The first time Adam Chaleff filed a compliance audit, it was his word against that of the newly elected mayor of Canada’s largest city. Under the cold, clinical lighting of Committee Room 1 in City Hall, all eyes were on the then 26-year-old as he tried to convince Toronto’s three-piece compliance audit committee—the municipality’s primary arbiters of campaign finance accountability—that Rob Ford had overspent his spending limit by nearly $100,000 and that his 2010 campaign required a forensic audit.

Nervous wasn’t quite the word for how he felt. Chaleff was perfectly composed on the outside, measured and well-spoken as always, though he admits that making the case that the sitting Mayor cheated and shouldn’t hold office anymore will “get you going.” Chaleff summarized his case—an investigation that started as a curious look into Ford’s campaign expense sheet and ended as a 17-page submission citing the Municipal Elections Act, compiled with the help of his friend Max Reed, then a fresh law school graduate. To their surprise, Ford’s lawyer didn’t present much material countering their accusations. The audit was ordered.

In 2010, Chaleff was no stranger to politics. He’d grown up protesting Mike Harris’ cuts to public education, worked on campaigns, sat on a mayor’s roundtable, and was working as a labour relations specialist for AMAPCEO, an Ontario trade union representing public servants. He’s unabashedly left wing. A 2003 NOW magazine profile named teen activist Chaleff as “the Tory Toppler.” He’s been called “a little snake” by Doug Ford, and was even confronted by him in a City Hall hallway in 2011. The way Chaleff sees it, though, campaign finance accountability is an inherently progressive issue. “We’re trying to create a level playing field that makes it possible for progressives who don’t have access to big money and powerful interests, to be able to run campaigns,” he says. A compliance audit was, for Chaleff, simply a new tool in this fight.

The compliance audit system is the only accountability measure Ontario municipalities have to ensure their elections are fair, that candidate expenses are above board, and that local democracy is working as intended. Any citizen can request one, candidates included, for politicians they believe violated the election finance rules, as long as they have “reasonable grounds.” Applications and documents are submitted via email in the summer after the election. At a hearing, applicants and candidates then have a chance to make their arguments in front of a committee chosen by a panel of citizen experts appointed by city council. The committee considers the application and decides whether or not to initiate a forensic audit.

It’s a curious system. We imagine elections as being like soccer games–refereed contests, with everyone playing by the same rules. In reality, they’re soccer games in which the referee doesn’t enforce the rules until years after the game is over, and only if a fan asks for an audit of a particular slide tackle. Often, even when the referee finds a player has committed an infraction, there are no consequences.

That’s what happened two years after Chaleff’s application against Ford was granted. In 2013, the audit report came back: Ford’s campaign had violated the Municipal Elections Act in about 100 ways, from miscategorized fundraising events to premature campaign expenses to illegal loans from his family’s company, Deco Labels. He had overspent his $1.3 million spending limit by $40,168. Nonetheless, the compliance audit committee decided not to commence legal proceedings against Ford. At the time, the rules didn’t say they needed to provide a reason, either.

In the decade since, Chaleff has been involved in about a dozen compliance audit requests. In his experience, the official system to monitor local politicians is fundamentally flawed. He says when election accountability takes years to carry out, the damage is already done. “You can’t put the toothpaste of an election back in the bottle,” he says. While the Municipal Elections Act outlines legitimate penalties for overspending limits, Chaleff says there’s a lack of action when it comes to enforcing them. “If you’re not serious about the spending limits, they become a suggestion. Then, the sky’s the limit; how far do we let this go?”

Chaleff is part of a small group of muckrakers, policy nerds, political opponents, and activists who’ve made it their business to keep an eye on candidate spending. The people who use the compliance audit system are people who have the time, resources, and know-how to navigate this ad hoc accountability process. And like Chaleff, they’re also unsatisfied with the citizen-based complaint system, raising issues of accessibility, efficiency, and stringency. More fundamentally, they question whether election accountability should even be left up to everyday Toronto citizens who happen to take the time to scrutinize a politician’s campaign. “I call it the honour system,” says Chaleff. “If you don’t follow the rules, the only person who may look into it is your opponent or some goody-two-shoes.”

As in any other realm of politics, money is at the core of municipal elections. “In a place like Toronto, you need to have a significant amount of money in order to run for office,” says David Siegel, a professor emeritus of political science at Brock University. “Some people can raise that money better than others.” Because there’s no party system on the local level, money makes all the difference. Without well-known party platforms to lean on, it’s a game of name recognition — who will voters remember when they stare down at their ballot?

In the 60s, the decade before former city councillor Howard Moscoe was elected, the city of North York was the wild west in terms of campaign financing. A phone call to a builder could bring you a truckload of stakes for your election signs. A Toronto lawyer would collect money from developers and show up at candidates’ offices to ask how much they wanted. Former North York Alderman Irving Chapley once bragged he had enough money left over after an election to buy a new Lincoln Continental, Moscoe says.

“Anybody could accept contributions from anyone, it was all under the table,” Moscoe says. “The entire system was rife with corruption, top to bottom, in every municipality.”

When Moscoe was elected to the North York City Council in 1978, he wanted to be part of a municipal government that was honest, straightforward, and clean. In 1984, after changes to the provincial election finance system, he was approached by Bernard Nayman, a North York chartered accountant and the appointed auditor for every NDP riding in the province. Nayman wanted to bring the provincial system down to the municipal level and he wanted Moscoe’s help. “Well, let’s take a crack at it,” Moscoe told him.

Together, they proposed a sweeping electoral reform package—changes that almost all ended up being impossible to legislate, due to limits on municipal power. The only part that was adopted was a clause that forced candidates to disclose any contributions over $100. But in the 1985 election, the first time candidates were required to file their expenses, it quickly became clear that the city didn’t have the mechanisms to enforce the new rules: 27 of 64 candidates failed to file returns. In later years, the Bob Rae provincial government took the system put forth in North York and built it into the Municipal Elections Act, birthing the compliance audit system and creating accountability measures that were ostensibly more enforceable.

“The idea was to make it easier for people who felt a candidate had done something wrong,” Siegel says. “They could then go to an official body and raise that issue without having to go to a court at a significant expense.”

Compared to other provinces, Ontario actually has fairly elaborate municipal finance legislation, according to Zack Taylor, a professor of political science at Western University. He notes that in some provinces, like New Brunswick, there aren’t any rules at all. But unlike in BC and Quebec, where the province collects and makes local campaign disclosure information available, Ontario leaves the task up to its municipalities. And by nature, relying on a citizen complaint system means things can fall through the cracks. “Because it’s complaint-driven, we don’t know the things that aren’t complained about, and there’s really no way to ever know as long as the system is structured the way it is,” Taylor says.

Moscoe seems to be satisfied with these odds. He filed two compliance audit requests in 2011, for candidates Gus Cusimano and Peter Li Preti, partly because he believed they had contravened the act, and partly to protect the integrity of the system he’d help build. An audit was ordered for both, but Cusimano was only required to pay a $1,000 fine, whereas Li Preti faced charges. “I didn’t agree with their decision on Cusimano but so what? They didn’t agree with my interpretation. For Li Preti, they did,” he says. “I think people can sleep at night knowing their municipal government is functioning reasonably well.”

“The act is not perfect, but it started out a lot less perfect.”

Other Torontonians who’ve used the compliance audit system have found it to be far from perfect. Roger Brook—a Montessori teacher and former freelance journalist who has volunteered for around 10 political campaigns—is one of them.

During the 2010 election, Brook worked on Kevin Beaulieu’s campaign, a candidate running in Davenport. During the campaign, Brook and a few other Beaulieu workers became skeptical of some campaign expenses from their opponent, Ana Bailão. A colleague offhandedly mentioned that a compliance audit might be a way to look into what was going on. “But when the election was over, everybody kind of said: ‘Well that’s it. There’s no point,’” Brook remembers.

Brook didn’t give up. He started combing through Bailão’s finances after a voluntary pre-release of contributions following a candidate debate. Fourteen contributors stuck out to him: They weren’t located in the riding, they were in public housing and apartment complexes, so presumably not wealthy like many other donors, and 12 of them had donated a uniform amount of $300. He jumped on his bike to investigate, spending three weeks biking from his home in Davenport to East York and Etobicoke.

Brook’s application for a compliance audit against Bailão, submitted in June 2011, laid out his allegations. After visiting the homes of six contributors, he wrote, he found what he believed to be organized donations on behalf of the taxi company, Co-op Cabs. Brook says he took a tape recorder to visit the donors, “finding out one by one that they drove cabs for Co-op and didn’t seem to be familiar with [Bailão] or her policies.” Co-op Cabs, Brook claimed, had been “pressuring employees to donate their money on behalf of the company.”

Knowing corporate donations were banned as per the Municipal Elections Act, Brook detailed his accusations, along with what he believed to be seven other issues, and submitted his application against Bailão.

On the day of his hearing, Brook says the committee asked him for the numeric parts of the legislation he thought were being broken and if he had documentation supporting his claims. “I’m not a lawyer and didn’t realize they wanted legalese,” Brook says. He told them about the recordings and provided the paper research he had compiled. Brook remembers one of the committee members shrugging at the other, and minutes later announcing they’d be leaving early for lunch.

When contacted by The Local about Brook’s claims, Bailão’s office referred to the 228-page issue-by-issue response submitted by her legal team at the hearing in July 2011. The document asserts that the issues raised by Brook were “incoherent and based purely on [his] unqualified speculation and conjecture.” In regards to Brook’s allegations about the Co-op cab donations, the document states Bailão had “no knowledge of this assertion” and that Brook failed to identify which part of the Act was contravened “and how such a contravention would be attributable to [Bailão]”

An audit wasn’t ordered after the committee’s deliberation.

“If you don’t know the numbers for the rules being broken, it gives them an out—a way to ignore you,” Brook says.

Chaleff says the grounds for an audit should technically be a low standard, comparing the process to asking a judge for a search warrant. “The judge just needs to be convinced that there’s probable cause to believe a crime may have been committed,” he says. “In this case, you don’t need to prove somebody actually contravened the act… applications are so many rungs lower than that.” Yet, Chaleff attributes a lot of his success with previous applications to having lawyers in his orbit who provided expertise pro-bono. “I could file some of these on my own, but I don’t know how many would be successful.”

Retired teacher and activist David DePoe was able to secure legal support when he filed audits in 2011 against Rob Ford and Giorgio Mammoliti, but not an outcome he deemed appropriate. Like Chaleff, he witnessed no action taken against Ford. For Mammoliti, the audit found he overspent his $27,464 limit by more than 40 percent. Four years after the election, Mammoliti pleaded guilty to four charges under the Municipal Elections Act and agreed to pay a penalty of $17,500. “The audit confirmed what I found, but they just gave him a little slap on the wrist,” DePoe says. “Somebody like me has to spend hours and days…you need a lot of support, for the regular everyday citizen to do something like this.”

“The penalty applied was insufficient for that level of corruption.”

We imagine elections as being like soccer games–refereed contests, with everyone playing by the same rules. In reality, they’re soccer games in which the referee doesn’t enforce the rules until years after the game is over, and only if a fan asks for an audit of a particular slide tackle.

Nine years after digging into Rob Ford, Chaleff has only seen one compliance audit that resulted in a removal from office, and it wasn’t even really his doing. After the 2018 election cycle, Chaleff wasn’t planning on filing any applications. Each one required around 50 hours of work for the submission alone, less if you got a lawyer involved pro bono, but still too much to take on with a one-year-old son and a full-time job. But when he received a call from political journalist Dave Nickle, asking if he’d looked into Ward 22 Councillor Jim Karygiannis’ expenses, Chaleff’s curiosity got the better of him. Upon a closer look, it seemed Karygiannis’ violations didn’t reside in grey areas. Rather, he was flagrantly contravening the rules. Chaleff submitted an application detailing how Karygiannis spent over double his authorized limit, including $81,000 paid in “transition honoraria” and more than $27,000 spent on a “fundraising event” that raised $0, two months after election day. (Karygiannis did not respond to request for comment).

While an audit was ordered in June 2019, Karygiannis was removed from office on November 6, after he filed an additional financial statement that showed he overspent on expressions of appreciation, triggering an automatic “forfeiture of office.” Essentially, it was a fluke—the actual compliance audit report didn’t come back until December 2021 and legal proceedings have yet to take place. “He got himself removed from office way faster than I could have ever done it through the compliance audit system,” Chaleff says.

For him, an ideal accountability system is a proactive one, with strong incentives for candidates to follow the rules in a timely manner. Chaleff envisions a centralized body set up to review the financial returns of municipal candidates, perhaps with a qualifier on what constitutes a review. “We shouldn’t have people who are under a cloud of questioning about whether they were democratically elected, continue to serve on our councils,” he says. “It feeds public cynicism about representatives and undermines confidence in our local governments.”

As it exists in Ontario, Chaleff says, the system enables candidates who are caught cheating “to drag their feet and make sure it takes as long as possible to get a resolution rather than to deal with things quickly.”

That was the case during a recent compliance audit of 2018 mayoral candidate Faith Goldy’s finances. The audit took almost three years, auditor William Molson wrote in his report, primarily because of “the Candidate’s lack of cooperation.”

In Karygiannis’ situation, the former councillor appealed the committee’s decision to order an audit on his expenses, not yielding until the Supreme Court of Canada rejected his attempt in September of 2020. While the committee finally considered the audit report in December 2021 and decided legal proceedings should be commenced against Karygiannis, they have yet to be carried out. The Municipal Election Act’s limitation period dictates that he can’t be prosecuted after November 15 of this year.

On the administrative side, compliance audit processes just aren’t on the front burner for municipalities, says Zack Taylor, the political science professor at Western University. “The clerk, who has the statutory responsibility of administering the Municipal Elections Act in Ontario, has a lot of other jobs to do,” he says. “Elections are this super important but super annoying thing that comes along every four years while they’re trying to do the rest of their job.”

“Clerks have told me that they don’t want to be the Auditor General. They don’t feel they have the powers or information to proactively monitor candidate spending during election campaigns.”

Municipal election rules are formulated by the provincial government and what applies to Toronto applies to all 444 municipalities in Ontario. Enacting a more proactive approach in Toronto would mean bringing one to small municipalities, places with just two or three employees that don’t have the money or resources.

“I don’t think the system makes any sense,” says Jack Siegel, an election lawyer who’s been involved in over 20 compliance audits, with experience defending candidates, pursuing compliance audits on behalf of citizens, and even advising auditors. “It makes no sense to me to have legal obligations, the possibility of charges being laid, and nobody with the public duty to enforce that law.”

Siegel thinks the finance provisions of the act are so poorly written that they’re difficult for candidates to understand and comply with. “I’ve never ever seen a candidate’s financial statement that was 100 percent compliant with what’s in the legislation.” He feels there’s value in making the process more corrective than adversarial, like how it works on federal and provincial levels, where officials review every single financial return that comes in and provide candidates with opportunities to make corrections. Siegel isn’t looking to thrust more responsibility onto Ontario’s municipalities—he believes Elections Ontario should and could expand the scope of what they do.

“They have the expertise. They’d need to adopt a new law which would then take a few months to implement.” Siegel says. “It’s not all that difficult, but I don’t think there’s any will to change it—and this applies to every party that’s run the Ontario government in the last 25 years.”

“We need to reframe our understanding of what municipal government is and what it means to seek public office there, and treat it with a lot more respect than we do now.”

In this political moment, not only is there a lack of appetite for large-scale change, but the current system seems to be on a downward spiral. In October 2021, a recommendation was approved by city council to no longer require candidates participating in the contribution rebate program to submit copies of their expense invoices to the City Clerk for public access. While candidates still have to file general financial statements, specific documentation like receipts and bank statements will only need to be retained privately until the next council takes office, in case an auditor requires them.

Chaleff says the removal of this requirement might make it so future compliance audits in Toronto don’t even get that far. “The invoices are the cornerstone of the compliance audit work I’ve done,” he says.

“Without those materials, none of the compliance audits that I’ve been involved in could have even gotten started. You’ve got to have reasonable grounds to ask for the audit.”

Despite the steps backward, Chaleff continues to try and help others understand how to use the tools available within the system. On a Thursday in June, he logged into a Zoom workshop hosted by political non-profit Progress Toronto, prepared to train the next generation of municipal watchdogs from his basement.

“Thank you to everybody for offering their time to learn about this,” he said. “It’s pretty nerdy stuff.”

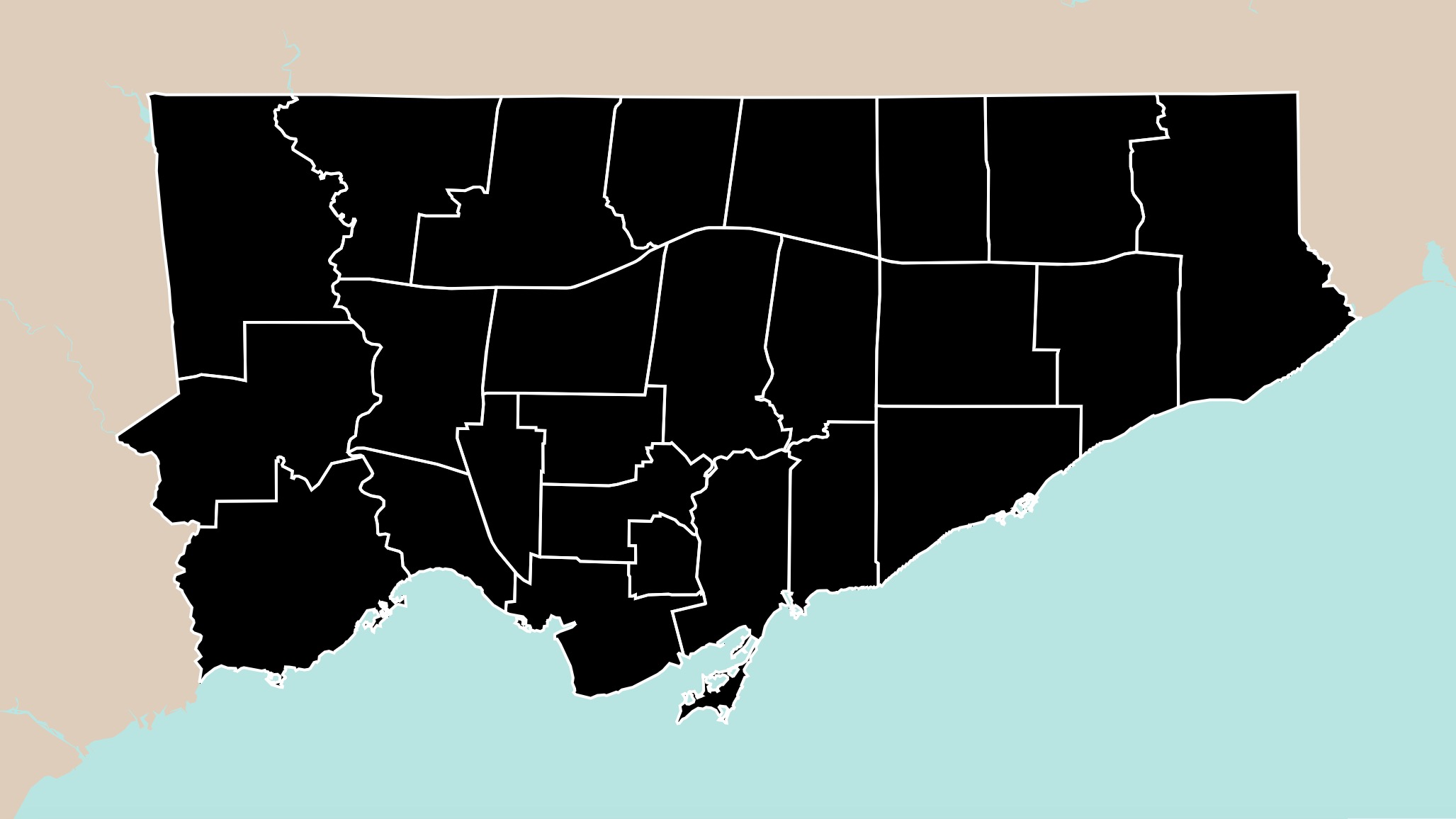

The 26 people with their cameras off—hailing from Scarborough, Willowdale, North York, Danforth, and beyond—listened as Chaleff explained how to spot cheating in an election, methods of gathering evidence, and the process for seeking accountability. Navigating to the city’s dated Toronto Meeting Management Information System, he gave attendees a screen-shared demo on how to search for candidates’ campaign finances.

Chaleff will probably take a look through the financial statements of this election cycle next March, even though he doesn’t really want to. He’s not sure if many others will. Ideally, he doesn’t want this to be a top-of-mind issue for regular Torontonians—he’s rooting for a system where everybody gets the equal scrutiny they deserve.

“A massive majority of Ontarians live in cities that make million dollar decisions every single day,” Chaleff says, lamenting how the current electoral regime imagines municipalities as small-time backwaters. “We need to reframe our understanding of what municipal government is and what it means to seek public office there, and treat it with a lot more respect than we do now.”

But Chaleff still believes in the value of working within the restraints of an unfriendly system. “It’s not fair that it’s this way, but they’re counting on you not taking an interest.”

“Our democracy is worthwhile,” he says. “There’s value in standing up and doing something.”