If you had told me, years ago, that one day there’d be a pandemic and governments would have to allocate life-saving resources to various parts of the province and city, I’d have guessed, based on lived experience, that Malvern would be one of the places left behind.

Turns out, I’d be right.

Located in the northeast corner of Scarborough, bordering Pickering to the east and Markham to the north, Malvern has been hit hard by the pandemic—it’s also been home for most of my life.

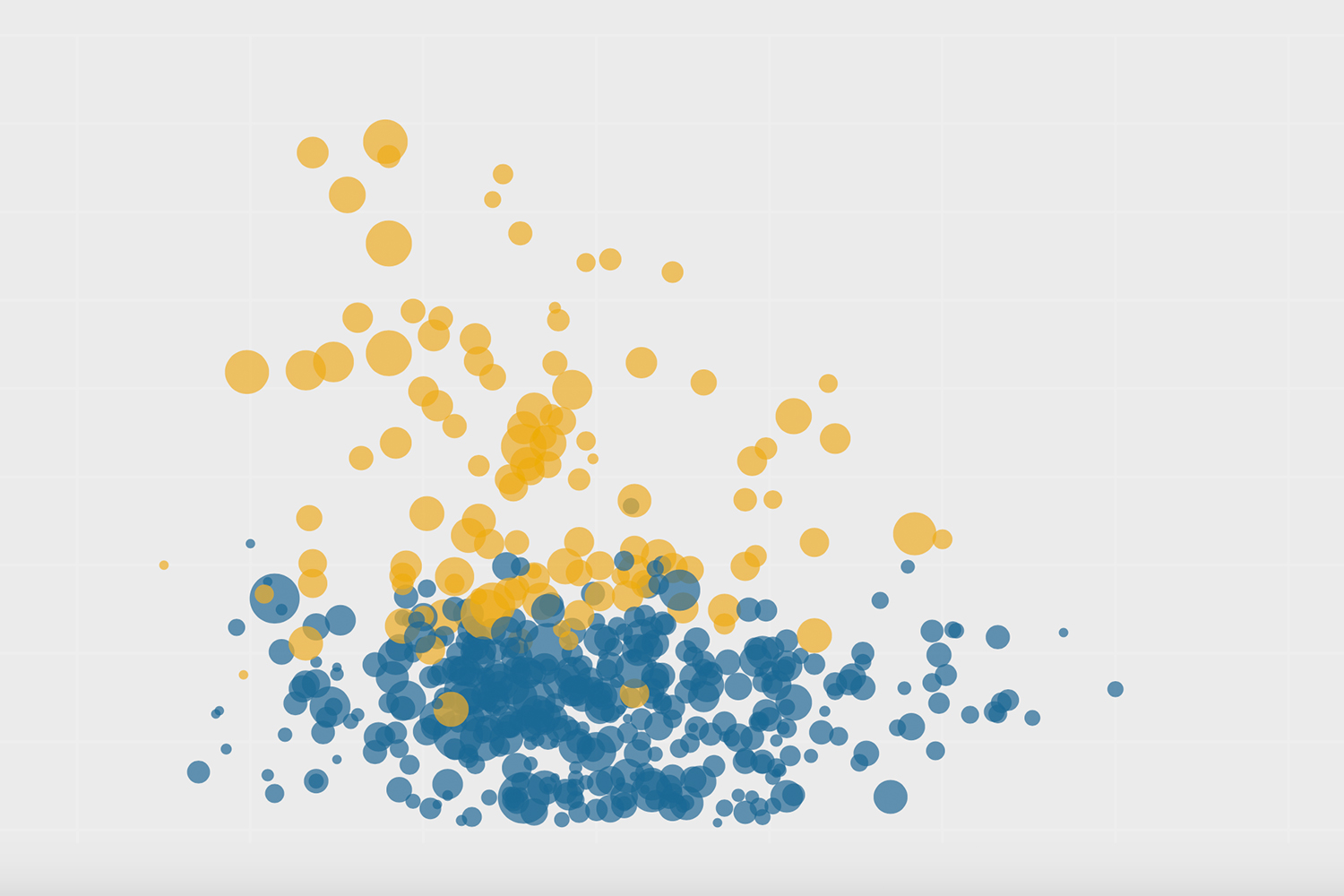

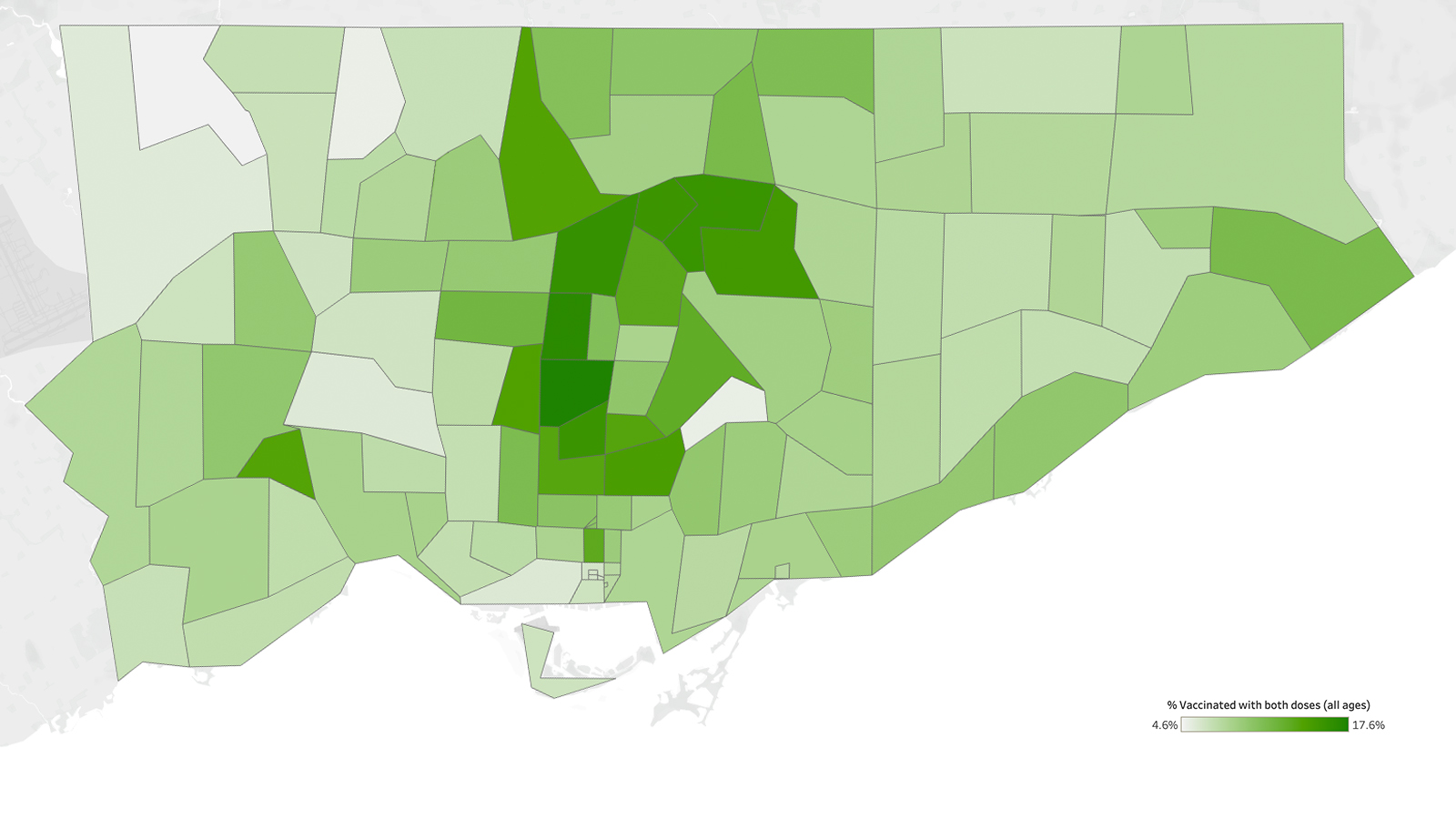

M1B, Malvern’s postal code, is a massive hot spot—a neighbourhood of 66,000 that has, for the most part, flown under the radar. The community has some of the lowest vaccination rates in the city. Toronto’s sole Amazon fulfilment centre, located right outside the city’s designation of Malvern but considered by some to be part of the neighbourhood, has 38 COVID cases and counting—the city’s largest active workplace breakout. When the province announced the hot spot postal codes most in need of vaccination, 15 of them were in Scarborough. But while media attention and pop-up clinics find their way to other corners of the city, it feels (like usual) that Malvern is being left behind.

The fact that this neighbourhood was vulnerable should have been obvious from the beginning. Like much of Scarborough, the area is primarily made up of working-class immigrants. Nearly 90 percent of residents are racialized, primarily Black and South Asian, and it’s home to a large population of the city’s essential workers. A recent study by Scarborough researchers found that the places most likely to be devastated by COVID are multi-generational households. The neighbourhood of Rouge, bordering Malvern, has Toronto’s largest proportion of households with five or more people. Malvern ranks fourth. With the majority of Malvern’s population being within working age and many contributing financially to larger households, adhering to stay-at-home orders without paid sick leave means staying safe is a nearly impossible task.

Unsurprisingly, Malvern has had some of the highest reported positivity rates in the city, currently at over 20 percent. Despite all this, the neighbourhood has seen an incredibly slow rollout of pop-ups and mobile vaccination clinics.

Around here, Scarborough Health Network (SHN) is responsible for distributing vaccines provided by the province to mass immunization clinics. One of these clinics, Taibu Community Health Centre, is in Malvern. After Doug Ford’s initial announcement early April about the province expanding vaccines to people over 18 in hot spots, Taibu was very briefly one of the clinics vaccinating Malvern adults. That was short lived, with SHN’s mass sites abruptly shutting down on April 14, followed by SHN-supplied clinics like Taibu closing their doors on April 21 due to shortage of vaccine supply.

Some Scarborough doctors have been vocal online about the challenges they face in receiving supply from the municipal and provincial government. Lisa Salamon-Switzman, a doctor with SHN, tweeted during the vaccine site closures that she doesn’t understand why Toronto Public Health and Ford’s provincial government won’t direct vaccines to high risk populations.

I was able to get my elderly parents vaccine appointments because I work from home and I’m plugged in constantly as part of my job. For many local households, however, access to the internet and personal devices is lacking. And in a community where nearly half of residents speak English as a second language, you have to wonder whether messaging about vaccine safety and supply are reaching those who need to hear it the most.

Residents here are used to feeling ignored. An article by Scarborough reporter Mike Adler earlier this year described how many of the care packages distributed at Francois’ No Frills in the heart of Malvern were turned down by customers suspicious that authorities were trying to smooth things over after their mismanagement of the virus. Anyone who grew up here can confirm: there is a palpable mistrust of the government. From the affordable housing crisis, food insecurity, and transit issues over the decades, you really can’t blame residents for their suspicion.

In the last week, the Ontario government has made belated changes that should allow more of Malvern to access vaccines, increasing the supply to hot spots and opening up registration to anyone over 18.

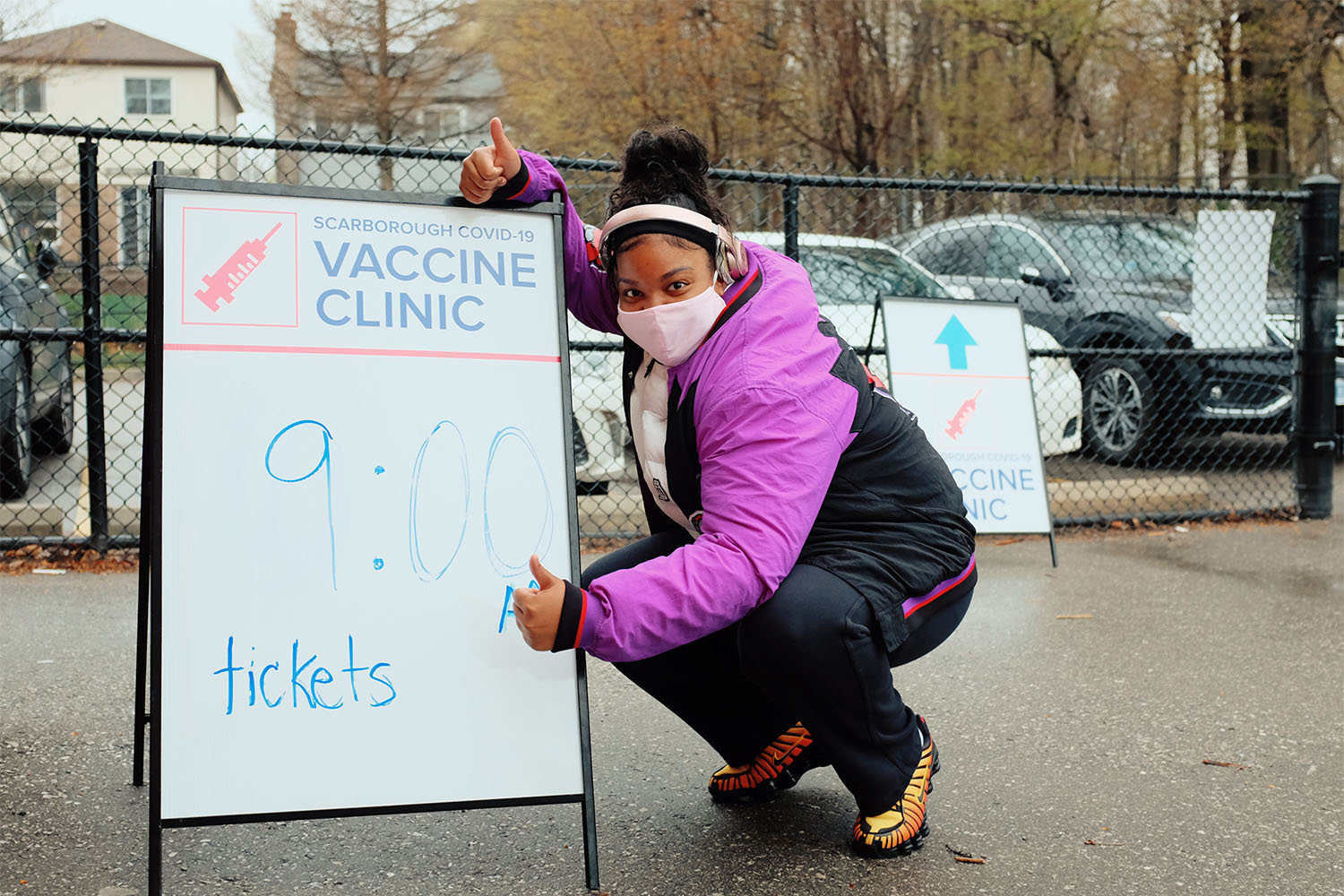

Just today, a pop-up clinic at St. Florence Catholic School opened for residents of M1B—almost a month after Malvern was first declared a priority hot spot. Slowly we inch towards getting more residents vaccinated. But the oversights during this pandemic can’t be forgotten. This past year has only cemented what long-time residents of Malvern and Scarborough have long feared: when it comes down to it, our lives will not be prioritized.

Malvern isn’t the only neighbourhood that faces structural barriers and racism—discrimination exists in all parts of the city and province. But it doesn’t need to be this way. And while grassroots organizations and community groups work tirelessly to chip away at inequities, our elected officials need to be louder and do more to save lives.

As circumstances change quickly, I wait with bated breath to see how Malvern will fare in the coming weeks. And as gears eventually shift into pandemic recovery, I fear for so many of our residents who live in co-ops, social housing, and multi-generational dwellings where the primary breadwinner has lost their job—all people who haven’t historically been prioritized.

Filled with vibrant communities and people who often get the short end of the stick, this neighbourhood deserves better. We deserve to be acknowledged; we deserve to be heard; we deserve to be fiercely advocated for. We always have. I hope, with all my heart, we get what we deserve.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.