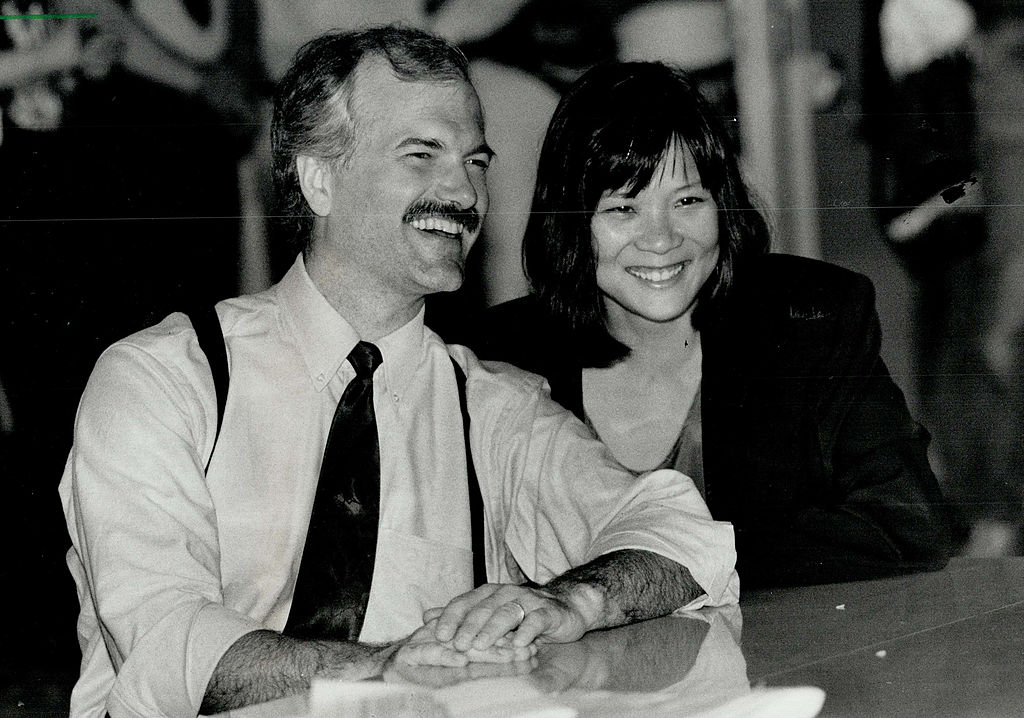

The last time Olivia Chow ran for mayor, it ended badly. In 2014, at the tail end of the extended Rob Ford fever dream—the crack tape and “more than enough to eat at home,” stripping him of his powers and the sudden cancer diagnosis—Chow had positioned herself as the sensible, obvious, inevitable person to replace him. But after months as the frontrunner, warning off other potential candidates from the left, her poll numbers plummeted. Doug Ford joined the race in place of his brother. John Tory brought a big map of his dubious transit plan across the city, along with a convincing pitch that he was the sensible, obvious anti-Ford candidate. The lasting image of the campaign was of a diminutive Chow being shouted over by two large men in navy suits. By the time it was all over, as the former NDP MP delivered a defiantly optimistic concession speech invoking her late husband Jack Layton’s call for hope over fear, she had finished a distant, disastrous third.

What politicians do at the moment they are no longer politicians is telling. When powerful, connected people find themselves on the job market, opportunities present themselves. They join law firms, latch onto foundations, are given fancy titles at important-sounding institutions. There are comfy perches at universities to be had, and Chow took one of those at Ryerson (now Toronto Metropolitan University) as a visiting professor. But in the aftermath of 2014, what Chow decided she wanted to do was to double-down on political organizing. “I called up a guy called Marshall Ganz,” she told me.

Ganz is a long-time United Farm Workers organizer who got his start during the civil rights movement and now teaches leadership at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government—a white-haired, moustachioed union man who was instrumental in designing the grassroots Barack Obama campaign in 2008. Chow already knew Ganz’s work, but now she wanted to go deeper. “Marshall said, ‘Well, the best way to learn is through failure,’” Chow recounted. She wasn’t so sure. He told her to come do some work with him anyway. “Let me teach you how to teach.”

Never Miss a Story

Sign up to get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The training, Chow said, was transformative. Political organizing wasn’t new to her, of course. She’d begun her public life as an activist, rallying in support of the “Vietnamese boat people” in the late 1970s. As a politician, both she and Layton knew that power could be wielded from a seat in parliament, sure, but sometimes you needed public pressure from people in the streets. But something about Ganz’s systematic approach to movement building struck a nerve. And it made her think about the kind of change a coalition of people could achieve, even outside of city hall. “We didn’t win the election, [but] there are so many people that want to change Toronto, or the world,” said Chow.

In 2016, she founded the Institute for Change Leaders (ICL) out of Ryerson. It was, in her vision, a place to train grassroots progressive activists using the framework Ganz had developed, adapted to a Canadian context. And over the last six years, while John Tory has been at City Hall and Doug Ford has been at Queen’s Park, that’s where she’s been—an elder statesperson once at the centre of Canadian political life now working on the fringes of a growing collection of nascent movements. She’s trained Indigenous youth and worked with refugees trying to organize. She helped early childhood educators create a movement to demand better pay. (Chow donated her time and travelled across the province to train educators, says Lyndsay McKay, one of the organizers. “She was the first person who saw how important that mission is.”) She worked with a group of former RCMP officers who had won a class-action lawsuit revealing widespread sexual harassment and were now looking to reform the force. (“We’re just five broken cops. We didn’t know anything about lobbying or organizing,” says Janet Merlo, the representative plaintiff in the case. Today there is a bill to strengthen the RCMP watchdog at the committee stage in Parliament. “I think all of that is because of our interaction with Olivia”).

Throughout this campaign, a persistent, not-unfair question has been: who is Olivia Chow to parachute into the mayor’s race after years of doing who knows what? One senior staffer at a rival campaign referenced a scene from the TV show Succession: “I think you’re a corporate legend,” says a media executive trying to tear down an aging rival with a backhanded compliment. “What you did in the ‘90s with cable? Huge.” Yes, Chow had an impressive career, the staffer acknowledged. But if she was still referencing her accomplishments under Mel Lastman, who was mayor before the iPod was invented, the question had to be asked: what had she done for the city lately?

In a notably sharp exchange from the first mayoral debate at the The Daily Bread Food Bank, Ana Bailão went after Chow directly on her time out of government. “You’ve been building the NDP party, we’ve been building the city,” said Bailão.

“I’m sorry, the time that I’ve been not in government, I was building people up. I was training them… to become effective, to make changes,” Chow replied, before taking a shot at Bailão’s own career pivot when she left city hall. “I didn’t go and work for a private developer.”

How you feel about the validity of that answer—and how you feel about the validity of organizing in general, both as a way to make change and as a potentially useful skill to have in a mayor—probably determines a lot about how you feel about Olivia Chow this election. And with the campaign in its final days, and the polls continuing to show Chow with a commanding lead, the choices she made in her time out of government might also offer clues about the kinds of choices she’ll make if she finds herself back in.

In the theory of political organizing that Olivia Chow teaches at the ICL, power is not a thing you wield. It’s something created through relationships, when people with different but overlapping goals marshal their disparate resources towards a common purpose. And these relationships are built by sharing your “public narrative” with others—why are you doing what you’re doing, and why should I join you? The narrative is what binds. Platforms and policies are secondary.

Olivia Chow’s own public narrative is well-known. Decades of news coverage and stump speeches and a 2014 memoir have covered the bases, from her immigrant upbringing to her rise from school trustee to city councillor to MP. Her marriage to the late NDP leader Jack Layton, in particular, was the focus of endless political mythmaking. The couple bought themselves a tandem bike as a wedding gift, and the image of the two of them cycling together became a preferred metaphor for their romantic and political partnership—two people moving in the same direction, stronger together. When Layton died just months after leading the party to historic gains in 2011, Chow became something else: the country’s mourner-in-chief, a bereaved woman walking stoically behind a coffin. She’d lost her life partner and political other half. And her narrative had shifted, too. Does anyone look more helpless than a single person on a tandem bike?

In this mayoral run, however, the story Olivia Chow has been telling most often isn’t about Layton. It’s about her parents. It’s how she launched her campaign in April, out on the balcony in Chinatown, and it’s a story I’ve seen her return to countless times, in a tiny room to 30 people or on the stage at a televised debate.

Here’s the quick version: in 1970 Chow arrived as a 13-year-old from Hong Kong, and she and her family moved into a St James Town apartment. Her mother worked as a hotel maid, supporting the family with a single income. Her father, meanwhile, suffered from mental health problems. He was angry, bitter about his fate, and he regularly took his bitterness out on his wife. “One night I got a call from my mom,” Chow said during her announcement speech. “She was hysterical, she was in pain, she was crying for help. My dad hurt her really badly. And I said to my mum, ‘Get to the hospital. Do it now.’”

When her mother was released, she came to stay with Chow in her run-down apartment in Kensington Market. As Chow tells it on the campaign trail, the story becomes an illustration of a policy problem. “Because I had a basement apartment, she was able to stay with me,” she said. So there you have it: affordable housing is needed, for cases just like these, and she would be the one to make sure it was built. Or, in ICL parlance, she takes the personal story and turns it into a “story of us.”

If you listen to it, though, this is actually a strange and kind of intense story for a stump speech. It’s not a black and white morality tale about a family’s triumphant escape from a monster. It’s thornier than that. Her father was abusive, but also beloved. In that same campaign launch, she explained how she cared for him as he declined, ensuring he wasn’t evicted from his own apartment. Her mother needed help but, in Chow’s telling, her father did too.

That’s a story that doesn’t naturally fit the container of a typical political anecdote. It’s complicated, like a lot of Chow’s stories. This tendency towards grey areas and fuzzy lines—something that feels far more like a natural instinct than any kind of strategy—can sometimes look like a liability on the election trail. There is beauty to a campaign with a narrative tidy enough to fit in your hand. David Miller’s broom to sweep away corruption. Ford’s vow to “end the gravy train.” John Tory’s promise of a return to boring respectability.

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

Chow’s campaign has oft-repeated themes. Toronto is “stuck.” It needs to be more caring, safe, and affordable. Her platform has a number of policies that she believes will do that, from small changes like reversing transit cuts and keeping libraries open seven days a week, to large ones like getting the city to act as a developer for 25,000 rent-controlled homes. But it rarely feels like she’s communicating a simple, clear story about her vision for this city’s future.

In some ways, this lack of clarity is less to do with presentation than with policy. Mark Saunders’ simple answer to the question of how to prevent violence on the TTC is: he’ll hire 200 special constables and install “assist buttons” on transit. (How these buttons will actually work or what services he would cut in order to pay for more security while keeping taxes flat is where things get complicated). Olivia Chow’s answer is: she’ll expand the city’s community crisis teams and add TTC staff to stations, create new respite centres for houseless people to access critical services and, even further upstream, provide more rental protections to prevent people from being evicted in the first place.

Ana Bailão’s answer to how high she’ll raise property taxes is: not above the level of inflation. Chow’s is notably less straightforward.

She has repeatedly said any property tax increase will be “modest” and left it at that. But again and again her rivals have hammered her on the details, devoting huge chunks of their time on the debate stage to asking the same question: how high will you raise property taxes? Chow has parried and deflected, smiling as she’s counterattacked. And she’s tried to explain. Setting an arbitrary number as your tax rate and then designing the budget to match is the old, wrong way of doing things. The right order, and the way it was done before the Ford years, is to figure out what the city needs, what other levels of government can provide, and then set the rate accordingly. It was, she explained, complicated.

Whether that looks like obfuscation or honesty might depend on how you feel about Toronto’s property tax rate, which remains the lowest of any city in Ontario even as services decline. But her willingness to raise the spectre of higher taxes, and to weather endless attacks for it, is a noteworthy departure from her approach in 2014.

Then, under hired-gun campaign manager John Laschinger, Chow had stressed her penny-pinching bonafides as an immigrant who knew how to keep a tight budget. It was a strategy designed to insulate her from attacks that she was a typical NDP tax-and-spend socialist. “We had many tense discussions. How should we position Olivia?” Laschinger writes in Campaign Confessions, his political memoir. “Should we accentuate her positive or try to minimize her weaknesses? We decided to adopt a defensive posture.”

That defensiveness bled through the entire campaign. There are plenty of reasons for her defeat in 2014, but Chow’s own explanation is simple: she was too scripted, too nervous about her English, afraid and inauthentic. “I didn’t connect.”

This time around, Chow says, “I just want to say what I want to say and do what I want to do, and trust my 30 years of experience.” And throughout the campaign, from an outsider’s eye, she has looked and sounded far more like herself. One evening in early May, at a town hall in the cramped confines of the event space of the community newspaper the West End Phoenix, she arrived on a bicycle braided with plastic flowers—the same way she’s gotten around the city for years—weaving through a crush of people that had been pushed out on to Bloor Street due to yet another subway delay.

At that point in the campaign, I had not yet heard her broach the subject of property taxes. Her initial housing announcement in late April had come with a whole host of laudable programs—from more money for eviction prevention to turning market-rate apartments into community land trusts—that she said would be paid for by increasing the vacant home tax from one to three percent. It felt, on its face, like wishful thinking: a way to tell Torontonians that they could fix their city without needing to pay for it. Just days after the announcement, when the city revealed that only 2,100 homes had been declared vacant, far fewer than estimated, her campaign’s already questionable math fell apart completely.

At the West End Phoenix event, when moderator Stacy Lee Kong pressed her on how she’d fund her various programs, Chow didn’t pretend there was a magical solution. “Let me just tell you all the funding sources, because I’m about to give you another one—I’m taxing,” she said. “You’re going to raise taxes?” asked Kong. “Absolutely.”

Looking around the room and sizing up the crowd—greying women with complicated necklaces, earnest thirty-something couples, a handful of clean-cut young men who looked as if they’d stepped out of a YIMBY Facebook group—she engaged in a little economic populism. “I don’t think any of you here are going to buy a house that’s three, five, 10 million?” she said. “If you are, you’re going to pay more.” She explained her “mansion tax,” which would raise the land transfer tax for houses that sold for over $3 million. People are buying $19 million mansions in the Bridle Path, she said. “I actually looked it up—wow—they have squash courts, I’m not kidding.” And if you could afford that? “Then by god, you can pay a bit more.” When the event was over she jumped on her bike and cycled home.

A few months ago, the idea that Olivia Chow might one day be mayor of Toronto did not feel like a likely scenario. When John Tory abruptly resigned after The Toronto Star revealed an inappropriate affair with a staff member, she was as surprised as anyone. She had a trip to Europe booked for the summer. She was going canoeing on the Thomsen River in the Northwest Territories. A mayoral campaign was not in her plans.

But in the weeks following the resignation, as candidates declared themselves, no one from the NDP stepped forward. Former councillor Joe Cressy, Chow’s step-son Mike Layton’s close friend, decided against a run in order to spend time with his young family. Then Layton announced he was out for the same reason. “I was trying to persuade Mike Layton to run,” Chow explained. “So when he said no, then we started looking at ‘OK, now who can do this? And then I thought: ‘Well, I could give it a try again.” When she thought about the pros and cons, the decision became clearer. “The cons list was very short,” she said. And the pros? “I think I have some ideas that the city needs… I could actually change some lives.”

Let me say the obvious thing: it’s a little weird that a conversation between a woman and her step-son could determine the next mayor of the most populous city in the country. And the notion that someone might casually decide to give running for mayor “a try” is surely enraging to grassroots candidates who do not have the luxury of stepping into a ready-made network and political machine. But this is Chow’s reality. She’s not merely embedded in this city’s progressive establishment, she’s practically foundational. To flip through her memoir is to be confronted with a capsule history of four decades of Toronto left-wing politics. Minor characters flit through its pages—confidants, friends, campaign workers, employees—who are now recognizable as the heads of the various institutions and foundations and media organizations that make up what some might call “civil society” and what Ford Nation often referred to as “the downtown elite.”

When I asked Chow about this, she scoffed at the idea that people might feel like there’s some kind of NDP cabal making decisions behind closed doors. “Oh hogwash,” she said. You didn’t see her constantly attacking her opponents for their party ties. “I guess I could,” she said, eyes upturned in faux concentration, before listing them off. Saunders is the Ford candidate. Bailão is a Liberal with Nick Kouvalis working for her. Bradford has the Conservatives. “They all have their machines.”

Chow’s right, of course, that most major candidates have political parties behind them. And whatever progressive corner of Toronto she’s part of is not the same as the deep-pocketed establishment that has run this city for the last decade, during which Torontonians had the dubious distinction of being led at every level of government by the unreasonably confident son of a wealthy, powerful man. Chow was not born into a political network, she created one. But the power of that network—those relationships, Ganz would say—has proven to be surprisingly durable in this unexpected mayoral contest.

You could see that at play one evening in mid-May at the Toronto Pavilion, an event space at Lawrence Avenue just east of the Don Valley. No cultural festival is safe from the speechifying of mayoral hopefuls during an election season, and with a full crowd in a vote-rich corner of the city, Bangladesh Festival 2023 had attracted multiple candidates. Brad Bradford paced through the auditorium, trailed by an aide clutching “Less Talk, More Action” brochures. Mitzie Hunter appeared from somewhere mid-way through the event to give her best wishes up on stage. Mark Saunders sat in the front row, looking vaguely uncomfortable. Chow, however, was running late.

Janet Davis, a popular former city councillor in that community and a Chow supporter, waited for her outside the building, texting the campaign. “She’s five minutes away,” Davis said, glancing up from her phone.

Finally a car pulled up and Chow climbed out of the passenger seat, throwing on a pale yellow jacket, shaking hands with the organizers, hugging Davis. “Am I speaking or not?” she asked. She was speaking. One of her handlers tried to show her some talking points on a smartphone that Chow dismissed with a wave of the hand. She followed Davis through a side door and suddenly they were in the darkened hall—a confusion of dry ice and thumping music, small children in traditional dress dancing in unison while a steady stream of pyrotechnics burst from the stage.

With a broad grin, the M.C. welcomed Chow to the stage. “The very, very popular and our honorable… one of the candidates for the mayor position of Toronto, our very dear Olivia Chow!” he said. She leapt to the microphone as a pair of cameramen collecting footage for a Chow campaign commercial scrambled to get her in focus. “Good evening!” she said, to cheers from the crowd. “So wonderful to see such beauty, such culture, such art, all here!”

Afterwards, Chow circulated through the lobby, accompanied by Davis and Doly Begum, the NDP MPP for Scarborough-Southwest, beloved in this hall as the first Bangladeshi-Canadian elected to a legislative body in Canada, whose first experience door-knocking was when she volunteered on a Chow campaign for MP years ago. Chow shook hands with new supporters and hugged old friends, taking selfies and exchanging business cards.

When I found her in the crowd, I said I was surprised to see so many candidates here. “Yeah… but I think I got the support of the M.C. and the organizer,” she said. (During Saunders’ turn at the mic, the introduction had been noticeably less warm. “Today, I’m not scared to call the police,” said the M.C., seeming to giggle for a moment, before asking the former chief to say a few words.) “The M.C. didn’t even mention that Mark Saunders is running for Mayor,” Chow said, the hint of a smirk on her face.

Already that day Chow had toured Somali-owned businesses in Weston and visited an Asian night market downtown. She was averaging six events a day, a punishing schedule, but she insisted she was having fun. “I have friends everywhere, you know,” she said. After so many years in public life, there weren’t many corners of the city where she didn’t have an ally who could make some introductions, a respected community member who could vouch for her. “Having roots in the community makes a big difference.”

In the hall, Davis found her again and took her by the arm, and the two of them waded back into the crowd—more hugs, more selfies, more exchanges of business cards—as Davis provided a continuous patter: “This is Olivia… this is Olivia… one, two, three, smile!… This is Olivia.”

The last time I spoke with Chow was on a warm Friday afternoon in late May. In a pink sleeveless top and white pants, she was spritely and casual, an easy host, ushering out another reporter while I came in, popping a Fishermen’s Friend to ease the throat after hours, days, weeks of talking about herself and her city.

We sat at a table in a vast, light-filled room at OCAD. Just across McCaul Street was the Art Gallery of Ontario, its curved glass facade glinting in the sun. Chow gestured out the window. The Frank Gehry-designed extension, she explained, had been one of the last big projects she’d overseen as a city councillor in 2004. The local residents weren’t sure about the design, worried the proposed addition would overshadow Grange park behind it. “So we had weekly meetings.”

This was during an election, when she should have been out canvassing, but week after week Chow gathered angry neighbours and the AGO together to hash out their differences. And in the end, the design was changed. The exterior became a tint of blue to blend into the sky. Gehry added a squiggle of a staircase on the outside. “Through a long and involved process, I felt, a better building was created,” she writes in her memoir.

If you want to understand Chow’s governing philosophy, a lot of it’s there. While the typical right-wing attack is that Chow is some kind of radical socialist (if not a full-fledged, Chinese-government operative), the reality is less exciting. Chow is a democrat—someone who genuinely believes in bringing regular people into the political process. “She’s very much about making politics a participatory sport, not an individual spectator sport,” says Myer Siemiatycki, professor emeritus of political science and Chow’s colleague at TMU. “That’s a very distinctive quality that Olivia has, which is a focus on mobilizing, on building capacity.”

Maybe this sounds absolutely boilerplate. Has a candidate ever run on a platform of subverting the will of the people? But in Toronto in 2023, Chow’s approach feels rarer than you’d think. It’s not just Mark Saunders or Brad “strong mayor of action” Bradford who have sensed a desire among some Torontonians for a firm mayoral hand. Decades of political timidity from both left-leaning and conservative leaders—of acquiescing to the sensitivities of those who come out to public meetings over those who may never have the opportunity to make Toronto their home in the first place—have made many voters impatient. Do we need a mayor who will meet with cranky neighbours week after week because of some shadow in a park? We are in a housing crisis that demands bold, immediate action. There is a $1.5 billion hole in the budget. Among some progressives, there is a genuine appetite for a leader who will discard the frustrating work of consultation and engagement, bulldoze intransigent councillors and whiney locals, and just do what needs to be done. Not a strongman, exactly, but someone with strongman-ish tendencies, only this time just for things that I think are good.

Olivia Chow is not that person. In her 2014 memoir, she lays out what feels to me like the clearest distillation of her political ethos I’ve read, so it’s worth quoting at length:

“What Jack wanted, what I want, is an engaged society. Anything with the words ‘community-based’ in front of it is bound to be good. With engaged citizens, you get better decisions. When there is common purpose, a deadline and a good facilitator, democracy works fine. Lately I see a drift towards less participation—in part because families have less money, less time, more debt. Together, this means that there’s less time to participate. Some people in power want that, but it’s not healthy.”

This is how she works. It’s how she worked as a young school trustee when, facing fierce right-wing opposition to her push to develop an anti-homophobic curriculum and include sexual orientation in the school board’s human rights policy, she encouraged students themselves to share their stories of harassment and homophobia with the board in order to tip the vote. It was how she worked as an MP, when she collaborated with the Chinese Canadian community to push for a national apology for the racist Chinese Head Tax. It’s how she’s always operated, and eight years of Tory’s Toronto have not changed anything.

Chow has insisted she will not use the “strong mayor” powers that allow a leader to act with the support of just one-third of council; “If I can’t persuade my colleagues to buy in on an idea, then if I’m gone, it’s going to be gone, too.” She has vowed to open up the budget process to the people of Toronto; if there are fights to be had with the province and the feds over a new deal for the city, she wants to marshall the support of citizens, not just councillors. She’s promised to create a renters committee to help devise new protections against renovictions, an attempt to bring the voices of the nearly 50 percent of Torontonians who rent into a city council of homeowners. Her time at the ICL, trying to help regular people change the circumstances of the world they live in, was not a sideline from her politics—it was at the core of her work.

Chow began this campaign polling a little over 20 percent. In the months since, the gap between her and her closest rivals has only grown. Across the debates, over weeks of barbs and attacks and “Stop Chow” campaigns, she has continued to more than double her nearest competitor. Is that because Chow has been relaxed, authentic, and herself? Is it a simple question of name recognition, combined with the fact that none of the other candidates have jumped off the podium to inspire passion? That certainly has something to do with it.

But knowing a name is not enough. You have to like the person attached to it. And in an election where all the candidates, even those most closely tied to John Tory’s policies, have tried to position themselves as the person who will set Toronto on a new course, Chow’s story has been the most convincing. That’s not because of brilliant oratory or the specificity of her platform, which is less detailed than the policies of some of her progressive competitors. It’s something else—some amalgam of her history in the community, her record, and her personal journey that you might as well call her “public narrative.”

What Chow’s approach might look like in the mayor’s seat is an open question. Toronto is in a tough place: broke, in decline in ways both big and small, and suffused with levels of cynicism that feel like a difficult fit for her earnest appeals for engagement. But that’s who she is, and this election she’s just saying what she means, so that’s her pitch—that the relationships and organizing and coalition-building of a lifetime will be enough to make change in a city that has been extremely resistant to it.

At OCAD, Chow was wrapping things up, collecting her things into the small white knapsack she’s dragged from place to place this election season. She was on her way up to Thorncliffe Park, then Flemingdon, to meet more people, to keep having the conversations that she insists are at the heart of not just electioneering but governing too. Real change, structural change, she said, can’t be achieved with a big mayoral announcement or proclamation. It needs to be embedded in the city, entrenched so deep that nothing can pull it out. “And that can only be done through a lot of relationship building.”

Correction: an earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that Olivia Chow does not have a driver’s license.