Here we are, on the cusp of another winter break, with another school year about to be usurped by an unrelenting virus taking advantage of the tired and weary.

A year ago this week, students came home with a foreboding pile of school materials meant for lessons after the holidays. Just days later, the government announced that starting Boxing Day, Ontario was entering the Grey Zone (remember that?). In Toronto, that was supposed to mean one extra week at home for elementary school kids and three for secondary school students. In reality, after multiple extensions, it wasn’t until mid-February that exhausted parents, students, and teachers were relieved of their virtual learning duties. From there, the return to in-person schooling lasted just seven weeks, before being shut down for good after the Easter long weekend in an effort to limit the third wave.

This year, Toronto’s massive public school system, the largest in the country, is limping into the winter break severely wounded, with school cases, disruptions, and outbreaks at their highest levels. The break arrives at a time of rapidly rising infections in the city, a surging Omicron variant that’s more transmissible, and a kids vaccine rollout that’s still in its infancy.

Not surprisingly, but to the distress of anyone connected to the public school system, the TDSB sent out an email on December 15 asking parents to prepare for the worst: “Out of an abundance of caution and to ensure your family is prepared for any shift to remote learning, be sure your child brings home all of their personal belongings such as shoes or clothing, and any tools or supplies they might need to pivot to remote learning.”

If there’s a glimmer of hope in the weeks ahead, it’s the fact that unlike last year, there’s an approved pediatric vaccine. But it takes time to roll out the vaccine’s two-dose regimen, time that we’ll need to buy by sacrificing the very thing that we need right now—a holiday. It’s a bitter pill, I know, but our options are limited at this point and the window is narrowing quickly. To keep schools open after the holidays and avoid a repeat of last year’s nightmarish scenario, federal, provincial, and municipal forces will need to converge and, individually, we’ll need to settle for something lesser than the holiday festivities we envisioned just a couple of weeks ago. Ideally, the following things would happen:

The two-dose kids vaccine would be administered three weeks apart, like in the United States and in the clinical trial. Clinical-trial data showed that the Pfizer vaccine was 90.7 percent effective for those five to 11 years old when given three weeks apart. While the federal decision to go with the longer interval of eight weeks—which is known to enhance immunity—was understandable when it was made, the incremental gain of a few percentage points is probably not worth it with Omicron staring us in the face. To put it another way, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) and Health Canada came to their conclusion before there was knowledge of Omicron, and it’s unlikely that they would have arrived at the same conclusion knowing what they know now. Technically speaking, kids can receive their second dose after less than eight weeks if required and with informed consent, but that’s in the fine print, and it’s the exception rather than the norm. It needs to be made the norm if we want as many school children to be fully vaccinated in early 2022 as possible, and to potentially avail themselves of a booster shot before the end of the school year, should that come into play.

Stricter social gathering restrictions would be reintroduced to slow down Omicron and buy time. This is by far the least palatable among my suggestions. The idea of shutting things down is devastating. But if Ontario wants to uphold its promise to make schools the last to close and the first to open, it’s a step that we need to be prepared to take. I’m not sure exactly how strict those restrictions should be, but it’s going to take more than capping capacity at 50 percent for sports and entertainment venues with 1,000 or more people, as Premier Ford announced on December 15.

While the government’s preferred antidote to Omicron appears to be vaccines over restrictions, the reality is that vaccines take time to administer and kick in. With Omicron doubling every three days, according to Ontario’s Science Advisory Table, vaccines and restrictions need to work in tandem. Without further restrictions, Omicron’s exponential growth over the next few weeks will begin to overwhelm schools and hospitals in January. At that point, only the most drastic of measures will do.

A vaccine blitz over the holidays that zeros in on high-risk neighbourhoods. The Ford government’s aggressive and urgent position on vaccines is good: booster shots for anyone 18 and over starting December 17, a shortened interval of three months instead of six, and scaling up capacity to the previous peak of 200,000 to 300,000 doses per day across the province. In Toronto, this was quickly met with the city’s own announcement that it would double capacity at its five mass immunization clinics (MICs).

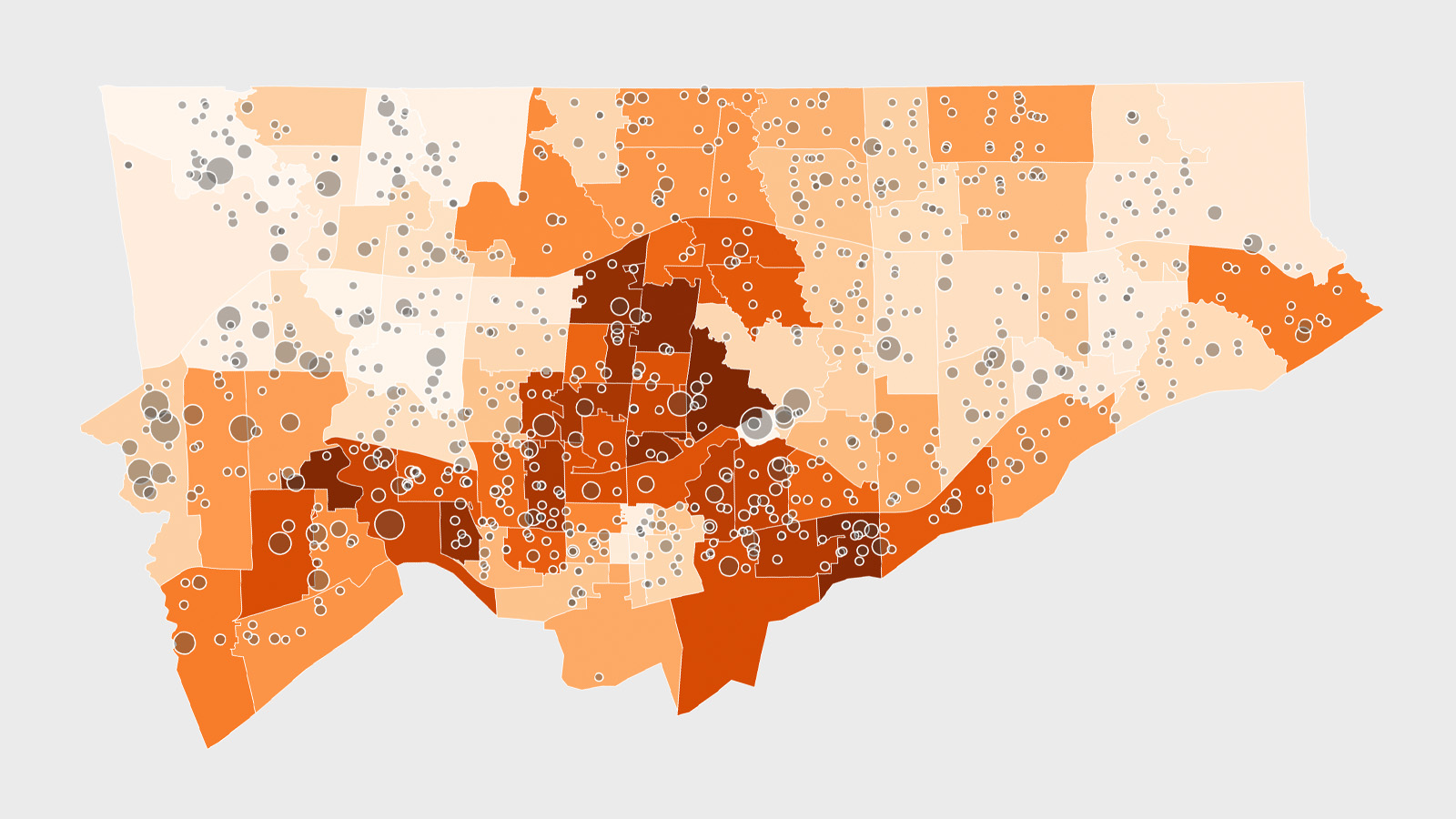

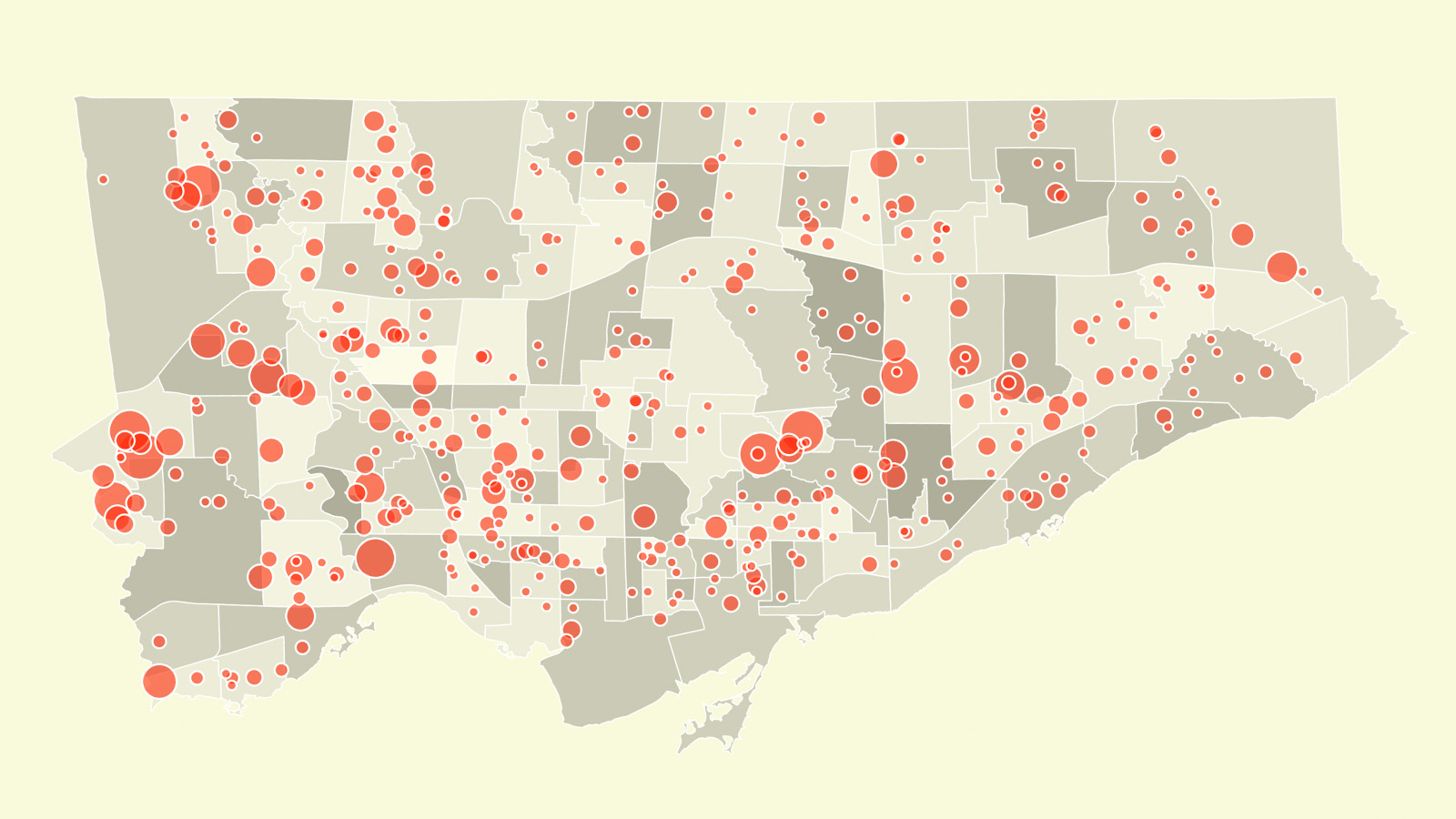

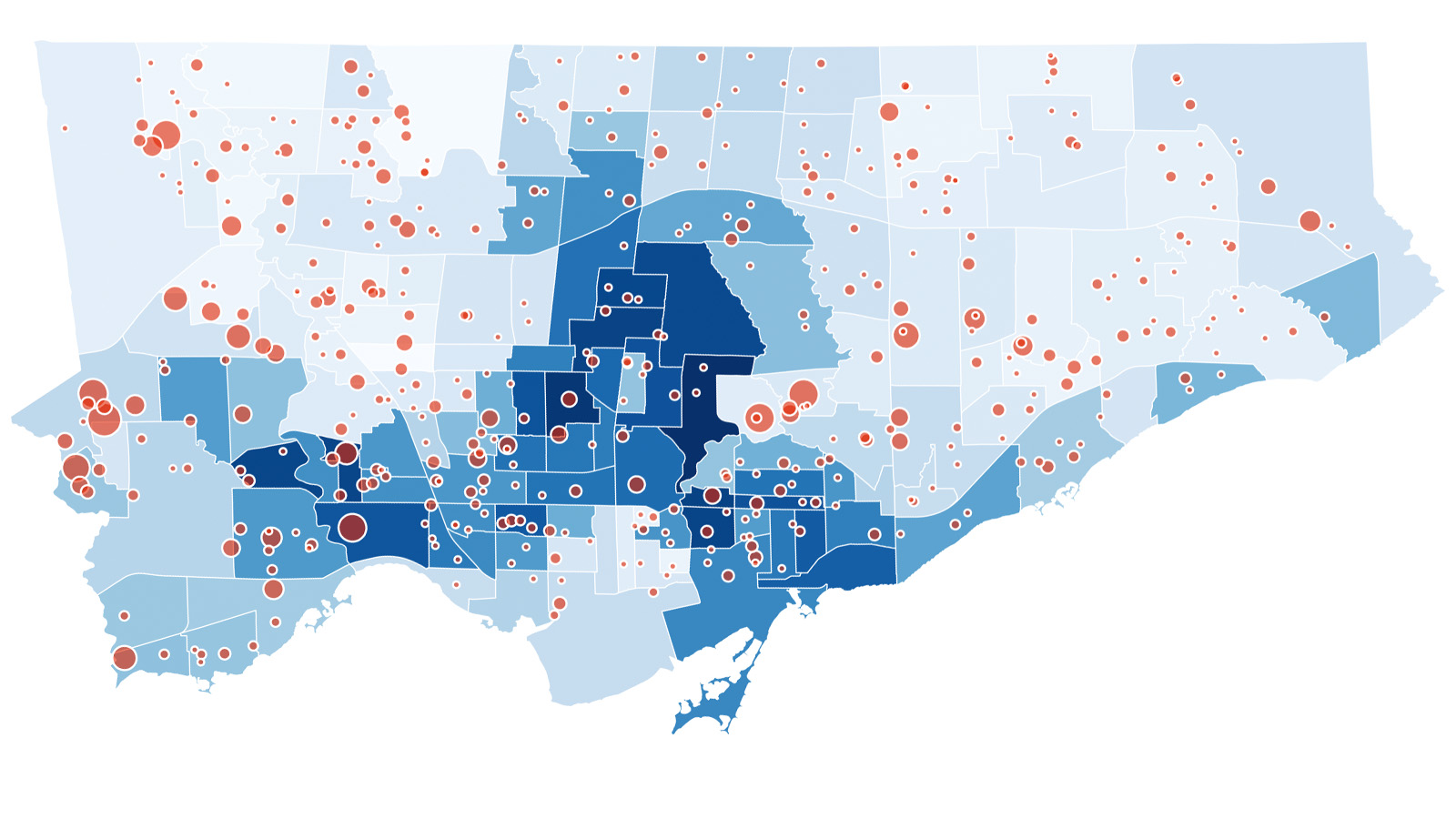

However, as we’ve seen throughout the vaccine rollout this year, it’s not just the number of doses that matters, but also who gets them. We know that neighbourhoods that are home to schools with the largest COVID outbreaks and most numerous infections are among the least vaccinated. The doubling of capacity at the MICs will need to be twinned with a doubling, if not tripling, of capacity at community-based clinics in the high-risk areas of the city just to keep the disparities from widening. During the winter break, schools will be vacant, and there is no reason why we can’t have pop-up clinics in the numerous empty gymnasiums across the city, particularly in areas where vaccine coverage has lagged. Such clinics would double as places to get both the pediatric vaccine and booster shots, attracting kids, parents, and grandparents alike.

Rapid antigen testing would be widely available and used to minimize outbreaks when schools resume. During the winter break, each student has been given a standard-issue rapid antigen test kit and encouraged to test every three to four days until they return to in-person learning in January. What happens after that is unclear. According to the Science Table, rapid antigen tests can be an important tool to reduce transmissions in schools when used to screen for asymptomatic cases. Once a Public Health Unit or neighbourhood approaches 50 new daily cases per million (Toronto is already above that level), it recommends voluntary testing of unvaccinated and incompletely vaccinated elementary school students once a week. As new daily cases approach 250 per million, testing frequency should increase to two to three times per week. Even with a dramatic uptick in pediatric vaccination over the holidays and a shortened interval of three weeks between doses, a large number of students will remain incompletely vaccinated by January, especially in the neighbourhoods where vaccinations have barely begun. Like restrictions on social gatherings, rapid antigen tests will buy time for elementary school students to get fully vaccinated.

None of the solutions suggested above are new. They are all things we’ve done before, at one time or another, in one form or another. They now need to be done in concert and in pursuit of one of the few common interests we seem to have left: keeping schools open. Yes, after nearly two years of this, our tank is getting empty and things don’t seem to be getting better. But if keeping schools open after the holidays, and avoiding a repeat of last year’s dreadful scenario is what we all say we want, then we need to get a move on—fast.