As of today, almost 80 percent of eligible Ontarians have received at least one dose of a COVID vaccine, with over 62 percent being fully vaccinated. But efforts to get first doses to the remaining 20 percent of the population have stalled.

In early July, Humber River Hospital’s vaccine clinic at Downsview Arena was reporting about 160 to 200 people walking in each day to get their first dose. Those walk-ins represent an important segment of the population: people who had been reluctant to get their shot, but who clearly weren’t adamantly opposed to vaccination. That’s the population that the city needs to convince in order to reach its goals for mass vaccination.

Working with Humber River Hospital, The Local created a survey to learn why these people had waited so long, and what ultimately convinced them to get vaccinated. The results reveal a number of reasons people delayed getting their vaccine and one important reason they finally got the jab: because their work made them.

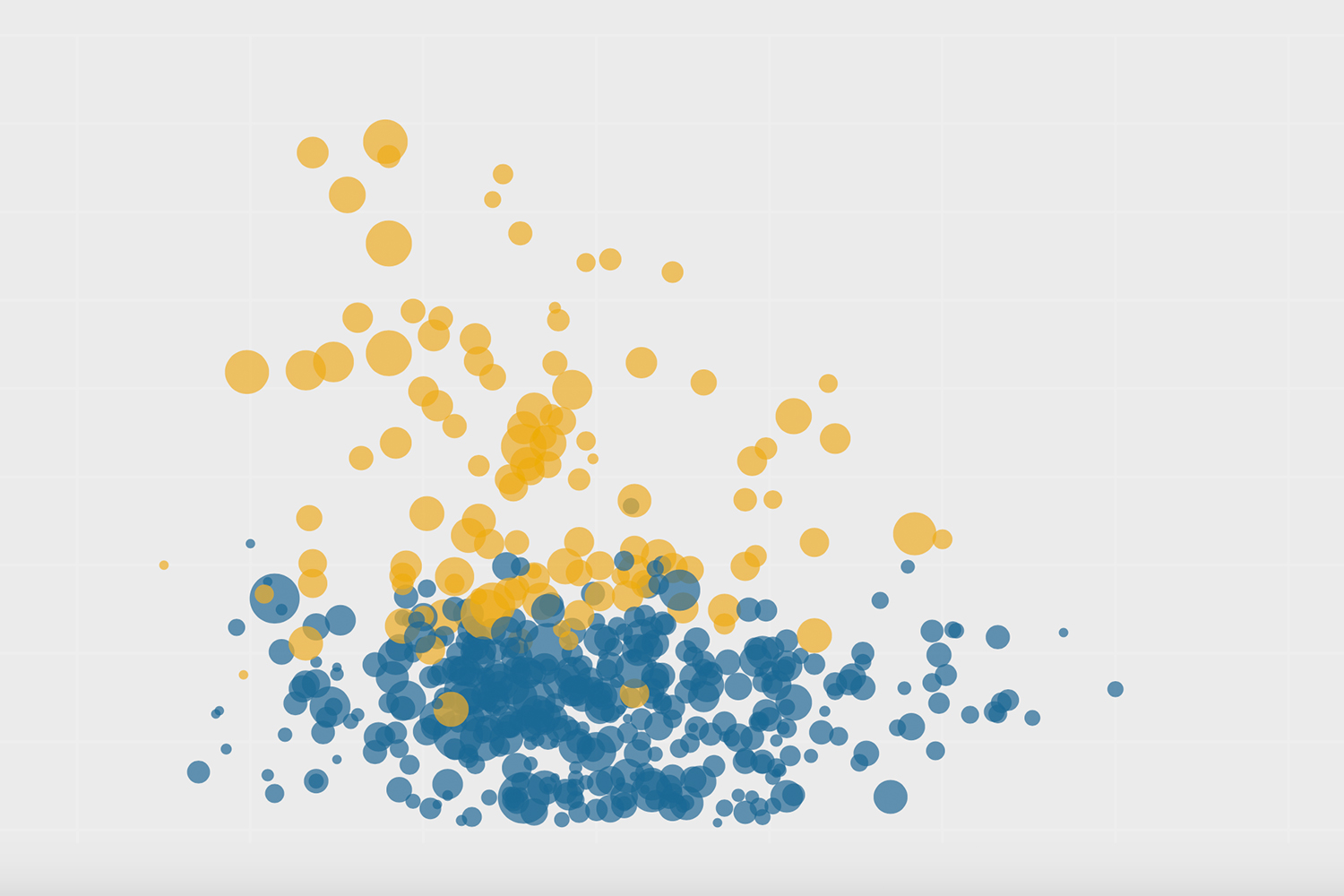

Conducted over a five-day period from July 9 – 13, the survey got responses from 389 of the 929 people who received a first dose in that time. The vast majority of respondents were under 45, with the largest group in the 25 to 34 age range. The most common reason given for why they had waited so long was fear about safety, with 43 percent of respondents reporting concerns about potential side effects, and 34 percent saying they were worried about the safety of the vaccine itself.

“They kind of wanted to bide their time a little bit,” said Sudha Kutty, vice president of strategy and external relations at Humber River Hospital. “They wanted to see those around them getting vaccinated with no adverse impact.”

“I know there were females that [had concerns] about Moderna when it came to fertility,” said Colleen Saunders, a North York resident who was at the Downsview clinic to get her first dose last week. “So I was like, ‘I don’t want Moderna.’” (There is currently no evidence to suggest that any of the COVID vaccines can impact fertility.)

Despite qualms about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, Saunders and her boyfriend opted for the shot after being advised (not required) by her employer. Her decision was also partly motivated by concerns about the possibility of vaccine passports, as well as the safety of those she comes in contact with through her job in the health care sector.

“I work with children and youth in mental health, and I don’t want to be a risk,” said Saunders.

The possibility of needing time to recuperate from the shot was also a major consideration, with 25 percent of respondents saying they just didn’t have time to get their vaccine.

“Many people can’t afford to take that time off work,” said Laura Desveaux, a behavioural scientist and member of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. “Some people have their first dose appointment booked a month from now because it was the first Friday they could find, and so they’re not worried about whether they feel ill because they’ve got the weekend to recover.”

Despite these initial misgivings, many finally took the shot because they knew people who had gotten it and hadn’t had any ill effects, or because they simply wanted to be able to get back into the world and enjoy activities with other people who had been vaccinated without fear of infecting themselves or their friends.

But the most significant factor convincing people to get vaccinated, with 35 percent of responses, was that it was a workplace requirement.

When asked why she had come to get her first dose that day, personal support worker Christabel Osarenogowu’s answer was simple: “My job.” Her employer at a seniors living facility recently announced that any staff who had yet to get their shots by the end of the month would risk having their hours drastically reduced or completely cut.

“All my residents already took their doses so I have to, because I don’t want to get them sick,” she added.

As more and more businesses and workplaces open up, a number of employers—from restaurants, to long-term care homes, to strip clubs—have begun requiring employees be fully vaccinated before they can return to work.

Last week, Seneca College became the first academic institution in Canada to mandate that both students and staff need to be fully vaccinated in order to be on campus. And vaccination centres are already seeing those students come through their doors.

“It’s really interesting to hear from a couple of students saying that their school is now requiring them to be double vaccinated to stay in residence,” said Rohan Gonsalves, director of the Downsview Arena vaccine clinic.

The results of the survey point to the effectiveness of workplace mandates. But without a universal order from the province, these workplace requirements can be a fraught issue. This week, a website designed to help customers find businesses that require vaccinations was shut down by its creator after the businesses featured received online attacks from anti-vaccination groups.

Groups like the Toronto Region Board of Trade are calling for the Ontario government to introduce a vaccine passport system for non-essential businesses, as will soon be the case in Quebec. But there is pushback from some corners, including from Doug Ford, who has said that no one in the province will be forced via government mandate to get the vaccine, including health care workers.

According to Desveaux, the percentage of the population that’s firmly opposed to vaccinations is actually very small. And for those on the fence, workplace requirements are just one added motivation.

“For those who haven’t had the devastating impacts of COVID that we often hear about in the news, what will motivate them are other aspects of their life that require them to be vaccinated in order to continue on with their life,” she said.

Desveaux says the extent to which the conversation about vaccination has become politicized has also played a role in perceptions of vaccine requirements.

“I do unfortunately think we’re going to see pushback,” she said. “But again, it’s a very small percentage that are going to view it as a fundamental infringement on their rights.”

As for the majority, including those who have been late and/or reluctant to get their first dose, Desveaux says the bigger conversation is about why this vaccine matters and how it can protect both the individual, and everyone else around them.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.