Looking back, Radhika Gandhi’s fight for Peel Region started the day her father caught COVID.

The 23-year-old is the daughter of essential workers who have lived in Brampton for over two decades. Her father, Kanaiya, was a worker and shop steward in a Woodbridge factory, which experienced an outbreak near Christmas last year. The earliest testing appointment Gandhi could book for him was four days later, on December 29.

On January 3, he was admitted to Brampton Civic Hospital, ten minutes away from their home, where he tested positive after a rapid test. Results for the test his family had booked wouldn’t arrive until a week later.

By then, he was being transferred to the Southlake Regional Health Centre in Newmarket, an hour drive away from their home. Doctors told Gandhi that her dad was stable in the ICU and they needed to free beds. She didn’t have a say in the decision, and no family member was allowed to travel with him. When he got there, his new medical team called Gandhi to ask what his previous team had told her about his medical status.

In the weeks that followed, Gandhi received just two more phone calls about her dad. One to tell her he was worsening, another to tell her he wouldn’t last 24 hours. A family friend drove Gandhi, her mom and her sister to Newmarket, a five-hour round-trip. The hospital would only allow one person to see him through a window in the door to his room.

Kanaiya Gandhi—a man who worked 40 to 60 hour weeks and then spent the rest of his day with his two daughters, at his local temple, or shopping at the mall—died on February 4, 2021, at the age of 58.

Today, Gandhi says she experienced all of Peel’s inequities in a matter of days: there was no effective paid sick day program, no rapid testing, and Brampton’s only hospital was too stretched to help him. And after news of her father’s death made headlines, people sent her negative comments blaming her father for putting himself and his family at risk.

After all this, it was the community that checked in on her family, fought for protections, and came together to ensure that what happened to her father didn’t happen to anyone else. So the 23-year-old decided to call her MPP and start advocating for her community, believing her dad would’ve done the same.

“I’ve spent most of my life on the sidelines and dismissed a lot of bad stuff that’s said about Brampton,” Gandhi said. “This pandemic changed a lot. It showed me that although we lived a pretty good life, being a family of essential workers, being people of colour, and living in Peel, we faced a lot more barriers and systemic racism than people from another region would have faced.”

Gandhi is not alone in feeling the urgency to fight for Peel Region. A groundswell of rage and frustration across Mississauga and Brampton has turned into constructive advocacy in the months since her dad passed.

Since the first day of the pandemic, the Peel community has been in the line of danger due to a chronic lack of health care resources, a rich diversity of racialized, multilingual communities, and an immense essential workforce. Peel’s cries for help, however, weren’t heard by elected officials. Instead, most of the assistance Peel needed came from a network of hundreds of volunteers who have spent every free moment fighting and advocating and caring for their neighbours.

Over the past year, Peel’s cultural and social agencies have completely revamped themselves to become de facto health care support systems. Places of worship have become food banks, social assistance providers, and mental health supports rolled into one. Young professionals have given up their nights and weekends to book vaccine appointments for workers and seniors; many have even set up the pop-up clinics with their own hands.

“I kept waiting for the government to do something. I kept giving them chance after chance to figure it out,” said Romana Siddiqui, a Mississauga mom and Ontario Parent Action network member. “But in April, everything just came to head. We realized that Peel was expendable, and no one was coming to rescue our community. We had to save ourselves.”

On April 25, Siddiqui along with two Peel teachers and a community organizer decided to host a spontaneous emergency Zoom meeting to figure out what to do. They reached out to union representatives, local doctors and nurses, teachers, labour organizers, anyone in Peel who was in a position to help.

This group of people, including Romana and Gandhi, many of whom met for the very first time, expressed their rage and anxiety and then came up with four demands: paid sick leave, vaccinations, protections for workers, and equitable health care.

They called their advocacy movement “Save Peel.”

“It shouldn’t have had to take volunteers and people who are unpaid to do some of the core work that should have been done here,” said Dr. Naheed Dosani, medical director of Peel’s isolation housing system, which was set up in partnership with dozens of Peel community organizations. “Peel survived the pandemic because help came from the blood, sweat and tears of their own community.”

“Every problem here is basically an issue of systemic racism. So, we responded the only way we know how to: we helped each other.”

Navi Aujla has been fighting for Brampton for her whole (29-year-old) life alongside her father Nahar.

Long before COVID started, the father-daughter team was putting on plays, organizing protests, and meeting with elected officials to demand more: more health care resources, more workplace protections, more job opportunities. The Aujlas watched as governments made promises to the community and then later retracted them. Brampton, one of the largest cities in Ontario, was promised its first university, the funding for which was revoked before the pandemic began. A hospital has been promised for decades, but the plans have shrunk to a new hospital wing.

As devastating as the pandemic has been in the region, for the Aujlas, none of it was unexpected.

“We’re just fed up at this point,” said Navi, who is currently working with Punjabi Community Health Services. “It’s been known for a very long time that our community is not getting what it needs and that we are being treated very unfairly. The laws do not protect us. The systems do not protect us. The government does not protect us.”

Last week, Nahar, a member of the Workers Action Centre, received a call from a Brampton warehouse worker who had tested positive. His company, which had been hiring temporary workers throughout the pandemic, gave him the required 14-day isolation period off work. When the worker went back to his job, the company said they didn’t need him anymore and let him go.

The Aujlas, who are also helping the Save Peel movement, have heard too many stories like this. Their first response is to listen and sympathize, make it known that this worker is not alone. They try to connect workers to various agencies for financial, health, and social support. Then they try to figure out how, or even if, they can fight the termination. Sometimes they win; sometimes they don’t. Either way, they are on the local community radio shows or online every day to try to raise awareness and demand change.

“This has been happening for decades,” Nahar said. “The government just doesn’t pay us its fair share of attention or resources. There’s a lack of will to do anything for Peel.”

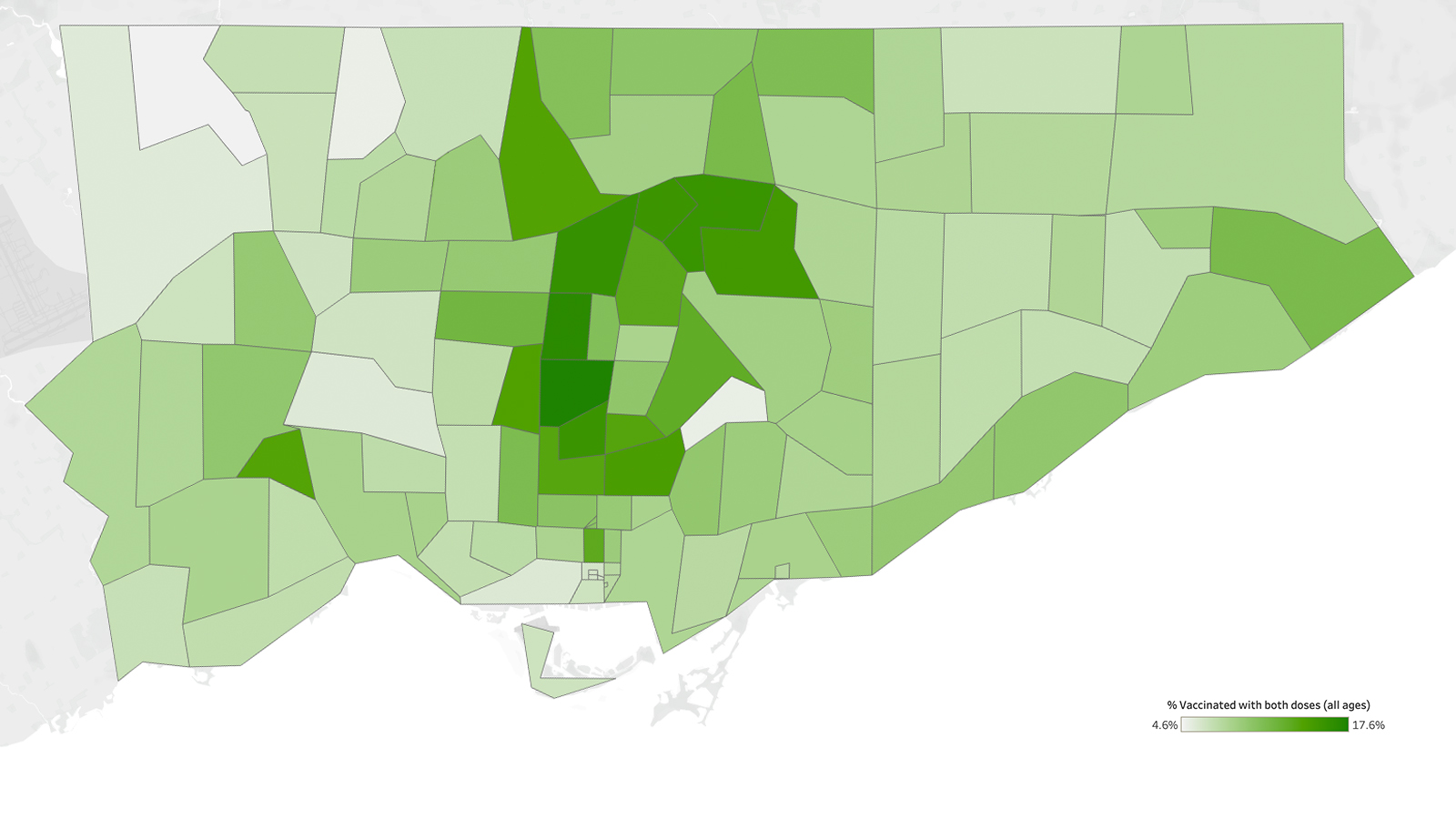

This was extremely evident throughout the pandemic, Navi said. Every member of the Peel community can recall every instance the government blamed them or treated them unfairly. On numerous occasions, Ontario Premier Doug Ford has pointed the finger at Brampton for high COVID cases and called it “broken.” Everyone in Peel will remind you that during Diwali and Eid the government forbade social gatherings, but decided to instate stay-at-home orders only the day after Christmas and the week after Easter. Meanwhile, essential workplaces—the many manufacturing and logistics companies located in Peel Region where COVID spread rapidly—were left open without any additional protection or oversight.

“Every problem here is basically an issue of systemic racism,” Navi said. “So, we responded the only way we know how to: we helped each other.”

For so many people in Peel, that help meant foregoing sleep, sharing their contact information widely, and answering every unknown number that called them at any time of the day or night. Private Facebook groups were set up asking communities to share the information of anyone who needed any kind of assistance during the lockdown. WhatsApp group chats became the first stop for COVID information.

Peel has never had a cross-agency collaborative system to help people who fall through the gaps of its health care or support system, so all these efforts were vital even if they remain unacknowledged and unappreciated. The population has grown so rapidly in the last few years that it isn’t yet reflected in hard data or government policies. These good samaritans have seen precarity manifest in new forms. Many Peel residents technically have a roof over their head but have poor health because their housing is inadequate. International students are couch surfers. New immigrants live in basements. Warehouse workers sometimes just float around. At the same time, resources to help have been too stretched: three hospitals can only do so much.

That’s why places of worship and cultural organizations in Peel, with close ties to the local and global community, were the first to take COVID seriously. They came together—over big group chats, chaotic Excel spreadsheets, and long contact lists—to share their services and expertise to become Swiss Army-knives of support, ensuring that there was no wrong door for any Peel resident to knock on for help.

Dr. Hamid Slimi, the imam of Brampton’s Syeda Khadija Centre, was in Mecca for a religious pilgrimage in February when he first heard of the coronavirus. He started wearing a mask and rushed home to host a seminar with local doctors in partnership with the Peel Chinese community. By March, when the entire country went into lockdown, the mosque was ready with COVID communications for its community. Overnight, the centre’s two mental health professionals were suddenly fielding hundreds of calls each day. The mosque along with the local Muslim community started a $5 million donation campaign for Trillium Hospital in Mississauga, and collected hundreds of tons of food for local food banks, who had to eventually say it was more than they needed.

“You don’t save lives at a mosque. You save lives at a hospital,” said Hamid Slimi. “We had to support them in any way we could. Yes, the government could have done more sooner, but this was the role our community and our centre has played for years. We couldn’t wait to help our neighbours.”

The same spirit was adopted by the World Sikh Organization, which made an immediate pivot in their services to set up a drive-through langar (a free vegetarian meal) system to continue to feed a large body of international students and precarious workers. The numbers visiting Brampton’s Ontario Khalsa Darbar for food support increased from 600 a day to almost 1500 a day during the pandemic. By April, the executive team had started translating and contextualizing public health guidance for the community. The Sikh Family Helpline stepped in to help as the call volumes increased massively with people confused about the restrictions, testing, and vaccines. The WSO started contact tracing for public health, who didn’t understand how the pandemic could spread in their multigenerational communities. They even ordered special PPE for those who wore turbans or hijabs to ensure they were protected.

“A part of me understands that when the pandemic started, no one had the capacity to do any of this,” said Balpreet Singh, WSO’s spokesperson. “But by the second wave, the community engagement should’ve been two ways.”

It wasn’t. It was the WSO that pushed for a pop-up vaccine clinic to be set up at the Brampton Gurdwara because they knew that the community felt safe there. It is WSO that is still fielding 30 calls a day to ask if that vaccine clinic, which has since ended, can still be accessed or how second dose appointments can be booked.

“There are gaps that continue to exist that we just cannot fill,” Singh said.

“Peel’s inequities were ignored so it put a lot of pressure on us to fill in those gaps… The onus was on us to make things better.”

In May, Manvir Bhangu, the manager of operations for Punjabi Community Health Services (PCHS) was helping to set up a pop-up clinic in Brampton’s South Fletcher’s Sportsplex. She and a team of five volunteers knocked on every door in the neighbourhood and visited every gas station and small shop to sign up people on the spot. “We’d tell them that their appointment was tomorrow, right across the street,” Bhangu said. “That’s the kind of approach you have to take to help your community when they don’t have the luxury to sit online in a virtual line. ”

Bhangu, 29, joined PCHS last July in an effort to be proactive. She works 13-hour days, seven days a week, trying to meet the demand for all of PCHS’s services, from mental health, which has had a waitlist since the pandemic started, to gender-based supports. PCHS, with its 100 paid and short-term staff and dozens of volunteers, couldn’t provide everything and was already stretched for resources. So it partnered with anyone willing to work with them: online, multilingual tutoring services providers, local taxi companies, financial aid services. Everyone from businesses to grassroots groups. Wherever the organization was needed, they were there. Bhangu would prepare overnight or with an hour’s notice and show up.

“Peel’s inequities were ignored so it put a lot of pressure on us to fill in those gaps,” Bhangu said. “We wanted to create a network as large as possible to support the community. The onus was on us to make things better. We were doing it all on the ground with as much manpower we had, which is not as much as the government.”

But the government offered no catered response or quick thinking. “The government was so far removed from what was happening in Peel,” she said. “We had to step in to provide the cultural lens and ensure the community was being taken care of the way they needed.”

Bhangu wasn’t alone in feeling this way.

Jaspreet Singh, an international student who graduated from Sheridan College in 2019 and the founder of the International Sikh Students Association, has spent his days working as technician for essential workplaces and his nights and weekends helping Peel’s large international student community—students who had moved to Canada just as the borders shut down. “People don’t understand how alone these students feel right now,” he said. “They have no job, no physical classes to go to, bad housing conditions, and no official health care. All they have is me and the 20 other volunteers I work with.”

Gurpreet Malhotra, the CEO of Indus Community Service, a 35-year-old agency that helps newcomers, seniors, and other vulnerable groups across Peel, started COVID education and information programs, hiring over 30 community health ambassadors. Their job was to help those who weren’t asking for it but needed it. “We were talking to immigrants who had just moved in March and didn’t have income or jobs or access to health care,” Malhotra said. “We were talking to international students who were living 10 or more to a home. These were horrible circumstances with enormous stress that we shouldn’t have dealt with alone.”

Seema Marwaha co-founded the South Asian Health Network because the government wasn’t meeting people where they are. Marwaha, a general internal medicine physician, worked in Peel for over six years and knew just how complex the community was. “The government was just slapping people in Peel on the wrist without getting to the root of the problem,” she said. “So it was left to us to do things differently.”

That was most evident when Marwaha visited a Peel pop-up clinic. Everyone she spoke to had been contacted and persuaded by PCHS or another local community organization through door knocking or email or social media.

In a post-pandemic world, Dosani hopes governments recognize and learn from the ingenuity, creativity and grassroots efforts that took place in Peel. People put their lives on hold to make everything from mental health support to vaccination clinics work the way their community needed them to work, he said, proving that collaboration could resolve health inequities “if we are willing to invest in and learn from communities.” PCHS, for example, is presently building a manual for a possible future emergency response should it ever be needed.

“I often think about a scenario in Peel where volunteers didn’t come forward or citizens didn’t go the extra mile to help their neighbour,” Dosani said. “But then that just wouldn’t be Peel. This was this community’s destiny during this time. The question is: why did it take their extra support to help Peel survive?”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.