In the summer of 2021, with Toronto in the grip of both the pandemic and an increasingly catastrophic housing crisis, city officials began telling the hundreds of people that had found a semblance of refuge in its public parks to get out immediately. They did it in Lamport Stadium, in Alexandra Park, in Trinity-Bellwoods. To make their message abundantly clear, they sent in hundreds of riot police, horses, and security guards, most of whom did not take kindly to the rapidly assembled community members who showed up to protect the people they often referred to as their “neighbours in tents.” Cops assaulted, kettled, and pepper-sprayed protestors, tore up tents, trashed personal belongings. Unhoused residents scattered—some to shelters and shelter hotels, others to the couches and floors of friends’ apartments, still others to less visible encampments in ravines and under the Gardiner.

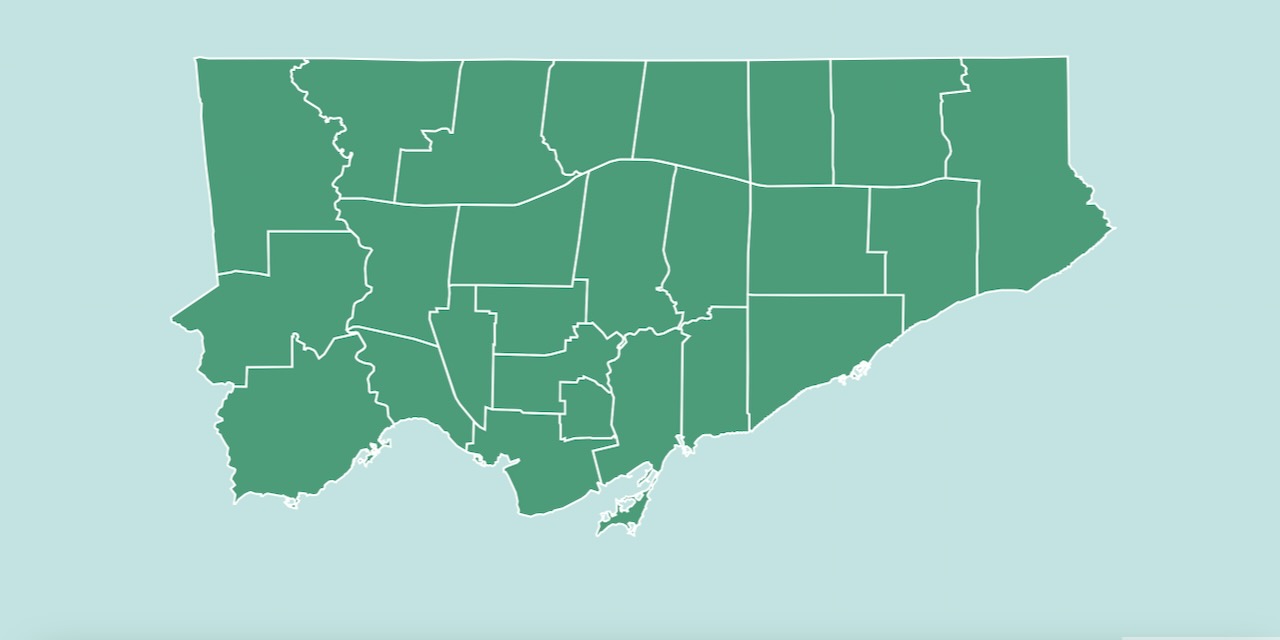

A fair number of people, however, made their way a bit further north to Dufferin Grove Park. Across the street from the Dufferin Mall, Dufferin Grove was beloved for its sun-dappled playground, farmers’ market, and weekly community meals. It was also located in Davenport, Ward 9, whose councillor at the time was Ana Bailão. By that point, Bailão had been on council for eleven years, where she had spent much of her time specifically on affordable housing. She got laneway housing and garden suites approved, developed CreateTO, an agency to build affordable housing on city-owned lands, and spearheaded the city’s ambitious ten-year housing action plan, which launched in 2020. She became Mayor John Tory’s so-called housing czar, and in her last term, was Deputy Mayor for housing and Chair of the Planning and Housing Committee.

But some progressives and activists felt Bailão hadn’t done enough, or that she hadn’t pushed her boss to do enough. To them, the encampments themselves were proof of that failure, and the City’s violent response a blunt admission of dysfunction and paralysis. All over North America, housing had become an impossibly complicated puzzle, but Toronto, with its outdated zoning laws, overheated real estate market, and low property taxes, was a more confounding puzzle than most. In the summer of 2021, the average Toronto home sold for $1,089,536, and it cost, on average, $17,172 a year to rent a one-bedroom apartment, prices far beyond the average household. There were almost 80,000 households on the waiting list for social housing. That year, 216 unhoused people died in the city, 72 more than the previous year.

New Candidate Profiles Each Week

Sign up to get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

The evictions had been controversial and expensive, and they had done nothing to solve the affordable housing shortage that made the encampments inevitable. But when tents started to pop up in Dufferin Grove, just a few blocks from where Bailão herself lives, she went to the mayor’s office and said she wanted to try a different, “housing first” approach. She put together a working committee that included members of non-profits like Dixon Hall and Alliance to End Homelessness, and they began meeting weekly to see how they could move residents into permanent housing. They set up I.D., tax and ODSP/OW clinics to help expedite residents’ applications for such housing. Bailão herself visited the park once a week, sometimes after a run on a Sunday morning, where she spoke with both unhoused residents and their supporters. “I was just really trying to listen to them, to see where they were coming from, and connecting with them,” she told me. This support model became known as the Dufferin Grove Pilot Project, and it ran from early August to late December. At its conclusion, 25 people were moved into permanent housing, with another 88 into shelter hotels. In the Ombudsman’s otherwise damning report on the encampment clearings, which was released this past March, he called Dufferin Grove “a progressive leadership model” and recommended that officials use it with all current and future encampments. “The City recognizes it as a success,” Bailão said.

Others, however, saw it in more equivocal terms. Aliya Pabani, an organizer with Encampment Support Network Parkdale, argued that the City should have offered these same health and social supports in the first place, at Trinity-Bellwoods and elsewhere. And while she and ESN-Parkdale were pleased that the City had secured permanent housing for several residents, they were frustrated and angry that many more were moved into shelter hotels on the promise of housing that has yet to materialize. Many of those shelter hotels closed or are closing, and residents are again being funnelled into the same overcrowded, unsafe congregate shelter system they originally fled. “Beyond the grief of ‘going backwards,’ the experience has been retraumatizing,” Pabani told me.

Pabani was also skeptical of Bailão’s role at Dufferin Grove. She said that ESN-Parkdale members only saw her in the park a couple times and that they didn’t see her talking to any unhoused residents. More significantly, Pabani insisted that it was only under pressure from her group and other activists that the City shifted gears at all. “It takes unhoused people collectively resisting their forced displacement, alongside broad public support, to provoke a meaningful government response,” Pabani said.

Bailão retired from council in 2022, and took a job as head of affordable housing and public affairs with Dream, a major Toronto developer. Just three months later, however, after Tory resigned after revealing he’d had an affair, she joined dozens of others in the race to replace him. And, with housing arguably the most important issue in this election, Bailão’s record has become both a potential liability and her greatest weapon. Some, like Pabani, argue that Balãio’s consistent alignment with Tory only reinforced a dismal status quo: “Looking at the past 5 years, Ana is likely to vote ‘yes’ on whatever housing issue comes across her desk, as long as it’s sufficiently vague, or focused on fact-finding. When policy gets specific, Tory and his cohort have consistently voted ‘no,’ as has Ana.” Others, however, believe she’s accomplished more on the file than pretty much anyone in municipal politics. “Ana understands very, very well, that housing is integral to everything,” Doris Power, a long-time housing and disability activist, told me. “Mental and physical health, employment, family togetherness, children, education—housing is integral to all of it.” Now, the issue was integral to Bailão’s political future too.

In Bailão’s telling, she’s been preoccupied with where, and how, people live from the moment she set foot in Canada. In 1992, when she was 15, her parents—Beatriz and José, a seamstress and mechanic respectively—emigrated from Portugal to Toronto, settling at Dundas and Brock. The move wasn’t easy—Bailão didn’t speak English, she was leaving behind friends and a beloved grandmother, and her parents had to work long hours to make ends meet. (In Toronto, José also moved into construction.) She attended West Toronto Collegiate and for a couple years, a typical day meant school, then taking her younger sister, Sara, home, and joining Beatriz to clean offices from 5:30 til 9:30, followed by homework.

The family rented at first, then bought their first house three years later. For the teenaged, earnest Bailão, who dreamed of one day becoming a social worker, that starter home meant both safety and opportunity. “It was the most powerful feeling I ever felt,” she told me. “That everything was going to be okay. That this was a city that worked.”

Bailão studied sociology at U of T, and, while at school, became involved in community organizing. Her work soon caught the attention of city councillor Mario Silva, who persuaded her to become his executive assistant while she completed her degree. That ended up being a five-year gig, with Bailão helping out on various fronts: working with residents’ associations, park improvements, transportation, day cares. She adored what she calls “the city stuff,” and, in 2003, when Silva ran federally for the Liberals, she stayed put, deciding to run as a councillor herself. She was 27, had been in the country for just over a decade, and at her first meet-the-candidates event, she trembled violently, embarrassed by her accent and deathly afraid that she would misspeak. She lost to TTC chair Adam Giambrone by 1,200 votes.

In 2010, after stints in banking and healthcare I.T. marketing, and also serving as president of the Working Women Community Centre, she ran again, and won. Her path to City Hall was different than that of her colleagues—she hadn’t been a school trustee, for instance, nor did she have much in the way of name recognition. She was also elected in the same term that Rob Ford became mayor—akin perhaps to getting your first ship crew job aboard the Titanic. But Bailão found common purpose with a small group of rookie councillors that included Josh Colle, Mary-Margaret McMahon, and Josh Matlow, and who were dubbed, depending on your perspective, “The Mushy Middle” or “The Mighty Middle.” Some considered them too deferential to Ford—killing off the Jarvis bike lane, for example—but they also pulled off budget coups, stifled Ford’s plan for a subway to Scarborough, and largely avoided the political polarization that often paralyzed council. “To keep your backbone and stand for certain things was really hard in that term,” said Councillor Shelley Carroll, “and I watched her do it.”

By all accounts, the thing that Bailão stood up for most often was affordable housing. It was a quixotic choice for a new councillor. For one thing, housing is a dizzyingly complex issue, involving all levels of government, thickets of regulation, fractious stakeholders, tricky math. The affordable housing committee, of which she was chair, wasn’t even a standing committee at the time, but more of a subcommittee that met just four times a year. The budget was $96 million. She was told that no one cared, on council or otherwise, and that to even mention the issue in campaign literature could cost you votes. But Bailão was convinced that the city’s lifeblood was in its housing and that its shape, affordability, and accessibility was entirely foundational. “It’s key for the social and economic health of the city,” Bailão said. “If we can’t have people, and especially workers, able to afford to live in the city, then what are you left with?”

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

Joy Connelly, an affordable housing advocate and consultant, met Bailão very early in her first term. Connelly didn’t know her at all, didn’t even live in her ward. The first thing Bailão told her was that she felt the federal and provincial governments were responsible for creating new housing. Connelly agreed, but said that there were things the city could be doing as well. Bailão grabbed a pad and started taking detailed notes. “She took me seriously,” Connelly remembered, still impressed. “She listened. She wasn’t reactive, like you’re on the opposite side of me. It was ‘What have you got to say? What do we have in common?’” A few months later, when Ford wanted to sell off almost 800 homes and rooming houses owned by Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) to private investors, Bailão intervened. Advised by Connelly and others, she proposed a compromise to Ford: sell 56 vacant homes right away, and spare the remaining 600 while she established a working group to study the best options for them. Ford agreed. A decade later, with Bailão now Deputy Mayor, those same homes were finally transferred to the Neighbourhood Land Trust and the Circle Land Trust, non-profits who will maintain the dwellings as affordable housing in perpetuity. “She stepped up,” Connelly said, “in a big way.”

During Ford’s term, Bailão, who was considered centre-left, developed a reputation for pragmatism, working across political lines and patiently building consensus. When Tory was elected in 2014, that became even more apparent. While Tory had apparently little interest in housing himself, Bailão brought the issue to his attention time and time again. When he would defer a housing vote, she would typically bring it back, sometimes for multiple meetings over several years. “She had a clear understanding of the politics,” said Alan Broadbent, the founder and chair of the Maytree Foundation. “When to kind of water the wine, when to take a step back, when not to force a vote because it might close the door forever. Not always happy with having to do that, but also understanding that there’s a real world you have to deal with with this stuff.”

By Tory’s second term, affordable housing—which, admittedly, had grown into an urgent issue everywhere—had become a priority for the government. Over the course of that term, Bailão accomplished a considerable amount. She recognized that job number one was to preserve the affordable housing that the city already had. To that end, she helped develop the Multi-Unit Residential Acquisition program, which helps non-profits remove private units from the market and turn them into permanent affordable rental homes. She managed to put TCHC on firm financial footing, and helped secure $1.3-billion in funding from the feds to help renovate TCHC buildings.

One of Bailão’s signature initiatives was CreateTO, an agency tasked with building affordable rental units on city-owned lands. The agency’s program, Housing Now, started in December 2018, and twenty-one sites were selected for phase one. As of this writing, however, the city still has not broken ground on any of these projects, attributing the delay to the pandemic, rising interest rates, and increased construction costs.

A month after Housing Now’s inception, a citizen watchdog group called HousingNowTO began to monitor this lack of progress. It built a regularly updated, publicly accessible map of the sites, and made frequent deputations to council on the program’s shortcomings. But Mark Richardson, the group’s volunteer senior technical lead and its public face, nevertheless felt that delays had less to do with Bailão than with Tory and suburban councillors like Denzil Minnan-Wong and Stephen Holyday, who were either hostile or indifferent to the program. “It’s not like she was an untethered agent,” Richardson said. “But of all the deputy mayors, she was the only one all-in for affordable housing.” He pointed out that when the city launched its rapid modular supportive housing program, she absorbed the NIMBY pain—one of the first such buildings to open was in her ward. When, in the fall of 2021, she voted to defer the expansion of rooming houses, Richardson argued, she did so because she knew the motion would otherwise die and she wanted it to come back during that council term. “She’s a problem solver,” he said, “who knows how to unstick things at City Hall when they get a little bit stuck.”

Over two terms on council, Bailão was, from the public’s perspective, elusive. In an era of chest-thumping, egoic male politicians like the Fords and Trump (and even Tory, in his officious way), her brand of modest, strategic governance rarely registered—for better or worse.

For all of Bailão’s accomplishments on housing, over two terms on council, she was, from the public’s perspective, elusive. In an era of chest-thumping, egoic male politicians like the Fords and Trump (and even Tory, in his officious way), her brand of modest, strategic governance rarely registered—for better or worse. When I first started researching this story, and though I’ve lived in her ward for many years, I knew little about her. While she certainly was an improvement over Cesar Palacio, the councillor she replaced after Doug Ford cut Toronto’s wards in half in 2018 and Palacio withdrew from the election, the bar that Palacio set was embarrassingly low. I never saw her, had no contact with her or her office, had no sense of her as a person or even as a politician. I had only the vaguest awareness of her work on housing. By the end of her last term, I could only confidently say that I knew two things about Bailão really—that it took her about three years to get a badly needed traffic light installed near our house and that, during her first term, she was arrested for drunk driving after an evening spent with casino lobbyists.

And yet, like a lot of so-called progressives, I still had the impression that she was a Tory toady, as preoccupied with power as he seemed to be. Her council voting record suggested as much. She voted with Tory 87.5 percent of the time, and almost 100 percent in her last term. She voted down attempts to raise residential property taxes or reduce the police budget, even when her constituents asked her to. She appeared to be too cozy with developers, having taken a job with one when she left office, and now her campaign office was even in a building owned by that developer. She hired Nick Kouvalis, the much-reviled campaign strategist who had helped elect Doug Ford and Tory, to be her pollster. When she began to unveil her platform, promising to repair crippled services and close the city’s enormous budget gap, a number of people pointed out that it was her very government that led to those problems in the first place. As soon as the campaign began, an anonymous account called BailãoBrokeIt popped up on Twitter. When I told a friend of mine that I was writing this profile, she threw up her hands and snapped, “I can’t even with Ana Bailão.”

One person’s right-wing functionary is another’s left-wing kook. On Twitter—small sample size, granted—former Sun columnist Sue-Ann Levy opined that Bailão was a “complete puppet for the unions” while individual members of LiUNA and CUPE complained that their leaders were endorsing her. (Five labour unions have now endorsed Bailão, as have sitting councillors like Shelley Carroll, Paul Ainslie, and Chris Moise, as well as former mayors Art Eggleton and Barbara Hall.)

But the Bailão I first met in late March was neither functionary nor kook. We met at Café Paradise at Bloor and Dovercourt, a stone’s throw from the modest semi she shares with her 12-year-old Maltese poodle, Minda. She wore glasses with heavy black frames, an electric-blue blazer, and a toothy, hopeful smile. Officially, the campaign was still a few days away, but she was already in election mode. Her Twitter feed was a steady stream of commemorations—of Nowruz, of Ramadan, of Trans Day of Visibility—and teasing glimpses of her platform: promises to finally bring cell phone service to the TTC, and to upload the Gardiner/DVP to the province. At that moment, her living room was serving as her campaign office, and it was just her, her comms person Blue Knox, and a handful of volunteers.

We spoke for about half an hour. She was cordial, wonkish, understated. Still, after all these years, slightly concerned that she might say the wrong thing, she stuck to her script. At that point anyway, she was hesitant to discuss much of her platform beyond saying that she wouldn’t raise property taxes above the rate of inflation. Instead, as she had done publicly already, and would do frequently throughout the campaign, she insisted that she would get the federal and provincial governments to cough up a lot more money for Toronto. Her argument was familiar—Toronto’s the economic engine of the country, it contributes a lot more in tax revenue than other places, and it disproportionately bears the cost of infrastructure that other regions use. It absolutely needs other levels of government to invest in it. “What we need is not a cheque at the end of the year,” she said. “What we need is a fair deal. What they need to understand is there’s a lot on our books that’s the responsibility of the province and the feds.”

It was a drum that many previous Toronto mayors, including Tory, have beaten, with little to show for it. The province had already said it wouldn’t upload the Gardiner. How would Bailão do it? She didn’t strike me as an especially persuasive, seductive, or tough-nosed negotiator. Did she have a better relationship with Justin Trudeau or Doug Ford than Tory? Bailão didn’t really answer that question, but she did tell me the same story about the TCHC scattered homes that Joy Connelly told me, where she talked Rob Ford out of his plan and eventually got Trudeau to cover the costs. “I’ve done it before,” she said.

We had similar conversations in our next few meetings, where she was resolutely on-message. I wasn’t completely convinced, but as I spoke with more housing experts, a more compelling and complex figure began to emerge. Then, out canvassing with her one mild spring evening, I saw a much different Bailão. Granted, we were more or less in her backyard, doing the blocks immediately east of her house, but she displayed an ease, joy, and warmth I hadn’t yet seen. Wearing a charcoal grey pantsuit and the most sensible footwear imaginable—a cross between a tasselled, taupe golf shoe and something orthopedic—she bobbed through the neighbourhood, making small talk in Portuguese to aged homeowners and, at one door, happily getting into the weeds on the subject of short-term rentals. People in passing cars yelled out their support, others introduced her to their puppies. Early in the door-knocking, a woman named Gurbeen Bhasin showed up. Bhasin is the founder and executive director of Aangen, a not-for-profit social enterprise focused on food security and equal opportunity employment. When Bailão was a councillor, she helped Aangen fund and build a kitchen from which they produce dehydrated meals that they now sell. Bailão put her arm around Bhasin, and they walked and talked in low tones for a few blocks.

She was in top form. Her familiarity with the community, her comfort in and understanding of it, were obvious. “This is the part I really like,” she said of the canvassing. “It energizes me.” It was the kind of bland, self-flattering line a million politicians have uttered a million times. But, following her around for an hour, I found myself believing it. Or at least believing that she believed it.

Years ago, to remind herself of the importance of emotional balance, Bailão got a tattoo on the inside of her left wrist. It looks like a stylized infinity symbol, like the number 8 lying on its side. To my mind, it didn’t evoke balance as much as it did other things: limitlessness, perhaps, or the ouroboros, a snake eating its tail. At the risk of reading too much into it—a tattoo is just a tattoo—it made me think of the unending amount of work of being a mayor, the ceaseless headaches and responsibilities. Whoever inherits the city now will have their hands more than full. A decade of conservative rule, and a stubborn pandemic, has left the city in shambles. Toronto’s broke, it’s grubby, it’s unaffordable for too many. Middle-class families flee because they can’t buy a home. Refugees arrive here, seeking a better life, and end up in shelters. It feels harder to live in than any time in the 35 years I’ve lived here. Why would anyone want to be mayor?

For Bailão, not surprisingly, it comes back to her origin story. Toronto no longer feels like the safe, prosperous place where her parents were able to build a new life. “It’s challenging,” she said. “People are struggling to pay bills, they don’t feel safe.” But she insists that, as mayor, she’ll be able to restore that sense of opportunity she felt as a girl. It’s, again, a quixotic belief. But the needle she moved on housing continues to move. In early May, council approved multiplexes across the city, a long-overdue relaxation of zoning rules. It also signed on to the provincial plan to build 285,000 homes within the next decade.

“I’m the first to say that we need to do more,” she said. And, over the next several weeks, she would promise exactly that. Every few days, even as the number of people running in this election similarly multiplied, she announced new plans and ideas. Some were good (expanding BikeShare, creating a neighbourhood preventative care program for seniors), some less so (re-locating the Science Centre). When she announced her housing platform, she said she would replicate the Dufferin Grove pilot project across the city, spending $5 million on it. On paper, it sounded good. But her critics sniped again—to what end? The number of unhoused people in the city was growing exponentially and waiting lists for affordable housing remained unchanged. And what would that money be spent on? More corporate security for parks? “If the shortcomings of the Dufferin Grove Pilot Project aren’t a part of its analysis,” ESN-Parkdale’s Pabani told me, “politicians like Ana Bailão are free to use it to bolster their political capital.”

This raised the obvious and unanswerable question of her candidacy in general. Untethered from Tory, what would a Mayor Bailão look like exactly? Her experience—as a woman, as a working-class immigrant—is far different from his. She’s less an ideologue. She will have the “strong mayor” powers that he didn’t get much opportunity to use. But was all that enough? Towards the end of our last conversation, I asked if there were any votes she made on council that she regretted, any decisions she would have made differently. Things like not cutting the police budget, or her vote against declaring homelessness a municipal emergency. She paused for just a moment, and her voice sharpened. “I came to council to get things done,” she said. “When I started, I couldn’t get a headline on affordable housing. We brought the city back into the housing business. And it’s getting results. For me, it’s always about getting results.”

One person’s backroom deal is another person’s realpolitik. While this election has, at least on one level, been all about bold change, Toronto is also a more conservative place than progressives like to think. All polls indicate that if Tory were to somehow run again in June, he’d win another landslide. The electorate hasn’t quite given up on him, or his people. This hasn’t been lost on Bailão or her handlers. In late May, she posed for pictures with Tory at a basketball tournament at Filipino Centre Toronto. Dressed in a black Raptors windbreaker, Tory looked like he’d aged considerably since leaving office. Bailão, for her part, grinned broadly. If she felt any strain from threading a very tiny needle—snatching some reflected glory while also trying to slip the former mayor’s shadow—she was doing an excellent job of hiding it.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Joy Connelly is the current president of the Circle Land Trust. She is a founding board member.