Once upon a time, half a century ago, Canadian governments spent money to build, establish, and operate affordable housing projects. They also gave housing co-ops and non-profits financing and subsidies to do the same. However, this approach fell out of fashion. Partly, it was expensive—but in the political and economic climate of the 80s and 90s, the prevailing mindset was that a government’s priority should be to facilitate a free market, not to operate social programs themselves. So governments began getting out of the housing business.

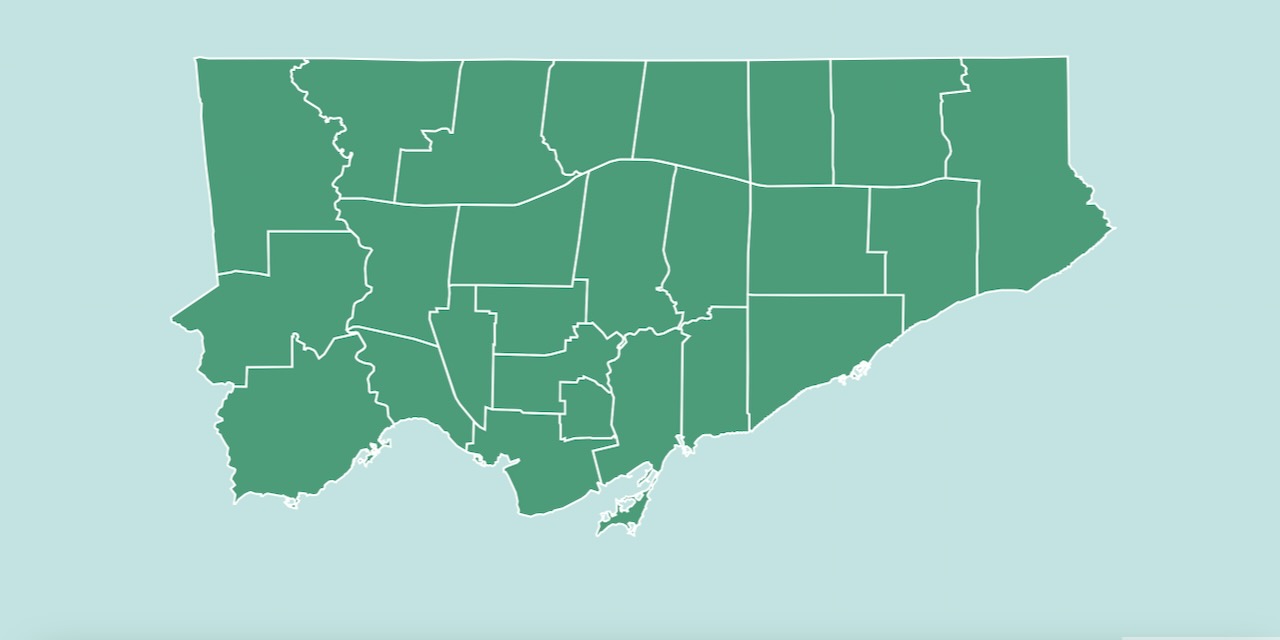

First, the federal government handed down its housing to the provincial government; then the province passed it off to the city. By the 1990s, Toronto was left with a lot of housing stock that was by now rather old, expensive to maintain, and difficult to run, but still very much in demand. They partnered with non-profits and community groups and employed various strategies to make more affordable housing, all the while asking the federal and provincial governments for more money. The federal and provincial governments mostly looked very busy and pretended not to notice.

And that brings us up to the present day. At this point, everyone agrees there is a housing crisis, although not everyone agrees on exactly what the crisis is. Some point to the consistently over-capacity shelter system, the lengthy affordable housing waitlist (nearly 85,000 households, with an 8-15 year wait time), and the rise in evictions. Others emphasize skyrocketing private rents (currently averaging $2,500), the lack of new units being built, and the wide swathes of the city where, until quite recently, you could only build single-family homes rather than cheaper, denser walk-ups or mid-rises.

To make things worse, recent provincial legislation has severely restricted the city’s ability to charge developers to help recoup the cost of the infrastructure needed to serve new developments. That includes roads, sewers, parks, and community benefits like daycares and affordable housing.

Toronto’s next mayor will have to deal with all of these issues in the face of a severe budget crunch and limited co-operation (or even outright hostility) from other orders of government. To address Toronto’s housing crisis, there’s a need for creative solutions, a substantial amount of money, and—most difficult of all—a mayor with political will and perhaps even genuine courage.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

The current landscape of city-led solutions is a tangle of blandly named programs, agencies, and legislation: Housing Now, Open Door, HousingTO, Concept2Keys, and so on. Some programs are aimed at preserving existing housing and supporting residents via rent supplements, property tax rebates, retrofitting old buildings, and so on. Others are intended to add more shelter space and housing, typically in close co-operation with the non-profit sector. There are also programs and policies targeting the private housing supply—for example, creating incentives (or requirements) for affordable units in new developments, or making it easier for homeowners to add laneway or “in-law” suites.

These are all part of HousingTO, Toronto’s ten-year (2020-2030) housing strategy. The city’s key goals for the initiative include creating 40,000 new rental units, nearly half of which are supportive housing, and one in ten is an affordable ownership unit; preventing 10,000 evictions, and providing nearly as many housing allowances for households; and maintaining 2,300 non-profit housing units whose operating agreements with other orders of government have expired. The strategy also involves repairs to nearly 60,000 Toronto Community Housing units, and waiving the Municipal Land Transfer Tax for 150,000 first-time home buyers.

It’s ambitious—but things are not exactly going smoothly. Housing Now, an impressive plan to develop affordable housing on city-owned land, slowed to a crawl during negotiations over funding with the federal government. Meanwhile, the provincial government has set a target of 285,000 new homes for Toronto, but also limited the scope of inclusionary zoning and drastically restricted the City’s ability to fund infrastructure from development charges. On top of that, the federal government’s 2017 National Housing Strategy, which includes billions of dollars cities need to subsidize rental construction, has been frustratingly opaque about where the funding is being directed.

Despite all the complexities, there are some things most of this year’s mayoral by-election frontrunners agree on. Virtually everyone wants to loosen planning and zoning regulations to tackle the “missing middle”—the low- and mid-rise buildings that offer a middle ground between single-family homes and high-rises, but which aren’t allowed in much of the city. There is broad support for strengthening existing tenant support programs like the Rent Bank, and looking into new ways to prevent renovictions. Aside from these, their platforms take dramatically different stances on the housing file, from relatively hands-off approaches to completely revamping the system.

The supply-based approach

Brad Bradford and Mark Saunders

The bike-riding former urban planner-turned-councillor and the somewhat less bike-friendly former police chief are surprisingly similar when it comes to housing. Both primarily emphasize increasing housing supply by streamlining the development process, fast-tracking approvals, and cutting red tape. Saunders pledges an approval time limit of one year for new housing developments. Bradford doesn’t give a number, but promises to establish the dedicated Development and Growth Division pitched by then-mayor John Tory shortly after the 2022 election. Bradford floats the idea of replacing office buildings with residential developments; Saunders proposes turning underused commercial space into shelters and supportive housing.

Both decry the failure of Housing Now, although it is a little more awkward coming from Bradford, who—as a Tory ally and former planner—backed the program. Bradford says that if elected mayor, he would “rescue” the fizzled plan, requiring developments on underused city-owned land to make 33 percent of units affordable. Saunders’ proposal is to let non-profit addiction treatment services set up shop in underused city properties for free, in exchange for reserving a set number of spaces for people referred there by emergency services, Streets to Homes, and other city agencies.

Saunders’ vow to crack down on encampments is ominous (addiction services won’t magically house people), but he at least says more about homelessness than Bradford. On the other hand, it’s likely whatever Bradford has in mind for the “missing middle” beyond “mid-rises on avenues” is more solid than Saunders’ idea of allowing up to 20 extra units “where appropriate” per residential building, which suggests a profound unfamiliarity with city planning. Negotiating higher density on a case-by-case basis is already a routine and highly regulated part of the development process. Many new condos and apartment buildings have hundreds of units and dozens of storeys, and adding one or two floors would have a negligible effect.

But beyond any particular aspects of their housing plans, what sets Bradford and Saunders apart from the other frontrunners is their caginess about what exactly their plans will cost and how they plan to pay for it.

Staying the course

Ana Bailão

If you were hoping for an impactful and wide-ranging plan from the former councillor who spent three terms spearheading affordable housing initiatives, you’ll be disappointed. Ana Bailão’s housing plan is a surprisingly modest $48.5 million, all from what’s already in the City Building Fund, and includes little more than expanding or speeding up programs that were already part of the HousingTO ten-year plan. The initiatives are all well worth funding, including $10 million to triple the Rent Bank and $5 million to the city-wide expansion of the non-violent, service-based approach to the Dufferin Grove encampment. But overall her plan follows the trajectory the city is already on: committing minimal resources to city-operated social housing and shelters, providing tenant assistance programs and helping non-profits and co-ops to build and operate housing, and a lot of asking the provincial and federal governments for money while not attempting to make up the shortfall with residential property taxes.

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

A new agency

The next three candidates all propose using the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) Rental Construction Financing Initiative (RCFI) to build thousands of units of affordable housing on city-owned land, sustained by ongoing revenue from market-rate rental units. However, they differ considerably on how to pay for it.

None of the proposals will satisfy the city’s ten-year goal of 44,000 affordable homes, nor make a dent in the 84,000-household subsidized housing waitlist. But by getting the city back into the social housing business, they represent a genuinely new approach and are vastly more ambitious than what’s currently on the table.

Josh Matlow

Matlow’s $406.7 million housing plan would establish a social housing agency, Public Build Toronto, to develop 15,000 units, a yet-to-be-determined mix of rent-controlled market rent, affordable, and rent-geared-to-income (40 percent of average market rent) units. Matlow cites the Vienna model—publicly owned, mixed-income housing developed by non-profits—as an inspiration. His plan includes a $50 million increase for the Multi-Unit Residential Acquisition program (MURA), which provides grants to non-profits and co-ops buying up affordable housing like rooming houses. And $56.1 million is earmarked for a comprehensive homelessness plan that includes a full review of shelter standards and policies, expanding drop-ins and respite centres, and thousands of new rent supplements. There are also, of course, the obligatory “missing middle” planning and zoning changes: allowing bigger developments on major streets beyond the downtown core, fourplexes, and so on.

The catch: it would be funded with money saved by cancelling the Gardiner Expressway East rehabilitation project and freezing the police budget for three years. Revisiting the Gardiner East project has been one of Matlow’s quixotic pet causes (like his repeated attempts to cancel the Scarborough subway)—this strategy may be too controversial to win broad support.

Mitzie Hunter

Mitzie Hunter’s detailed six-year plan aims to build 22,700 units, a mix of rent-controlled market rent, affordable rental, rent-geared-to-income, and affordable ownership units. Buildings would be relatively small (10 to 20 storeys), enabling them to be put on lots that are already built-up but still have a bit of room. Like the other proposed public housing agencies, construction would be financed by CMHC’s RCFI.

The agency’s startup cost, $1 billion over 4 years, is substantial—but unlike Matlow, Hunter explicitly rules out freezing or cutting the police budget. Half would come from capital reserves, funds mostly earmarked for expensive, long-term purposes, which is financially risky but potentially worth the payoff. The other half would come from the operating budget and require a residential property tax rate increase.

By design, the residential property tax rate doesn’t reflect the value of a property—just its increase or decrease relative to the city average—nor is it proportionate to the property owner’s income, like an income tax. Hunter’s plan to get around this is clever: implement a relatively high tax increase of 6 percent, but offer a 50 percent rebate to households with an income below $80,000. The City already has a rebate program allowing seniors making under $55,000 and people on disability benefits to cancel or defer property taxes, and every year various councillors pretend it doesn’t exist in order to say that raising property taxes will drive poor seniors out of their homes.

Olivia Chow

Olivia Chow’s 8-year, $404 million plan does not technically involve establishing a new agency, but instead greatly expanding the scope of the city’s existing real estate agency, CreateTO. The end goal is 25,000 units, with a mix of market rate, affordable and rent-geared-to-income (80 and 30 percent average market rate, respectively) and a range of sizes, with 40 percent being 2–3-bedroom units. It would be funded by an 0.33 percent increase to the City Building Fund, the extra tax levy earmarked for transit and housing infrastructure; renting commercial space in the buildings; and ongoing revenue from rents. Chow also mentions taking advantage of another CMHC program, the Housing Accelerator Fund. Interestingly, she also promises that if CHMC does not agree to finance such a large-scale plan, she will commit to starting on 10,000 units anyway.

Another feature that sets Chow’s plan apart is her willingness to increase a range of taxes. She proposes beefing up implementation of the newly introduced Vacant Homes Tax, which brought in less revenue than predicted, and raising it from 1 percent to 3 percent. The revenue would be earmarked for tenant support programs, eviction prevention, and helping non-profit housing providers buy and develop affordable rental apartment buildings. Her proposed Secure Affordable Homes Fund sounds similar to the existing Multi-Unit Residential Acquisition program, and it’s not clear what the relationship between them would be.

Chow would also raise the Municipal Land Transfer Tax (MLTT) on luxury homes, starting at 3.5 percent for houses worth $3 million and up and topping out at 7.5 percent for houses worth over $20 million. While these only account for a fraction of sales, it would bring in about as much as a one percent residential property tax rate increase. About half would be allocated for rent supplements, with revenue also going to expand shelter spaces and services.

While this generates less revenue than Hunter’s strategy, it is also less risky. It’s interesting that both use the City’s limited powers to create something that is a bit like a progressive tax. If Toronto wants to build housing, the mayor and city council will have to get creative with the tools the City already has—and not bank too much on Ottawa or Queen’s Park bailing us out.

For voters who prioritize increasing the supply of market-rate housing, Bradford’s and Saunders’s “red tape”-cutting approaches will have the most appeal. For those who are more or less satisfied with the scope and pace of the city’s housing plans, Bailão’s track record makes her a reliable choice. But for those who want to revive the 70’s-era vision of large-scale purpose-built social housing—and, more importantly, are willing to pay for it—Matlow, Hunter, and Chow are promising bold ways forward.