“Can you believe it? Ramadan is going to start in April this year!” a friend of mine said back in January on a socially-distanced walk. I remember nodding, thinking about how even though we know it’s coming, Ramadan always seems to sneak upon us. Every year, like clockwork, there is a buzz about when it will begin and how Muslims plan how to adjust their daily lives around the holy month.

Ramadan is the ninth month in the Islamic calendar, following lunar phases to determine when exactly fasting commences. Everyone adjusts accordingly. Some Muslims decide to cash in a few sick or vacation days. Students game-out school finals and exams, strategizing and scheduling around the sunset.

The first pandemic Ramadan was more than a bit of an adjustment. The holiday is typically marked by large family gatherings and trips to the mosque, sometimes several a day, none which were now possible. By this year, many of us thought that we had nailed the pandemic-ification of the holy month, with small Iftar (after sunset) meals to break our fasts, and prayers at home, both only with immediate family members. But then the vaccine was announced, and a small, religious scramble began to adjust once again to a new reality.

Concerns broke out over whether or not the vaccine was halal, or if it would break one’s fast. Muslim organizations and Islamic jurisprudence institutions began communicating vaccine information, balancing the sense of urgency with acknowledging the concerns of the Muslims who depend on them for guidance.

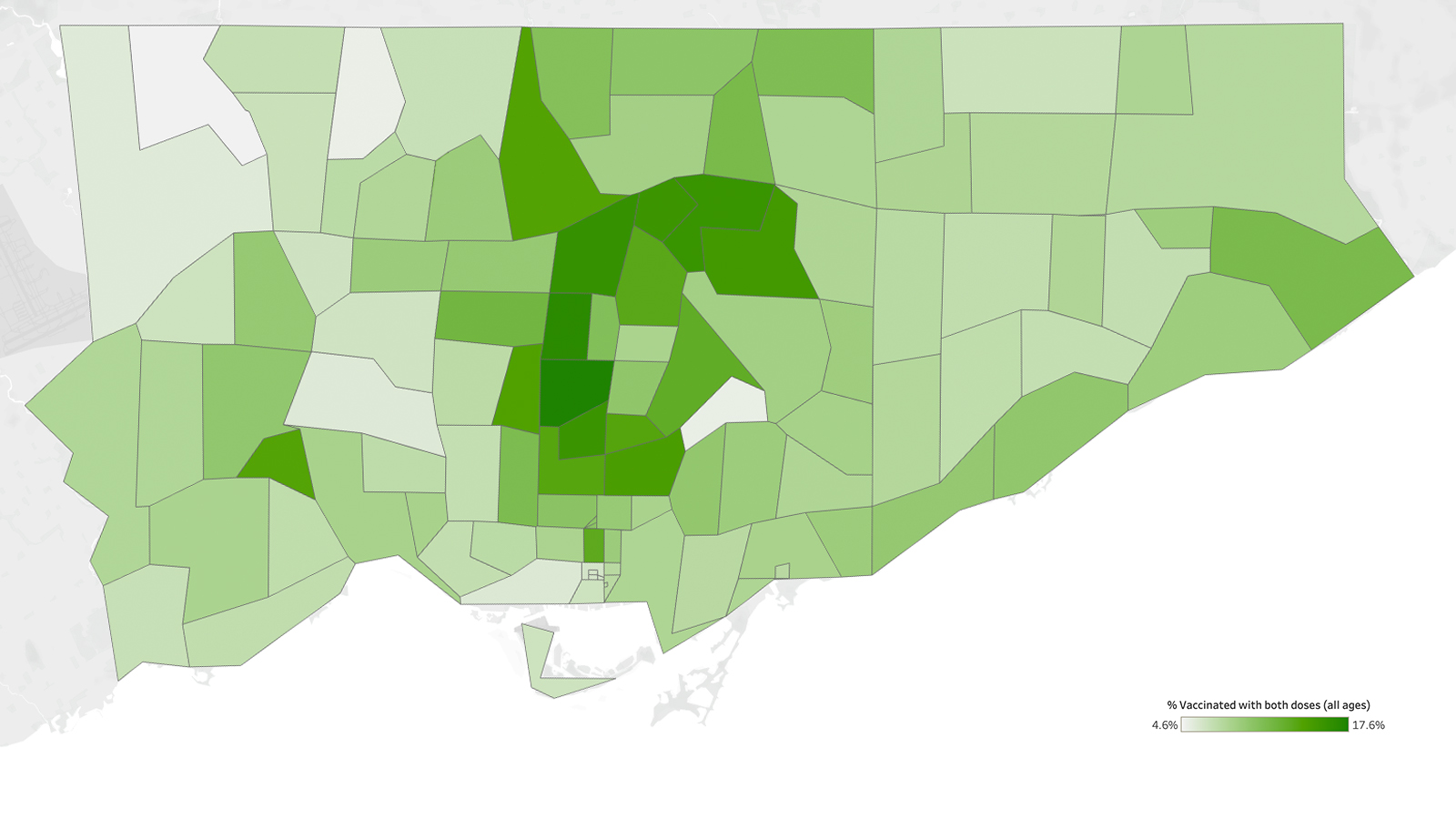

I felt this urgency in my own home in Brampton, where the vaccine rollout only picked up once Ramadan began. When I saw online that the province had announced education workers working in COVID hot spots would be prioritized, I immediately thought of my mother. She’s a schoolteacher and a woman who generally dislikes going to visit a doctor or hospital if she can avoid it. I told her she was eligible, and we waited impatiently until she received an email with a letter attached, explaining who to call. Then, two weeks into Ramadan, we sat on the phone for about an hour to book her appointment at the Paramount Fine Foods Centre in Mississauga a few days later.

Last week, I scheduled my own appointment to receive the vaccine. About two hours before Iftar I found myself standing in a reasonable line outside my Brampton neighbourhood athletic centre. It was chilly, and I passed the time scrolling through Twitter and running my thumb over the edge of my health card over and over.

There were a few other women in hijabs waiting for their vaccine as well. Afterwards, I sat waiting in the post-vaccine area; an indoor soccer field. The scoreboard read “7:15” in huge, glaring, orange numbers. Hilarious, I thought, as one of the main tips you get about surviving long Ramadan days is to try not to pay attention to the time passing. My chair was lined up beside at least ten others, in a neat row, almost mimicking the way Muslims stand for prayer together, something that we haven’t been able to do for some time now. I was in an almost-mosque, and sitting with everyone, it felt like something sacred was going on.

So much of the Islamic tradition depends on the consensus and encouragement of a collective, especially during difficult times. This explains the rush to green-light the vaccine as permissible on the part of Muslim scholars, and why I was picturing a masjid at an indoor soccer centre. It’s also probably why the recent post-Iftar vaccine pop-up clinic in Thorncliffe Park was so successful.

Ahmed Hussein, the CEO of The Neighbourhood Organization, has helped put together pop-up clinics in several neighbourhoods. When planning began for the clinic at Thorncliffe Park on May 9, he immediately thought of the neighbourhood’s Muslim population. “We were worried about people who might have a concern about getting a vaccine while they’re fasting, and maybe the inconvenience of it,” Hussein said. “We thought, maybe it’s a good idea to extend until midnight, so that people can come and get their vaccine after they complete their fasting around 8:30.”

Since the vaccine rollout began, there’s been much talk about hesitancy in different communities. I have always had this small inkling in the back of my head that perhaps some of the narratives around vaccine-hesitancy and marginalized people carry some bias. It can feel like a way to write off immigrant and Muslim communities as “backwards” or “non-compliant.” As a Muslim, I am not unfamiliar with encountering people who wish to define my experiences.

“People kept saying, and I don’t know where they get these stories, that Muslims will not be taking the vaccine, they won’t take that sort of thing,” Hussein told me. “We’re no different than any other community. We have been taking flu shots in perpetuity.” He raised his hand. “You know, I can totally show you the scars of me being vaccinated, from back home, where everybody’s a Muslim!”

As a Somali-Canadian, like me, Hussein has witnessed the power of connecting with communities on their terms on both a personal and professional level. “We put together community ambassadors who play a really critical part,” said Hussein. “People who are from the community who speak the language or belong to a cultural group, translating material and talking to people they know. We just supported them, and that really made a lot of difference.” And when this support happens, communities respond in kind.

The day of the pop-up clinic, well after sunset, Muslims were standing in line, as well as volunteering—both equally committed to making the clinic work. “I was fasting, as were a lot of my colleagues,” Hussein told me. Community members brought in food for the staff who were working and fasting for Iftar. The clinic ended up running until just after 1:00 a.m. “People were actually willing to stay as long as it took until they really finished the job.”

When I asked if the positive experiences at culturally inclusive pop-up clinics have reverberated across communities, encouraging people to get vaccinated, Hussein nodded. When communities feel cared for, they pass it on. “They influence each other,” he said. He paused. “Though, if I want to convey a message to the Somali community, I will go tell a woman,” he said with laughter, hinting at how the role of fostering a sense of community and communicating important information often falls to the moms, aunties and grandmas. If you want anything done, you must have their approval.

As he laughed, I did too. And my mind travelled to my mother’s long phone call after her vaccine with her brother in Ottawa. In different circumstances, he would have driven down one weekend and shared an Iftar meal with us. My uncle is quite a bit older than my mom, and he had concerns about whether or not the vaccine would be safe for him. As her big brother, he was giving her a small lecture, and she listened as any good younger sibling would.

My mom was in the kitchen, taking a break from preparing white rice coloured with vegetables and stew, her hand resting on her slightly sore upper left arm. The phone was on speaker, his voice filling the room, and in a way he was in my kitchen, my mom still caring for him like she had in Ramadans past. I am sure by the end of the call, she convinced him to book his appointment.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.