Every morning at 6:00 a.m., like clockwork, Toronto Mayor John Tory sends out a tweet with a flashing GIF broadcasting the city’s progress in vaccinating its residents. “1,333,283 doses administered to date,” the latest post, from Friday May 7, announced. The graphic also boasts about the number of doses at the nine city-run mass immunization clinics (MICs), combined. But nowhere on the graphic or the accompanying daily press releases does the city list the number of vaccines given at any individual MIC.

This last point has become something of a water-cooler topic within Toronto’s tight-knit vaccine community: how many doses are actually administered at each MIC? Sites like the Metro Toronto Convention Centre and the Toronto Congress Centre are flagship clinics that were supposed to lead the charge for the largest vaccination campaign in Toronto’s history. So why is the city not fully transparent about their numbers?

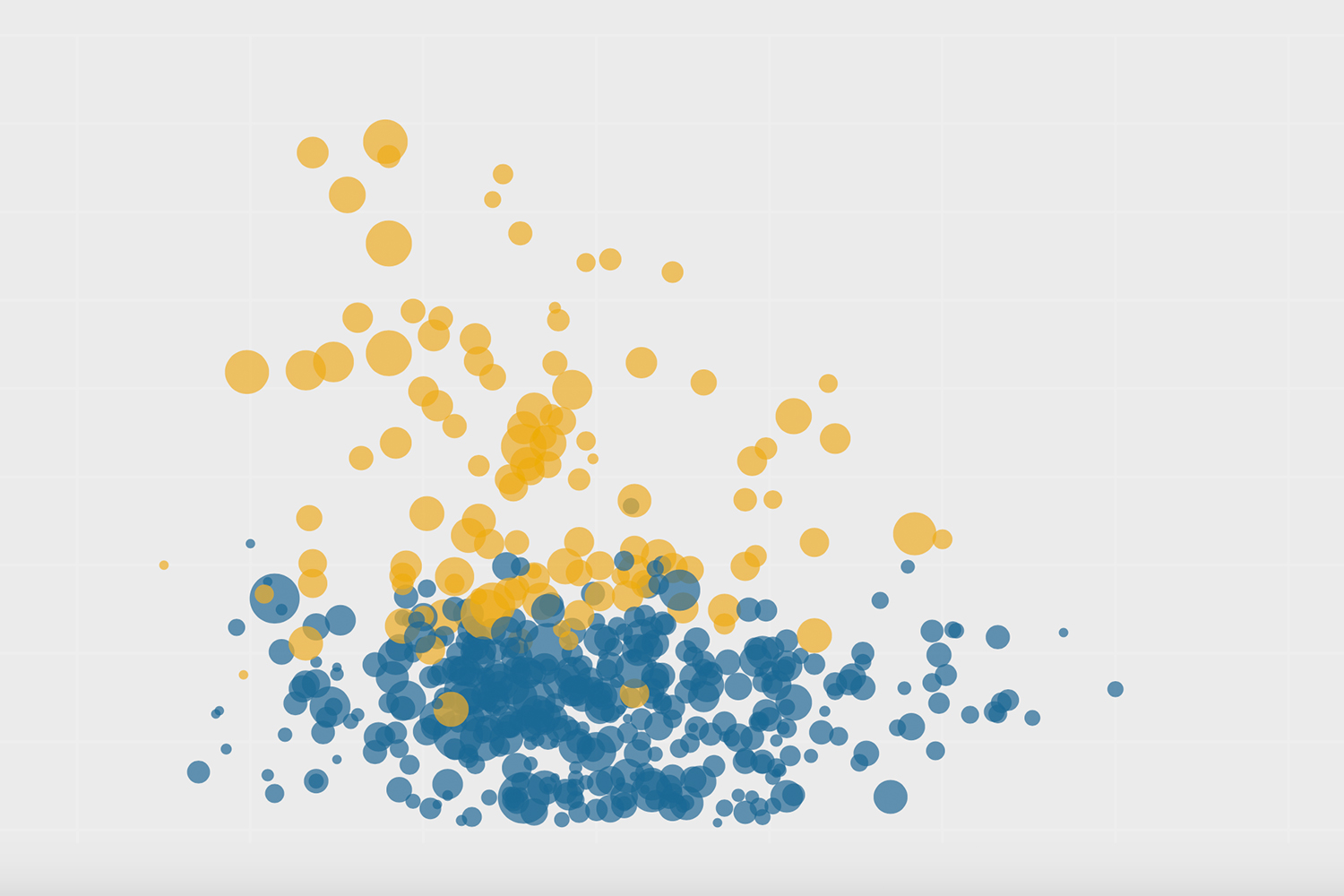

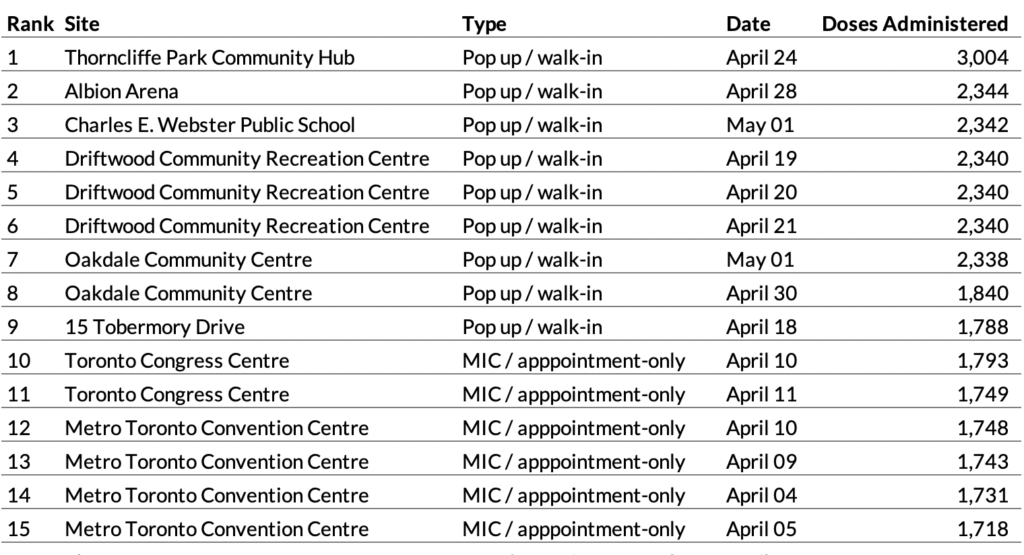

The Local has analyzed data from Toronto Public Health’s website which show dramatic declines in volumes at the nine MICs over the past month. In late March and early April, when they were the biggest game in town, the MICs in operation were administering roughly 1,700 doses a day. The Toronto Congress Centre peaked at 1,791 on April 10. The Convention Centre peaked at 1,748 doses, also on April 10. The volumes have since deteriorated, with the Convention Centre averaging just 707 doses a day last week. The Toronto Congress Centre? Just 437 doses a day.

All nine city-run clinics averaged just 638 doses a day last week, a stark drop-off when compared to the numbers at pop-up clinics, which regularly do 2,000 to 3,000 doses a day in much less robust settings—a tent in a park, school gymnasium, or ice rink.

[Disclosure: I’m one of the organizers of UHN OpenLab’s Friendly Neighbour Hotline, a group of volunteers that’s been called upon to support several pop-up clinics in the city.]

Daily Doses Administered at City-Run Mass Immunization Clinics, March 17 to April 30.

Data source: Toronto Public Health

Councillor Joe Cressy, Chair of the Toronto Board of Health, says the lack of transparency about volumes at the city-run MICs is not by design. “I think it’s a fact that throughout this pandemic, our approach at the city has been to collect all the data and share all the data as openly and transparently as possible.”

“If there’s a desire to also share the clinic-by-clinic breakdown at the MICs, we’d be delighted to,” he added.

According to Fire Chief Matthew Pegg, head of Toronto’s Immunization Task Force, the declining numbers are not due to any operational problems, but simply a matter of supply. “Our clinics are capable of administering significantly more vaccines each day than we are today,” said Pegg. “And that’s simply because we don’t have the vaccine to administer.”

However, the doctors and nurses who are actually delivering the vaccine point to problems with these clinics that have led to slowing numbers during a vital period in the vaccine rollout. This month, as supply grows and the province hopes to vaccinate 60 percent of those over 18, it’s become clear that MICs—enormous operations with robust budgets that were supposed to be the engines of the vaccination drive—are no longer leading the way. Instead, pop-up clinics in ice rinks and parking lots—led by community members, staffed by volunteers, and set up in a matter of days—are getting needles into arms at rates that far surpass what’s happening at the city’s mass clinics.

Friday, April 16 was supposed to be a vacation day for Sudha Kutty. The fiery, curly-haired executive from Humber River Hospital had been working non-stop, orchestrating vaccine clinics in Toronto’s northwest. That entire day, all she could think about was the escalating problems at her hospital’s flagship clinic: Downsview Arena. Volumes at the site—located within a short distance from several hot-spot postal codes—had been in decline, dropping below 1,000 doses a day for the first time since its initial week of operation. Vaccine supply wasn’t the issue.

No-shows had become a real problem at the arena. By-appointment clinics are prone to this because they’re always booking time slots in the future, so the moment someone with an appointment finds an available dose sooner, they’ll take it (per public health instructions). And because cancelling a booked appointment can be cumbersome, most people don’t bother. With each passing week, as people had more and more options to get vaccinated across different booking systems that don’t communicate with one another, the problem grew.

“In the beginning, it was small, maybe 10 [a day], and then it started to get up into like 100, 150, you know, and it became more problematic,” said Kutty.

But Downsview Arena had another, bigger problem: too many people showing up who didn’t fit provincial criteria. “The volume decline was because we were following the criteria and trying to make sense of it,” she said, referring to the 35-page provincial guidelines for operating these sites. Kutty said the guidance material had gotten more and more complicated over time, as additional eligibility criteria got tacked on: high-risk health conditions, age bands, workforce categories, and so on. It was beyond what Humber River’s rudimentary booking system could handle, and what registrants could absorb.

“Oftentimes our booking link went viral and was promoted on social media and all kinds of places. And they click and book an appointment and they show up for their appointment, and they were not in the booking category,” she said. Clinic staff spent much of their time at the door sorting out who belonged in which risk category and were forced to turn away people who did not meet the provincial criteria. People were angry, and it destroyed team morale.

“We had this one weekend where we ended up turning away at least 300, 400 people because they didn’t fall into the criteria,” she said. “Colossal waste of time, not helpful to the community.”

Between the no-shows and the people screened out at the door, throughput at Downsview Arena had dropped from a high of 1,416 a day at the beginning of April to just 929 on Kutty’s day off. That’s hundreds of doses below the facility’s true capacity—hundreds of doses not in the arms of residents in one of the highest-risk areas of the city.

Kutty has spent much of her career doing health care quality improvement—the science of constantly tinkering with processes to squeeze out even the smallest ounce of performance from a system. It’s the kind of perpetual problem-solving mentality that never quite stops, even on days off. That Friday afternoon, the light bulb went off for Kutty. And by evening time, she was back at the hospital to meet with her boss, Barb Collins, Humber River’s CEO.

“Barb, I’ve been thinking about this all day,” Kutty said to her boss. “I think we need to change our strategy. We have like a 25 percent positivity rate in some of these hot spots and we have to vaccinate this community.”

Collins couldn’t agree more. “I remember when I was there on the one Saturday and an old man came over, he had walked over from the condos across the street, and he said, ‘I don’t know how to book in, can I just please come and have a vaccine?’” recalled Collins. “And that’s when we said, ‘You know what? What we’re doing is ridiculous.’”

“When you talk about vaccine hesitancy, sometimes you only get one chance with that person,” said Kutty. “They come to the door and you say no, what are the chances of them coming back?”

That weekend, they drew up a new game plan: abandon their directions from the city and province, and throw away the booking system all together. People looking for a vaccine would no longer need to have an OHIP card or the internet, and the clinic would be open to anyone 18 years of age or older living in the surrounding postal codes. Downsview Arena would operate much like a pop-up clinic, but with a hard roof. Anticipating potential push-back from government officials, Kutty and Collins worked up an argument in case they were questioned: it’s no different than if they were to shut down the arena and moved everything into a tent in the parking lot. They felt like they had a solid case, and went ahead with the transformation.

A couple of days later, on April 20, the new plan went live. “The Tuesday was great,” recalled Kutty. “We had all these flyers printed out and I walked around to the No Frills, to the LCBO, to the Dollarama, to the Food Basics, to the Bank of Montreal, to the bakery, and handed out flyers to people. I got on the bus and handed out flyers on the bus.” She also arranged for the bus driver to come get a shot after his shift.

They administered 1,488 doses that day, and volumes have hovered around 1,500 a day ever since.

Dr. Silvy Mathew is a family physician who has worked at pop ups and MICs. In her response to my tweet comparing throughputs at pop ups versus MICs, she said: “There is zero comparison, at a pop up I can do 12-15 patients per hour with exact same care/education provided. At [The Metro Toronto Convention Centre], I do at best half that rate.” She said that MICs are hampered by booking system issues: people double booking at different sites resulting in no-shows, people showing up who don’t qualify, and that there’s too much time allocated per patient, as well as overstaffing compared to the actual volume seen.

According to Pegg, however, the city-run MICs do not have a no-show problem. “Ours is very low,” he said. “We’re seeing less than 1 percent [no-shows] in the last data that I had.”

Pegg indicated that when the Convention Centre is operating at maximum capacity, meaning with 40 vaccinators over a nine-hour clinic day, the site could administer 2,160 doses. Doing some quick math, you realize that these numbers are based on a vaccinator administering 6 doses per hour—precisely half the rate Mathew says she does at a pop up.

Pegg acknowledged that walk-in pop ups and by-appointment MICs are two very different vaccination models, meant to serve different types of people, and have their distinct advantages. Both are important parts of an effective vaccination campaign in the big scheme.

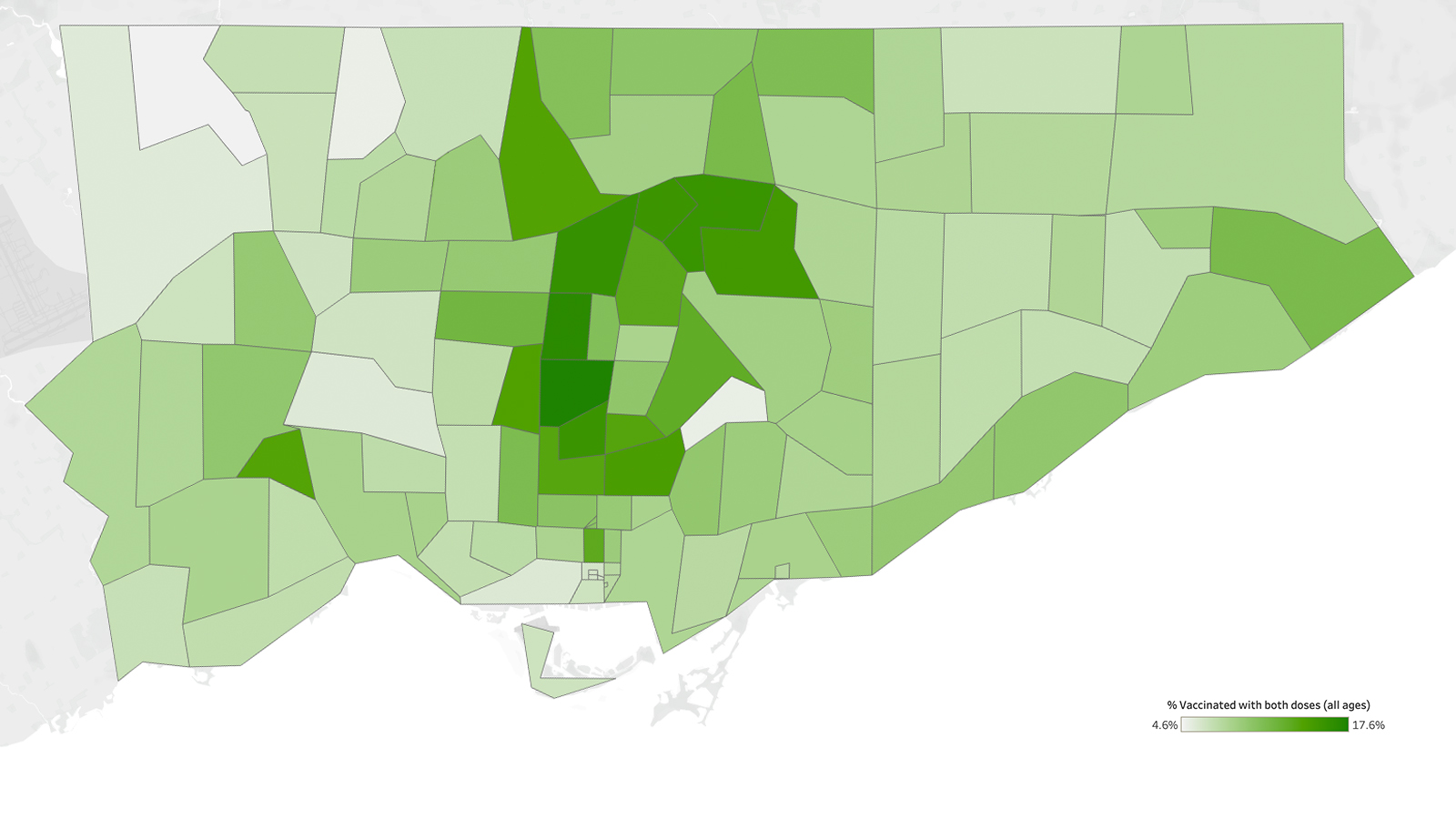

Pop ups have become popular among residents of Toronto’s hardest-hit neighbourhoods, almost too popular at times—drawing huge crowds and painfully long lines. No one knows this better than Phil Anthony of Michael Garron Hospital. He’s the architect behind some of the highest-volume clinics in the city thus far, including the pop up in Thorncliffe Park two weekends ago that did 3,004 doses on a single Saturday, a record for Toronto. In fact, four out of the top six clinics in Toronto were Anthony’s, including the three at the Driftwood Community Recreation Centre in the Jane and Finch area.

The mild-mannered ED nurse turned pop-up pro isn’t so quick to take credit. “To be able to get high volumes like that in a one-day setting, you need to have proper outreach,” said Anthony. “We rely heavily on our community partners to flyer the apartment buildings and, you know, contact local groups or agencies to make sure that they’re aware of the pop up as well.”

Site selection is also crucial. Anthony prefers locations surrounded by high-rise buildings in order to draw on their dense populations. It’s also important for the clinic to be located in a trusted space for the community, and one that is accessible, preferably by foot.

“What’s different about the pop up is it really creates a convenience factor,” said Anthony. “The people who may not be able to spend money on bus fare to get to a clinic or people who may not be able to take a day off work, you’re going to make it as convenient as you can for them.”

But lately, that convenience has come at a price. Mainstream and social media footage of long lines that go on for blocks have shaped the image of pop ups as both a success and a failure, depending on how you look at it. On the one hand, the lines have raised awareness about the need for vaccines in these communities, and helped to counter the narrative that vaccine hesitancy is rampant. On the other hand, they’ve wreaked havoc with clinic operations. Unlike the MICs, the big drawback of pop ups is the lack of predictability. There is rarely a steady stream of people; flow seems to be constantly oscillating between an open fire hose and a drippy faucet.

The teams operating these pop ups have found ways to smooth out clinic flow, especially during the early morning hours when lineups are longest. “One the most important things you can do is bring your registration staff in early, so they can register almost the whole line before you start the clinic,” said Anthony alluding to the fact that checking ID, and entering patient data into the provincial system is the rate-limiting step in the whole operation. “My clerks start about an hour and a half early, and they register probably 600, 700 people before the clinic even starts.”

There is rarely a steady stream of people; flow seems to be constantly oscillating between an open fire hose and a drippy faucet.

Anthony believes that the over-coverage of lineups by the press has damaged the reputation of pop ups. “I think people are concerned that they are going to show up and not get the vaccine, whereas, all these pop ups work so efficiently that, now, the line really disappears after two hours and then it becomes very convenient.”

Anthony’s successes have earned him a seat at the newly-formed Toronto Mobile Vaccine Strategy Table, where he is the co-chair. The Table’s mandate is to expedite vaccination efforts in the city’s COVID hot spots through targeted mobile and pop-up clinics.

In the next months, as vaccine doses begin arriving fast and furious, Anthony’s only focus is on throughput: how to get doses into the most arms efficiently. His goal is to eventually do 6,000 doses a day, an obscene number by current standards. To do it, he’s thinking about adopting one of the strategies of the mass immunization clinics: after the initial morning rush at a pop up, why not fill the afternoon lull with pre-booked appointments?

That flexibility and focus is what’s needed in the next, vaccine-rich phase of the rollout. Sticking too rigidly to existing paradigms—whether at pop ups or MICs—without adjusting to the new realities of vaccine supply will mean missed opportunities. It will mean doses that should have been in someone’s arm today, sitting in freezers until tomorrow. And ultimately it will mean delaying our ability to achieve mass immunity and to finally put an end to this long pandemic.

Correction—May 9 2021: The original article stated that the average number of doses administered at city-run clinics last week was 663 per day. This has been corrected to 638.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.