Terence Leung, a solo family doctor in Toronto, knew that a lot of his patients were missing out on vaccines. Some were old and couldn’t get around easily. Others weren’t online. Some just didn’t feel comfortable in English. So on the last Friday in May, he decided to hold a small vaccine clinic in his storefront office at Gerrard and Greenwood.

It was a cold, drizzly day, and the patients, all pre-booked, lined up on the sidewalk out front. An “usher” greeted them at the door, and inside, his receptionist checked them in with their health cards. In his small waiting room, Leung had chairs for two patients, separated by a makeshift curtain; another patient sat in an examination room down the hall, and up to three family members could sit together in a room at the back that had its door cracked open.

Leung, who’d given a lot of thought to the logistics, mostly vaccinated patients where they sat, then logged their dose through his computer. “I’m the one that’s moving,” he told me. His office manager, his wife, also moved: monitoring the patients afterwards and doing their check-out.

“The patients appreciate it,” says Leung. It was quick and familiar for them. Altogether, Leung vaccinated 44 patients that morning, with zero no-shows.

Leung had already vaccinated over a hundred of his elderly patients back in March and April, during four clinics he did alongside the Bridgepoint Family Health clinic down the road at Broadview. Both Leung and Bridgepoint are part of the East Toronto Family Practice Network and they were sharing space and expertise. Leung and five other solo doctors and staff not only got tips about set up and patient flow, they also got training on the province’s electronic vaccination management system, known as COVaxON.

Leung doesn’t think running his own vaccine clinic was anything special, and in ordinary times, it wouldn’t be: family doctors dominate vaccination, giving shots from infancy through old age, and running flu clinics every autumn.

COVID vaccines, however, have been a different story. Family practices have played almost no part in the rollout. But with hospitals poised to ramp back up, and with a backlog of surgeries and procedures and specialist appointments and diagnostic testing, it’s gradually dawning on everyone that the folks who’ve been managing the vaccine campaign thus far are no longer going to have the bandwidth to continue. Someone’s going to have to take over.

“The leaders of the health system who have so effectively managed the acute care crisis are going to have to hand the baton to their primary care colleagues,” says Danielle Martin, chief medical executive of Women’s College Hospital, and a family physician. They are the ones, she points out, who know how to manage infectious disease in the community over the long haul.

But the plan for that transition remains elusive. “Is there a plan?” asks Liz Muggah, president of the Ontario College of Family Physicians. “We have not seen that plan.”

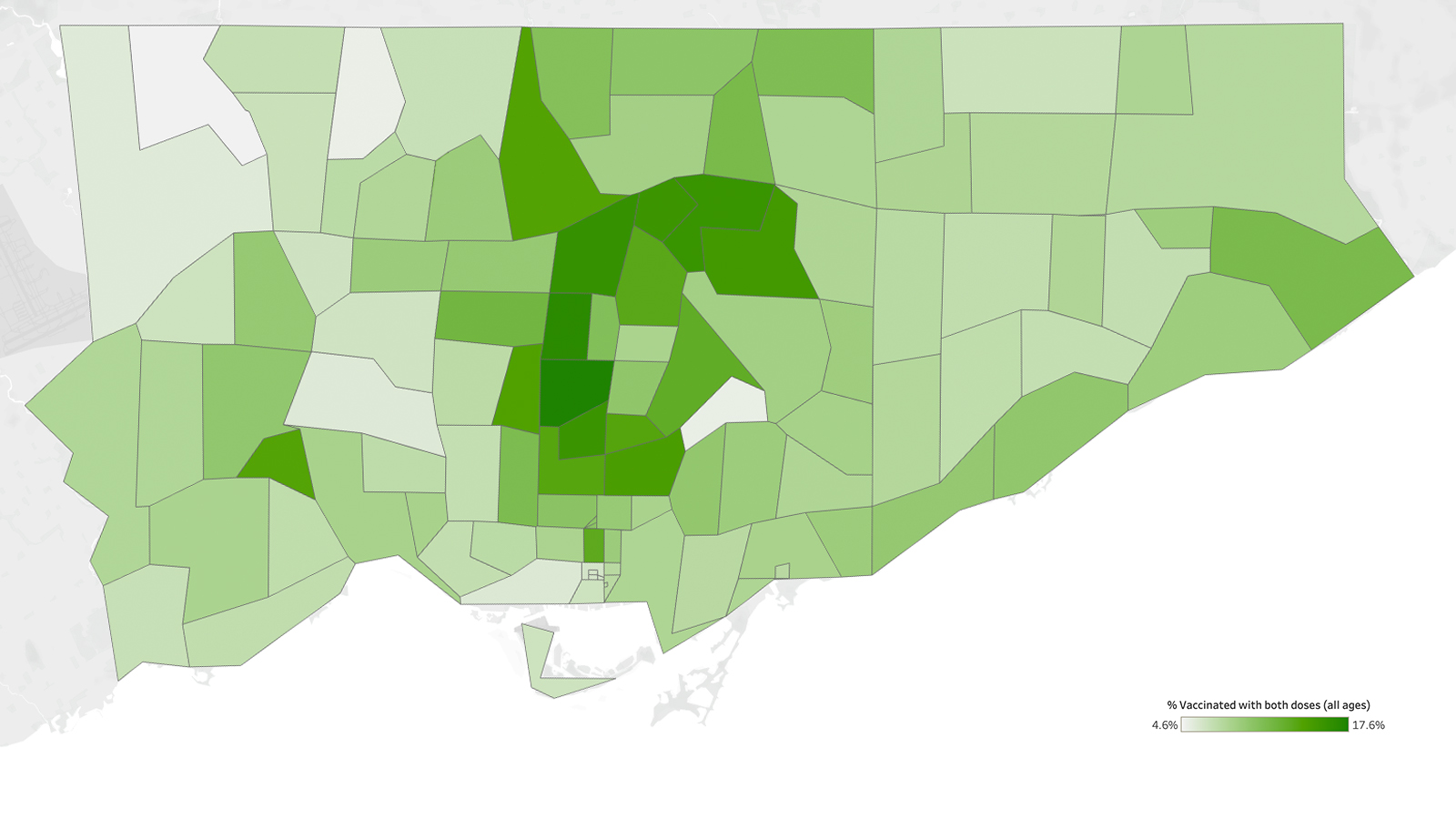

Vaccines come into the province via the federal government, but drawing a flowchart of what happens next isn’t easy. Much of the allocation happens within each of the 34 public health units. Toronto Public Health, for instance, runs its own mass vaccination clinics, but also channels vaccines through “hospital hubs.” According to Toronto Public Health, 2,202,980 doses have been administered in Toronto so far.

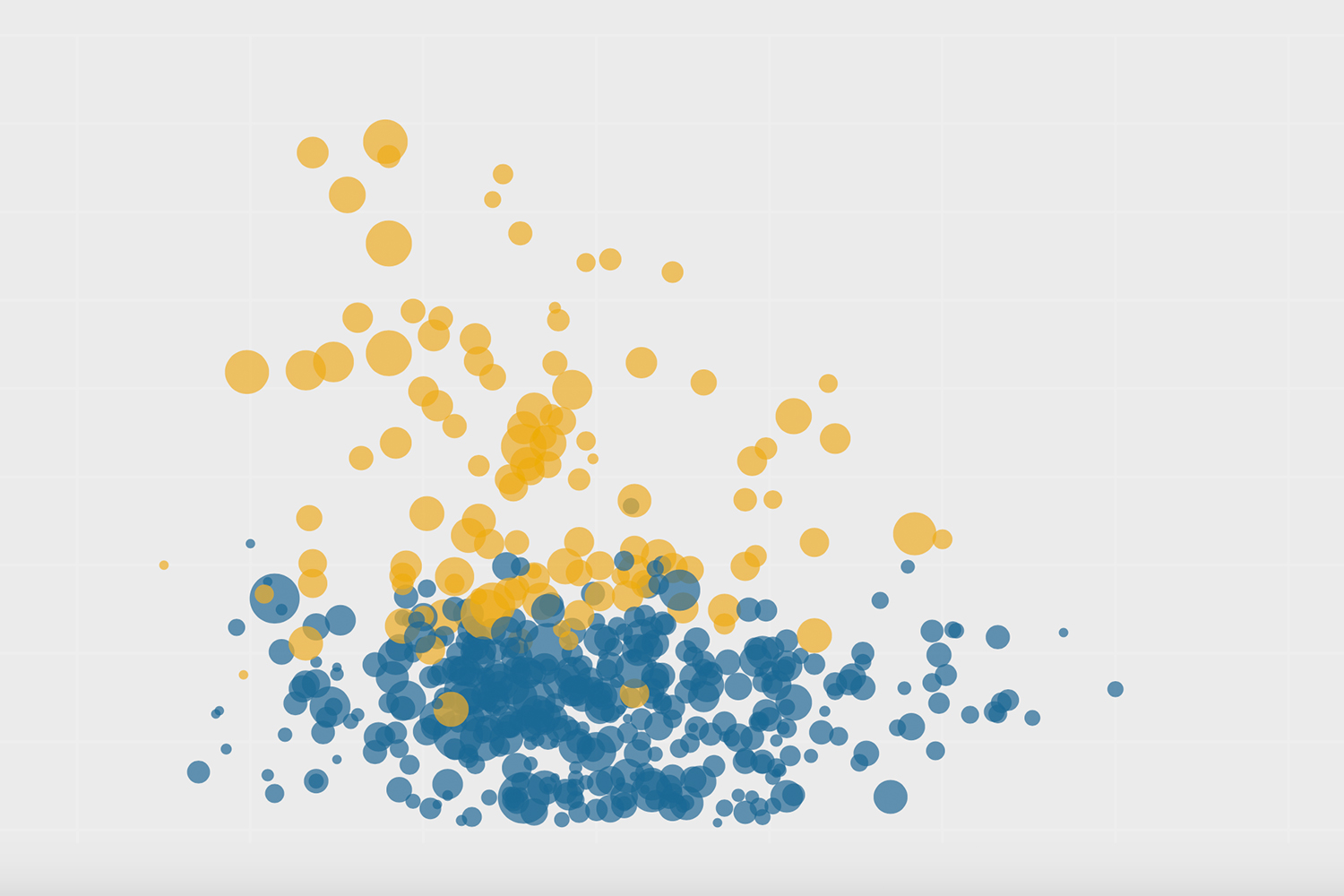

Vaccinating en masse, at workplaces, and in hotspots has been efficient, but those strategies miss certain kinds of people. Needles were going into the arms of 12-to-17-year-old keeners, even as a lot of seniors remained unprotected. As of June 2, 27 percent of Torontonians over age 80 were still unvaccinated, according to Toronto’s medical officer of health, Eileen de Villa. “Seniors are not going to stand in line for three hours at a pop-up with a DJ,” says Martin. They also might need reassurance from a doctor they know personally. Martin thinks that the shutout of family doctors is a key reason vaccination in the older age bracket stalled.

While there were supply glitches and cold storage challenges at the start, pilot projects showed that family doctors could manage even Moderna and Pfizer in their offices just fine. Polling suggested that almost half of Ontarians wanted to get their shots from their family doctors; family doctors, by and large, wanted to give them. What little vaccine supply got to doctors like Leung or the team at Bridgepoint, however, often flowed through hospital hubs like Michael Garron.

Many people are baffled as to why delivery through primary care isn’t seen as at least one prong in a many-pronged approach. “I find it puzzling,” says Muggah. “It’s very clear that you need to use all options.”

It’s not that family doctors haven’t been active in the rollout. They have been staffing the mass vaccination clinics and the pop-ups, driving doses to homebound patients, and vaccinating in shelters. They’ve also been answering their patients’ questions as best they can, and helping people sign up to get their doses. “The day that those shipments came in, I printed my list of every patient in my roster by date of birth. And I personally phoned everyone 80 and older,” says Martin. “We all did it.”

But whereas some of the province’s public health units worked with family doctors to get those patients signed up quickly through the backend, in Toronto, family doctors were left to use the same congested online portals and phone lines as anyone else, says Tara Kiran, a family doctor at St Michael’s Hospital. There was not the level of collaboration you would expect, she says.

Allan Grill, chief of family medicine at Markham Stouffville Hospital, says things were different in York Region. There, a task force was created that brought together the heads of all the various primary care teams. “We meet twice a week, and we all have input into what’s happening,” says Grill. He feels their ideas are being heard. “That was not the same in every public health unit.”

Grill thinks public health got it largely right. “If you look at some of the public health unit plans, most of them, including York Region, had primary care as part of their plan. But they had them a little bit further down the road,” he says. “And—this is my opinion—I don’t think primary care offices were the answer to getting the numbers we needed to get vaccinated from day one.” There are genuine barriers for many family practices to do this, he says.

Even Karen Chu, medical director of the Bridgepoint Family Health Team that buddied with Leung, admits that running vaccine clinics is not for everyone. Toronto family practices may not have the physical space needed for distancing and for the 15-minute post-vaccine observation, she says. They may not have the administrative capacity, or the time to take away from their regular appointments. “It’s a lot of manpower to run them,” she says.

But future doses may increasingly fall onto the shoulders of family doctors and pharmacies, and we need to be prepared. Grill thinks that will work well. Booking will be easy, he says: “All of our patients know how to book appointments.” Or they can do walk-ins through pharmacies.

But just figuring out who remains unvaccinated or needs a next dose is going to be arduous. The COVaxON system is not integrated with doctors’ electronic medical records. “I don’t even receive notification when my own patients are immunized,” says Martin. There’s a field to input the name of the family physician, she says, but it’s optional. “And in all the vaccine clinics I’ve worked at, I’ve never seen it filled out.”

Kiran wonders why it didn’t come pre-filled. “The government has all this—who’s rostered to which family doctor. Why not put it there from the start?” Instead, doctors have to manually input each patient’s vaccine status.

If family doctors had been involved in designing the rollout, of course, they would have thought about this. But they weren’t involved. The province’s COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Task Force, assembled to devise the best way to get the vaccines out, includes a coroner, a former police chief, the CEO of an air ambulance service, and a couple of deputy ministers among its 10 members, but not a single primary care practitioner.

“Why we weren’t included in that initial table from the get-go is a bit bewildering,” says Erin Bearss, a staff physician at the Mount Sinai Academic Family Health Team. “Why wouldn’t they ask the people who actually do this on a day-to-day basis?”

With the transition looming, we may soon all be asking that question.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.