As 39-year-old Gavin Cole waited patiently outside the Jamaican Canadian Association building in North York in the early hours of Saturday morning, he was just glad the day had finally come.

Arriving shortly after 6:00 a.m., he was first in line for a weekend-long pop-up vaccine clinic geared toward Toronto’s Black community. Cole was one of many who had tried unsuccessfully for weeks to book a vaccine through the province’s online booking system.

“Honestly, I feel so relieved,” he said. “I’ve always been a proponent of health and trying to protect myself and loved ones…And I’m happy that so many people are here in line.”

The pop-up clinic is part of the Black Health Vaccine Initiative, a collaboration between the Black Physicians Association of Ontario (BPAO) and a number of local organizations servicing the GTA’s Black community. The events are open to all members of the Black, African, and Caribbean communities who are 18 and above, regardless of postal code.

Clinic doors wouldn’t open until 10:00 a.m., but by just after 7:00 the line was already wrapping itself around the building. The BPAO has been running pop-ups like this for weeks across the city to help combat low rates of vaccination in a community that has already been hit hard by COVID.

“I realized that we really needed to be involved and try to improve rates of vaccination for the Black community,” said Dr. David Esho, physician lead for the Black Health Vaccine Initiative and a member of the BPAO. “We think our strength is partnering with agencies that have a long history of working in the Black community, and then we can provide support through education, advocacy, and potentially vaccination as well.”

Black Canadians have been disproportionately affected by COVID—particularly in Toronto, the city with the country’s largest Black population. February data from the city of Toronto found that we make up 9 percent of the city’s population but represent 13 percent of hospitalizations due to COVID (comparatively, white people make up 48 percent of the city and accounted for only 23 percent of hospitalizations).

The reasons for this disparity have been well-documented. For one thing, Black people in the city are usually overrepresented in precarious essential work. Almost one-third of employed Black women (31.7 percent) worked in health care and social assistance in January 2021, compared to just 22.9 percent of white women. We’re also more likely to reside in multi-generational households and in denser, lower income neighborhoods where the disease has spready more readily. These factors have made Black Torontonians far more susceptible to the spread of the virus than our white counterparts.

On top of this, vaccine rollout in the province has been a huge mess, a trend that has impacted the Black community in its own unique way. In a stunning April incident, for example, Black and other racialized communities were discovered to have been removed from the eligibility list for the province’s Phase 2 vaccine rollout.

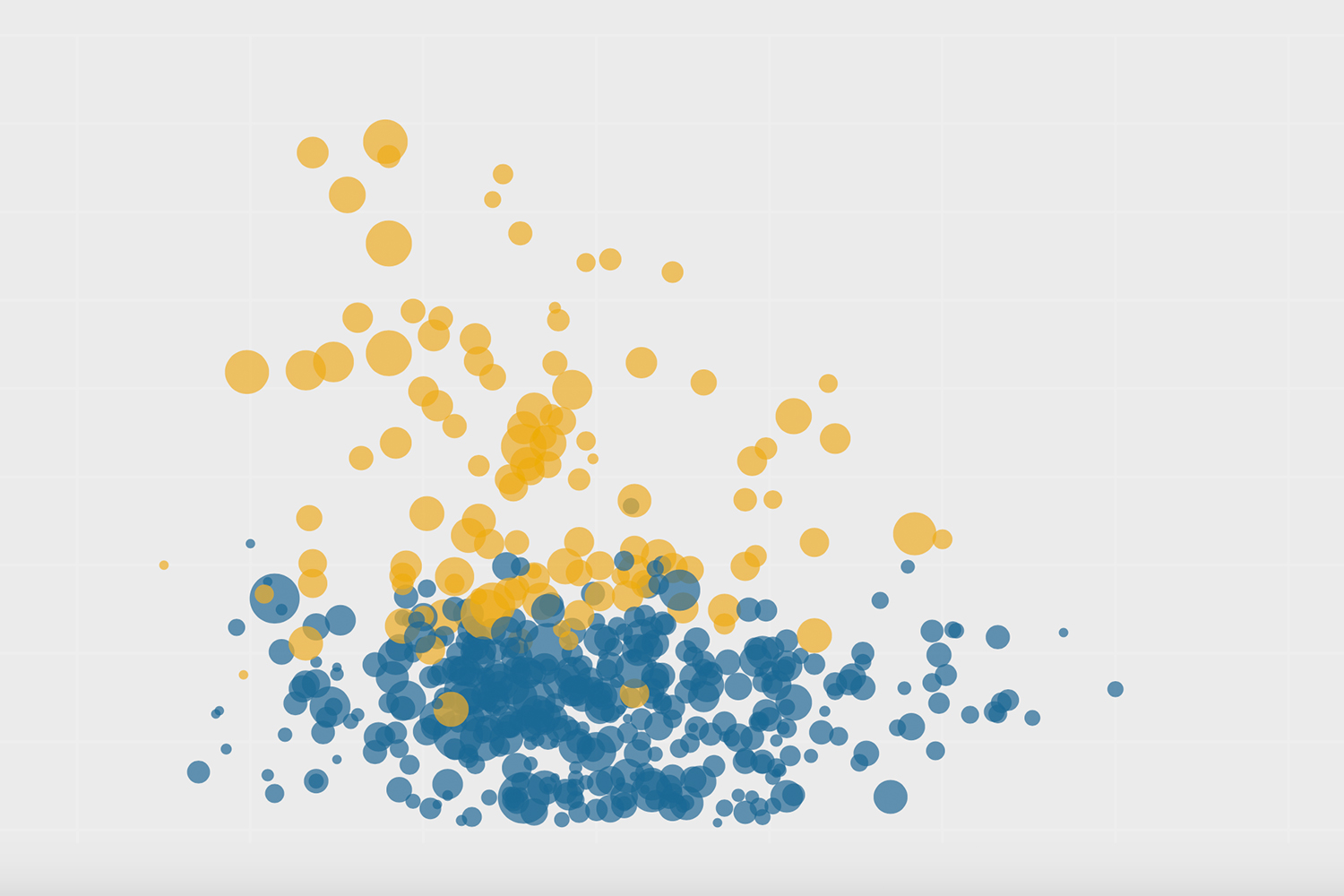

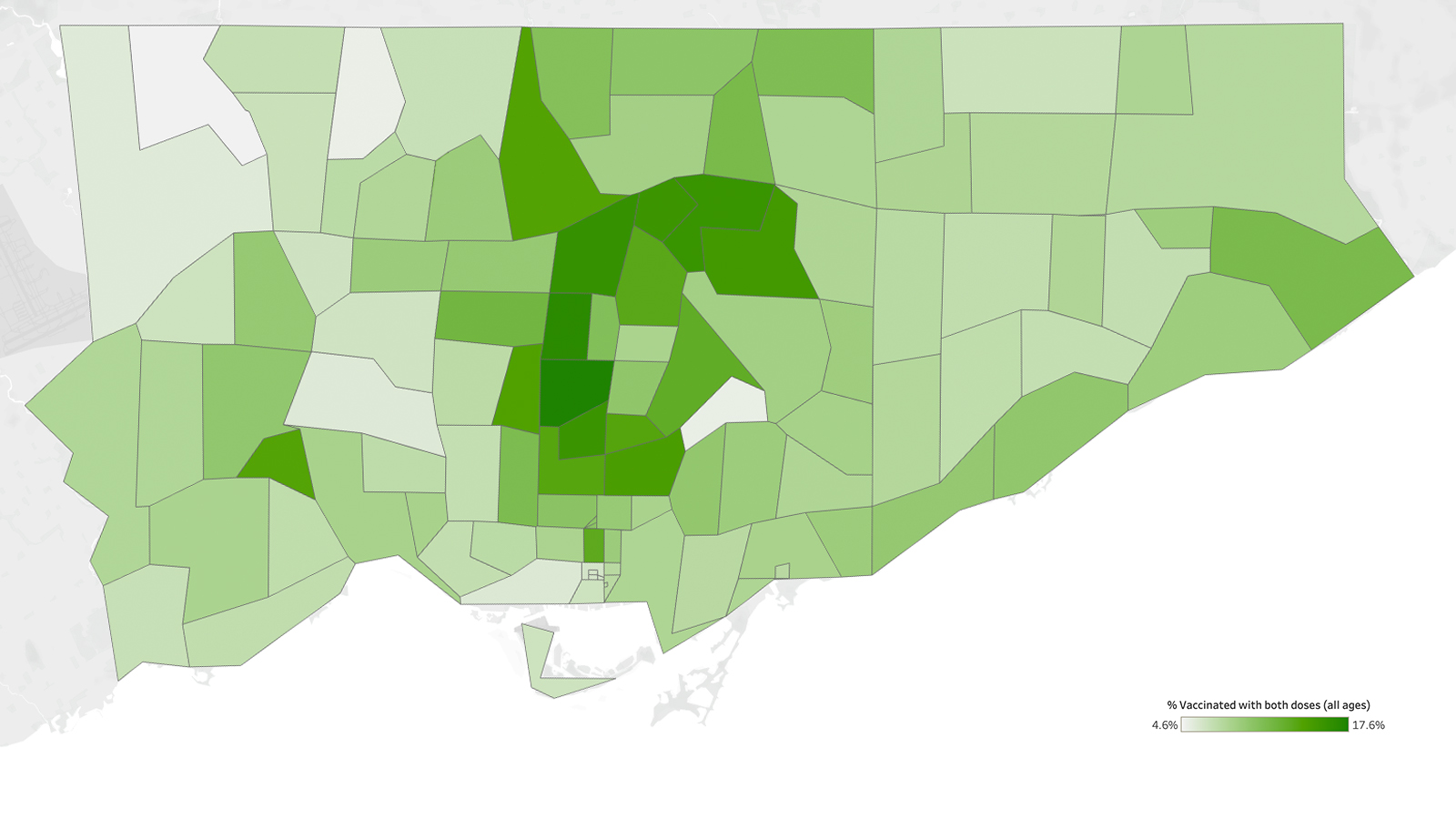

“If we look at the hot-spot postal codes, the ones that have a large population of the Black community are still disproportionately seeing lower rates of vaccination, and we’ve been slower to get to those communities as well,” said Esho.

Early vaccination numbers showed that the neighbourhoods hardest hit by COVID had a disproportionately low number of pharmacies offering the vaccine. In fact, analysis by The Local in April found that there was not a single pharmacy offering the vaccine in the five neighbourhoods with the highest COVID infection rates in the city. In Black Creek, for example, where 29 percent of the population is Black, there were a number of community pharmacies, but none carried the vaccine.

“I think another issue may be the hours that we often run for vaccination clinics,” Esho said. “[They] may not be the times when people who have less flexibility in terms of working from home, can come into a mass vaccination centre to be vaccinated.”

Even the process of trying to book a vaccine appointment through the province’s online system presents barriers for many seniors and others in the Black community with limited online access, and little time to navigate a labyrinthian phone booking system.

“A number of seniors had access issues, they weren’t able to get an appointment,” said Adaoma Patterson, president of the Jamaican Canadian Association (JCA), which hosted the event this weekend. “They’re not online, and then the wait on the phone is really lengthy.”

Residency status can also create questions in terms of access to the vaccine. As of 2016, there were about 44,285 Black immigrants in Ontario who were non-permanent residents, such as migrant workers.

“One of the other populations that the JCA in particular has been concerned about are the migrant workers and farm workers, because many of them are now here for the season,” said Patterson. “They don’t have access to information, and Wi-Fi is often a problem in the farms because they’re out in the country and in the rural areas.”

But aside from sheer access, many in Toronto’s Black community simply do not feel safe receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. 2020 data from the city of Toronto found that the highest rates of vaccine hesitancy in the city were among Black people of African and Caribbean descent (about 30 percent); and there are reasons for this wariness.

Black people have a historically fraught relationship with medical institutions, including a long and disturbing history of being forcefully (or sometimes unwittingly) used as guinea pigs in an array of medical experiments. Add to this, the day-to-day racism that Black people experience themselves in health care settings. A 2021 study on anti-Black racism in the Canadian medical system outlined the pervasiveness of this problem in our health care structures, and called for tangible solutions.

“There is a lot of distrust in our communities of the healthcare system for obvious reasons like historic inequalities and even personal experiences that patients have had in the system to this day,” said Esho.

There are also a number of fairly basic questions that people in the Black community want answered—by a trusted source—before they take the vaccine. Dr. Akwatu Khenti, chair of the Black Scientists Taskforce on Vaccine Equity, told me that residents were asking about everything from what specific vaccine was being administered, to whether or not clinical trials had included Black people and if the vaccine would be safe for people of African descent.

“We’re addressing vaccine hesitancy because even though people are here [at the pop up], when you walk the line and talk to people, you find that for some, it’s still a question in their mind,” he said.

Floydeen Charles-Fridal, executive director of the Caribbean African Canadian Social Services, says her agency has been fielding similar questions from residents in the community. “You hear from our seniors that they just don’t have enough information, and when they get the information, it allows them to make a more informed decision,” she said.

This lack of information is something Patterson and the JCA have been trying to combat by hosting culturally sensitive information sessions, seminars and town halls. “We held a town hall for seniors who had questions and just wanted to speak to experts that looked like them, [who could] take the time to explain exactly what vaccines are, and just answer questions that they had,” she said.

The outsized impact of COVID-19, married with lower rates of vaccination in the Black community, mean that it has been much more difficult to manage the spread of the disease within a population that is already marginalized. And for the organizers of the vaccine clinics, their approach is a perfect match for these unique challenges.

Saturday’s event was an amalgamation of information session and vaccination clinic, and by the end of the weekend, the group had administered 2,231 doses. That number will only continue to grow, hopes Esho. While planning for more pop-up clinics, the BPAO is continuing to run a standing vaccination clinic in partnership with Taibu Community Health Centre in Scarborough and other community allies. BPAO physicians have successfully vaccinated about 250 people per day at that location, coming up to a total of about 2,350 vaccinations before last weekend’s event at the JCA.

The BPAO is still holding vaccine clinics in partnership with local organizations that serve the Black community, and groups like the JCA and CAFCAN are continuing to facilitate information sessions and find ways to reach members of their community who may not have access.

“When people see themselves in the experts that they’re talking to and that they’re receiving service and care from—and that we’re doing it in a loving and culturally appropriate way—you see the response is so much different,” said Patterson.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.