On Thursday, April 29—three weeks after nearly 75 percent of Peel was deemed a COVID hot spot in desperate need of vaccines and eight days after the region’s positivity rate climbed to a record-breaking high of 22 percent—Mississauga’s Muslim Neighbourhood Nexus (MNN) hosted the region’s first one-day pop-up clinic at its mosque.

Ayub Hamid, president of MNN, had been in talks with local and provincial health officials for a week to figure out logistics. MNN has links to a burgeoning 1,500-member community that stretched from Mississauga to Scarborough. With enough resources and support, the mosque was well-positioned to help immunize one of the most hard-hit hubs of the province. In order to do this, beyond just offering up the mosque’s space and connections, Hamid tried to help inform the region’s plans for this pop-up clinic: he asked for more days of operation, more doses, and a more targeted appointment booking system.

He didn’t get any of that. Instead, on April 26, three nights before the pop-up clinic went live, Hamid and his team were sent a location code and the phone number of the general Peel vaccine booking line with copious instructions for the mosque to send to its community: have your health card ready, call the number between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., and provide the location code to the representative. They were given just 500 doses.

At first, the instructions were only shared in a WhatsApp group between the mosque’s administration with a message to “pleeeeeease don’t forward.” Minutes later, it was circulating in other WhatsApp groups. On Tuesday morning, MNN shared the instructions to its mailing list of 1,500 people. That afternoon, local Mississauga City Councillor Sue McFadden shared it with her mailing list of thousands more.

Nakib Khan, a 35-year-old marketing manager who lives close to MNN, called in just before the line opened at 8 a.m. He was given three options for an age group or a health condition, none of which applied to him. Somehow he got through (the trick was to press zero). He was 100th in line and was told the wait would be 15 minutes. He put his phone on speaker and started working. Two and a half hours later, the music stopped playing. The phone line was so overwhelmed, it stopped working for everyone.

Khan didn’t hang up. The phone stayed silent for another hour. His group chats exploded with friends trying to dial back in, only to receive a busy tone. When the call abruptly ended, Khan attempted to call back some 80 times. Just past noon, a Peel representative picked up but she couldn’t hear him properly. Khan panicked and made a three-way call with another phone to try to fix the problem. “I literally begged her to stay on the line with me,” he said. “I tried to make her understand, this was an almost four-hour ordeal.”

Khan felt frustrated but fortunate to get an appointment. But he also felt guilty: “Peel is home to so many essential workers. They deserve it more than me and I’m not sure it’s fair that I got it because I’m a bit more tech-savvy and had time at my disposal.”

Peel region was full of such stories this past week. Those lucky to get a vaccine appointment tried unconventional methods, like getting family members abroad to call in at an early hour to beat the line. Some created an impromptu pay it forward system, where the first person to get through would also make a booking for someone else, who in turn would book for someone else, and so forth. Some took shifts, like a husband and wife who took turns watching their newborn while the other tried calling.

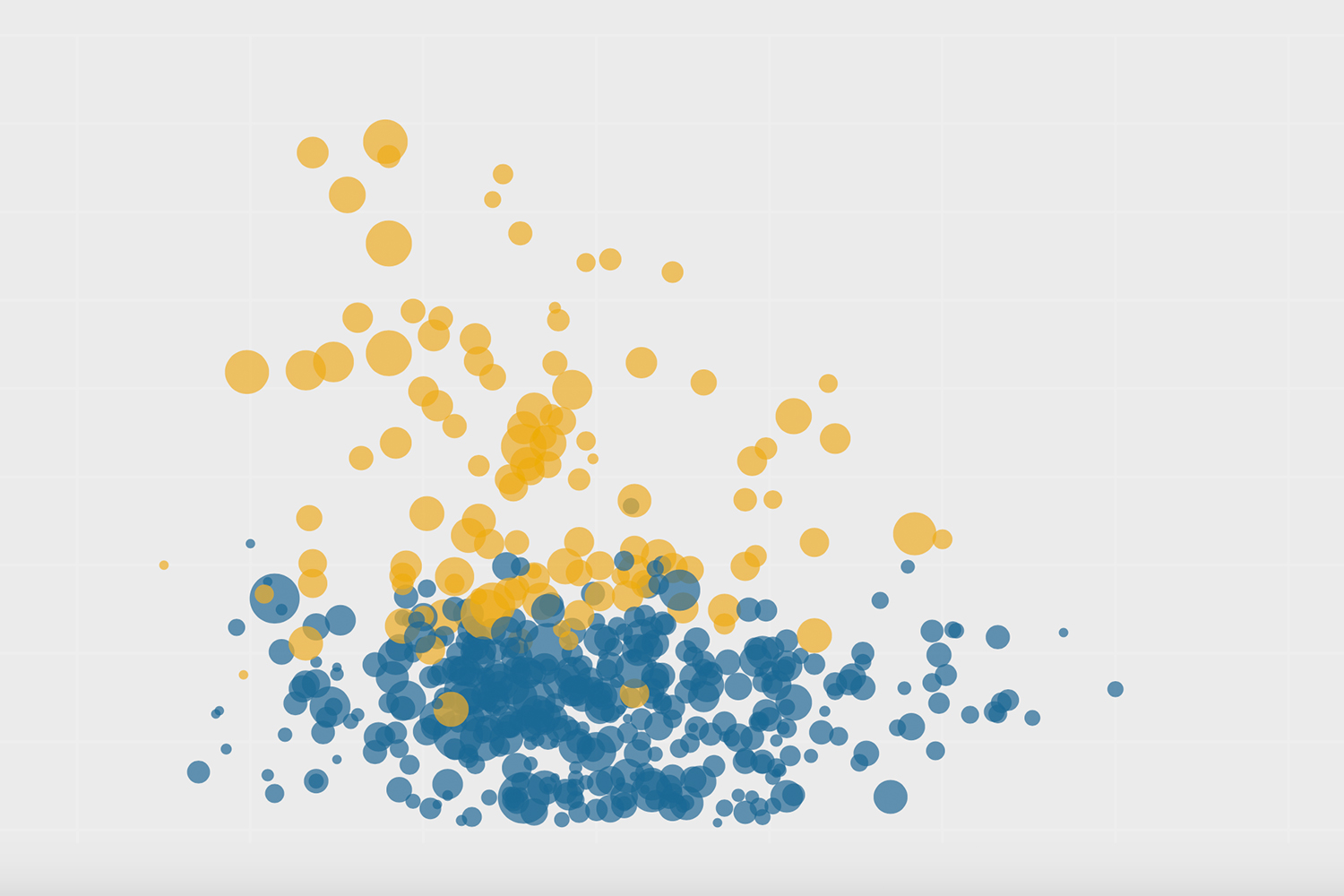

It was clear that Peel was desperate for vaccines. According to charts from Bill Comeau with data from covid19tracker.ca and the Covid-19 Canada Open Data Working Group, while Peel region (population: 1.54 million) has consistently had the highest number of new weekly COVID cases per 100,000, it has remained near the bottom in vaccine access, with smaller cities like Kingston and Sudbury sitting near the top. That is slowly changing: in the past week, Peel has climbed from 24th to 16th in the province in total doses per 100 people. That per capita number, however, doesn’t come close to truly reflecting the disparity in need for the vaccine given Peel’s extremely high infection rates.

In May, after months of pleading and begging from Peel’s mayors, local health officials, doctors and residents, the region, which sees 20 percent of Ontario’s cases despite being home to just ten percent of the population, will finally receive almost 20 percent of Ontario’s vaccine allocation. The region of Peel may have had good intentions to get these doses to its most vulnerable and marginalised populations, but the first week of vaccine rollout showed it wasn’t prepared.

“Peel did its best, but unfortunately they didn’t anticipate the pent up demand in the community,” said Hamid. “I was under the impression that they are a big organization so they must already have a good system going. It never occurred to me that we would have this kind of difficulty.”

Those who were part of setting up these clinics describe a piecemeal process that saw multiple government agencies, private companies, community advocates, and partners rushedly working together to administer vaccines. Even though these pop-up clinics had been part of Peel’s mass immunization plan since January, they were put together in a matter of days. There was no central booking system, no one copy-and-paste design for every clinic to use, and no clear, inclusive plan that would vaccinate every single Peel resident. While the community clinics are working smoothly—there are no long lines or waits—the path to get a life-saving vaccine for those most at-risk of COVID is not fair, simple, or straightforward.

“It’s a chaotic operation and everyone still doesn’t fully understand the vaccine playbook,” said one health official who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly. “In Peel, everyone’s lives are on the line and it is evident that strong systems are still not in place to protect them.”

Brian Laundry wanted Peel region’s vaccine rollout to look different from “the Toronto model,” where you set up a community clinic and invite everyone to try their chance at getting a life-saving injection while waiting in long lines.

“That simply doesn’t work in Peel,” said Laundry, the co-lead of the region’s vaccination plan.

The region’s vulnerable populations—many of whom are immigrants, international students, and essential workers—face a string of systemic difficulties in accessing health care: they can’t take too much time off work, can’t travel far away, and don’t all speak English as a first language. To vaccinate these populations, officials at Peel Public Health knew they would have to meet their most vulnerable where they are.

So when Peel announced its first set of community pop-up clinics last week, each of which was open to everyone in Peel’s 25 hotspots, it tried to structure them differently: rather than a first-come-first-serve in-person model, they tried to connect everyone to a vaccine over the phone or online.

Unlike MNN, the Muslim Association of Canada (MAC) and the Brampton Islamic Centre (BIC) were sent online forms connected to Peel’s central vaccine booking system, which were circulated widely on social media and WhatsApp. The form asked users to pick random dates and times in a calendar that didn’t indicate what slots were taken or available. The Ontario Khalsa Darbar (OKD) vaccine clinic, set up with support from Amazon Canada, also got an online form, but this one had a calendar that was updated as slots were taken.

OKD booked all 5,000 slots in one hour. A few days later, they opened a waitlist to cover any last-minute cancellations or missed appointments; they got 4,000 sign-ups within the day. MAC was able to fully book their initial 7,000 slots in two hours, but no one received a confirmation email. MAC’s standby waitlist was only open to 100 people; all slots were taken in five minutes.

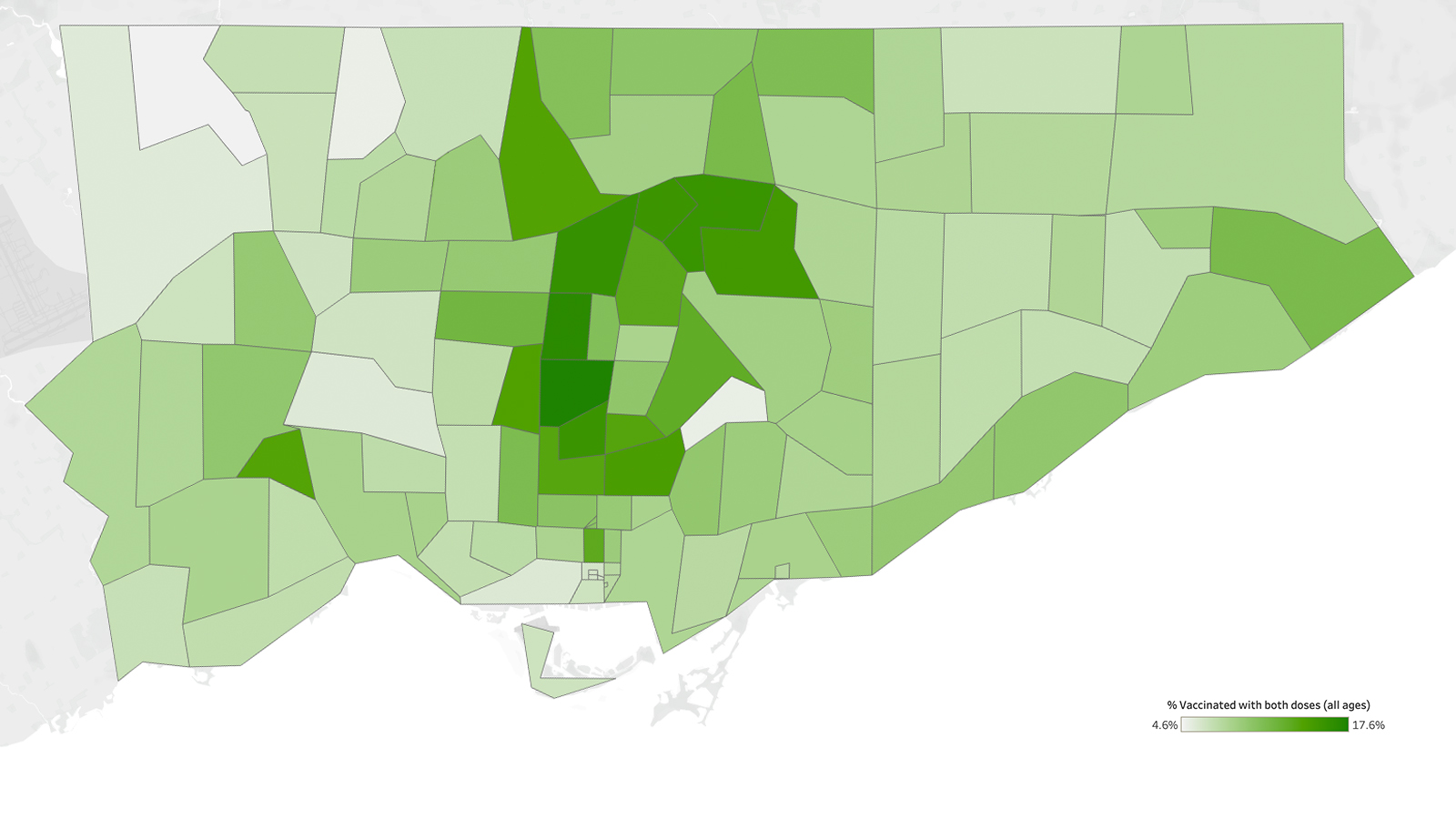

BIC, which is in the heart of L7A, one of the highest risk and most under-vaccinated postal codes in the province with less than 20 percent immunized, had anticipated the frenzy and restricted, as much as they could, who the booking link was shared with. The Brampton mosque also blocked off some 20 percent of its slots for the most vulnerable; they would be booked in partnership with local social agencies and shelters. Those who register for a vaccine appointment are also asked to bring along a non-perishable food item to support the mosque’s Ramadan food drive and/or a boxed new toy for a child for donation.

As frustrating and inequitable as this process was, there were limited options for the region’s over 1.4 million people to get vaccinated. At the moment, there are only three hospitals and one health care centre administering vaccines across Mississauga, Brampton, and the town of Caledon, which sprawls across 1,250 square kilometres. Each one is only accessible by car or public transit. The same is true for all seven mass vaccination clinics in the region.

This is why the administration of these places of worship, along with their community partners, approached Peel Public Health in February to offer their spaces for vaccine delivery. The Canadian Muslim COVID-19 Task Force, a group of Muslim doctors, faith leaders, community advocates and more, proactively led this outreach in an effort to bridge the gaps of the government’s pandemic response. Rufaida Mohammed, co-chair of the task force, said the group became “an intermediary” between public health officials and the community, making connections to local sites that could become clinics. “We have helped open the door to these groups for Peel so they could reach everyone in the hardest hit pockets,” she said. Other cultural groups did the same: a relationship with Peel Public Health was the lifeline their community needed.

“We’re running two races,” Laundry said. “One is a sprint to the frontline with the people willing to be vaccinated. The other race is a marathon: the race to get the last person vaccinated.”

“I keep saying this: just because you build a vaccine clinic doesn’t necessarily mean they will all come,” Laundry added. “In fact, if you build it, maybe half of them will come.”

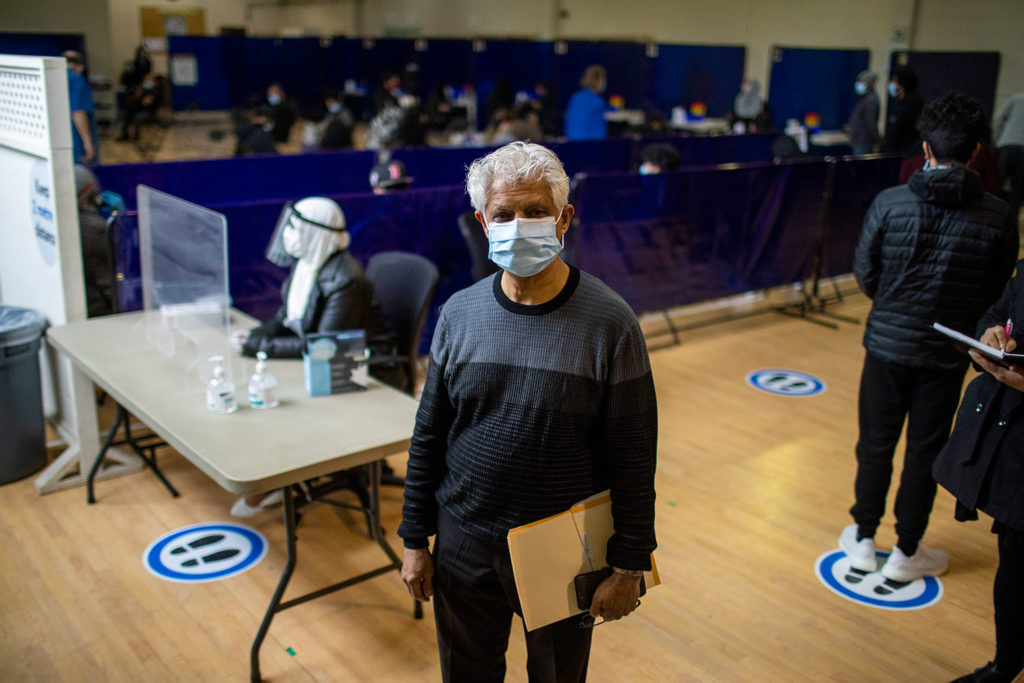

Jaskaran Sandhu felt a sense of awe when he walked into the Ontario Khalsa Darbar (OKD) for the first time in a year. The place of worship, like all others, had largely remained closed since the pandemic began. Now people were unpacking a series of deliveries via Amazon drivers and setting up tables, chairs, barriers, and signage in preparation for a vaccine clinic on May 4 in the gurudwara’s event space.

“It felt special to have this space open again for the benefit of everyone to get through the pandemic,” said Sandhu, the co-lead of OKD’s vaccine clinic. “For the first time in a while, there was true hope and happiness.”

The feeling is shared by all four places of worship across Peel that have become makeship vaccine clinics in the last few days. These spaces have ties to large groups of people that trust them. When the pandemic began, that trust became more important: even though they were shuttered, places of worship provided guidance from a distance on everything from masking to social support in multiple languages across multiple mediums.

“Everyone in our community knows of somebody who has been infected and died from this virus,” said BIC’s Muntaz Alli. “Even if we can’t open this space for prayers, we want to do whatever we can to protect the community.”

Peel region says they’re trying to get to everyone. They’ve already gone into 140 congregate settings, including retirement homes, shelters, and jails. The region’s four mass vaccination clinics are now working like clockwork, according to Laundry, giving local public health officials time to devote more attention to mobile and community clinics. Then, two weeks ago, the Ontario government gave Peel some support to set up workplace and community clinics: the province directed a third-party provider to help with the planning and logistical set-up. For Ontario Khalsa Darbar, for example, that third-party provider is Amazon Canada. (Neither Peel or Amazon Canada responded by the time of publication to The Local’s request for more information about this partnership.)

To help direct where community clinics needed to be set up, Peel’s immunization strategy established a Community Response Table, which includes over 90 local community partners and agencies and faith groups. The region started with a pilot vaccine program for around 1,000 special education teachers on April 24 and 25 to quickly see what worked and what didn’t. Then as more doses started arriving in Peel, they approached community groups with tight timelines to set up targeted clinics. The four places of worship were given between seven and nine days to set up.

In that time, BIC’s Muntaz Alli said the mosque recruited dozens of volunteers to help with traffic flow and rapid outreach. Three days before launch, the mosque was sent tables, chairs and partitions. Two days before launch, the mosque received a fridge with vaccines, along with a security officer, and what Alli called “a clinic in a box” with all the equipment needed to administer vaccines. A day before launch, they had a trial run.

This logistical process is unique to Peel. The nature of transmission and the community it is hitting is different here, with most cases starting in workplaces and spreading to multigenerational households and the larger community. That kind of spread couldn’t be handled with “the cookie-cutter approach” the province was advising all public health units to use, Mohammed said. Peel needed something more novel and innovative. It needed all hands on deck.

“Unfortunately, while we may have perfected how Peel’s community clinics operate, we didn’t do enough to bring the hardest-hit people to them,” said one clinic volunteer who was not authorized to speak. “If we’re not doing that, what’s the point of a community clinic?”

The stark proof of this disparity was the hijab-clad woman who was directing people to registration at the entryway of MNN. Shagufta Zia, a worker at Amazon, had taken the day off work, unpaid, to volunteer at the community clinic because “helping to protect my community was important.” She still hasn’t been vaccinated and didn’t have a booking at the clinic.

While it’s only been a few days since these clinics were set up, health experts and residents have already identified mistakes. Why were all of Peel’s hot-spot postal codes eligible at all four community clinics? Why weren’t they restricted to the postal code these clinics are situated in? Was there a way to stop the sign-up links being sent to everyone on every platform? Why wasn’t there a separate booking phone line for community clinics? Peel avoided Toronto’s long line ups, but were its clinics any more equitable?

“We can get better, we can always get better,” Laundry said, when asked these questions.“It’s hard to do everything at once and we were doing a lot of things at the same time.”

With vaccine supply on the rise, Peel’s vaccine administration is also increasing. “Our goal is to be the first health unit to get to 75 percent in the next five weeks,” Laundry said. Peel Public Health has asked the province to designate the entire region as a hot spot to facilitate this, while the region’s mayors are begging for more vaccines to be sent to local pharmacies. On Sunday, the province announced that anyone over 18 in one of the province’s hotspot postal codes, which includes most of Peel, will be able to sign up for a vaccine.

Community leaders and residents question how this will help vaccinate the Peel population if there’s no clear community clinic plan and booking system that will reach the region’s most precarious workers and international students. The past week has only increased the level of frustration in Peel, which has already faced neglect in the wider provincial response to every stage of the pandemic.

“It feels like Peel is overwhelmed,” said Sheikh Zahir Bacchus, head of the Brampton Imams Group and member of the Canadian Muslim COVID-19 Task Force. “They knew that vaccination clinics beyond hospitals were going to be needed; if that was the case, I believe they had sufficient time to create a better system.”

“I actually believe the mosques would’ve done a better job of handling the vaccine process,” Khan said. When the pandemic limited the number of people who could go to places of worship, mosques like MNN built apps to allow people to book one of the limited spots for the three Friday prayers, providing those who were successful with a QR code that was checked on entry. “MNN is run by a bunch of accountants and engineers. They could have figured out a much more efficient system to book people. They already have.”

Most people are in agreement with Khan: if places of worship and community centres chosen to be pop-up clinics were allowed to have more involvement in the planning process, vaccine administration may have started earlier and been more effective, and some of the very avoidable mistakes could have been prevented.

“Community groups have been adamant from day one that governments of all levels bring the table to us and harness the networks and power and goodwill we have to ensure our communities are taken care of,” Sandhu said. “While we’re grateful that the region of Peel worked with us to set up these clinics so quickly, this pandemic proves just how important inclusive public health is and what it should look like.”

In the meantime, all of these community leaders are also pondering the larger question of what happens in three or four months when it’s time for everyone’s second vaccine shot. Will these community clinics be set up again?

“I hesitate to say Peel has a plan,” Bacchus said.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.