed to The Local by staff at the daycare).

“They believe COVID to not be real,” Linda says, adding that these particular parents were more concerned about the impacts they felt mask-wearing would have on their children.

The da Vinci community is not a monolith. Parents come from different disciplines and professions, from the performing arts to public health and medicine. Some parents and teachers say they’ve never witnessed extreme views on vaccines or the pandemic. But others say a strong streak of anti-vaccine sentiment does exist, and that the parents who express it have one thing in common: an avid commitment to the da Vinci school’s foundational approach, the Waldorf learning philosophy.

Waldorf learning was created in the 1920s by Austrian philosopher Rudolph Steiner. Today many of his theories—which included bigoted anti-Black racial essentialism and a belief in clairvoyance—are no longer a part of the Waldorf approach to teaching. Instead, Waldorf schools primarily focus on immersing young children in arts, nature and movement-based learning, and avoiding technology where possible.

While this pedagogy seems harmless, Waldorf schools in wealthier, white liberal enclaves in New York, California, and even in Europe have become bastions of growing anti-vaccine sentiment. This could be because the values of some parents or administrators reflect Steiner’s own beliefs on childhood illness, which were skeptical of modern medicine and proposed that childhood illness is necessary to help children grow stronger, both physically and mentally. (Waldorf organizations in both North America and Europe have publicly distanced themselves from anti-vaccination sentiment.)

Da Vinci is in the delicate position of being a Waldorf-inspired public school, meaning that it can only espouse those Waldorf philosophies that align with the TDSB’s and province’s ethics and principles. According to its website, the school is inspired by “the ideas and ethical principles of the Waldorf approach to learning.”

In practice, this isn’t always easy. Between 2017 and 2019, the parent’s council at da Vinci brought in a Waldorf mentor meant to educate parents and teachers on Waldorf approaches to education. Jane (who is also using a pseudonym to protect her identity) described the education as going a step too far.

“She most definitely brought her anti-vaccination ideas with her,” Jane says, recalling that the mentor argued that vaccines aren’t necessary because “the belief within Waldorf is that childhood illness develops the child’s fortitude.”

The fact of the matter is, the majority of da Vinci parents don’t buy into this philosophy, and are not anti-vaccine—and those who are inclined towards hesitancy don’t often veer into conspiracy theories and right-wing talking points. Most parents have enrolled their children in the school because they appreciate the small class sizes, the focus on arts and the outdoors, and because they themselves went to alternative schools as children. The community members The Local heard from added that the school community’s conversations on vaccination haven’t been particularly open or extensive so far—parents tend to talk with those they know, and don’t share their opinions with each other unsolicited.

But in an environment that has already become more isolated by the pandemic, and with parents not getting to encounter each other in school settings as often, the result is that parents most often hear from like-minded counterparts whose views they already agree with, creating silos where a small number of anti-vaccine parents speak primarily with each other and with school staff. And the existence of these parents begs the question of whether they might be indicative of a pattern in alternative schooling.

“The belief within Waldorf is that childhood illness develops the child’s fortitude”

Umair Majid, a PhD candidate from the University of Toronto, has been studying vaccine hesitancy among parents since before the pandemic began. One of the factors he found influenced parents’ vaccine hesitancy was a commitment to “natural” or “organic” living, which the parents felt was incompatible with biomedicine, and therefore vaccines. This isn’t always the case—natural living isn’t inherently anti-vaccine, Majid emphasizes—and some parents do go in the other direction. One parent from Toronto alternative school The Grove said that her interest in nature helped her understand COVID as being inherently tied to the climate crisis, a relationship that is still being studied as the pandemic continues.

The parents who feel natural living is incompatible with vaccinations, Majid’s research indicates, are often white, affluent, and well-educated—the same demographics that researchers say are also more inclined to place their children into alternative schooling. A 2017 review of alternative schools in the TDSB found that elementary school students from middle and higher income families were overrepresented. While race-based data was not collected, the report also noted a lack of diversity among younger students.

But more than identity, the decisions vaccine hesitant parents make are often guided by the networks around them. “They have their own communities where they exchange information, even look at peer reviewed articles, question them on their own,” Majid says.

If parents are closer to the middle ground, it’s easier to convey information to them through public health sources; the farther they move to extremes, the more they distrust sources outside of their networks.

Megan Fehlberg, a parent at da Vinci, has always occupied that middle ground. “I’m a questioner,” she explains. “I believe in science, I want to trust science, but I also really want to do good research. And I don’t jump in with both feet.”

It’s an outlook that has informed both her health-care decisions—her children have received some vaccines, but not others—and, perhaps unconsciously, her decision to enroll her children at da Vinci, a school that defies mainstream approaches to learning.

Fehlberg’s initial hesitation with the COVID vaccine was informed primarily by her criticism of pharmaceutical companies, and the influence of “billions upon billions of dollars, and the effect that has on the scientific process. If it was just scientists, and there was no concern about profit, I would have no hesitation,” she says. This was complemented by a belief that COVID is not as much of a danger to children as it is to adults.

Fehlberg sought out more information with her pediatrician, but didn’t get much insight from the experience. Ultimately, it was her next-door neighbour, a microbiologist, who explained the science of mRNA vaccines to her—something she and many others across the world previously thought was a very new technology.

If she hadn’t gotten the opportunity to speak to her neighbour, Fehlberg admits she’d probably still be hesitant and scared. Now, she says, she wants her kids to get the vaccine immediately. But she also recognizes most parents don’t have access to scientists next door, and that there’s a risk involved in relying on this interpersonal information-sharing.

“People form communities,” she says. “They reinforce each other, and then you go and you look for information that reinforces this belief. […] There’s all kinds of opportunities for sharing misinformation.”

The values that inform a parent’s decision on where to enrol their child feel inextricable from the values that inform their attitude towards vaccines.

The Africentric Alternative School in York University Heights is Canada’s only school focusing primarily on the perspectives and histories of Black and African people and communities, and was created to meet the needs of Black students marginalized by the mainstream education system. There, conversations on COVID vaccines for students are only just beginning. In prior years, the school has had one of the highest levels of exemption from mandatory vaccines of all the schools in the TDSB. During the 2018-19 school year, for example, 21 percent of students at the school were exempt from DTP and MMR vaccines for philosophical or religious reasons. Needless to say, the parents’ conversations and decisions are informed by a set of concerns and experiences vastly different from whiter alternative schools in the city.

The trauma imposed by the medical system on Black communities, both historically and in the form of systemic everyday racism, has fostered a vaccine hesitancy that plays into many Black peoples’ medical decision making, says Jelani Philbert, a parent at the Africentric school. “It would be ludicrous to say that Black people don’t have that idea somewhere in their mind.”

“Whether or not it’s an active contributor to the decision is another conversation,” he adds, emphasizing that every parent weighs the factors differently.

Philbert and his child’s co-parents are still deciding whether they’d like to give their child the COVID vaccine—but the decision-making process doesn’t seem as isolating as it might be in other parent communities.

Of course, everyone in the Africentric parent community isn’t going to be on the same page, he says. “[But there’s] more of a communal conversation and a space where folks can come in, have informal and formal spaces to be able to discuss their concerns, their feelings, their thoughts.”

“From the time that I’ve been sending my son to the school, that’s the main difference [I’ve seen] between this and all of the other school systems and options.”

Just a few weeks ago, parents were invited to an information session hosted by the Black scientists’ task force, the latest in an extensive outreach effort by the group to address the concerns of Black, African and Caribbean Torontonians with regards to COVID and vaccinations. When approached for comment, the TDSB and TPH said there were no similar plans to provide targeted outreach and vaccine information to parents at other alternative schools with high rates of exemption from mandatory vaccines.

The values that inform a parent’s decision on where to enrol their child feel inextricable from the values that inform their attitude towards vaccines.

Vaccine-hesitant parents are part of the reason vaccine exemption regulations exist in the first place, says medical historian Heather MacDougall. Vaccinations only became mandatory for school-age children in Ontario in 1982, after years of pressure from health groups like the Canadian Pediatric Society and the National Advisory Committee on Immunization, and following disease elimination campaigns in the U.S. Prior to the legal framework, now known as the Immunization of School Pupils Act, roughly 25 percent of children in Ontario hadn’t been immunized to basic diseases.

But the Act elicited vocal opposition from a small number of parents’ groups, like the Committee Against Compulsory Vaccination, whose protests contributed in part to the introduction of the non-medical, “conscientious” exemption regulations we see today (religious exemptions were already included in the Act). The other major factor in allowing philosophical exemptions, MacDougall explains, was an attempt to avoid violating the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. As a result, parents could apply for exemption without really having to justify their ideological stances.

It was only in 2017 that the province implemented education sessions for all parents asking for non-medical exemptions. The sessions are provided by the parent’s local health unit, either in groups or individually, after which the parent has to watch a 30-minute video on vaccines. But in a 2018 survey of parents going through the exemption process, nearly 80 percent said they still intended to seek an exemption for their child after attending a session, according to TPH.

In 2019, in response to the fact that non-medical exemptions had more than doubled in little over a decade, TPH requested that the province end the use of non-medical exemptions for existing mandatory vaccines. The province declined to make any changes.

This September, in preparation for the rollout of COVID vaccines to children, TPH and the TDSB requested that the provincial government add the COVID vaccine to the existing list of mandatory immunizations. The province once again declined.

For many public health experts, this feels like a mistake. Onil Bhattacharyya is a parent of two da Vinci students and a clinician scientist with Women’s College Hospital and the University of Toronto. Two years ago, when he first heard about low vaccination rates at his children’s school, he considered holding information sessions at da Vinci. When the pandemic began, he decided it was time.

During the pandemic, Bhattacharyya has held Zoom sessions, one for each of his children’s classes. He’s taught kids how vaccines help increase life expectancy and eliminate disease, and explained the benefits of COVID vaccines as a public good. Bhattacharyya was impressed by the response—the children had a strong grasp of the science behind vaccines for their age.

But with adults, it’s not that easy, he says. To some degree, their beliefs have already been cemented; often, it just comes down to the openness and approachability of educators and parents.

“People are not going to understand the ins and outs of the science and all the trials and everything,” says Bhattacharyya. “They either like me and believe me, or they don’t.”

As both a public health professional and a parent, Bhattacharyya sees the risk of siloing in communities like da Vinci, and recognizes how parents can sometimes be driven further into their beliefs. But perhaps counterintuitively (to those outside the world of public health), he points out that vaccine mandates could be the solution to pull parents out of their silos.

“Vaccination, from day one, has had resistance, right? I don’t know that you’re gonna change everyone. [Some] strategies are not about convincing them, they’re just about framing the choices they have.”

Fundamentally, it’s about changing the risk-benefit analysis. To a vaccine-hesitant person, the benefits of being vaccinated aren’t convincing. What is convincing is the knowledge that refusing the vaccine means giving up on social experiences—restaurants, entertainment, social engagements, even the company of loved ones. Over time, those losses prove to be a greater cost to their lives than any potential risk posed by vaccines, which have been proven minimal, at most, by scientists worldwide. Simultaneously, as more children and adults receive the vaccine, its efficacy and benefits will become apparent, and parents’ worst fears will be assuaged. The hope is that with time, this will break down the silos that parents have built for themselves.

“My sense is those extreme views will become more marginal over time,” Bhattacharyya says.

The hope is that the province ultimately recognizes the value of a vaccine mandate—but that feels like a remote possibility, at this stage.

Until then, the responsibility lies with fellow parents, school staff, school boards and public health units to reach vaccine-hesitant parents. It starts with meeting them where they are, ideologically. You have to assess parents’ concerns in a neutral manner, no matter how outlandish they are, Bhattacharyya says; then, once rapport has been established, convey the importance or efficacy of vaccines in a way that addresses those concerns, all the while trying not to be paternalistic.

“There’s a kind of moral framing that I feel is challenging, but I really think it’s at the core of this: how much does public good matter to you?” he says.

Bhattacharyya sees a point in the future when parents’ fears will be replaced by a recognition that the vaccine has proved effective, safe, and worth buying into. “We can get [there], but it takes us all to do it together.”