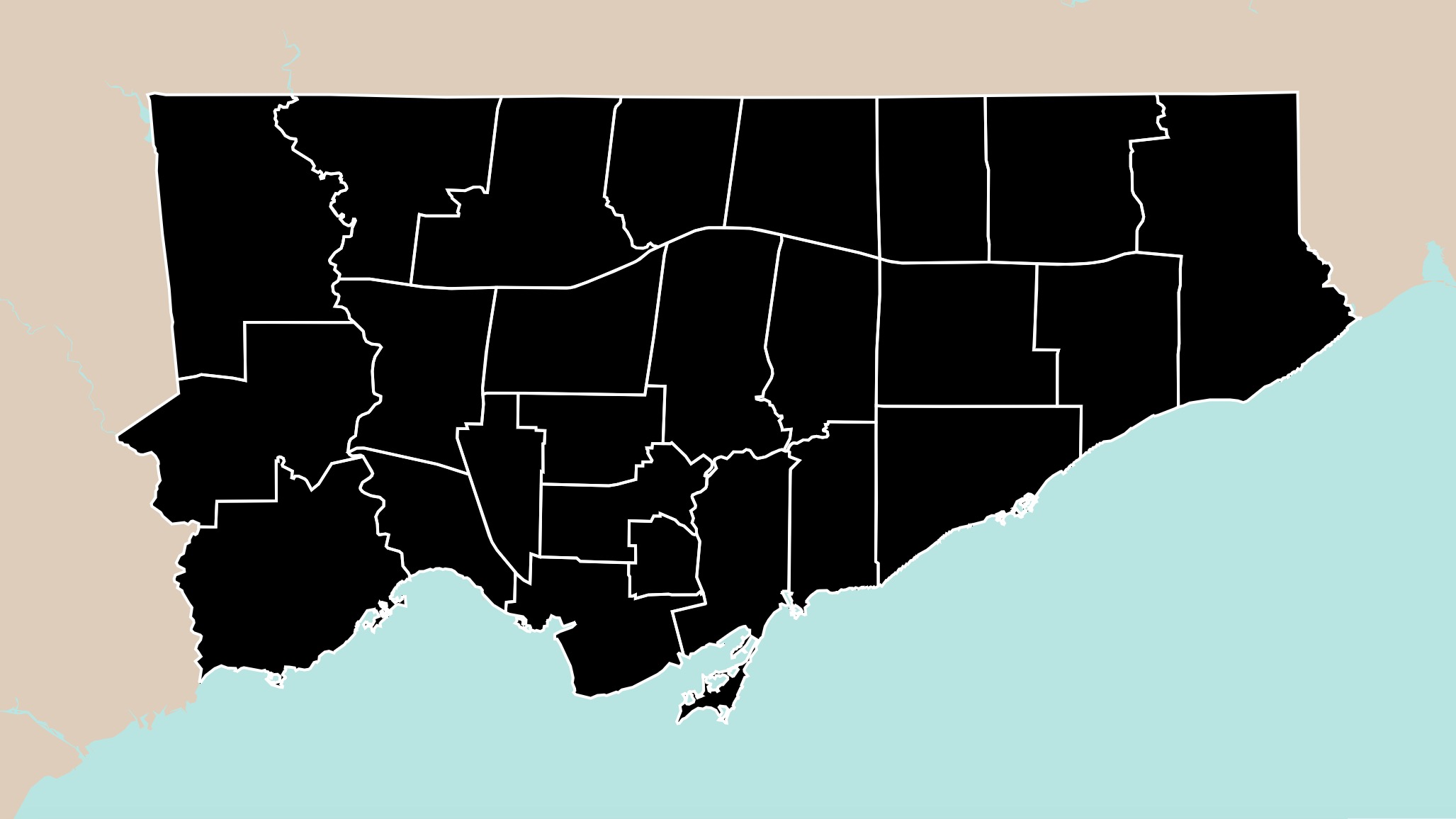

Tucked away in the northwest corner of the city, Ward 1 — Etobicoke North is Ford country. It’s premier Doug Ford’s current provincial seat, the place where the family holds the famous Ford Fest, and the ward where the job as city councillor has been passed down from Ford to Ford for 22 years—from Rob to Doug to Michael.

Etobicoke North is also a culturally and economically diverse community. Situated west of the Humber River, north of Highway 401, south of Steeles Avenue, and east of Highway 427, the ward includes Rexdale, Mt. Olive, Jamestown, Kipling Heights, Thistletown, and many more neighbourhoods. It has residents from across the world, many of them struggling and facing the challenges that come from living in a lower income community on the periphery of the city—poor transit with long wait-times, badly maintained infrastructure, gun violence, a lack of parks, and a number of other growing health and social issues.

With Michael Ford’s election to Queen’s Park to serve with his uncle, he leaves the seat up for grabs in the upcoming Toronto election. There are a total of 16 candidates seeking to fill the vacuum. While no one from the family is running, there is a former councillor and a known Ford ally who’s trying to make a comeback, Vincent Crisanti. Joining him in the race are Abraham Abbey, Bill Britton, Subhash Chand, Alistair Courtney, Michelle Garcia, John Genser, Avtar Minhas, Dev Narang, Christopher Noor, Charles Ozzoude, Donald Pell, Kristian Santos, Ricardo Santos, Mohit Sharma, and Keith Stephen—16 candidates in total, the largest slate in any ward in Toronto.

That means that from now until election day, residents in the ward have a choice to make. Will they choose a former politician and Ford ally as their councillor? Or will they elect a new voice to speak for their needs?

See All Ward 1 Candidates

Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked biographies of all Ward 1 council and trustee candidates.

Candidate Charles Ozzoude hopes the community chooses a fresh face. The 29-year-old health researcher is a long-time resident of the ward. He remembers commuting to the University of Toronto downtown and feeling the massive difference between his neighbourhood and others across the city. “It allowed me to get a sense of the disparity in development between Etobicoke North and downtown,” he says.

Ozzoude says he wants to improve public transit in the ward, as well as community infrastructure. It’s his first time running for any political office, and he’s just learning about the challenges of running a political campaign in Ford country.

“I’m not fazed by it,” he says. He recognizes there is an uphill climb facing off against candidates who may have held office or run campaigns before, or simply have more money and fundraising acumen. Former councillor Vincent Crisanti, Ozzoude says, “has an entire machinery behind him,” not to mention name recognition.

Ozzoude says he’s faced his fair share of challenges in fundraising, gathering volunteers, and building more community connections. “But I’m really working my muscles,” he says, of spending his days campaigning door-to-door. Despite the tough campaign, he’s committed and passionate about representing the community and addressing its needs. “This community has faced longstanding neglect [from the city],” Ozzoude says. “If I get elected, I want to improve things.”

According to Vincent Crisanti, the way to bring improvement to the area is to elect someone who has the experience and has done this before. Crisanti held the ward seat from 2010 to 2018 (before losing to Michael Ford when Wards 1 and 2 merged) and worked alongside the Fords and also Mayor John Tory during a short tenure as deputy mayor.

Crisanti’s proud of his record—his time in office even before the Ford era has helped him solidify a presence in the community. “Public service is the highest calling for me, I’m very passionate about it,” he says. He said soon after Michael Ford was elected to Queen’s Park, he began receiving calls from residents asking him to run for councillor again. “I’m very well known in the community,” he says. “People know me for excellent customer service for getting back to them and getting things done in a timely manner.”

He wants to tackle several issues on day one—crime, street racing, and more investment in infrastructure. But the other reason he chose to run is how he felt after seeing the list of candidates. Crisanti believes the current candidates lack the proper experience necessary for the role. While he encourages political participation, he wants candidates to “run for the right reasons” and to understand what to expect at city council.

“This is an important job, it’s a job where experience really, really matters,” Crisanti says. “I’ve got good relationships at city hall, at the province, people know me for getting things done.”

When it comes to experience, councillor candidates aren’t lacking. Dev Narang says he’s got it in spades. He’s an engineer by profession, a writer and activist by passion. He’s lived in five different countries running companies and businesses in all of them. Now, Narang wants to focus on bringing local change through politics.

“If you want to bring real change in communities, it’s important to be actively involved in the political process,” he says.

While Crisanti and Ozzoude have lived in the ward most of their lives, Narang only moved in two years ago. The first thing he noticed was the lack of maintenance in the infrastructure, amenities, and parks. Since then he’s wanted to know why the city hasn’t invested more money in the community.

“When I go down to Etobicoke Centre or downtown, it’s hugely different,” he says, comparing the level of investment. It’s also a major point he’s hearing from residents as he goes door-to-door campaigning.

Narang is aware that he’s in the most competitive race in the city, but that doesn’t deter him—he says it’s time for a change. “I am standing to make a statement that it’s time for people to speak out and that politicians cannot take us for granted,” Narang says.

The ward is heavily populated with visible minorities. In fact, it’s a “visible-minority majority” community, Narang says. And he says too often communities like this are treated as “vote banks,” with politicians only showing up during election season.

But not Rob Ford. Like so many in the community, Narang has great respect for the late mayor and councillor. Rob Ford was accessible by a phone call and was quick to action, Narang says. But since then, Doug, Michael, and even Crisanti have failed to impress him.

“Just electing people on the basis of name recognition is not enough,” he said. “It’s time to take it seriously and consider expertise.”

Narang says he’ll be available to everyone, echoing the successful Ford strategy. He wants to ensure infrastructure and parks are well-maintained. He wants to be a transit champion and ultimately ensure that Etobicoke North is “not a neglected community anymore.”

While the high number of passionate candidates might indicate that Etobicoke North is a politically active ward, voter turnout paints a different picture. In the 2018 Toronto election, just 35 percent of eligible voters came to the polls.

But the truth is the ward is politically active, just at the grassroots level. At the Rexdale Community Hub, the North Etobicoke Resident Council meets every month to discuss local issues and events. The residents frequenting the hub are “people that we normally don’t hear from,” says Warda Sharmeen, a team member at the hub who helps organize community meetings. Residents gather to discuss politics. Community leaders connect with each other to find solutions to issues from potholes to affordability.

But some of that problem solving requires the involvement of the city, and therefore the city councillor representing Etobicoke North. That’s why Sharmeen is paying close attention to this election. She prays that whoever is elected is involved in the community at that grassroots level. It’s a mobilized community that cares about each other, she explains, but their frustration emerges when they don’t receive cooperation from their councillor.

In preparation for the election, the Hub is conducting voter engagement workshops, inviting candidates to present their platforms. Sharmeen hopes that events like this can help increase civic engagement, and ultimately send more voters to the polls.

For some residents who are politically engaged, however, optimism is difficult to muster. Terrence Rodriguez works at the Rexdale Community Health Centre. He was born and raised in Rexdale, and he’s been working there for the last 15 years. During the pandemic, he saw many of the community’s inequities heighten.

“My perspective, like a lot of folks, is really just choosing the lesser of two evils,” he says of the upcoming election. The socioeconomic barriers he witnessed in his work with testing and vaccine clinics are similar to those that determine voter turnout. Families with children, working multiple jobs, reliant on public transit, have several more hoops to jump through than those affluent residents who have the time and money to go to the vaccine clinics or polling stations.

But it’s not just geographic accessibility, it’s racism too, Rodriguez says. “I’ve worked at voting polls, and I’ve witnessed supervisors being racist,” Rodriguez says, noting that incidents like that can discourage racialized residents to come out and vote.

Munira Abukar ran as a councillor candidate against Rob Ford in 2014. It taught her how strong the Fords’ hold on the community was and how challenging it was to run for office. Twenty years of Ford dominance has led Abukar to nickname Etobicoke North the “Ford ward.”

Like Rodriguez, Abukar says she witnessed racism from staff at the polls. Additionally, when she ran in 2014, her young, Black campaign volunteers often faced resistance when campaigning in apartments. They were kicked out of buildings where they were campaigning on her behalf because of suspicious superintendents, she says.

The combination of these factors and more makes it “easier for a white man” to run for office. Without that inherent advantage, wealth, connections, or allyship with the Fords, Abukar says, commanding political influence here is a “steep, uphill battle.”

Even so, Abukar says she’s made it a personal mission to participate in elections, if not as a candidate then as a volunteer. In a ward that could have new representation for the first time in a generation, Abukar wants to be sure people like her are seen. “Since I turned 18 I’ve always attempted to work in elections,” she says. “So folks can see individuals who look like them.”