For weeks, Dr. Lawrence Loh had been looking for the Ontario government to do more.

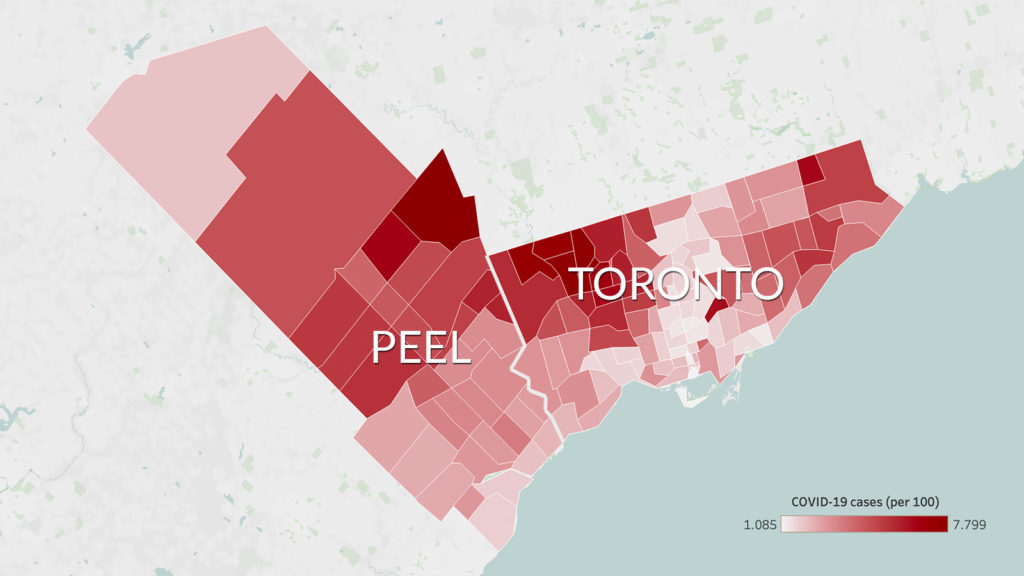

The medical officer of health for the Peel region—the territory west and northwest of Toronto that encompasses the sprawling municipalities of Brampton, Mississauga, and Caledon—had been carefully watching how the new COVID variant was spreading “further and faster” in local workplaces.

At the time, and even still, there were over 400 workplace outbreaks and 90 ongoing workplace investigations. Between September and December, 66 percent of Peel’s community outbreaks occurred in workplaces, a trend that has only continued.

Anyone tracking these numbers would come to the same troubling conclusion: “We clearly have a workplace problem,” Loh told The Local. “And the game has changed with the variants.”

That’s why on Friday, April 16, when Premier Doug Ford announced an extended two-week stay-at-home order along with playground closures and new pandemic police powers, Loh’s first thought was that these measures were not going to reduce the rapid transmission across Peel.

Three days later, on April 19, he reached out to Dr. Eileen De Villa, his Toronto counterpart, who was noticing similar transmission trends. Together, they agreed to invoke the power granted to them, known as a Section 22 order, to order all businesses with five or more COVID cases in the last two weeks to close for 10 days. “This wasn’t in response to [April 16],” Loh said. “This is what our community needed. And I have to act on behalf of the community I serve.”

That night, Loh called Dr. David Williams, Ontario’s chief medical officer of health. They spoke for 40 minutes. Loh explained what he was going to order the next morning. “Dr. Williams understood we have a workplace problem,” Loh said. “He was keen to see the outcomes of this decision.”

This is not the first time Loh has staunchly veered away from the provincial pandemic response. In fact, it’s the third time in 40 days that he’s acted alone. On March 12, he invoked his Section 22 power to shut down Brampton’s Amazon warehouse and instruct all workers to self-isolate for 14 days in the wake of an outbreak. On April 5, he ordered all Peel schools to remain closed despite provincial instructions to reopen. Each time, Loh has given the same reason: these were “necessary” steps in the face of continually rising cases. “You can be mad at me as much as you want but this is what needs to be done,” he said.

Loh has a new-found sympathy for airline pilots on a delayed flight who urge patience with smiling faces as passengers get more irate and frustrated. This is a job he was thrust into in March 2020, on the tail end of the first wave, after his predecessor stepped down. Loh started his career ten years ago as a family physician in a north-west Brampton clinic that served 1,200 people. He’s grown with the community and watched it change. He knew firsthand that Peel hospitals were at risk with each wave. He also knew there were significant health inequities in the community long before the pandemic.

“The story of Peel has always been the story of disparity,” Loh said. “Throughout the pandemic, that has been our biggest challenge.”

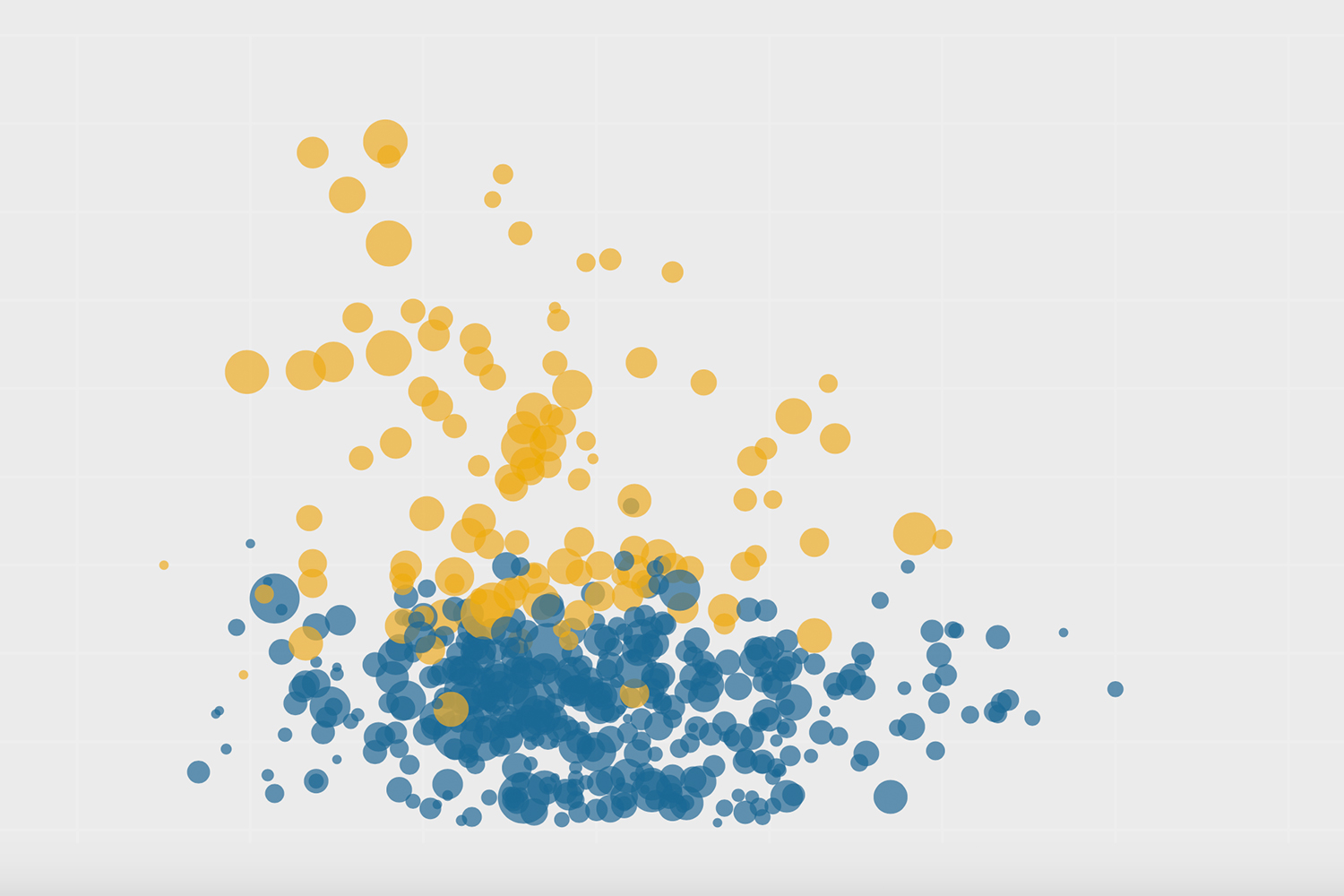

The region has been a hotspot for cases from day one. According to data from Bill Comeau and the Covid-19 Canada Open Data Working Group, Peel ranks second in the entire country on current weekly cases per 100,000 people, and fifth in total cumulative cases per 100,000 people. The test positivity rate in the region right now is above 20 per cent, more than double the provincial rate; that means that case counts don’t come near capturing the actual number of infections in these three municipalities.

There are so many reasons Peel has been so hard hit by the pandemic. The region is a complex cacophony of communities that has not been adequately assisted by the province’s one-size-fits-all pandemic response. Peel has been the fastest growing region in Ontario for decades, with the most underfunded health care system in the province: there is only one hospital in Brampton to serve over 600,000 people. It’s home to the province’s largest number of international students, new immigrants, and workers in distribution centres. Many of these people live in multigenerational homes, not just because it’s a feature of their culture, but because of their inability to afford housing and child care while working paycheque to paycheque.

The region houses some 80 percent of all companies in the Greater Toronto Area. Around 40 percent of all Amazon packages to Canada are processed here. Some 60 percent of trucking services begin here. Peel is the largest producer of everything from chicken and peanut butter to ventilators. It’s the logistics capital of Canada—a community of workers who have put themselves at risk so the rest of the country can comfortably stay at home.

All of this has set the region up for what one health care worker called “the perfect pandemic storm.” To the frustration of its residents, its mayors, and its workforce, that hasn’t been acknowledged at any point during this pandemic.

Instead, Peel has been placed under the most restrictive lockdowns (the latest one hasn’t been lifted since November 2020). As cases continue to rise, its residents have been unjustly vilified at various points, most recently at Diwali last November. While visible minorities represent 63 percent of Peel’s population, they make up 77 percent of Peel’s COVID cases, with the most cases occurring among South Asian communities.

“We’ve borne the brunt of an extremely broken system and every bad decision,” said the health care worker, who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly. “And at every step, people have looked at us and said, ‘Look at stupid Peel. They’re just a bunch of brown people who can’t take care of each other.’ Well, no one helped us or took care of us either.”

When COVID-19 first arrived in the GTA, it likely came through Peel, home to one of the largest airports in the country.

On March 16, 2020, the day before Ontario first declared a state of emergency, Gurdeep Dhillon was picking up a couple from Hong Kong at the airport. They were wearing masks; he wasn’t. Confused, he asked them if he should be wearing one too. In broken English they told him “up to you.”

The 62-year-old lives in Brampton and has been driving an airport limo for over 30 years, or what he describes as “all my life.” It’s a job he considers “a privilege and a duty.” He says he’s the first person so many travellers to Canada meet, whether on their way home or on their first visit.

In so many ways, Dhillon and his colleagues are the gateway to the entire province of Ontario.

When the pandemic hit, these drivers—all of whom live across Brampton, Mississauga, and Caledon—were among the first to get infected. To this day, Dhillon wonders where they carried the virus in those first weeks of the pandemic.

To understand why Peel was so hard hit by COVID, you have to first understand how it links to the regions surrounding it, says Omar Rais, a 29-year-old who has lived in Mississauga for over 17 years. From his home on Winston Churchill Boulevard he can drive 15 minutes south to Oakville. If he drives 15 minutes north he’ll get to Halton Hills and Brampton, where he can see the Amazon fulfillment centre. Anytime there’s a shift change, the traffic on the two-lane road comes to a complete stop as the workers head home.

“We live in a region where other regions are easily accessible to us,” he said, “and the provincial pandemic response has never once taken that into account.”

When the lockdowns started, everyone who lived or worked in Peel suddenly had very different pandemic experiences, despite living a few kilometres apart. Restaurants on one side of the intersection between Halton Hills and Mississauga would remain open, while those on the other stayed closed. Gyms in Oakville were filled with people, while those ten minutes away in Mississauga remained shuttered.

The three mayors of the Peel region knew how “seamless” travel is across their three cities and those nearby. Mississauga Mayor Bonnie Crombie told The Local that from the beginning they urged all mayors to have a consistent policy across the GTA to ensure the spread of the virus was curbed. They met virtually every Monday at noon to try to ensure consistent policies and share notes.

Brampton Mayor Patrick Brown said that this was important because while other cities became a ghost town in the first wave, Brampton was still functioning normally, with most workers still going to their jobs. Caledon Mayor Allan Thompson saw the same thing in his largely rural town, which was running rampant with cases as workers continued to move the local economy in food processing plants and distribution centres.

A recent study by the Toronto Region Board of Trade proved how essential these workers really are: 53 percent of Peel’s more than 600,000 employees needed to be on-site for work, the study found. These workers were feeding their own families as well as every other family in Canada. And this workforce grew over the course of the pandemic.

Gagandeep Kaur, an organizer at the Peel branch of the Warehouse Workers Centre, said that she’s been assisting many new employees who joined warehouses after losing their full time jobs. “Warehouses were hiring consistently,” she said. “So those laid off took these jobs to help their families. But they had no protection, no preparation, and they struggled to stay safe.”

“I never realized how dependent Canada was on these supply chain companies and their workers,” Brown said. “It was really extraordinary to learn just how interconnected Peel was with the rest of the country.”

To protect these essential workers, Brampton transit was the first public transport system in the GTA to have a mandated mask bylaw. But local efforts fell short of much-needed provincial policies like paid sick leave, which the three Peel mayors and Loh have long been requesting. “We all thought that everyone was going to be treated equally during the pandemic,” Brown said. “But this virus was not equal and fair, and Peel needed a lot more help.”

That help never came. In the first wave, Brampton (population: over 603,000) got the same amount of testing resources as Timmins (population: over 41,000), according to Brown. Meanwhile, cases in Brampton and across Peel were rising to worrying levels. Every councillor, MPP, and mayor The Local spoke to used the same analogy to describe the situation, which was first publicly stated by Brown: “If you want to put the fire out, you don’t go two houses away.”

The fire was in Peel, and it was spreading across the province from essential workplaces to multigenerational households to a sprawling community. The transmission rate was “very, very high,” Crombie said.

“It became so obvious to us: you can’t stop the spread of the virus if you don’t stop it in Peel,” Crombie said.

Unfortunately, the province’s pandemic policies didn’t consider that. If they had they would have started by giving the region what Brown said was needed most: “testing, testing, testing.” They would have begun investigations into workplaces. And they would have sent way more vaccines.

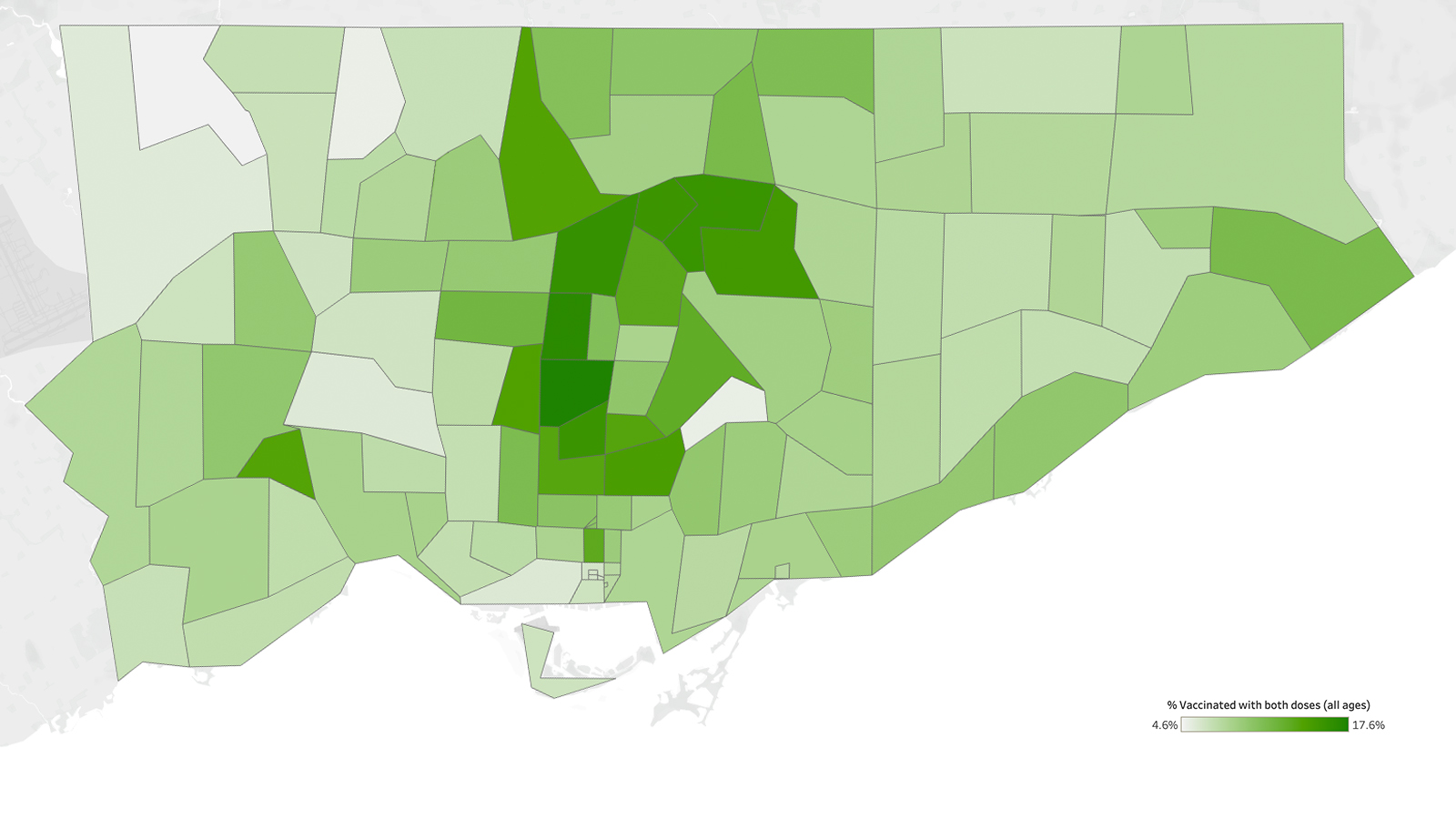

Peel currently accounts for 20 percent of all cases in Ontario, yet they’ve only received 7.5 percent of the vaccines. To date, the region has administered over 336,000 doses, which is just over a third of Toronto’s almost 980,000 administered doses. The region was not selected for the COVID pharmacy pilot program, despite having the most cases in the province. Only this week did the provincial government allow seven Shoppers Drug Mart pharmacies in Peel to offer vaccines 24 hours a day, seven days a week—a game changer for workers who cannot take time off. That’s still not enough: Brampton, for example, has eight pharmacies offering vaccines per 100,000 residents, while Kingston has 26 pharmacies catering to the same number.

Meanwhile, a recent Toronto Star report found that some of the hardest hit neighbourhoods in Peel recommended for targeted vaccination by Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table were not included in the province’s final list of hot spots. And while Mississauga and Brampton City Council have passed motions to set up mobile vaccine clinics at places of worship and low-income neighbourhoods, discussions are “moving at a snail pace” said one person part of these talks who wasn’t authorized to speak.

On April 21, Premier Ford called Brown to discuss these vaccine shortages and promised to help supply more vaccines and mobile vaccination clinics in two weeks. One doctor who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly said that in a pandemic, “two weeks is too long.” The next day, the premier broadly pledged to get vaccines to all 152 pharmacies in Peel and set up vaccine clinics in companies across the region; no timeline has been given, but mayors and healthcare workers alike are desperate for such measures now. Brown has even taken to demanding that the airport be shut down again as new, more deadly variants are detected in Peel.

At every turn, Peel has been neglected. On so many occasions, the three Peel mayors said they were taken by surprise by provincial decisions, like vaccine distribution by overnight hotspot designations or sudden school closures/reopenings, which meant that they had to scramble and field angry, confused phone calls from residents.

The cost of this neglect by the province has been great. In the first wave, Dhillon lost 10 of his colleagues at Airline Limousine to COVID. It remains the highest known count of deaths in an Ontario workplace. Dr. Amanpreet Brar, a Brampton-based medical resident, knew some of them. They were her uncles, her friends’ fathers. She remembers one of them being admitted to the ICU and dying all alone. “They lived and died the same: completely invisible,” she said.

The resentment towards these decisions has filtered down to the residents and workers of Peel, Rais said. When the vaccine bookings opened for those between 60-64 years old, Rais was confused to find that the closest clinic available for his dad was in Etobicoke. “You still had to leave the region, your neighbourhood, and go east for a jab,” he said. Meanwhile, pop-up vaccine clinics were being set up across Toronto.

“Throughout this pandemic, as a citizen of Peel, I’ve felt second to Toronto,” Rais said. “To be frank, I don’t think Doug Ford cares about Peel.”

“All levels of government failed us and let us put ourselves one inch closer to death every day.”

Structurally and institutionally, Peel has always been underfunded. The last census occurred in 2016 and since then the region has seen exponential population growth. Latest estimates suggest over 1.4 million people live here, yet the region sees the lowest per capita funding in health care. Whereas Toronto has five hospitals on one street, Brampton has one hospital, while Mississauga has two. Three months before the pandemic, Brampton City Council unanimously declared a health care emergency. Patients were dying in hallways; there weren’t enough beds for everyone.

For all these reasons and more, Peel doctors were frightened even before the pandemic hit its peak. They started surge planning at a scale never seen before by sending patients who didn’t need emergency care to hospitals across the region, some as far as Kingston. They sent away pediatric patients, those receiving therapy treatments, and others because they were already stretched too thin to care for them.

Beyond the issue of limited capacity, there was a cultural health care problem too. Peel’s large immigrant and multicultural population includes countless patients for whom English is a second language. Gaibrie Stephen, a 27-year-old ER physician in Peel, said the most heartbreaking thing he had to do was shut out caregivers that help such patients. Due to limited visitor policies, hospitals were turning to translation devices, but “that’s not the same as loved ones.”

Sirat Kaur Dhillon, a 25-year-old nurse who worked at Mississauga’s Credit Valley Hospital for the last two years, saw so many immigrant elders coming in, some of whom were visiting family members and couldn’t travel back to their home countries. They didn’t know what they were meant to do, how to self-assess their symptoms, or even how to isolate among their large families. “That was the worse part: these patients didn’t know what to advocate for and what was accessible to them in terms of medical help,” she said. “Basic information about COVID-19 was not mainstream for them because it wasn’t in their language.”

Loh said he was “challenged by all these systemic and structural inequities, which limited the extent my advice could go.” To address these inequities, Peel Public Health was the first system to go live with contract tracing. It was also the first regional health unit to set up an isolation housing system. It is headed by Dr. Naheed Dosani, who calls it “an important part of a compassionate response to a pandemic that was hurting the most vulnerable among us.” Four isolation centres have been set up across the region that offer “whole-person care” to anyone who comes in, including medical, mental, income, and social supports.

Loh was also the first regional medical officer to ask for paid sick leave in an effort to protect workers, with Ontario’s remaining health units following suit. Dosani believes Loh was able to address that because he is a racialized health care worker, and Peel Public Health Unit is largely made up of racialized people who closely understood the community they served. They knew early on the value of multilingual communications and cultural-specific policies. “Representation really mattered,” Dosani said.

These deep-seated inequities are also why Loh chose to enact stricter policies than the ones suggested by the province. Doing so was difficult. Loh said he felt “pressed” into adhering to the province’s orders, which included reopening more quickly, reducing contact tracing, and rushedly lowering the age cut off for vaccine eligibility.

In November, for instance, the provincial government pushed Peel to the red zone, which allowed businesses to reopen despite the fact the ICUs were full and cases across the region were spiralling. “I remember sitting thinking about it and looking at our rising graph and then deciding to issue a letter of instruction cancelling all weddings, social gatherings, life events until the end of the year,” Loh said. The province followed suit a few weeks later. “That was challenging because I became the bad guy for a while. But if you look at the graph, we plateaued and stayed plateaued after. I shudder to think what would have happened if we kept on that path.”

When asked to reflect on his dealings with the provincial government over the past year, Loh says just one line: “If we stuck to science and recommendations of science, things may have gone more smoothly.”

“From my perspective as a scientist, the pandemic is like a hurricane,” Loh said. “If a hurricane hits, you don’t think about reopening restaurants and gyms. You need to evacuate everyone and save lives.”

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that the pandemic has given the Peel region a reason to come together. Whether it was the mayors who worked collaboratively in an unprecedented way or the doctors who began speaking up for the patients who were too scared to say anything to their employers or their elected officials. It didn’t help that the rest of Ontario had also started to vilify the population for seemingly ignoring the rules, when all they were doing is keeping the engines of the province running.

Grassroots groups and social agencies have filled the gaps where institutions have failed to provide meaningful community engagement. Places of worship became food banks and lines of income support. Other community groups took it upon themselves to find specialized protective personal equipment for workers who wear turbans and headscarves. Local agencies hired community health ambassadors to do outreach to immigrants who had just moved as the pandemic began and didn’t have access to income or health care. Neighbours started becoming support workers and vaccine doulas for one another.

The workers and volunteers of Peel are exhausted and wary of being critical in public, but they are united in one sentiment eloquently put by a 50-year-old man who works at a food logistics warehouse in Brampton: “All levels of government failed us and let us put ourselves one inch closer to death every day.”

“Pandemics are like guided missiles that impact people who experience vulnerabilities,” Dosani said. “When we look back, we’ll look at the people of Peel and how we could’ve better protected them.”

The thought is top of mind for Loh, too. “The inequity has taken a toll on our region,” he said. “But there will be a recovery and an exit. The question is how do we continue to address the structural inequities and underlying determinants that have hurt the people in Peel. If I make it through the pandemic, that is going to be the next challenge Peel Public Health and I navigate.”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.