At 8:45 p.m. on a mid-May Sunday, up on the sprawling second floor of what used to be a Target, the team at Thorncliffe Park’s vaccination clinic delivered their 10,000th dose of the day. People rushed to a monitor that had been keeping tally since the clinic opened at 7:00 a.m.; as the number flipped over, a cheer went up.

Michael Garron Hospital nurse Phillip Anthony snapped a photo in the middle of the crowd. A co-chair of the Toronto Mobile Vaccine Strategy Table, he’d helped put the clinic together and agonized over maximizing its throughput, ensuring all the registration clerks and pharmacy staff and vaccinators moved in balletic coordination to average more than 650 doses an hour. The work paid off—but even before Thorncliffe notched its 10,000th immunization, Anthony’s mind drifted. “I was thinking, okay, where do we go from here?” he says. “What’s the strategy for the different areas we need to reach? What’s next?”

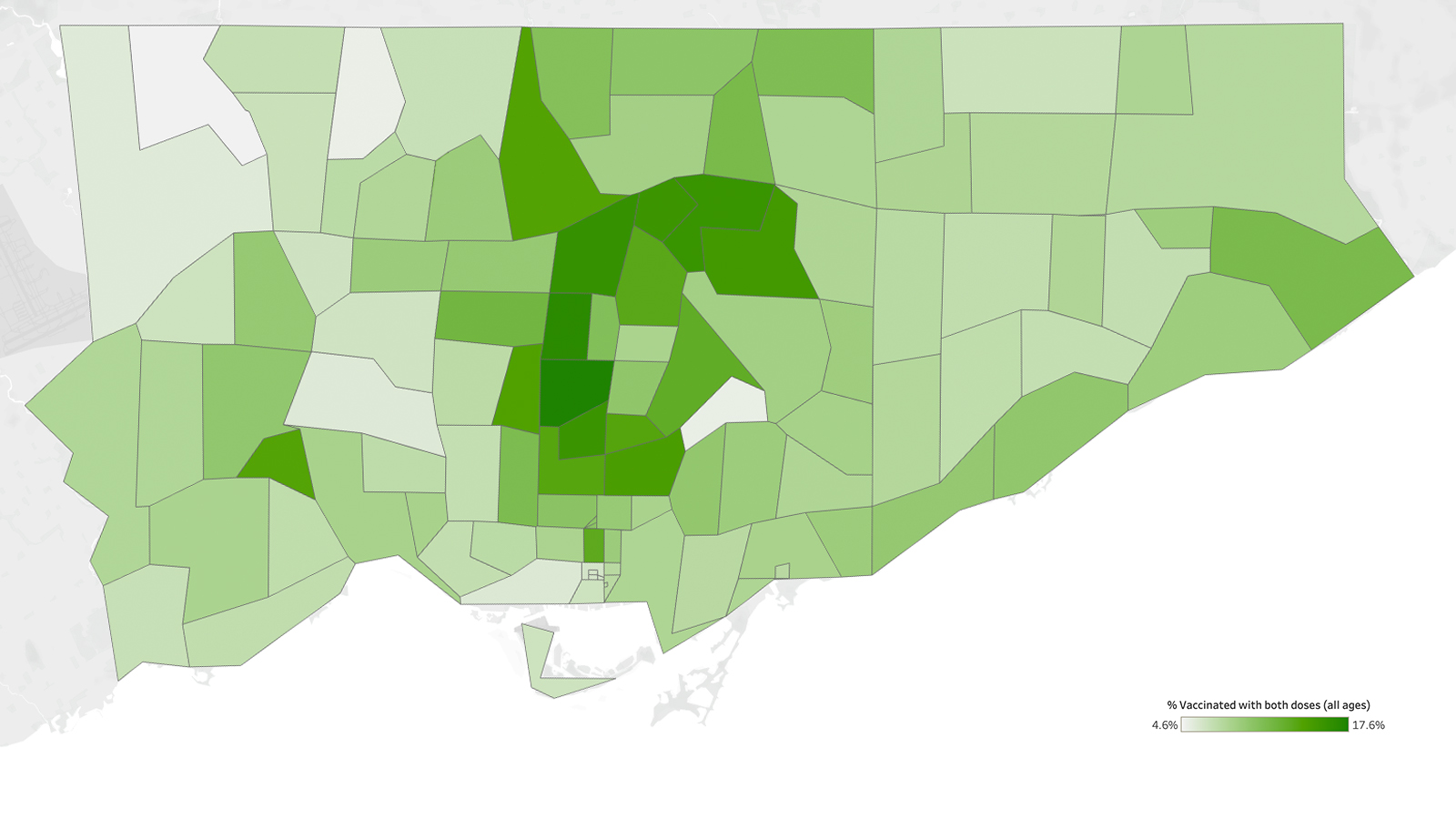

A little over two weeks later, on June 1, the city hit a milestone of its own: 70 percent of the adult population had received at least one dose of a COVID vaccine. It marked a 30 percent jump in vaccination in just a month. To date, 9 city-run mass immunization clinics, some 170 pharmacies, 30-odd hospital-run clinics, and hot-spot pop-ups across the city have together administered more than 2.5 million shots.

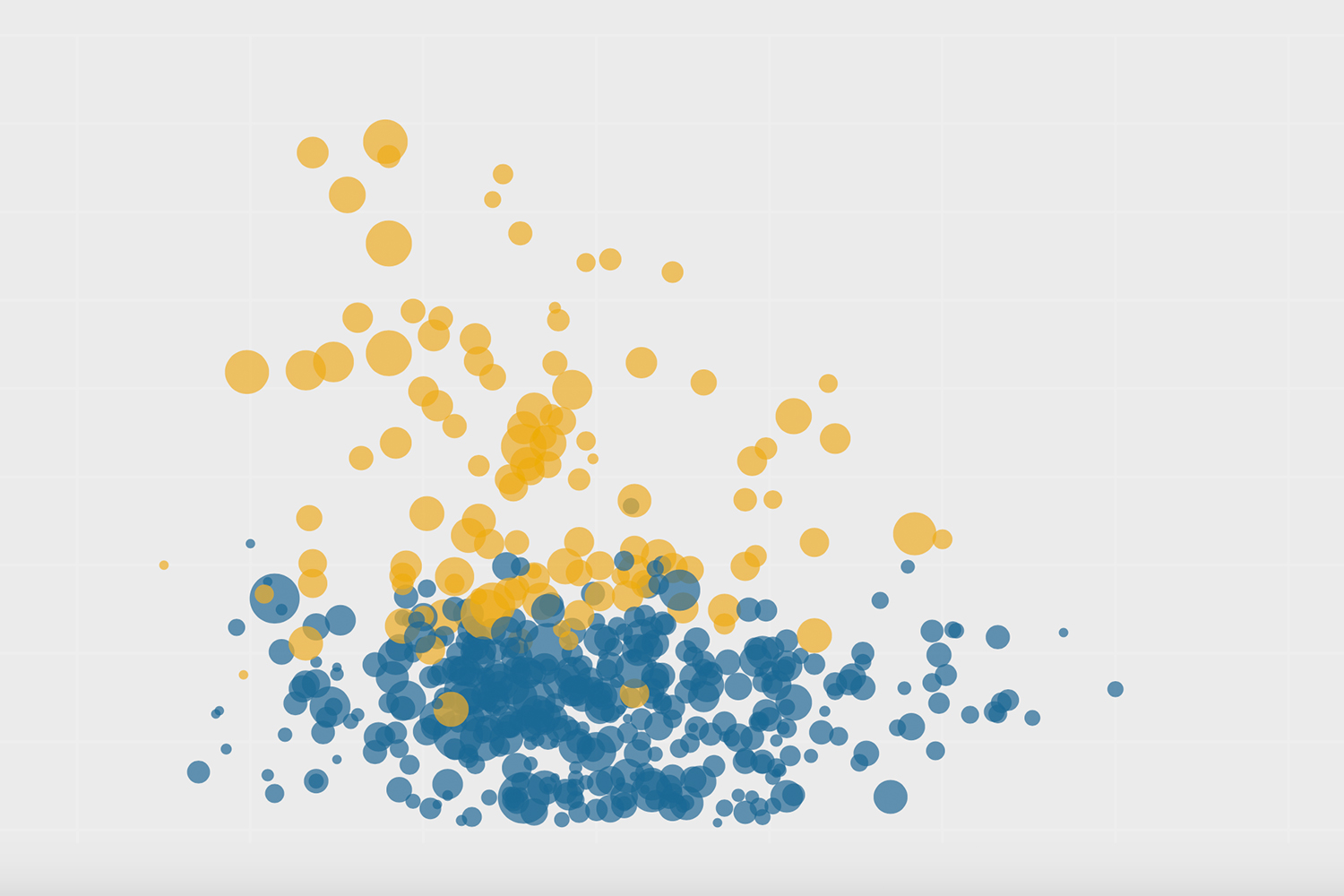

But these hugely impressive numbers conceal some more concerning ones. Roughly a quarter of Toronto residents aged 80 and older remain unvaccinated, a number that has barely budged since late March. Nearly a third of people between 30 and 54 years old—which is to say, the bulk of the workforce, and the group likeliest to be caring for young children or older parents or both—haven’t had their shots. No one’s quite sure how many people with disabilities still need to be vaccinated, because that data isn’t collected here, despite the fact that people with disabilities have made up 60 percent of all deaths involving COVID in the U.K.

“The mass vaccination clinics and high-volume pop-ups were the perfect strategy for siphoning off pent-up demand, and there was a lot of it,” says Sophia Ikura, executive director of the Health Commons Solutions Lab at Sinai Health. But it’s a strategy that has best served Torontonians with the time, resources, language, and mobility to chase the vaccines—to navigate a complex booking system and then drive to a distant clinic, or stand in the sun outside a pop-up they found out about from Facebook, or call every Rexall with a 905 area code until they land a booking.

To reach the rest—the homebound, the hesitant, the folks still contending with barriers to access—it’s going to take a slower, more deliberative, more distributed approach. Instead of asking people to fit their lives around vaccine appointments, we’ll need to bring vaccines straight to the people. That’s what Phillip Anthony found himself thinking that Sunday evening in Thorncliffe Park. “We understood mass immunization clinics for all adults were only going to last so long,” he says. “What’s next is moving to hyperlocal, low-volume clinics.” It’s time to go bespoke.

Because if we don’t, and if we can’t reach a good chunk of the final 25 percent, the consequences are considerable. Not just for the continuation of COVID—though you can’t shut down community spread unless the vast majority of a community is immunized, and the longer the virus spreads, the more opportunities it has to evolve into a variant that could breach even a vaccine’s protection. But the pandemic has, as we often hear, held a mirror to our society. “And based on our policies and where we put our resources, we’ve shown that there are groups of people we don’t really care about,” Ikura says. “There’s a reckoning we need to do here. Are we finally going put a stake through the idea that there are people we’re okay with leaving behind?”

“We understood mass immunization clinics for all adults were only going to last so long. What’s next is moving to hyperlocal, low-volume clinics.”

Since the chaotic first days of the vaccine rollout, which repeated the same familiar disparities across race, neighbourhood, and income that we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, health care workers and volunteers have made huge efforts to reach communities that face barriers to getting their shot. At Jane and Finch, for example, organizers are bringing vaccines to people’s literal doorstep. Black Creek Community Health Centre helped set up clinics in the San Romanoway buildings, where nurses went door to door, floor by floor, to administer doses. There was a two-day clinic in the rec centre of one of the apartment towers on Falstaff Avenue, a two-day clinic put on with the Vietnamese Association at St. Jane Frances Church, and several more since April.

At the drop-in pop-up clinic for Black, African, and Caribbean communities last month, a DJ spun reggae and soca music outside, while the freshly immunized left with beef patties and chicken soup. “Getting vaccinated to protect you against a disease is a moment to be proud—it’s something to celebrate,” says Akwatu Khenti, chair of the Black Scientists’ Task Force on Vaccine Equity.

It was a customized approach that worked for the community: Over two days, vaccinators at the Jamaican Canadian Association clinic administered more than 1,300 shots. But not all populations can be turned out the same way—raucous pop-ups with outdoor lines don’t serve older adults or people with disabilities nearly as well. “If I’m autistic, or have sensory issues, or get overwhelmed by loud music and crowds, those pop ups would just kill me,” says Yona Lunsky, director of the Azrieli Adult Neurodevelopmental Centre at CAMH.

Last month, she helped organize a clinic that supported people with developmental disabilities, where cozy beanbag chairs and TVs projecting underwater scenes kept the atmosphere calm, and where the entire vaccination process—from registration to getting the shot to waiting the mandatory 15 minutes—could happen at a single table. “Going from station to station is hard for people who physically can’t move as easily, and it’s also hard for people who have a difficult time with transitions,” Lunsky says.

“Accessibility is often thought of in terms of wheelchair accessibility, when really, there’s more breadth and depth to universal accessibility,” says Sara Rotenberg, a Rhodes Scholar focusing on disability inclusion policies. Different barriers exist for different individuals, but a number of low-lift, inexpensive actions can help everyone who wants a vaccine to get one. Rotenberg rattles off a few places to start: “Having multiple ways of booking, rapid lines, clear signage, accessible transport, easily identifiable staff to help with accessibility, and information about accessibility online. More specialized clinics and home-based vaccination will help ensure we reach everybody.”

That includes the roughly 3,000 homebound seniors in Toronto who still haven’t received their first dose, due to mobility issues, transportation barriers, or the inability to speak with a trusted source about their concerns around vaccination. And then there’s the subcategory of seniors who are so isolated that nobody—not a primary care physician, not Toronto Paramedic Services, not a building manager or community leader—knows about them.

“There are people we see all the time who have had no connection to the health care system or social-service footprint for decades,” says Sinai Health geriatrician Nathan Stall. “It’s almost like, if a tree falls in the forest and nobody hears, how do we know about it?” To locate these older adults, it’s essential to go door to door. Stall did exactly that in North York over the Victoria Day weekend, carrying vaccine in his cooler to capture anyone who might decide they wanted a dose. By the end of the weekend, 30 homebound seniors—and some of their unvaccinated caregivers—had shots in their arm.

“We’re at the point where we need to reach every single resident where they are, whether that’s in their home, in their place of worship, at their workplace, or online,” says Toronto board of health chair Joe Cressy. At the end of May, the City announced a VaxTO campaign, employing get-out-the-vote tactics like door-knocking and phone banking to get out the vax. The City called upwards of 650,000 people on a recent weekend and offered to patch them through directly to book an appointment; thousands took them up on it. Vaccine booking information is now available in 14 languages via text. And the City is providing community agencies and councillors with the infrastructure they’ve built for VaxTO, so local organizers could, for example, run a telephone town hall in Cantonese for seniors living in an Alexandra Park apartment complex.

Every one of these community-based interventions is critical for catching the populations skipped over—but we need to keep them up, redoubling efforts, circling back to rec centres and apartment hallways, and combining strategies to reach people who might otherwise be missed. “The other day, we did a small clinic in a community church that runs a food program,” says Cheryl Prescod, executive director of the Black Creek Community Health Centre. People didn’t come in for a vaccine, but once they realized one was available, several agreed to roll up a sleeve. “It’s these low-barrier, high-accessibility features that allow us to go deep into a community,” Prescod says. “So there’s not just breadth, but depth.”

And these interventions must remain properly resourced, especially as momentum in the city shifts to administering second shots. “Community partners have been relentless about knocking on doors and doing tiny vaccine clinics,” Ikura says. What they need in return is simple: access to the provincial COVax system to register people, a bit of IT help, and some pharmacy support for the vaccines. “But we’re hearing from our partners that they have to go begging for these things, because attention has moved to second doses,” Ikura says. “We need to be appropriately resourcing community partners to do the stuff they’re expert at.”

When we move fast on big goals like vaccination, there is a temptation to focus our ambitions on benchmarks like herd immunity…But if our vaccination rollout overachieves in certain areas and leaves chasms in others, the result remains a gap in protection overall.

Customizing strategies for better access is one way to catch Toronto’s unvaccinated population. Another is to package information that speaks to them directly. Some of that will necessarily be practical: People are more inclined to book a vaccine or drop into a clinic if they know that it will be staffed by workers who can answer medical questions in their own language, or that it will offer a variety of accessibility features, or that it won’t require people to produce a health card or photo ID, which can be a considerable barrier for migrant and undocumented workers.

But information also needs to be delivered in a manner that unravels hesitancy—and that is more art than science. Since February, the Black Scientists Taskforce on Vaccine Equity has held roughly one town hall a week, often stretching three hours long, to answer questions and lay out risks. “We haven’t been lecturing people, presenting ourselves as this indispensable source of evidence-based information,” Khenti says. “It’s also not our job to rebuild people’s confidence in pharmaceutical companies.” At these town halls, they don’t debate. They don’t escalate. They never dismiss someone’s concerns as ridiculous or far-fetched. “We give respect to questions and try to answer them in a way that builds trust.”

The importance of trusted sources is why he—and Stall, and Ikura, and Lunsky, and Cressy, and virtually everyone interviewed for this story—emphasizes the need to include primary care in the vaccination rollout, which the province has so far failed to do. Khenti estimates that at any given town hall he’s led, 10 to 15 percent of participants are stubbornly set against the vaccine. “I believe those people will only respond to their primary care physicians, because it’s a long-standing relationship and they have a position of respect,” he says. “When your physician says you need to stop drinking or you need to stop smoking—or you need to get the vaccine—people take it more seriously.”

In their absence, community ambassadors have been doing heroic work reaching and persuading populations so far missed by the rollout, especially when it comes to those on the vaccine fence. Recruited by community agencies and grassroots groups, and funded by a $5.5 million outreach grant awarded by the City in mid-April, these ambassadors are “our eyes and ears on the ground,” says Aina-Nia Grant, who runs Toronto’s community vaccination mobilization and engagement program. They set up tables in apartment lobbies, drop off flyers, knock on doors, speak to neighbours in grocery stores and bus stops, all to devise vaccination strategies that are hyper-attuned to the community and that get people to roll up their sleeves.

“Civil servants can go out and talk about the greatness of the vaccine forever, but that’s not what changes people’s minds,” Grant says. “They need to hear it from trusted community residents who can reach and support those who need to be vaccinated.” Some 280 community ambassadors were recruited with the initial grant, but they’re spread thin, Ikura says, and could use reinforcement across the city. And that will require more funding. “We can’t ask people to do this as volunteers,” Grant says. “People’s lived experiences and community trust are expertise, and you have to pay them for it, just as you’d pay them for their master’s degrees.”

Complementing that expertise with social and demographic data would help communities identify gaps in vaccine coverage and then refine strategies to fill those gaps—but there’s been no mandate from Ontario to collect information about race, ethnicity, language, or income, and no scripts or direction about how to go about doing it. These are sensitive issues, especially for populations with a long history of surveillance and systemic discrimination in the health care system; it’s essential for people to understand that nothing about the vaccine is contingent on their answers.

But this is tricky, delicate work, and without a provincial mandate, it’s left to the clinics themselves to decide whether to collect the data and how. Some, like Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre and Black Creek Community Health Centre, have been asking questions in registration lines or waiting areas, where the response rate has been upwards of 90 percent. But they’re the exception: Ikura estimates that, right now, fewer than 1 percent of the vaccinated population have been asked about race, ethnicity, or income. “And we know what happens if we don’t collect the data,” Prescod says. “The communities that have been left behind historically will continue to be left behind.”

When we move fast on big goals like vaccination, there is a temptation to focus our ambitions on benchmarks like herd immunity: As long as the city can get to 80 or 85 percent uptake, we reason, we’ll be in good shape. But if our vaccination rollout overachieves in certain areas and leaves chasms in others, the result remains a gap in protection overall. As Toronto accelerates towards its second-dose summer, we can’t lose sight of the people who’ve yet to receive their first shot. “We know we’re not safe until everyone is safe,” Prescod says. “We have to take care of us all.”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.