Before this week, Amani Awad was ready and hoping to distribute the COVID-19 vaccine at her pharmacy in Rexdale—but she never even got the chance to register.

Awad says that she never received the email prompting pharmacy owners to register for a chance to distribute the vaccine. She doesn’t know why: she’s got the space, the staff, and the certification to participate in vaccine administration.

“A lot of people are looking for the vaccine, and I keep asking,” she says from her store, John Garland Pharmacy, which she’s owned and managed for 11 years.

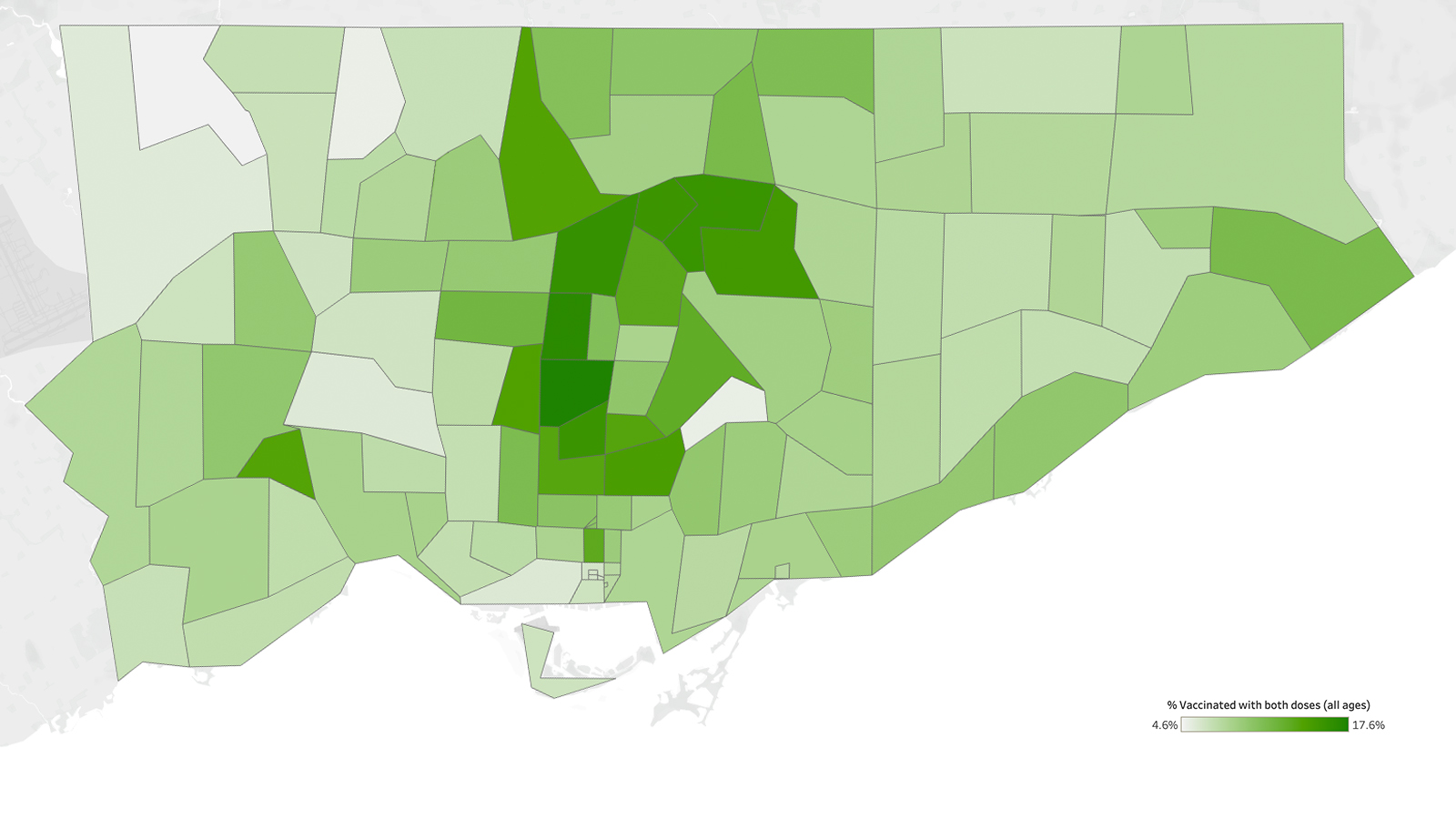

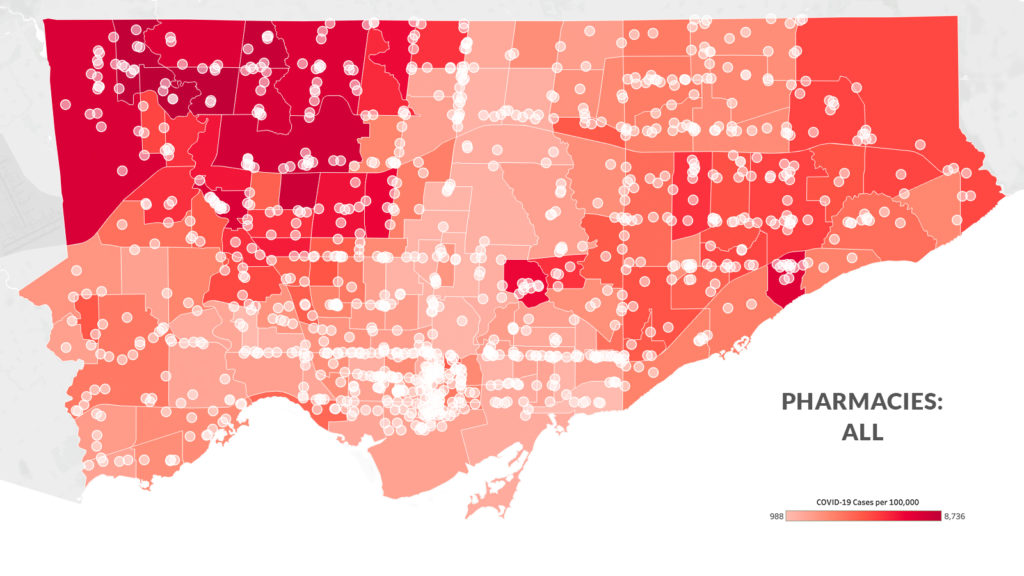

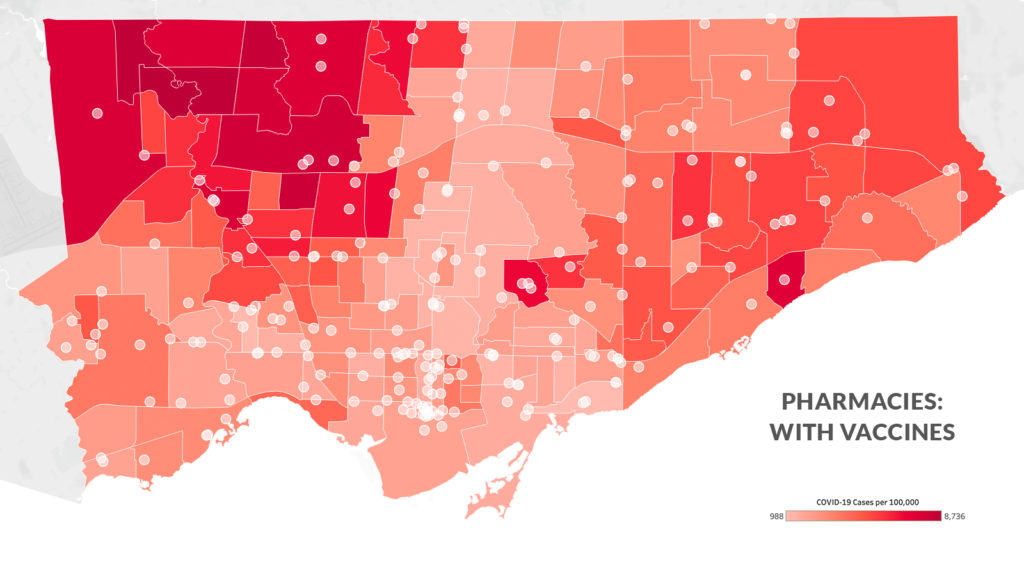

This past week, 224 pharmacies in Toronto began distributing the AstraZeneca vaccine to Torontonians over 60 years old, a pilot project running alongside the province’s mass vaccination program. But many of the selected pharmacies are clustered in the downtown core, with only a handful in the northwest of Toronto, where Awad’s pharmacy operates.

Many of her clients are older immigrants and refugees who are seeking out the vaccine, Awad says, but aren’t able to navigate the process of registering for it, given language barriers and lack of experience with the internet. Just earlier that day, she’d received a visit from several customers asking about vaccine registration. They told her how they tried calling participating pharmacies to register for the vaccine, but were told to register online. “They find it so difficult,” she says.

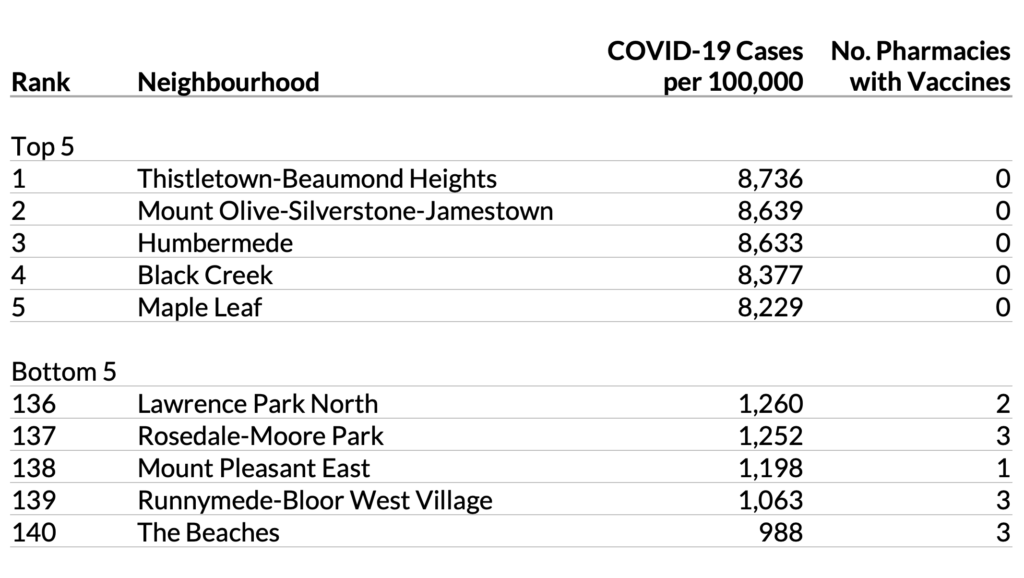

Even if Awad had been given the opportunity to distribute the vaccine at her pharmacy, she would’ve been the only one in the Mount Olive-Silverstone-Jamestown neighbourhood, a corner of Rexdale just south of Steeles that has the second-highest rate of COVID-19 infections in all of Toronto since the pandemic began.

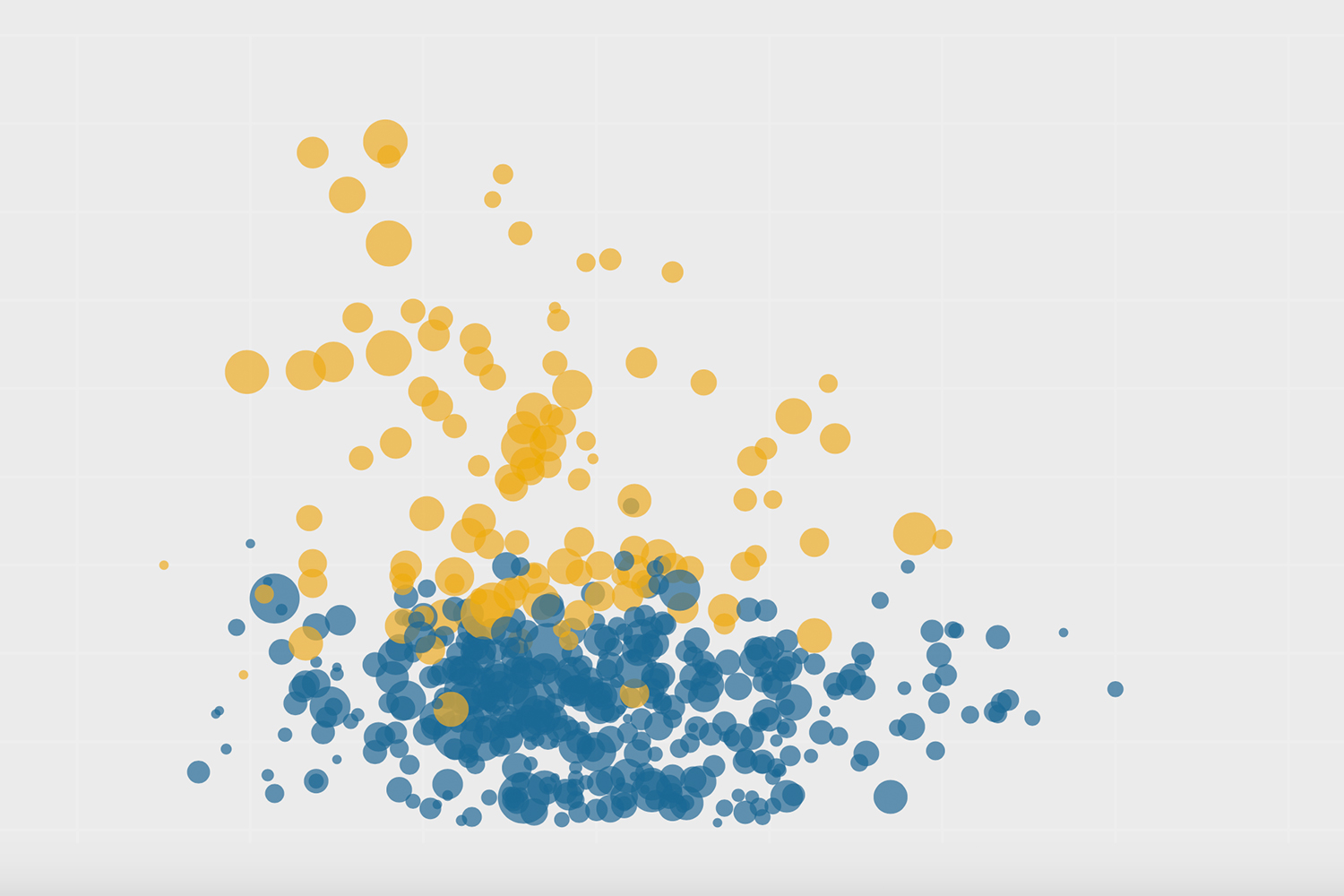

In fact, among the top five neighbourhoods for COVID-19 infections (all in Toronto’s northwest), none have a pharmacy offering the vaccine. In contrast, the five neighbourhoods with fewest infections have 12 pharmacies offering vaccinations.

Advocates have already spoken about how the vaccine rollout at Toronto pharmacies this week left thousands behind, prioritizing the city-centre over areas that are at far greater risk—and that house lower-income and racialized populations already worst-hit by the pandemic. With greater vaccine demand and significantly lower supply, residents of northwest Toronto will be forced to wait longer; some of the most vulnerable and underserved community members also don’t have access to a vehicle to make the trip to the nearest participating pharmacy five neighbourhoods over, let alone downtown.

This disparity isn’t because of a lack of pharmacies in the northwest. In the five neighbourhoods with the highest COVID-19 rates in Toronto, there are 25 pharmacies in total—they just haven’t been selected to distribute the vaccine. Instead, the disparity points to another dividing factor: the pharmacies distributing the vaccine are disproportionately corporate-owned, and most of the corporate pharmacies in the city are in its downtown core, an area overserved by a high concentration of pharmacies and comparatively low levels of health risk.

The Local’s analysis of the city’s pharmacies found that while those owned by large corporations—specifically Loblaw, Metro, Sobeys, McKesson (which runs Rexall), Wal-Mart or Costco—make up a little over a third of all pharmacies in Toronto, they comprise 72 percent of the pharmacies chosen to distribute the vaccine first.

The Toronto Star reported in early March that pharmacies administering the vaccine were set to be paid $13 per dose by the Ontario government, adding up to an estimated $2.1 million in the initial stages of the pilot program. This figure will likely grow as distribution expands, and appears to disproportionately reach corporate pharmacies already making significant profits over the course of the pandemic.

In areas like Rexdale, Black Creek, and Humber, small independent pharmacies are the backbone of the health care infrastructure. When wait times for family doctors are high, pharmacists can serve as interim medical support, see community members more regularly than doctors do, and be more accessible than the nearest clinic. Awad reports that when doctors declined to see patients in person during the pandemic, regular patients would turn to her with their questions.

It’s unclear why the provincial government chose to underutilize this crucial link in the health care infrastructure—did Awad’s pharmacy just happen to slip through the cracks? Did most independent pharmacies not fit the requirements for distribution?

Part of the problem is capacity. The Local spoke to pharmacists in northwest Toronto who reported that while they would’ve loved to administer COVID-19 vaccines, their independent stores were simply not capable of the work. “Because of our limited space, and the COVID restrictions of spacing, in terms of being two [metres] away, we can only have one person in the pharmacy at a time,” says Christina Habib, who has been running Community Choice Pharmacy in Black Creek for four years.

But Habib points out that space isn’t the only concern. “[Corporate pharmacies] can coordinate how they’re going to register online for the COVID vaccine, they come up with all of the resources needed, they have people that are working behind the scenes, while the people on the storefronts are just able to meet the needs of the pharmacy itself.”

Other pharmacists from the area confirmed their staffing and size meant they couldn’t distribute the vaccine. While there are some independent pharmacies approved to administer the vaccine, they make up just over a quarter of all the participating pharmacies, and a majority of them are downtown.

The question remains: why weren’t more of the northwest’s Shoppers Drug Mart, Rexall, and No Frills pharmacies approved for vaccine distribution? While these corporate pharmacies have comparatively fewer branches in the northwest, they do have a significant local presence. Yet, only a fraction of these branches carry the vaccine.

Loblaw, Rexall (owned by McKesson, which also owns Guardian/IDA pharmacies and The Medicine Shoppe), and the Ministry of Health did not respond to our request for comment.

If May knew where to access the vaccine—and how to get there—she says she’d be first in line for a dose.

May, who is using a pseudonym for privacy concerns regarding her living situation, is 79 and resides in Toronto Community Housing near Jane and Wilson. From her window, she can see a community centre; she doesn’t understand why the elderly residents of the building, including herself, can’t be vaccinated there.

“If [the vaccine] was offered in the community, I could walk to get it,” she says. But the closest vaccination centre is a 30-minute walk away, and May uses a walker. She doesn’t know anyone who could drive her, and at a time when taking public transit carries significant risks, there are few affordable options to get to a vaccine. But before travelling to receive the shot, she faces an even greater obstacle: she doesn’t own a computer, and can’t register online.

“[I feel] like I’m being left out, or seniors are being left out,” May says. “In Community Housing, nobody has even approached us on where we could even go and get the vaccine.”

While the city has been doing outreach in some social housing, they have yet to reach May—she’s unsure of when she’ll even be able to register.

Meanwhile, in the downtown core, one independent pharmacy owner distributing the vaccine tells us he’s already administered the vaccine to visitors from outside Toronto, including residents from as far as Niagara Falls.

For residents of the northwest, the inequity of the vaccine rollout is a continuation of the failures of the past year, and of an underserved, inadequate medical infrastructure.

“In a way, they’re invisible,” says Cheryl Prescod, Executive Director of the Black Creek Community Health Centre, which has been a hub of community outreach and medical services since long before the pandemic. “People in northwest Toronto, other areas that have been hard-hit, they’re the workers, they’re the folks who have been keeping us afloat. […] They deserve to be protected, and we owe it to them to make the vaccination process as easy as possible.”

“I think if we were to really put an equity lens into the decision making, [this] would have been avoided,” she continues. “More resources would have been put into some of those communities instead of the other way around—which is, again, robbing from where things are really bad, and really shoring up the resources in other places.”

To Prescod, an effective vaccine rollout would have had the same supports in place that an election does: paid time off to get vaccinated when eligible, easily accessible vaccination locations, and knocking on doors in low turnout communities to ensure participation. Her team has been doing that last step, but without adequate action from the province and the city, Prescod worries that we won’t be able to catch up with rising COVID variant numbers.

“This is a race to the finish,” she says. “If we don’t take care of one part of our city, will we even contain this?”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.