In the 1980s, when he was a child, Josh Matlow spent his time as many did, playing with plasticine. But while other kids created little Play-Doh figurines or spaceships from Star Wars, Matlow spent countless hours fastidiously working on what he called “Chronic”: a detailed plasticine city replete with streets, houses, neighbourhoods mapped out on graph paper, and skyscrapers with windows poked out with a pin.

“It was really a piece of art, like, it took up a whole coffee table,” says his sibling Rachel Matlow. “He knew each building, who lived in each house, and each neighbourhood. He had this whole city, and he just spent hours and hours building and playing with it on his own.”

It is, as metaphors go, almost too on the nose. The young Josh Matlow was fascinated by the layout and organization of cities. Now, in 2023, he’s running to be mayor of the largest city in the country.

New Candidate Profiles Each Week

Sign up to get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

The image of Matlow furiously working on a model city not only speaks to a fascination with the urban, it also betrays a charming sort of earnestness. And in person, Matlow is earnest, and convivial and personable, too. What is unusual about him as a public figure, though, is that, whatever idealized, abstract image of the city Matlow toyed with as a child, his vision of what a city should be has changed substantially. During the two decades he has been in public service, first as a school board trustee, then a city councillor since 2010, Matlow’s politics have taken a sharp turn. In years past, his centrism was so resolute that it was often seen as extreme. More recently, however, and as he runs for mayor today, he has consistently and energetically made decisions and announcements that are inarguably progressive.

On the campaign trail and in interviews, he has talked about an evidence-based approach to politics, and is open about the fact that it can alienate some. He’s proposed two new housing initiatives, one of which includes a seed fund for new public housing. And he’s spoken forcefully about the need to increase revenue streams for the city, including taking the ever-risky stance of announcing that he wants to raise property taxes.

It’s a change that has won him fans, but has also produced skeptics, and even enemies. After all, cynicism is often a reasonable pose to strike when it comes to politics, and changes of heart are often seen as convenient, rather than reflections of deeply felt belief. Do politicians change? When it comes to Josh Matlow, it’s hard not to find yourself pondering strangely abstract questions. So here’s one more: when politicians do appear to change, what are we then supposed to make of them?

From a Jewish family in midtown Toronto, Matlow is the son of Teddy, a lawyer, and Elaine Mitchell, a teacher and writer. The latter is the subject of the book Dead Mom Walking, by Matlow’s non-binary sibling Rachel Matlow. Fascinating in its own right, the book is primarily an account of Rachel’s relationship with a mother who, when diagnosed with colon cancer, refuses treatment. But it also provides glimpses of Josh as an adolescent, an outsider who never quite fit in.

“Coming from Cedarvale, which is pretty closed, and middle-class or upper-middle-class, I think, we both never really felt we belonged in that culture,” says Rachel Matlow over the phone. “We had a more unconventional mother, I guess, and maybe that helped encourage our wanting to explore the world.”

Rachel describes Josh as a wild, unhappy teenager who dropped out of high school and then travelled, including ending up at, of all things, a Sufi commune in, of all places, Albany, New York. Josh Matlow describes his pre-political life as that of a struggling actor who studied improv and went to École Jacques Lecoq, a theatre school in Paris that happens to be one the world’s premier clown schools.

His entrance into politics came in the early 2000s. While Matlow was co-director of environmental group Earthroots, the Liberal party of Ontario approached him to run as a sort of sacrificial lamb against Progressive Conservative leader Ernie Eves. Surprising exactly nobody, Eves won and became Premier. But Matlow unexpectedly only lost by a few thousand votes, and was intrigued by the experience.

“I began thinking to myself: I don’t have to knock at the door of power, I can be in there,” he says. “While I didn’t win that election, it exposed me to the idea that I could actually be a model of the kind of politics that I believe in: objective, evidence-based, not transactional, that you don’t do it to win, but just to do the right thing.“

He ran to become a TDSB trustee, and won in 2003 and again in 2006. After winning the race to represent St. Paul’s as a councillor in 2010, Matlow took pains to declare himself a centrist. “There is no one perspective that is completely more virtuous than the other,” he explained on a 2011 segment of his radio program The City with Josh Matlow, which aired on Newstalk 1010. Instead, he said, he put “good governance and evidence before anything else.”

So committed was Matlow to the idea of balanced centrism that it became the subject of mockery. A parody Twitter account active in 2011 called @NotJoshMatlow mercilessly made fun of Matlow’s centrism (example: “On the plus side, having the fifth lane on Jarvis means I can be middle of the road as I go home). It was cruel in the way that Twitter politics can be, especially in Toronto, but it also poked at something real.

As former councillor Janet Davis put it while confronting Matlow in the same episode of his radio program: “You’re branding yourself as much to your benefit to try and create the belief that there are those out there who are ideologically driven and then there’s you, in the middle, who votes purely on the merit of ‘thoughtful debate.’”

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

Matlow can sometimes inspire this sort of ire. According to insiders I spoke with, he is unpopular at city hall, an observation supported by a notable lack of endorsements from his fellow councillors.

“I would not say that he is one of the more popular councillors, amongst his peers,” says city politics watcher and Toronto Star columnist Matt Elliott. “If you talk to other councillors, they will lay that out, or at least hint at that.”

This seems to be bipartisan. His rejection of central elements of John Tory’s platform (SmartTrack, the Scarborough subway), means he has few friends on the right. And whatever his politics now, his early centrism has certainly alienated some on the left.

Yet, Elliott also suggests that while many politicians enter the field with a specific view and stick to it, what is unusual about Matlow is how his politics appear to have shifted.

“Matlow has changed a lot from those early days when he was doing his ‘truth is in the middle’ stuff,” says Elliott. “Now he’s become way more well known for sticking his flag in the ground and saying ‘This is my position on this issue, and I am going to fight for it.”

“It’s why he’s interesting,” Elliott says. “I just find it to be a fascinating political turn to make for somebody in public life.”

Political reputations are made of concrete: they are formed while in a fluid state, but once they are set, they are set, changeable only by something radical like a wholesale demolition.

On a weekday afternoon in early May, Josh Matlow was on the phone, pacing back and forth at the entrance of his campaign office on Yonge Street near Wellesley station. Once a retail shop, the space was now mostly empty: a table up front had a box of Tim Hortons cookies and some campaign literature to greet visitors, while the rest of the room was bare.

When I entered, Matlow nodded hello, AirPods in, and then returned his attention to the call. He was speaking with Brian Gorrell, a man in Matlow’s ward who had spent 10 years and $20,000 of his own money to build a garden oasis at a Toronto Community Housing site near Mount Pleasant and Eglinton. It had become a little sea of green and colour for locals, and a refuge for Gorrell, especially after he was diagnosed with cancer. Then, without warning, TCHC razed the garden in February, citing concerns about fire hazards. Now Matlow was trying to reassure the man that he would help solve the problem—which he did, a week later, when he put forward a member’s motion to take $50,000 in funds sourced from a nearby development and put it aside as a grant for a new garden.

It was the kind of thing that almost felt like it was staged: here was Matlow, man of the people, responding to an obvious case of government overreach and callousness with a promise to make things right, just as I sauntered in.

It was a clear example of why, whatever political insiders think of him, Matlow is extremely popular as a politician. Though he quite clearly loathed the late Rob Ford, he shares his proclivity for retail politics, responding to constituents’ complaints about roads or civic disrepair. He has been elected and re-elected as city councillor handily each time he has run. In the most recent 2022 election, he had the highest margin of victory of any councillor running. While not a perfect measure, it’s a clear sign of just how well-liked he is in his own ward.

At his campaign headquarters, dressed in jeans, a button-down shirt, and a brown leather jacket, Matlow exudes an amiable warmth. His tendency to share personal details—that in part he is running because he wants his daughter to be proud of him, or that he didn’t run for mayor before because he had yet to secure care for his father, who has Alzheimer’s—seem to emerge out of something genuine, rather than a cynical desire to humanize himself. When he speaks, he makes eye contact and makes firm hand gestures, and he possesses whatever quality it is that makes you feel as if you are being listened to.

For his part, Matlow is quite clear about the cause of the change that others have noted: he has simply grown up and become more confident.

“In the earlier chapter of my career, I think I did try to please more people,” he says. “I was worried about not being liked, or I thought that compromise was the ‘best way to the yes.’”

“But I think as I found more clarity, my conviction, but also comfort within my own skin, I also decided… just screw it,” he says. “You don’t need to please everyone. In fact, you can earn people’s trust and respect more when you actually are just authentically like exactly where you’re at and what you believe.”

The proposals in Matlow’s mayoral platform are clearly a far cry from the “mushy middle” of the early 2010s. Promising to raise property taxes is something that even progressive politicians avoid during an election. Tearing down the Gardiner to put that money into housing is bold, and likely to conjure paroxysms of rage on, say, the opinion page of The Toronto Sun.

Matlow has also made commitments to restoring transit service to pre-pandemic levels, and increasing investments in the arts (there is no specific mention of clown schools). He makes it a point to adopt an adversarial tone with the province, insisting he will resist the Ford government’s plans for a spa at Ontario Place. You can’t see into someone’s heart to see who they really are, but you can go to their website, and by that measure, Matlow is arguably the most progressive major candidate on the ballot.

If Matlow’s turn to progressivism is viewed suspiciously by some, it is one mostly supported by his recent voting record. There are important exceptions, though. For years, Matlow voted with John Tory not to raise property taxes. And as Colleen Bailey from housing advocacy group More Neighbours suggested to me, Matlow would often spend time as a councillor responding to citizen concerns about developments being too tall or too much.

Matlow’s sense of himself as an outsider as a child appears to have remained into adulthood. Just as former mayor David Miller could often be seen as an arrogant technocrat, Matlow’s approach can sometimes be to run roughshod over protocol. Just recently, he was censured by council and docked pay for tweets about Toronto park bathrooms. Matlow tweeted that staff were lying about all bathrooms being open. It’s not that he was wrong, exactly. Rather, it was that there is a way things are done at city hall—slow, methodical—that Matlow sometimes overlooks in favour of a tweet or news soundbite.

It’s a quality that can rub a lot of people the wrong way.

“A lot of the work of council is having some informal conversations with some of your colleagues, working with staff to try to get some reports written that then helps you make your case,” says Matt Elliott.

“And I think there’s this feeling that sometimes Matlow sort of jumps right to the ‘I’m going to go to the press and get the newspaper headline’,” he says. “He calls for pretty significant change instead of going through the process that would be more conducive to, you know, actually winning.”

But part of being a politician, especially one who leads, is to draw attention to things. Bruce Davis, the president of the affordable housing consultancy Public Progress, was a TDSB trustee at the same time as Matlow, and has known him for nearly 20 years.

“He always had the ability to get attention for things that he was working on,” says Davis. “He has a real knack for being able to grab something and turn it into news.”

According to Davis, it’s a quality that reflects Matlow’s newfound sense of himself as a leader and a contender.

“He’s not Leader of the Opposition anymore,” says Davis of Matlow’s reputation for dogging former mayor John Tory. “Now I’m really seeing him pivot to prospective mayor, which is kind of cool.”

In that sense, Matlow is something of a contradiction. Initially a people-pleaser, he has since decided to take a stand on particular issues and take what some might see as a principle-based approach to politics, an approach that is clearly winning him respect in some circles.

A particularly strident stand, though, can also be a problem when it is contradicted by the past; when one is adamant about something today that one was sure about in a different way some years ago, it can be hard for even sympathetic onlookers to distinguish between a genuine change of heart and a convenient u-turn.

“I don’t think he’s a weathervane, exactly,” said one longtime political commentator. “But I do think he has spent the last decade or so trying to be sure he’s moving with the tide of contemporary politics so that when his time came he wouldn’t be at the margins.”

An uncomfortable example might be around race, particularly in changing proposals put forth by Black activists. As a school trustee in the late 2000s, Matlow was firmly opposed to the pilot Africentric school, essentially implying that it was segregation. In 2016, he opposed Michael Thompson’s proposal to freeze the police budget. Then in 2020, in contrast, Matlow proposed defunding the police budget by 10 percent to put that money toward public supports.

Matlow certainly wouldn’t be alone, especially among white progressives, in having changed his view of policing post-George Floyd and the BLM surge of 2020. The motion he and then-councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam put forward in 2020 asserts that Toronto, its budget, and its police service are steeped in systemic racism and that anti-Black racism is real and pervasive.

It’s one of those things that you might read differently depending on how much you believe change is real or sincere. In one’s personal life, giving someone the benefit of the doubt can be healthy. But in politics, it is often seen as a sign of naïvetée—that politicians’ real plans are hidden things only revealed through careful scrutiny of coded messages and past behaviour.

What is less clear is how much change even matters to an electorate. Political reputations are made of concrete: they are formed while in a fluid state, but once they are set, they are set, changeable only by something radical like a wholesale demolition. In part, this is because politicians aren’t merely people but representations or avatars of ideas; changing our idea of them means changing how we identify them, and by extension, the horizon of public life.

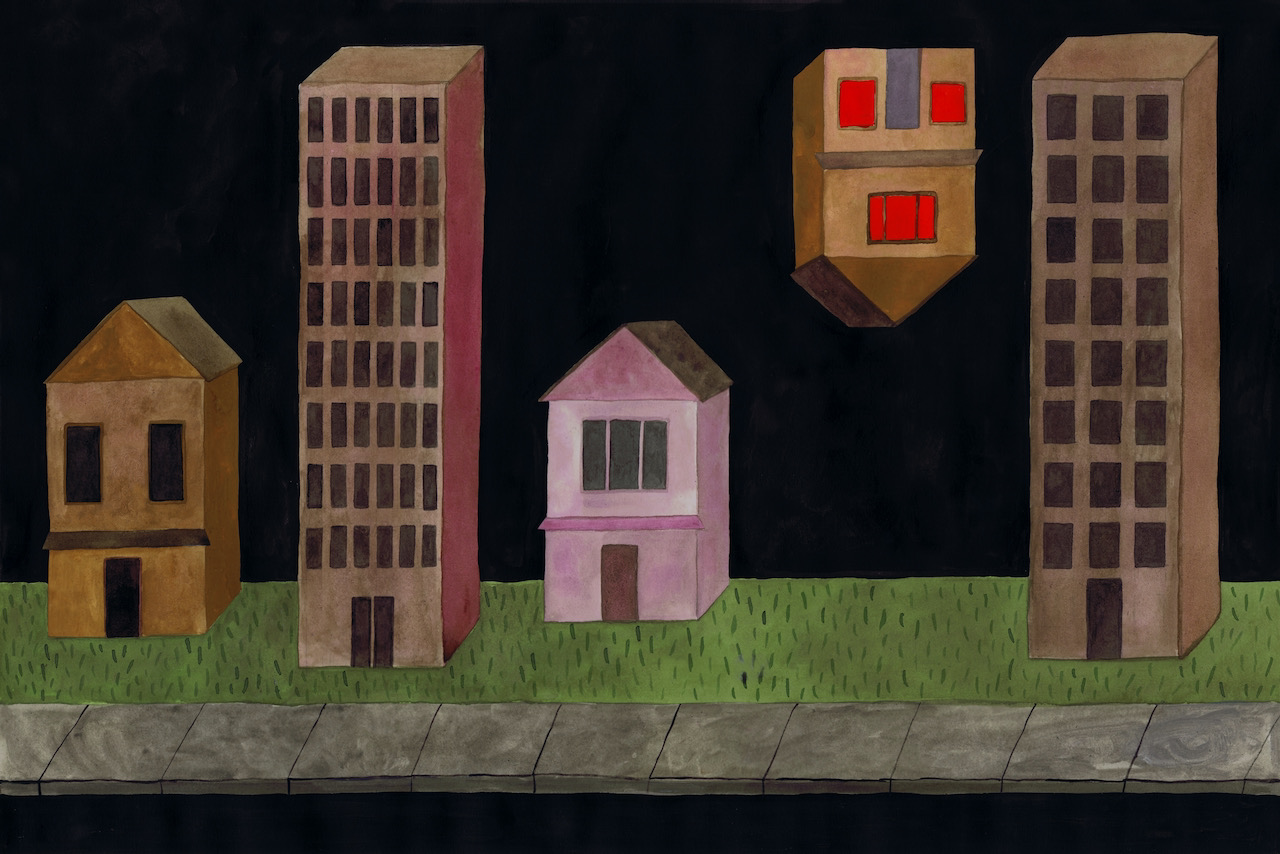

When we try to read politicians we are doing a few things at once: evaluating, looking for consistency, but all so we can comfortably either reject or embrace them. Matlow, though, often resists that simple identification because he is multiple things at once: a retail politician and ideas guy; a councillor who would nitpick condo heights, but now calls for a much more robust housing strategy; a former centrist turned ardent progressive.

It’s a mix that long-time city watcher Shawn Micallef thinks puts Matlow in a tough spot. “Matlow is actually presenting the most robust and compelling progressive vision for Toronto, but he’s not the right kind of progressive for Toronto’s left,” says Micallef. “He’s not the right kind of progressive for Toronto’s left, NDP-heavy, establishment who are arguably as status quo as the centre- and right-wing.”

Change is always hard, but it can feel especially hard in Toronto. As but one example, despite it being common practice in places like Paris and London, this year Toronto somehow yet again kicked the can down the road on allowing drinking in parks—a move that Matlow has proposed in more than one motion over the years. He, quite rightly, called the latest postponement silly. Living in Toronto, particularly when one has had the chance to visit other major cities, can feel a little dispiriting, because even small and obvious change can seem impossible.

It’s something I always swore I would ask a politician about if given the chance, so I asked Matlow: why is living in Toronto often so demoralizing?

In response, Matlow spoke honestly about the city’s failings.

“There is an insecurity that some Torontonians feel about the city,” he says. “We should be able to say the words ‘world class’ without rolling our eyes. But we aren’t protecting our most vulnerable. Some of our architecture, and certainly our public space, reaches for the height of mediocrity. We can do so much better.”

For a politician, it’s an unusually blunt take on Toronto, refreshing after years of John Tory’s anodyne boosterism. Yet Matlow also goes on to extoll the city’s virtues in a way that wouldn’t be out of place in a campaign speech.

“I’ve had a very unique experience where I’ve been meeting with communities throughout the city. I’ve been exposed to traditions and customs and cultures and aspirations and hopes and ideas and creative proposals and individuals who are inspiring,” he says. “I can tell you, we have something so special here. And it’s worth fighting for.”

When a politician says something like this, what is it you are supposed to feel? We aren’t quite sure because there is always an implied distance between what a public figure says and what we believe they really mean. As with many things about Josh Matlow, you could be forgiven for being a little skeptical. But it would also be reasonable to just assume he means it, and that alone is something. After all, to accept it as genuine you’d have to accept that people, politicians, maybe even cities, can in fact change.